"Κ'na" Dance: the Construction of Ethnic and National Identity in Nea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

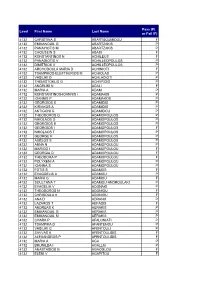

Results Level 3

Pass (P) Level First Name Last Name or Fail (F) 4132 CHRISTINA S ABARTSOUMIDOU F 4132 EMMANOUIL G ABARTZAKIS P 4132 PANAYIOTIS M ABARTZAKIS P 4132 CHOUSEIN S ABASI F 4132 KONSTANTINOS N ACHILEUS F 4132 PANAGIOTIS V ACHILLEOPOULOS P 4132 DIMITRIOS V ACHILLEOPOULOS P 4132 ARCHODOULA MARIA D ACHINIOTI F 4132 TSAMPIKOS-ELEFTHERIOS M ACHIOLAS P 4132 VASILIKI D ACHLADIOTI P 4132 THEMISTOKLIS G ACHYRIDIS P 4132 ANGELIKI N ADALI F 4132 MARIA A ADAM P 4132 KONSTANTINOS-IOANNIS I ADAMAKIS P 4132 IOANNIS P ADAMAKOS P 4132 GEORGIOS S ADAMIDIS P 4132 KIRIAKOS A ADAMIDIS P 4132 ANTIGONI G ADAMIDOU P 4132 THEODOROS G ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 NIKOLAOS G ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 GEORGIOS E ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 GEORGIOS I ADAMOPOULOS F 4132 NIKOLAOS T ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 GEORGE K ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 AGELOS S ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 ANNA N ADAMOPOULOU P 4132 MARIGO I ADAMOPOULOU F 4132 GEORGIA D ADAMOPOULOU F 4132 THEODORA P ADAMOPOULOU F 4132 POLYXENI A ADAMOPOULOU P 4132 IOANNA S ADAMOPOULOU P 4132 FOTIS S ADAMOS F 4132 EVAGGELIA A ADAMOU P 4132 MARIA G ADAMOU F 4132 SOULTANA T ADAMOU-ANDROULAKI P 4132 EVAGELIA V ADONAKI P 4132 THEODOROS N ADONIOU F 4132 CHRISOULA K ADONIOU F 4132 ANA D ADRANJI P 4132 LAZAROS T AEFADIS F 4132 ANDREAS K AERAKIS P 4132 EMMANOUIL G AERAKIS P 4132 EMMANOUIL M AERAKIS P 4132 CHARA P AFALONIATI P 4132 TSAMPIKA D AFANTENOU P 4132 VASILIKI G AFENTOULI P 4132 SAVVAS A AFENTOULIDIS F 4132 ALEXANDROS P AFENTOULIDIS F 4132 MARIA A AGA P 4132 BRUNILDA I AGALLIU P 4132 ANASTASIOS G AGAOGLOU F 4132 ELENI V AGAPITOU F 4132 JOHN K AGATHAGGELOS P 4132 PANAGIOTA -

2020/860 of 18 June 2020 Amending the Annex to Implementing

L 195/94 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union 19.6.2020 COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION (EU) 2020/860 of 18 June 2020 amending the Annex to Implementing Decision 2014/709/EU concerning animal health control measures relating to African swine fever in certain Member States (notified under document C(2020) 4177) (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Directive 89/662/EEC of 11 December 1989 concerning veterinary checks in intra-Community trade with a view to the completion of the internal market (1), and in particular Article 9(4) thereof, Having regard to Council Directive 90/425/EEC of 26 June 1990 concerning veterinary checks applicable in intra-Union trade in certain live animals and products with a view to the completion of the internal market (2), and in particular Article 10(4) thereof, Having regard to Council Directive 2002/99/EC of 16 December 2002 laying down the animal health rules governing the production, processing, distribution and introduction of products of animal origin for human consumption (3), and in particular Article 4(3) thereof, Whereas: (1) Commission Implementing Decision 2014/709/EU (4) lays down animal health control measures in relation to African swine fever in certain Member States, where there have been confirmed cases of that disease in domestic or feral pigs (the Member States concerned). The Annex to that Implementing Decision demarcates and lists certain areas of the Member States concerned in Parts I to IV thereof, differentiated by the level of risk based on the epidemiological situation as regards that disease. -

Ö 10 - 1 Royal Empress Tango English Couple I A- 5

MVFD Listing by OLD Number CD Track Dance Name Nationality Type Inst Old # 9 - 20 Canadian Breakdown USA Contra A- 3 9 - 19 Petronella USA Contra I A- 3 ö 10 - 1 Royal Empress Tango English Couple I A- 5 9 - 21 Tango Waltz, The English Couple A- 5 10 - 2 Camptown Races USA Square I A- 8 10 - 3 Old Joe Clark USA Square A- 8 10 - 3 Old Joe Clark USA Contra A- 8 10 - 4 Bonfire (Fisher's Hornpipe) Irish Couple I A- 9 10 - 5 Come Up the Backstairs (Sacketts USA Contra I A- 9 10 - 4 Fisher's Hornpipe USA Contra I A- 9 10 - 5 Sacketts's Harbour (Come Up the USA Contra I A- 9 ö 81 - 17 Aird Of Coigah (Reel of Mey) Scottish Set 4 Couple I A-10 81 - 18 Cauld Kail in Aberdeen Scottish Set 4 Couple I A-10 81 - 15 Gates of Edinburgh (8x32 Reel) S Scottish Set 4 Couple A-10 81 - 13 Hooper's Jig (8x32 Jig) SKIPS Scottish Jig A-10 81 - 16 Jessie's Hornpipe (8x32 Reel) Scottish Contra I A-10 81 - 19 Kingussie Flower (8x40 Reel) Scottish Reel A-10 81 - 14 Macphersons of Edinburgh, The ( Scottish Set 4 Couple A-10 81 - 12 Mairi's Wedding (8x40 Reel) Scottish Set 4 Couple I A-10 81 - 19 Red House Reel (Kingussie Flow Scottish Set 4 Couple I A-10 ö 81 - 17 Reel of Hey, The (8x48 Reel) Scottish Set 4 Couple I A-10 81 - 19 White Heather Jig (Kingussie Flo Scottish Set 4 Couple I A-10 10 - 7 Geudman Of Ballangigh English Contra I A-11 10 - 6 Larusse English Square I A-11 10 - 8 Yorkshire Square Eight English Square I A-11 10 - 12 Dargason English Set 4 Couple I A-12 10 - 9 Little Man in a Fix Danish Set 2 Couple I A-12 Saturday, July 29, 2000 Page 1 of 96 MVFD -

Committee of Ministers Secrétariat Du Comite Des Ministres

SECRETARIAT GENERAL SECRETARIAT OF THE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS SECRÉTARIAT DU COMITE DES MINISTRES Contact: Simon Palmer Tel: 03.88.41.26.12 Date: 15/02/2012 DH - DD(2012)173* Item reference: 1136th meeting DH (March 2012) Communication from the government of Greece in the case of M.S.S. against Belgium and Greece (Application No. 30696/09). Information made available under Rule 8.2.a of the Rules of the Committee of Ministers for the supervision of the execution of judgments and of the terms of friendly settlements. * * * Référence du point : 1136e réunion DH (mars 2012) Communication du gouvernement de la Grèce dans l'affaire M.S.S. contre Belgique et Grèce (Requête n° 30696/09) (anglais uniquement). Informations mises à disposition en vertu de la Règle 8.2.a des Règles du Comité des Ministres pour la surveillance de l’exécution des arrêts et des termes des règlements amiables. * In the application of Article 21.b of the rules of procedure of the Committee of Ministers, it is understood that distribution of documents at the request of a Representative shall be under the sole responsibility of the said Representative, without prejudice to the legal or political position of the Committee of Ministers (CM/Del/Dec(2001)772/1.4). / Dans le cadre de l'application de l'article 21.b du Règlement intérieur du Comité des Ministres, il est entendu que la distribution de documents à la demande d'un représentant se fait sous la seule responsabilité dudit représentant, sans préjuger de la position juridique ou politique du Comité des Ministres CM/Del/Dec(2001)772/1.4). -

L6 Official Journal

Official Journal L 6 of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Legislation 10 January 2020 Contents II Non-legislative acts INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS ★ Information concerning the entry into force of the Agreement between the European Community and the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Albania on certain aspects of air services . 1 ★ Information concerning the entry into force of the Agreement between the European Community and the Republic of Armenia on certain aspects of air services . 2 ★ Information concerning the entry into force of the Agreement between the European Community and the Government of the Republic of Azerbaijan on certain aspects of air services . 3 ★ Information concerning the entry into force of the Agreement between the European Community and Bosnia-Herzegovina on certain aspects of air services . 4 ★ Information concerning the entry into force of the Agreement between the European Community and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia on certain aspects of air services . 5 ★ Information concerning the entry into force of the Agreement between the European Community and the Government of Georgia on certain aspects of air services . 6 ★ Information concerning the entry into force of the Agreement between the European Community and the State of Israel on certain aspects of air services . 7 REGULATIONS ★ Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/11 of 29 October 2019 amending Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures as regards information relating to emergency health response (1) . 8 (1) Text with EEA relevance. Acts whose titles are printed in light type are those relating to day-to-day management of agricultural matters, and are generally valid for a limited period. -

The Hellenic Centre News

THE HELLENIC CENTRE NEWS MARCH 2018 ● ISSUE NO 23 THE HELLENIC COMMUNITY TRUST REGISTERED CHARITY NO 1010360 Overview of the Year 2017 Patrons HE The Archbishop of Thyateira 2017 was a rich and successful cultural year. Aiming to include rather than exclude we organised, as and Great Britain, Gregorios always, events that were varied and attracted different audiences. HE The Ambassador of Greece Mr Dimitrios Caramitsos-Tziras As we welcomed the new influx of mainland Greeks who moved to London we realised that for many of HE The High Commissioner for Cyprus them we are a home away from home. This has created more demand for events in Greek and our Mr Euripides L Evriviades responsibility to our younger friends became a priority. To date we have put on The Boy with the Blue Hair, a play in Greek performed by theatre Fournos which was followed by a variety of carnival activi- ties like the traditional gaitanaki and a Christmas workshop where they had the chance to sing kalanta Hellenic Community Trust (Greek Christmas Carols) and bake tasty kourabiedes. We were happy we gave them the chance to Council hear their mother-tongue outside of Greek school and the home and we promise to organise more Costas Kleanthous (Chairman) events like that for them. Michael Agathou Sylvia Christodoulou Haralambos J Fafalios Of course, as always, we had a diverse cultural programme of lectures, recitals and exhibitions in place Michael Iacovou with established speakers or artists. At the same time however, opportunities were given to emerging Marilen Kedros academics and young talent. -

Dick Crum (1928-2005) Dated Material Published by the Folk Dance Federation of California, South Volume 42, No

FOLK DANCE SCENE First Class Mail 4362 Coolidge Ave. U.S. POSTAGE Los Angeles CA, 90066 PAID Los Angeles, CA Permit No. 573 ORDER FORM Please enter my subscription to FOLK DANCE SCENE for one year, beginning with the next published issue. Subscription rate: $15.00/year U.S.A., $20.00/year Canada or Mexico, $25.00/year other countries. Published monthly except for June/July and December/January issues. NAME _________________________________________ ADDRESS _________________________________________ PHONE (_____)_____–________ CITY _________________________________________ STATE __________________ E-MAIL _________________________________________ ZIP __________–________ Please mail subscription orders to the Subscription Office: 19 Village Park Way Santa Monica, CA 90405 (Allow 6-8 weeks for subscription to start if order is mailed after the 10th of the month.) First Class Mail Dick Crum (1928-2005) Dated Material Published by the Folk Dance Federation of California, South Volume 42, No. 1 February 2006 Folk Dance Scene Committee Club Directory Coordinators Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 SKANDIA FOLK DANCE DUNAJ INT’L Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 Beginner’s Classes Mon 7:00-10:00 Wed 7:00-10:00 FOLK ENSEMBLE Calendar Jay Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 CABRILLO INT’L (714) 893-8888 Ted Martin FOLK DANCERS Wed 7:00-10 On the Scene Jill Michtom [email protected] (818) 368-1957 (310) 827-3618 Sparky Sotcher (714) 641-7450 Richard Duree Club Directory Steve Himel [email protected] (949) 646-7082 Tue 7:00-8:00 ANAHEIM, Community Ctr, SANTA ANA, WISEPlace, Contributing Editor Richard Duree [email protected] (714) 641-7450 (858) 459-1336 Georgina 250 E Center (Mon) 1414 N. -

Reglamento De Ejecución (Ue) 2021/811 De La Comisión

L 180/114 ES Diar io Ofi cial de la Unión Europea 21.5.2021 REGLAMENTO DE EJECUCIÓN (UE) 2021/811 DE LA COMISIÓN de 20 de mayo de 2021 que modifica el anexo I del Reglamento de Ejecución (UE) 2021/605, por el que se establecen medidas especiales de control de la peste porcina africana (Texto pertinente a efectos del EEE) LA COMISIÓN EUROPEA, Visto el Tratado de Funcionamiento de la Unión Europea, Visto el Reglamento (UE) 2016/429 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, de 9 de marzo de 2016, relativo a las enfermedades transmisibles de los animales y por el que se modifican o derogan algunos actos en materia de sanidad animal («Legislación sobre sanidad animal») (1), y en particular su artículo 71, apartado 3, Considerando lo siguiente: (1) La peste porcina africana es una enfermedad vírica infecciosa que afecta a los porcinos silvestres y en cautividad y puede tener graves repercusiones en la población animal afectada y en la rentabilidad de la ganadería, perturbando los desplazamientos de las partidas de esos animales y sus productos dentro de la Unión y las exportaciones a terceros países. (2) El Reglamento de Ejecución (UE) 2021/605 de la Comisión (2) se adoptó en el marco del Reglamento (UE) 2016/429, y en él se establecen medidas especiales de control de la peste porcina africana que los Estados miembros que figuran en su anexo I deben aplicar durante un período de tiempo limitado en las zonas restringidas enumeradas en dicho anexo. Las zonas enumeradas como zonas restringidas I, II y III en el anexo I del Reglamento de Ejecución (UE) 2021/605 se basan en la situación epidemiológica de la peste porcina africana en la Unión. -

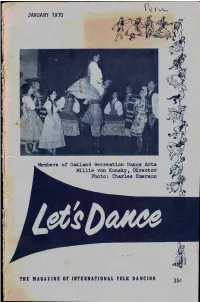

Neat Document

JANUARY 1970 Ifembers of Oakland Recreation Dance Arts Millie von Konsky, Director Photo: Charles Emerson THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL FOLK DANCING 35c >^e^ ^OHCC THE ͣ«t«Illlt OF IRTCINATIONill FOLK OilllClllt January 1970 Vol 27 - 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE FOLK DANCE FEDERATION OF CALIFORNIA, INC. Costiimes of Peru............ 1 EDITOR ........... VI Dexhelmer BUSINESS MGR ....... Walt Dexhelmer Folk Dance Popularity List,. 5 COVER DESIGN ........ Hilda Sachs Party Places................ 7 PHOTOGRAPHY ......... Henry Bloom The Party Planner.......... 11 RESEARCH COORDINATOR . Dorothy Tamburini Scottish Steps, Terms COSTUME RESEARCH EDITOR . Audrey F1field and Styling.............. l6 CONTRIBUTORS Dance Description (Scottish) Llesl Bamett Cliff Nickel! White Heather Jit........ l8 Perle Bleadon Lydia Strafelda Gall dune Fred Sweger Paris in Springtime........ 19 Al Dobrlnsky Avis Tarvin Festival Dance Program.....20 Ernest Drescher Claire Tllden Audrey Fifleld Suzy Vails In Memoriam - Dennis Evans. 29 Vera Jones Bee Whittler Echoes from the Southland.. 31 FEDERATION OFFICERS Council Clips.............. 33 (North) Calendar of Events.......38-39 PRESIDENT ........ Ernest Drescher Classified Ads............. Uo 920 Junlpera Serra, San Francisco 94132 VICE PRESIDENT........Elmer Riba TREASURER..........Leo Haimer RECORDING SECRETARY . Ferol Ann Williams DIR. of PUBLICATIONS.....Gordon Deeg DIR. of EXTENSION . .Dolly Schlwal Barnes DIR. of PUBLICITY........Ray Kane HISTORIAN..........Bee Mitchell (South) PRESIDENT .......... Avis Tarvin 314 Amalfl Dr. , Santa Monica, 90402 VICE PRESIDENT ....... Al Dobrlnsky TREASURER...........Jim Matlln RECORDING SECRETARY.....Flora Codman CORRESPONDING SECY.....Elsa Miller DIR. of EXTENSION.......Sheila Ruby DIR, of PUBLICITY.....Perle Bleadon HISTORIAN...........Bob Bowley OFFICES EDITORIAL . Advertising and Promotion VI Dexhelmer, 1604 Felton Street San Francisco, California 94134 Phone ~ 333-5583 PUBLICATION Folk Dance Federation of California, Inc. -

T.C. İstanbul Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Avrupa Birliği Anabilim Dalı

T.C. İstanbul Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Avrupa Birliği Anabilim Dalı Doktora Tezi AVRUPA BİRLİĞİ BÖLGESEL POLİTİKASI ve TÜRKİYE’NİN UYUMU -EDİRNE ÖRNEĞİ- FÜSUN ÖZERDEM 2502030053 TEZ DANIŞMANI: Prof. Dr. Hülya Baykal İstanbul-2007 ÖZ AVRUPA BİRLİĞİ BÖLGESEL POLİTİKASI ve TÜRKİYE’NİN UYUMU -EDİRNE ÖRNEĞİ- Füsun ÖZERDEM Demokrasi, iyi yönetişim ve hukukun üstünlüğü; küresel ve bölgesel güvenliğin düzenleyicileridirler. Küresel bütünleşme, ülkeler arasında siyasi, sosyal, ekonomik ilişkilerin yaygınlaşması, farklı kültür ve inançların entegre olmuş şekilde birlikte yaşamaları, maddi ve manevi değerlerin ulusal sınırları aşarak dünyaya yayılması demektir. Bu bağlamda böyle bir bütünleşmeye verilecek en güzel örnek; Avrupa Birliği’dir (AB). Kalkınma süreci yaşayan ülkelerde ekonomik gelişme, ülkenin tüm bölgelerinde aynı anda başlayamayabilir ve sonucunda ortaya çıkan gelişme belirli noktalarda yoğunlaşır. Neticesinde bölgesel farklılaşmalar meydana gelir. AB, kendi içinde yaşadığı bölgesel farklılıkları ortadan kaldırmak için AB Bölgesel Politikası’nı oluşturmuştur. Bu politika kapsamında geliştirilen Yapısal Fonlar aracılığıyla, ihtiyaç duyulan bölgelere çeşitli yardımlar yapılmakta, bu yardımlardan bazıları hibe programları ile gerçekleştirmektedir. Türkiye tam üye olmadığı için Yapısal Fonlar’dan şimdilik yararlanamamaktadır. Katılım Öncesi Mali Yardım Programı kapsamında geliştirilen hibe programlarını ise uygulayabilmektedir. Bu çerçevede bu çalışmaya örnek teşkil eden programlar; Edirne İline açık olan Bulgaristan-Türkiye -

Dance and Socio-Cybernetics: the Dance Event of “K’Na” As a Shaping Component of the Cultural Identity Amongst the Arvanites of Neo Cheimonio Evros, Greece1

Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies Copyright 2020 2020, Vol. 7, No. 2, 30-49 ISSN: 2149-1291 http://dx.doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/342 Dance and Socio-Cybernetics: The Dance event of “K’na” As A Shaping Component of The Cultural Identity Amongst the Arvanites of Neo Cheimonio Evros, Greece1 Eleni Filippidou2 and Maria Koutsouba National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Abstract: The research field of this paper is the wedding dance event of “K’na”, as this takes place by the Arvanites of Greek Thrace, an ethnic group moved to the area from Turkish Thrace in 1923. The aim of this paper is to investigate whether the three components of dance, music and song of Greek traditional dance, as these reflected in the “K’na” dance event amongst the Arvanites ethnic group of Neo Cheimonio (Evros), are related to issues of ethno-cultural identity under the lens of socio-cybernetics. Data was gathered through ethnographic method as this is applied to the study of dance, while its interpretation was based on socio-cybernetics according to Burke’s identity control theory. From the data analysis, it is showed that through the “K’na” dance event the Thracian Arvanites of Neo Cheimonio shape and reshape their ethno- cultural identity as a reaction to the input they receive from their environment. Therefore, the “construction” of their identity, as a constant process of self-regulation and internal control, is subjected to the conditions of a cybernetic process. Keywords: dance ethnography, ethnic group, identity control theory, refugees, Thrace. Introduction Identity is a concept that has come to the fore in recent years, as it has attracted the interest of many scholars. -

The Dick Crum Collection, Date (Inclusive): 1950-1985 Collection Number: 2007.01 Extent: 42 Boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2r29q890 No online items Finding Aid for the The Dick Crum Collection 1950-1985 Processed by Ethnomusicology Archive Staff. Ethnomusicology Archive UCLA 1630 Schoenberg Music Building Box 951657 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1657 Phone: (310) 825-1695 Fax: (310) 206-4738 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.ethnomusic.ucla.edu/Archive/ ©2009 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the The Dick Crum 2007.01 1 Collection 1950-1985 Descriptive Summary Title: The Dick Crum Collection, Date (inclusive): 1950-1985 Collection number: 2007.01 Extent: 42 boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Ethnomusicology Archive Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: Dick Crum (1928-2005) was a teacher, dancer, and choreographer of European folk music and dance, but his expertise was in Balkan folk culture. Over the course of his lifetime, Crum amassed thousands of European folk music records. The UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive received part of Dick Crum's personal phonograph collection in 2007. This collection consists of more than 1,300 commercially-produced phonograph recordings (LPs, 78s, 45s) primarily from Eastern Europe. Many of these albums are no longer in print, or, are difficult to purchase. More information on Dick Crum can be found in the Winter 2007 edition of the EAR (Ethnomusicology Archive Report), found here: http://www.ethnomusic.ucla.edu/archive/EARvol7no2.html#deposit. Language of Material: Collection materials in English, Croatian, Bulgarian, Serbian, Greek Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Some materials in these collections may be protected by the U.S.