A New Method of Classification for Tai Textiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

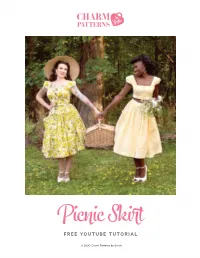

Picnic Skirt FREE YOUTUBE TUTORIAL

Picnic Skirt FREE YOUTUBE TUTORIAL © 2020 Charm Patterns by Gertie SEWING INSTRUCTIONS NOTES: This style can be made for any size child or adult, as long as you know the waist measurement, how long you want the skirt, and how full you want the skirt. I used 4 yards of width, which results in a big, full skirt with lots of gathers packed in. You can easily use a shorter yardage of fabric if you prefer fewer gathers or you’re making the skirt for a smaller person or child. Seam Finishing: all raw edges are fully enclosed in the construction process, so there is no need for seam finishing. Make a vintage-inspired button-front skirt without 5/8-inch (in) (1.5 cm) seam allowances are included on all pattern pieces, except a pattern! This cute design where otherwise noted. can be made for ANY size, from child to adult! Watch CUT YOUR SKIRT PIECES my YouTube tutorial to see 1. Cut the skirt rectangle: the width should be your desired fullness (mine is how it’s done. You can find 4 yards) plus 6 in for the doubled front overlap/facing. The length should be the coordinating top by your desired length, plus 6 in for the hem allowance, plus 5/8 in for the waist seam subscribing to our Patreon allowance. at www.patreon.com/ Length: 27 in. gertiesworld. (or your desired length) Length: + Skirt rectangle 6 in hem allowance xoxo, Gertie 27 in. Cut 1 fabric (or your + desired length) ⅝ in waist seam + Skirt rectangle 6 in hem allowance Cut 1 fabric MATERIALS + & NOTIONS ⅝ in waist seam • 4¼ yds skirt fabric (you Width: 4 yards (or your desired fullness) + 6 in for front overlap may need more or less depending on the size and Length: 27 in. -

Business Professional Dress Code

Business Professional Dress Code The way you dress can play a big role in your professional career. Part of the culture of a company is the dress code of its employees. Some companies prefer a business casual approach, while other companies require a business professional dress code. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR MEN Men should wear business suits if possible; however, blazers can be worn with dress slacks or nice khaki pants. Wearing a tie is a requirement for men in a business professional dress code. Sweaters worn with a shirt and tie are an option as well. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR WOMEN Women should wear business suits or skirt-and-blouse combinations. Women adhering to the business professional dress code can wear slacks, shirts and other formal combinations. Women dressing for a business professional dress code should try to be conservative. Revealing clothing should be avoided, and body art should be covered. Jewelry should be conservative and tasteful. COLORS AND FOOTWEAR When choosing color schemes for your business professional wardrobe, it's advisable to stay conservative. Wear "power" colors such as black, navy, dark gray and earth tones. Avoid bright colors that attract attention. Men should wear dark‐colored dress shoes. Women can wear heels or flats. Women should avoid open‐toe shoes and strapless shoes that expose the heel of the foot. GOOD HYGIENE Always practice good hygiene. For men adhering to a business professional dress code, this means good grooming habits. Facial hair should be either shaved off or well groomed. Clothing should be neat and always pressed. -

Country Profile Laos

Country profile Laos GEOGRAPHY Laos is located in southeast Asia and is approximately the same size as Victoria. It is one of the few landlocked countries in Asia with a landscape dominated by rivers and mountains. The Mekong River runs the entire length of the country and forms the national border with Thailand. The climate is tropical, with high temperature and humidity levels. The rainy season is from May to November. The tropical forests which cover much of the country are rapidly being logged. PEOPLE The official language is Lao, but French, English and other languages are also spoken. Theravada Buddhism is the dominant religion, although animist beliefs are also common, especially in the mountainous areas. The population of Laos consists of approximately 130 different ethnic groups and 80 percent of the population live in rural areas. HISTORY Laos has its origins in the ancient Lao kingdom of Lan Xang, established in the 14th century. For 300 years this kingdom Map courtesy of The General Libraries, included parts of modern-day Cambodia and Thailand, as well The University of Texas at Austin as all of what is now Laos. From the late 18th century, Laos came under the control of Siam (now Thailand) before coming under the control of France in the late 19th century. policy, but has struggled to find its position within a changing political and economic landscape. Despite tentative reforms, In 1975, communist forces ended the monarchy in Laos and Laos remains poor and dependent on international donations. ruled with a regime closely aligned to Vietnam and the Soviet It became a member of ASEAN in 1997. -

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

Language, Myth, Histories, and the Position of the Phong in Houaphan

Neither Kha, Tai, nor Lao: Language, Myth, Histories, and the Position of the Phong in Houaphan Oliver Tappe1 Nathan Badenoch2 Abstract In this paper we explore the intersections between oral and colonial history to re-examine the formation and interethnic relations in the uplands of Northern Laos. We unpack the historical and contemporary dynamics between “majority” Tai, “minority” Kha groups and the imagined cultural influence of “Lao” to draw out a more nuanced set of narratives about ethnicity, linguistic diversity, cultural contact, historical intimacy, and regional imaginings to inform our understanding of upland society. The paper brings together fieldwork and archival research, drawing on previous theoretical and areal analysis of both authors. 1. Introduction The Phong of Laos are a small group of 30,000 people with historical strongholds in the Sam Neua and Houamuang districts of Houaphan province (northeastern Laos). They stand out among the various members of the Austroasiatic language family – which encompass 33 out of the 50 ethnic groups in Laos – as one of the few completely Buddhicized groups. Unlike their animist Khmu neighbours, they have been Buddhist since precolonial times (see Bouté 2018 for the related example of the Phunoy, a Tibeto-Burman speaking group in Phongsaly Province). In contrast to the Khmu (Évrard, Stolz), Rmeet (Sprenger), Katu (Goudineau, High), Hmong (Lemoine, Tapp), Phunoy (Bouté), and other ethnic groups in Laos, the Phong still lack a thorough ethnographic study. Joachim Schliesinger (2003: 236) even called them “an obscure people”. This working paper is intended as first step towards exploring the history, language, and culture of this less known group. -

The Ethnography of Tai Yai in Yunnan

LAK CHANG A reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong LAK CHANG A reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong Yos Santasombat Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Cover: The bride (right) dressed for the first time as a married woman. Previously published by Pandanus Books National Library in Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Santasombat, Yos. Lak Chang : a reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong. Author: Yos Santasombat. Title: Lak chang : a reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong / Yos Santasombat. ISBN: 9781921536380 (pbk.) 9781921536397 (pdf) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Tai (Southeast Asian people)--China--Yunnan Province. Other Authors/Contributors: Thai-Yunnan Project. Dewey Number: 306.089959105135 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. First edition © 2001 Pandanus Books This edition © 2008 ANU E Press iv For my father CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgements xii Introduction 1 Historical Studies of the Tai Yai: A Brief Sketch 3 The Ethnography of Tai Yai in Yunnan 8 Ethnic Identity and the Construction of an Imagined Tai Community 12 Scope and Purpose of this Study 16 Chapter One: The Setting 19 Daikong and the Chinese Revolution 20 Land Reform 22 Tai Peasants and Cooperative Farming 23 The Commune 27 Daikong and the Cultural Revolution 31 Lak -

Sociolinguistic Survey of Mpi in Thailand

Sociolinguistic Survey of Mpi in Thailand Ramzi W. Nahhas SIL International 2007 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2007-016, August 2007 Copyright © 2007 Ramzi W. Nahhas and SIL International All rights reserved 2 Abstract Ramzi W. Nahhas, PhD Survey Unit, Department of Linguistics School of Graduate Studies Payap University/SIL International Chiang Mai, Thailand Mpi is a language spoken mainly in only two villages in Thailand, and possibly in one location in China, as well. Currently, Mpi does not have vernacular literature, and may not have sufficient language vitality to warrant the development of such literature. Since there are only two Mpi villages in Thailand, and they are surrounded by Northern Thai communities, it is reasonable to be concerned about the vitality of the Mpi language. The purposes of this study were to assess the need for vernacular literature development among the Mpi of Northern Thailand and to determine which (if any) Mpi varieties should be developed. This assessment focused on language vitality and bilingualism in Northern Thai. Additionally, lexicostatistics were used to measure lexical similarity between Mpi varieties. Acknowledgments This research was conducted under the auspices of the Payap University Linguistics Department, Chiang Mai, Thailand. The research team consisted of the author, Jenvit Suknaphasawat (SIL International), and Noel Mann (Technical Director, Survey Unit, Payap University Linguistics Department, and SIL International). The fieldwork would not have been possible without the assistance of the residents of Ban Dong (in Phrae Province) and Ban Sakoen (in Nan Province). A number of individuals gave many hours to help the researchers learn about the Mpi people and about their village, and to introduce us to others in their village. -

Contemporary Phuthai Textiles

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 Contemporary Phuthai Textiles Linda S. McIntosh Simon Fraser University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons McIntosh, Linda S., "Contemporary Phuthai Textiles" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 481. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/481 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Contemporary Phuthai Textiles Linda S. McIntosh Simon Fraser University [email protected] © Linda S. McIntosh 2004 The hand-woven textiles of the Phuthai ethnic group continue to represent Phuthai identity but also reflect exposure to foreign elements such as through trade and changes in the regional political power. If one asks a Phuthai woman what is Phuthai dress, she will answer, sin mii lae suea lap lai, or a skirt decorated with weft ikat technique and a fitted blouse of indigo dyed cotton, decorated with hand-woven, patterned red silk. Despite the use of synthetic dyes readily available in the local markets, many women still grow indigo and cotton, and indigo-stained hands and the repetitious sounds of weaving are still found in Phuthai villages. This paper focuses on the Phuthai living in Savannakhet Province, Laos, but they are also found in Khammuan, Bolikhamsay, and Salavan provinces of Laos as well as in Thailand and Vietnam.1 Contemporary refers to textile production in the last thirty years but particularly in the last ten years after the liberalization of the Lao government policies and the return of private business and tourism after the 1980s. -

Volume 4-2:2011

JSEALS Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Managing Editor: Paul Sidwell (Pacific Linguistics, Canberra) Editorial Advisory Board: Mark Alves (USA) George Bedell (Thailand) Marc Brunelle (Canada) Gerard Diffloth (Cambodia) Marlys Macken (USA) Brian Migliazza (USA) Keralapura Nagaraja (India) Peter Norquest (USA) Amara Prasithrathsint (Thailand) Martha Ratliff (USA) Sophana Srichampa (Thailand) Justin Watkins (UK) JSEALS is the peer-reviewed journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, and is devoted to publishing research on the languages of mainland and insular Southeast Asia. It is an electronic journal, distributed freely by Pacific Linguistics (www.pacling.com) and the JSEALS website (jseals.org). JSEALS was formally established by decision of the SEALS 17 meeting, held at the University of Maryland in September 2007. It supersedes the Conference Proceedings, previously published by Arizona State University and later by Pacific Linguistics. JSEALS welcomes articles that are topical, focused on linguistic (as opposed to cultural or anthropological) issues, and which further the lively debate that characterizes the annual SEALS conferences. Although we expect in practice that most JSEALS articles will have been presented and discussed at the SEALS conference, submission is open to all regardless of their participation in SEALS meetings. Papers are expected to be written in English. Each paper is reviewed by at least two scholars, usually a member of the Advisory Board and one or more independent readers. Reviewers are volunteers, and we are grateful for their assistance in ensuring the quality of this publication. As an additional service we also admit data papers, reports and notes, subject to an internal review process. -

Iron Man of Laos Prince Phetsarath Ratanavongsa the Cornell University Southeast Asia Program

* fll!!I ''{f'':" ' J.,, .,.,Pc, IRON MAN OF LAOS PRINCE PHETSARATH RATANAVONGSA THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual countries of the area: Brunei, Burma, Indonesia, Kampuchea, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in Southeast Asian cultural history and present-day affairs and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on linguistic studies of the languages of the area. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, requirements for degrees, and current course offerings is obtainable· from the Director, Southeast Asia Program, 120 Uris Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853. 11 IRON MAN OF LAOS PRINCE PHETSARATH RATANAVONGSA by "3349" Trc1nslated by .John B. �1urdoch F.di ted by · David K. \-vyatt Data Paper: Number 110 -Southeast Asia Program Department of Asian Studies Cornell University, Ithaca, New York .November 197·8 Price: $5.00 111 CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM 1978 International Standard Book Number 0-87727-110-0 iv C.ONTENTS FOREWORD • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . -

The Kinship Relations of Thai-Lao Communities Along Mekong River Banks: a Case of Mukdahan-Savannakhet Community and Recommendations for Improving Thai-Lao Relations*

Research Articles The kinship relations of Thai-Lao communities along Mekong River banks: a case of Mukdahan-Savannakhet community and recommendations for improving Thai-Lao Relations* Watunyu Jaiborisudhi1*, Wichian Intasi1 and Ampa Kaewkumkong1 1Institute of East Asian Studies, Thammasat University, Pathum Thani, 12121, Thailand. Abstract Background: The bilateral relations between Thailand and Laos were initially based on a good perception for a long time. It can be said that Thai policy towards relations with Laos was adhered to the old discourse, which believed that Thailand and Laos are Sister Countries, and thus presumed the close tie between them. While Thai myth believed that they were strong bilateral relations, Lao people, on the contrary, believed that the aforementioned discourse implied an insult of Thai people towards Laotian. Objective: 1. To study the cause of the problems concerning the bilateral relations between Thailand and Laos. 2. To study the relative advantage of the bilateral relations between Thailand and Laos. Results: The study of the comparison of the advantage and disadvantage between Thailand and Vietnam on the relationship with Lao showed that Thailand was relatively disadvantaged in comparison to Vietnam in all aspects. However, the Researcher has proposed the advantage that Thailand possesses over the bilateral relations between Thailand and Laos, namely, the kinship relations of the communities along both Mekong River banks included Mukdahan-Savannakhet community which was closely sustained. Discussion: This research is to study the causes of the bilateral relations problem, and to present the advantages over the improving of the bilateral relations between Thailand and Laos under the historical research and the concept of National interest. -

غhistorical Presentations in the Lao Textbooks

Historical Presentations in the Lao Textbooks: From the Independent to the Early Socialism Period (1949-1986)1 Dararat Mattariganond Û Yaowalak Apichatvullop This paper presents the presentations of Lao history in the Lao textbooks from the Independent period, starting in 1949 to the Early Socialism period, starting in 1975. We designate the year 1949 as the starting point of our study as it was this year that the Royal Lao Government (RLG) proclaimed independence from France on 19 July. It was also this year that Lao gained international recognition as an independent state, although it was still within the French Union. At the other end, we take the year 1986, as it was the year that the Lao Government declared the new policy çJintanakarn Mai,é which involved a number of changes in Lao 1 Paper presented in First International Conference on Lao Studies, organized by Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL, May 20-22, 2005. 88 «“√ “√ —ߧ¡≈ÿà¡πÈ”‚¢ß social structures. Our purpose is to show that history was manipulated by the Lao governments of both periods as a mechanism to transfer the national social values to the younger generations through textbooks used in school education. Our analysis is based on the Lao textbooks used during the Independent and the Socialism periods (1949- 1986). Presentations of this paper are in two parts: 1) the Lao history in the Lao textbooks of the Independent period (1949-1975), and 2) the Lao history in the Lao textbooks of the Early Socialism period (1975-1986). 1. Lao History Before 1975 Based on Lao historical documents, the Lan Xang kingdom used to be a well united state during King Fa Ngumûs regime.