The Banality of Corporate Evil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Strange Loop

A Strange Loop / Who we are Our vision We believe in theater as the most human and immediate medium to tell the stories of our time, and affirm the primacy and centrality of the playwright to the form. Our writers We support each playwright’s full creative development and nurture their unique voice, resulting in a heterogeneous mix of as many styles as there are artists. Our productions We share the stories of today by the writers of tomorrow. These intrepid, diverse artists develop plays and musicals that are relevant, intelligent, and boundary-pushing. Our plays reflect the world around us through stories that can only be told on stage. Our audience Much like our work, the 60,000 people who join us each year are curious and adventurous. Playwrights is committed to engaging and developing audiences to sustain the future of American theater. That’s why we offer affordably priced tickets to every performance to young people and others, and provide engaging content — both onsite and online — to delight and inspire new play lovers in NYC, around the country, and throughout the world. Our process We meet the individual needs of each writer in order to develop their work further. Our New Works Lab produces readings and workshops to cultivate our artists’ new projects. Through our robust commissioning program and open script submission policy, we identify and cultivate the most exciting American talent and help bring their unique vision to life. Our downtown programs …reflect and deepen our mission in numerous ways, including the innovative curriculum at our Theater School, mutually beneficial collaborations with our Resident Companies, and welcoming myriad arts and education not-for-profits that operate their programs in our studios. -

Song List by Member

song artist album label dj year-month-order leaf house animal collective sung tongs 2004-08-02 bebete vaohora jorge ben the definitive collection 2004-08-08 amor brasileiro vinicius cantuaria tucuma 2004-08-09 crayon manitoba up in flames 2004-08-10 transit fennesz venice 2004-08-11 cold irons bound bob dylan time out of mind 2004-08-13 mini, mini, mini jacques dutronc en vogue 2004-08-14 unspoken four tet rounds 2004-08-15 dead homiez ice cube kill at will 2004-08-16 forever's no time at all pete townsend who came first 2004-08-17 mockingbird trailer bride hope is a thing with feathers 2004-08-18 call 1-800 fear lali puna faking the books 2004-08-19 vuelvo al sur gotan project la revancha del tango 2004-08-21 brick house commodores pure funk polygram tv adam 1998-10-09 louis armstrong - the jazz collector mack the knife louis armstrong edition laserlight adam 1998-10-18 harry and maggie swervedriver adam h. 2012-04-02 dust devil school of seven bells escape from desire adam h. 2012-04-13 come on my skeleton plug back on time adam h. 2012-09-05 elephant tame impala elephant adam h. 2012-09-09 day one toro y moi everything in return adam h. 2014-03-01 thank dub bill callahan have fun with god adam h. 2014-03-10 the other side of summer elvis costello spike warner bros. adam s (#2) 2006-01-04 wrong band tori amos under the pink atlantic adam s (#2) 2006-01-12 Baby Lemonade Syd Barrett Barrett Adam S. -

Barbican.Org.Uk Ll.Com

RAYMOND GUBBAYpresents FORTHCOMING CONCERTSATTHE ROYALALBERTHALL Saturday 23 September at 7.30pm Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Beethoven’sNinth London Philharmonic Choir Andrew Nethsingha conductor An unmissable all-Beethoven concert culminates Federico Colli piano with the monumental ‘Choral Symphony’. Ailish Tynan soprano Justina Gringyte mezzo-soprano Piano Concerto No.5 ‘Emperor’ Robert Murray tenor Symphony No.9 ‘Choral’ Jonathan Lemalu bass Sunday 8October at 3.00pm Grand Organ Gala 10,000 organ pipes in glorious harmony. Celebrate Royal Philharmonic Orchestra the power and majesty of the king of instruments. City of London Choir Saint-Saëns - Symphony No. 3 ‘Organ’ Hilary Davan Wetton conductor Parry - I was Glad Laura Mitchell soprano Fauré - Pie Jesu & In paradisum from Requiem Philip Scriven organ Strauss - Sunrise from Also sprach Zarathustra Fanfare Trumpeters of Bach - Toccata & Fugue in D minor the Band of the Royal Logistics Corps Mussorgsky - Great Gate at Kiev Handel - Hallelujah Chorus Widor - Toccata Elgar - Land of Hope and Glory Saturday 28 October at 7.30pm Royal Philharmonic Orchestra English Concert Chorus Carmina Burana Highgate Choral Society Royal Choral Society Returns by popular demand -witness Orff’s choral Southend Boys’ Choir extravaganza performedbyover 400 voices. Andrew Greenwood conductor Rossini - William Tell Overture Jennifer Pike violin Jennifer France soprano Bruch - Violin Concerto No.1 sep17 Thomas Walker tenor Orff - Carmina Burana David Kempster baritone ROYAL ALBERTHALL BOX OFFICE 020 7838 3109 -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

THE WHOLEHEARTED Is Made Possible with Funding by the New England Foundation for the Arts’ National Theater Project, with Lead Funding from the Andrew W

THE WHOLEHEARTED is made possible with funding by the New England Foundation for the Arts’ National Theater Project, with lead funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. March 15 - April 1, 2018 15 - March STEIN | HOLUM PROJECTS THE WHOLEHEARTED STEIN | HOLUM PROJECTS WHO’S THE WHOLEHEARTED WHO Conceived and Created by THE WHOLEHEARTED was commissioned STEIN | HOLUM PROJECTS (SHP) is the Stein | Holum Projects and first presented by ArtsEmerson: ongoing creative partnership of Suli Written and Directed by Deborah Stein The World On Stage in April 2014. A Holum and Deborah Stein. Drawing on late-stage completion residency and over a decade of experience in both Performed and Directed by Suli Holum * performances was provided by Z Space experimental and regional theatre, SHP Onstage Camera and Video Engineer in San Francisco in September 2016. works with a core group of designers Stivo Arnoczy Additional workshop residencies have to create a unique hybrid of the been provided by HERE, the Lower highly visual and dexterously verbal; Sound Design Manhattan Cultural Council (Swing interdisciplinary physical theater with Matt Hubbs and James Sugg Space), the Orchard Project, Kelly complex and nuanced characters. Our Original Music Strayhorn, Philadelphia FringeArts, first play, CHIMERA, was developed James Sugg and Heather Christian Swarthmore College Project in Theatre, with a HARP residency and premiered Set Design Amy Rubin New Dramatists Creativity Fund (with in 2012 at HERE as part of Under the the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Radar, where it was a NY Times Critics’ Video Design Foundation), and JACK (with the support Pick and nominated for a Drama Desk Katherine Freer and Dave Tennent of the Brooklyn Arts Council). -

Song List by Artist

song artist album label dj year-month-order sample of the whistled language silbo Nina 2006-04-10 rich man’s frug (video - movie clip) sweet charity Nayland 2008-03-07 dungeon ballet (video - movie clip) 5,000 fingers of dr. t Nayland 2008-03-08 plainfin midshipman the diversity of animal sounds Nina 2008-10-10 my bathroom the bathrooms are coming Nayland 2010-05-03 the billy bee song Nayland 2013-11-09 bootsie the elf bootsie the elf Nayland 2013-12-10 david bowie, brian eno and tony visconti record 'warszawa' Dan 2015-04-03 "22" with little red, tangle eye, & early in the mornin' hard hair prison songs vol 1: murderous home rounder alison 1998-04-14 phil's baby (found by jaime fillmore) the relay project (audio magazine) Nina 2006-01-02 [unknown title] [unknown artist] cambodian rocks (track 22) parallel world bryan 2000-10-01 hey jude (youtube video) [unknown] Nina 2008-03-09 carry on my wayward son (youtube video) [unknown] Nina 2008-03-10 Sri Vidya Shrine Prayer [unknown] [no album] Nina 2016-07-04 Sasalimpetan [unknown] Seleksi Tembang Cantik Tom B. 2018-11-08 i'm mandy, fly me 10cc changing faces, the best of 10cc and polydor godley & crème Dan 2003-01-04 animal speaks 15.60.76 jimmy bell's still in town Brian 2010-05-02 derelicts of dialect 3rd bass derelicts of dialect sony Brian 2001-08-09 naima (remix) 4hero Dan 2010-11-04 magical dream 808 state tim s. 2013-03-13 punchbag a band of bees sunshine hit me astralwerks derick 2004-01-10 We got it from Here...Thank You 4 We the People... -

Musik | the Magnetic Fields: 50 Song Memoir

Folkdays… ›50 Song Memoir‹ Musik | The Magnetic Fields: 50 Song Memoir Folkdays… ›50 Song Memoir‹ von The Magnetic Fields – Teil II über Stephin Merritt und seine Selbstsucht und Ichbezogenheit. Von TINA KAROLINA STAUNER Stephin Merritt sieht sich gern im Mittelpunkt. Es gibt ein Album des Egozentrikers, das mit ›I‹ betitelt ist und bei dem fast alle Songs mit dem Wort »I« beginnen. I…, I…, I…, I…, I… von ›I Was Born‹ bis ›I Die‹ und dann hat er auf einem Nachfolgealbum mit Titel ›Realism‹ eine lebensfrohe Polka für sich und für alle: »…People of Earth, when you dance Dance the Dada Polka Life is only a dream When in the mood for romance Dance the Dada Polka Be as cute as you seem…« Jetzt ist das neue Konzeptalbum ›50 Song Memoir‹ veröffentlicht, das Stephin Merritts eigene Existenz wieder einmal ins Zentrum stellt: Es gibt für jedes seiner bisherigen Lebensjahre einen Song. Mit umfangreichem Instrumentarium wurden die Aufnahmen für ›50 Song Memoir‹ zu hübsch bis schrägem Synthie-Folk-Pop gemacht. Mit etwas Retrogetue und nostalgischer Romantik. Nett angereichert mit einer Prise Humor. Alles kleine Geschichten. Jedenfalls klingt dieses Werk nicht nach schwerwiegender Vergangenheitsbewältigung. Es hört sich nach Pop an und sonst nach nicht allzu viel mehr. Aber immerhin nach allem Möglichen aus der Popgeschichte. Und darin fungiert Stephin Merritt offenbar lässig-leicht als Mastermind und Multiinstrumentalist. Wieso sollte er es sich schwerer machen, wenn es auch etwas leichtgewchtig geht!? 50 Lieder, 100 Musikinstrumente und Pop-Sounddesign irgendwo zwischen Independent und Mainstream. Und das alles nicht übermäßig avantgardistisch, sondern immer auch ein wenig Vintage. -

STG Presents an Average of 600 Events Annually at the Paramount, the Moore, and the Neptune Theatres As Well As at Other Venues Throughout the Region

STG presents an average of 600 events annually at The Paramount, The Moore, and The Neptune Theatres as well as at other venues throughout the region. Broadway productions, concerts, comedy, lectures, education & community programs, film, and other enrichment programs can be found in our venues. Please see below for a chronological list of performances. ● THING - CANCELLED - - Fort Worden ● AIN'T TOO PROUD - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● Black Pumas - POSTPONED - - The Paramount Theatre ● John Hiatt & The Jerry Douglas Band - POSTPONED - - The Moore Theatre ● DANCE This! Virtual Performance - August 13, 2021 - Online ● Pop-Up Mini Golf at the Paramount Theatre - August 12 - 15 - The Paramount Theatre ● Tiny Meat Gang - CANCELLED - - The Moore Theatre ● Tune-Yards - August 7, 2021 - The Neptune Theatre ● Palaye Royale - POSTPONED - - The Neptune Theatre ● Joe Russo's Almost Dead - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● The Decemberists - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● Up Next: Summer 2021 Series - July 24 - August 28, 2021 - Starbucks SODO Reserve ● The Masked Singer Live - CANCELLED - - The Paramount Theatre ● Jason Isbell and The 400 Unit - POSTPONED - - The Paramount Theatre ● IRC Residency - July 12, 2021 - Cascade View Elementary ● Girls Gotta Eat - POSTPONED - - The Moore Theatre ● More Music Songwriters Sessions 2021 - July 7, 2021 - Online ● STG Virtual AileyCamp 2021 - July 7 - August 4, 2021 - Online ● Pop-Up Donor Center with Bloodworks Northwest at The Paramount - July 6 - 9, 2021 - The Paramount Theatre ● Brit -

2016-2017 Season Show Descriptions Snap Judgment Live

2016-2017 Season Show Descriptions Snap Judgment Live Moore Friday, October 7, 2016 SNAP JUDGMENT is the storytelling phenomena electriFying audiences nationwide. Created by Glynn Washington and co-produced by WNYC, Snap delivers a raw, intimate, musical brand oF narrative - daring audiences to see the world through the eyes oF another. SNAP JUDGMENT LIVE Features the world's Finest storytellers, on stage, backed by the SNAP JUDGMENT band. We ask Snap storytellers to dig deep, and marvel as they create magic. SNAP JUDGMENT craFts powerful multi-platForm experiences (radio, stage, screen, web) that deliver raw, intimate narratives - giving audiences a glimpse into the lives oF a stranger. Pop, Lecture Simply Three Moore Saturday, October 8, 2016 The electriFying trio oF Glen McDaniel, Nick Villalobos, and Zack Clark, together known as SIMPLY THREE, has been captivating audiences worldwide with high- octane performances since 2010. Acclaimed as “having what it takes” (Boston Philharmonic) and “highly imaginative and well played” (Maine Today), SIMPLY THREE continues to receive praise For their ability to impress listeners with a multitude oF genres that span From Puccini and Gershwin to artists such as Adele, Coldplay, and Michael Jackson. By reshaping convention through this style oF genre hopping, the trio continues to seek the true essence oF classical crossover with original works as well as innovative arrangements that showcase their technical virtuosity and heartFelt musicality. SIMPLY THREE has old school training but a new school sound. Their quest to look beyond the scope oF possibility has led them to collaborate with some oF the world’s most creative musicians, including Kellindo Parker (Janelle Monáe) and JeFF Smith (M-Pact), in hopes oF creating a new, Fresh genesis For string playing. -

The Magnetic Fields

Folkdays…The Magnetic Fields Musik | The Magnetic Fields/Stephin Merritt: 69 Love Songs Song um Song über Liebe und nochmal Liebe, Surrealismus, Realismus, Liebäugelei mit automatistischem Schreiben. ›69 Love Songs‹ und 46 Liebeslieder hat TINA KAROLINA STAUNER gehört. Stephin Merritt gründete 1990 die Bostoner Band The Magnetc Fields. Entstanden aus dem Projekt Buffalo Rome. Merritt dachte dabei an André Breton und Philippe Soupault und deren Buch ›Les Champs Magnétiques‹, 1919 als erster Text des Surrealismus veröffentlicht. Es gibt eine deutsche Übersetzung von Ré Soupault ergänzend: ›Die magnetischen Felder‹ – Surrealismus, automatistisches Schreiben. Stephin Merritts Magnetic Fields waren oder sind mal mehr keyboardlastiger Indie-Rock und mal mehr Indie-Folk-Pop, spielend auch mit Noiseelementen und verortet im Lo-Fi. Sie verirrten sich im Sound manchmal auch im schaurig-hübschen 60’s Pop. Mitglieder der Band sind neben dem 52-jährigen Stephin Merritt: Claudia Gonson, Sam Davol, John Woo, Shirley Simms und früher einmal Susan Anway – mit der Instrumentierung: Ukulele, Banjo, Mandoline, Accordion, Cello, Flute, Piano, Guitars, Percussion, Synthesizer und mal einigen und mal vielen weiteren Instrumenten. Gerade wurde das Album ›50 Song Memoir‹ der Band veröffentlicht. Die Magnetc Fields fielen mir erstmals 1999 mit ihrem siebten Album ›69 Love Songs‹ besonders auf. Es inspirierte mich zu einer essayistischen Rezension über die Arbeit und Welt der Magnetc Fields und über den Denkversuch Stephin Merritts genannt ›69 Love Songs‹: Stephin -

Order Form Full

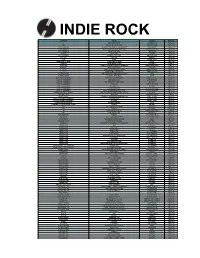

INDIE ROCK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 68 TWO PARTS VIPER COOKING VINYL RM128.00 *ASK DISCIPLINE & PRESSURE GROUND SOUND RM100.00 10, 000 MANIACS IN THE CITY OF ANGELS - 1993 BROADC PARACHUTE RM151.00 10, 000 MANIACS MUSIC FROM THE MOTION PICTURE ORIGINAL RECORD RM133.00 10, 000 MANIACS TWICE TOLD TALES CLEOPATRA RM108.00 12 RODS LOST TIME CHIGLIAK RM100.00 16 HORSEPOWER SACKCLOTH'N'ASHES MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 1975, THE THE 1975 VAGRANT RM140.00 1990S KICKS ROUGH TRADE RM100.00 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS VIRGIN RM132.00 31 KNOTS TRUMP HARM (180 GR) POLYVINYL RM95.00 400 BLOWS ANGEL'S TRUMPETS & DEVIL'S TROMBONE NARNACK RECORDS RM83.00 45 GRAVE PICK YOUR POISON FRONTIER RM93.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S BOMB THE ROCKS: EARLY DAYS SWEET NOTHING RM142.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S TEENAGE MOJO WORKOUT SWEET NOTHING RM129.00 A CERTAIN RATIO THE GRAVEYARD AND THE BALLROOM MUTE RM133.00 A CERTAIN RATIO TO EACH... (RED VINYL) MUTE RM133.00 A CITY SAFE FROM SEA THROW ME THROUGH WALLS MAGIC BULLET RM74.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER BAD VIBRATIONS ADTR RECORDS RM116.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR THOSE WHO HAVE HEART VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER HOMESICK VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD (PIC) VICTORY RECORDS RM111.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER WHAT SEPARATES ME FROM YOU VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVES HAVE YOU SEEN MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX? TOPSHELF RM103.00 A LIFE ONCE LOST IRON GAG SUBURBAN HOME RM99.00 A MINOR FOREST FLEMISH ALTRUISM/ININDEPENDENCE (RS THRILL JOCKEY RM135.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS TRANSFIXIATION DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS WORSHIP DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A SUNNY DAY IN GLASGOW SEA WHEN ABSENT LEFSE RM101.00 A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN ATOMOS KRANKY RM128.00 A.F.I. -

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 5Th March, 2017 Compiled by the Music Network© FREE SIGN UP

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 5th March, 2017 Compiled by The Music Network© FREE SIGN UP ARTIST TOP 50 Combines airplay, downloads & streams #1 SINGLE ACROSS AUSTRALIA shape of you 1 Ed Sheeran | WMA Shape of you i don't wanna live forever Ed Sheeran | WMA 2 ZAYN & Taylor Swift | UMA chained to the rhythm 3 Katy Perry | EMI Back at #1, and clocking up its fifth non-consecutive week in that position, is Ed Sheeran’sShape Of it ain't me You. It briefly lost the top spot last week to ZAYN & Taylor Swift’s I Don’t Wanna Live Forever. Cracking 4 Kygo & Selena Gomez | SME the Top 20 at #4 from #42 is Kygo’s It Ain’t Me ft. Selena Gomez. Jon Bellion earns a new peak at #8 5 fresh eyes with breakthrough single All Time Low, moving up from #10, as does Bruno Mars’ That’s What I Like at Andy Grammer | MUSH #9 from #13. 6 castle on the hill Ed Sheeran | WMA The first new debuts come in at #16 and #17. First up is Ed Sheeran’s latest, How Would You Feel. Next paris 7 The Chainsmokers | SME is The Chainsmokers & Coldplay’s huge collaboration Something Just Like This. Maroon 5 mark the all time low last noteworthy change at #18 as their new single Cold ft. Future enters the Top 20 from #32 on its 8 Jon Bellion | EMI second week in the chart. that's what i like 9 Bruno Mars | WMA adore 10 Amy Shark | SME capsize #1 MOST ADDED TO RADIO 11 Frenship | SME you don't know me Slide 12 Jax Jones | ETC/UMA Calvin Harris ft.