Expressions of Language Ideologies and Attitudes in Four Namibian Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Parameters of Morpho-Syntactic Variation

This paper appeared in: Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 105:3 (2007) 253–338. Please always use the published version for citation. PARAMETERS OF MORPHO-SYNTACTIC VARIATION IN BANTU* a b c By LUTZ MARTEN , NANCY C. KULA AND NHLANHLA THWALA a School of Oriental and African Studies, b University of Leiden and School of Oriental and African Studies, c University of the Witwatersrand and School of Oriental and African Studies ABSTRACT Bantu languages are fairly uniform in terms of broad typological parameters. However, they have been noted to display a high degree or more fine-grained morpho-syntactic micro-variation. In this paper we develop a systematic approach to the study of morpho-syntactic variation in Bantu by developing 19 parameters which serve as the basis for cross-linguistic comparison and which we use for comparing ten south-eastern Bantu languages. We address conceptual issues involved in studying morpho-syntax along parametric lines and show how the data we have can be used for the quantitative study of language comparison. Although the work reported is a case study in need of expansion, we will show that it nevertheless produces relevant results. 1. INTRODUCTION Early studies of morphological and syntactic linguistic variation were mostly aimed at providing broad parameters according to which the languages of the world differ. The classification of languages into ‘inflectional’, ‘agglutinating’, and ‘isolating’ morphological types, originating from the work of Humboldt (1836), is a well-known example of this approach. Subsequent studies in linguistic typology, e.g. work following Greenberg (1963), similarly tried to formulate variables which could be applied to any language and which would classify languages into a number of different types. -

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

Contributions to the Study of African Languages from the Nordic Countries Arvi Hurskainen

Contributions to the study of African languages from the Nordic countries Arvi Hurskainen 1 Introduction This chapter gives an outline of the study of African languages in various Nordic countries. The description is limited to the work of individual researchers as far as it was financed by these countries. Therefore, the work of each researcher is included only as far as the above criterion is fulfilled. Research of African languages has often been carried out as part of study on general linguistics, or other such research area that has made it possible to study also African languages. Only the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, has a professorship dedicated to the study of African languages. In Norway and Denmark, African languages have been studied mostly in departments of general linguistics. In Finland, the professorship at the University of Helsinki is defined as African studies, that is, the wide research field makes it possible to study also such subjects that normally would be studied in other departments - anthropology and history, for example. 2 Early initiatives The motivation for studying African languages emerged initially as part of missionary activities. There was a need to be able to communicate using local languages. Missionaries had to learn the languages, and this was made possible by producing grammars and dictionaries. The pioneers had seldom formal linguistic training. Yet they produced valuable resources for many languages, which up today have remained standard language resources of those languages. The work of missionaries also included the creation of orthographies and production of teaching materials for schools. Finally, their contribution extends to such achievements as the translation of Bible or its parts to local languages. -

Voicing on the Fringe: Towards an Analysis of ‘Quirkyʼ Phonology in Ju and Beyond

Voicing on the fringe: towards an analysis of ‘quirkyʼ phonology in Ju and beyond Lee J. Pratchett Abstract The binary voice contrast is a productive feature of the sound systems of Khoisan languages but is especially pervasive in Ju (Kx’a) and Taa (Tuu) in which it yields phonologically contrastive segments with phonetically complex gestures like click clusters. This paper investigates further the stability of these ‘quirky’ segments in the Ju language complex in light of new data from under-documented varieties spoken in Botswana that demonstrate an almost systematic devoicing of such segments, pointing to a sound change in progress in varieties that one might least expect. After outlining a multi-causal explanation of this phenomenon, the investigation shifts to a diachronic enquiry. In the spirit of Anthony Traill (2001), using the most recent knowledge on Khoisan languages, this paper seeks to unveil more on language history in the Kalahari Basin Area from these typologically and areally unique sounds. Keywords: Khoisan, historical linguistics, phonology, Ju, typology (AFRICaNa LINGUISTICa 24 (2018 100 Introduction A phonological voice distinction is common to more than two thirds of the world’s languages: whilst largely ubiquitous in African languages, a voice contrast is almost completely absent in the languages of Australia (Maddison 2013). The particularly pervasive voice dimension in Khoisan1 languages is especially interesting for two reasons. Firstly, the feature is productive even with articulatory complex combinations of clicks and other ejective consonants, gestures that, from a typological perspective, are incompatible with the realisation of voicing. Secondly, these phonological contrasts are robustly found in only two unrelated languages, Taa (Tuu) and Ju (Kx’a) (for a classification see Güldemann 2014). -

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE. The Court strongly prefers to use live interpreters in the courtrooms whenever possible. However, when the Court can’t find live interpreters, we sometimes use Language Line, a national telephone service supplying interpreters for most languages on the planet almost immediately. The number for that service is 1-800-874-9426. Contact Circuit Administration at 605-367-5920 for the Court’s account number and authorization codes. AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE/DEAF INTERPRETATION Minnehaha County in the 2nd Judicial Circuit uses a combination of local, highly credentialed ASL/Deaf interpretation providers including Communication Services for the Deaf (CSD), Interpreter Services Inc. (ISI), and highly qualified freelancers for the courts in Sioux Falls, Minnehaha County, and Canton, Lincoln County. We are also happy to make court video units available to any other courts to access these interpreters from Sioux Falls (although many providers have their own video units now). The State of South Dakota has also adopted certification requirements for ASL/deaf interpretation “in a legal setting” in 2006. The following link published by the State Department of Human Services/ Division of Rehabilitative Services lists all the certified interpreters in South Dakota and their certification levels, and provides a lot of other information on deaf interpretation requirements and services in South Dakota. DHS Deaf Services AFRICAN DIALECTS A number of the residents of the 2nd Judicial Circuit speak relatively obscure African dialects. For court staff, attorneys, and the public, this list may be of some assistance in confirming the spelling and country of origin of some of those rare African dialects. -

Josephine Ntelamo Sitwala Master of Arts

LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE IN THE MALOZI COMMUNITY OF CAPRIVI Josephine Ntelamo Sitwala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the subject SOCIOLINGUISTICS at the University of South Africa Supervisor: Prof L.A. Barnes February 2010 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. vi Abstract ............................................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction: Statement of the problem ...................................................................... 1 1.2 Aim of the study .......................................................................................................... 1 1.3 The research questions ................................................................................................ 2 1.4 The hypothesis of the study ......................................................................................... 2 1.5 Significance of the study ............................................................................................. 3 1.6 Motivation for the study .............................................................................................. 3 1.7 The Malozi and their language .................................................................................... 4 -

Pots, Words and the Bantu Problem: on Lexical Reconstruction and Early African History*

Journal of African History, 48 (2007), pp. 173–99. f 2007 Cambridge University Press 173 doi:10.1017/S002185370700254X Printed in the United Kingdom POTS, WORDS AND THE BANTU PROBLEM: ON LEXICAL RECONSTRUCTION AND EARLY AFRICAN HISTORY* BY KOEN BOSTOEN Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren, Universite´ libre de Bruxelles ABSTRACT: Historical-comparative linguistics has played a key role in the recon- struction of early history in Africa. Regarding the ‘Bantu Problem’ in particular, linguistic research, particularly language classification, has oriented historical study and been a guiding principle for both historians and archaeologists. Some historians have also embraced the comparison of cultural vocabularies as a core method for reconstructing African history. This paper evaluates the merits and limits of this latter methodology by analysing Bantu pottery vocabulary. Challenging earlier interpretations, it argues that speakers of Proto-Bantu in- herited the craft of pot-making from their Benue-Congo-speaking ancestors who introduced this technology into the Grassfields region. This ‘Proto-Bantu ceramic tradition’ was the result of a long, local development, but spread quite rapidly into Atlantic Central Africa, and possibly as far as Southern Angola and northern Namibia. The people who brought Early Iron Age (EIA) ceramics to southwestern Africa were not the first Bantu-speakers in this area nor did they introduce the technology of pot-making. KEY WORDS: Archaeology, Bantu origins, linguistics. T HE Bantu languages stretch out from Cameroon in the west to southern Somalia in the east and as far as Southern Africa in the south.1 This group of closely related languages is by far Africa’s most widespread language group. -

Language Policy for Schools in Namibia

English The Language Policy for Schools in Namibia Discussion Document January 2003 THE LANGUAGE POLICY FOR SCHOOLS IN NAMIBIA Discussion Document January 2003 Ministry of Basic Education, Sport and Culture (MBESC) Recommendation to the Discussion Document • The discussion document should be widely discussed before approval. • The discussion document and the final Language Policy for Schools in Namibia should be made available in all local languages and distributed to regional education offices, schools, teacher resource centres, parents, communities and all other stakeholders in education. © MBESC, 2003 Cover design by Bryony Simmonds First published 2003 Produced by the Upgrading African Languages Project (AfriLa), Namibia, supported by gtz and implemented by NIED P.O. Box 8016 WINDHOEK Namibia 1. Background 1.1 After Independence in March 1990, the then Ministry of Education, Youth, Culture and Sport began reviewing the language policy for schools. In order to develop a national policy, discussions were held in all regions of the country and a draft policy was developed. After lengthy discussions the agreed policy was issued in the document Education and Culture in Na- mibia: The Way Forward to 1996 in 1991. 1.2 The following criteria were taken into consideration when the policy was being developed and are still valid today: • The expectation that a language policy should facilitate the realisation of the substantive goals of education. • The equality of all national languages regardless of the number of speak- ers or the level of development of a particular language. • The cost of implementing the policy. • The fact that language is a means of transmitting culture and cultural identity. -

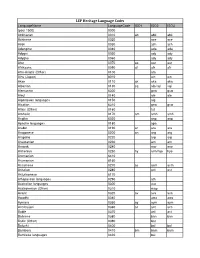

LEP Heritage Language Codes

LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 (post 1500) 0000 Abkhazian 0010 ab abk abk Achinese 0020 ace ace Acoli 0030 ach ach Adangme 0040 ada ada Adygei 0050 ady ady Adyghe 0060 ady ady Afar 0070 aa aar aar Afrikaans 0090 af afr afr Afro-Asiatic (Other) 0100 afa Ainu (Japan) 6010 ain ain Akan 0110 ak aka aka Albanian 0130 sq alb/sqi sqi Alemannic 6300 gsw gsw Aleut 0140 ale ale Algonquian languages 0150 alg Alsatian 6310 gsw gsw Altaic (Other) 0160 tut Amharic 0170 am amh amh Angika 6020 anp anp Apache languages 0180 apa Arabic 0190 ar ara ara Aragonese 0200 an arg arg Arapaho 0220 arp arp Araucanian 0230 arn arn Arawak 0240 arw arw Armenian 0250 hy arm/hye hye Aromanian 6410 Arumanian 6160 Assamese 0270 as asm asm Asturian 0280 ast ast Asturleonese 6170 Athapascan languages 0290 ath Australian languages 0300 aus Austronesian (Other) 0310 map Avaric 0320 av ava ava Awadhi 0340 awa awa Aymara 0350 ay aym aym Azerbaijani 0360 az aze aze Bable 0370 ast ast Balinese 0380 ban ban Baltic (Other) 0390 bat Baluchi 0400 bal bal Bambara 0410 bm bam bam Bamileke languages 0420 bai LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 Banda 0430 bad Bantu (Other) 0440 bnt Basa 0450 bas bas Bashkir 0460 ba bak bak Basque 0470 eu baq/eus eus Batak (Indonesia) 0480 btk Bedawiyet 6180 bej bej Beja 0490 bej bej Belarusian 0500 be bel bel Bemba 0510 bem bem Bengali; ben 0520 bn ben ben Berber (Other) 0530 ber Bhojpuri 0540 bho bho Bihari 0550 bh bih Bikol 0560 bik bik Bilin 0570 byn byn Bini 0580 bin bin Bislama -

Annales Aequatoria 2000.Pdf

ANNALES AEQUATORIA Annales quatoria 21(2000) TABLE DES MATIÈRES EDITORIAL: quatoria Bibliothèque de Base On-Line (ABBOL) 5-7 HISTOIRE Roger KAMANDA Kola, A propos de la « bantouisation » culturelle en R. D. du Congo 9-18 Stanislas LUFUNGULA Lewono, Le Foyer social de Mbandaka (Coquilhatville) 19-32 Honoré VINCK, Etat de la recherche sur les bonobos de l’Equateur (R.D.Congo). 33-40 Rosemarie M. K. EGGERT, Le rôle joué par la monnaie précoloniale, coloniale et moderne dans les transactions matrimoniales chez les Mongo de la région équatoriale de la R.D.Congo 41-51 Jozef ROOSEN, Les catéchismes du diocèse de Matadi 53-67 LINGUISTIQUE John JACOBS, Classes nominales et radicaux verbaux en lombole (Katako-Kombe) 69-82 Oscar LOWENGA La Wemboloke, Quelques chants liés aux chenilles, insectes et bestioles en otetela 83-89 MOTINGEA Mangulu, La langue des Bongando septentrionaux (Bantou C 63) 91-158 Honoré VINCK, Nsong’a Lianja. Textes Non-Mongo 159-176 Roger KAMANDA Kola, Voyelles initiales des noms mono 177-212 BIO-BIBLIOGRAPHIE John Weeks, missionnaire BMS à l’Equateur du Congo 213-223 ARCHIVALIA Les manuels scolaires coloniaux aux Archives de la BMS à Oxford 225-228 CHRONIQUE 229-269 RECENSIONS 271-279 INDEX des Annales quatoria 1980-1999 281-468 ADDENDA ET CORRIGENDA des Annales quatoria 1980-1999: 469-490 Editorial La Bibliothèque Æquatoria Online Aequatoria est née dans le contexte colonial de la première moitié du dix-neuvième siècle. Elle a trouvé un nouveau souffle dans l’éclosion d’une élite intellectuelle locale des années quatre-vingt. Aujourd’hui des circonstances apparemment contrariantes l’ont orientée vers de nouvelles initiatives. -

Optimising Learning, Education and Publishing in Africa: the Language Factor

Optimising Learning, Education and Publishing in Africa: The Language Factor A Review and Analysis of Theory and Practice in Mother-Tongue and Bilingual Education in sub-Saharan Africa Edited by Adama Ouane and Christine Glanz 3 Optimising Learning, Education and Publishing in Africa: The Language Factor A Review and Analysis of Theory and Practice in Mother-Tongue and Bilingual Education in sub-Saharan Africa Edited by Adama Ouane and Christine Glanz words on a journey learn from the past Published jointly by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL), Feldbrunnenstrasse 58, 20148 Hamburg, Germany and the Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA) / African Development Bank, P.O. Box 323, 1002, Tunis Belvédère, Tunisia © June 2011 UIL/ADEA All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material from this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorised without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided that the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material from this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission from the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Head of Publication, UIL, Feldbrunnenstrasse 58, D-20148 Hamburg, Germany (e-mail: [email protected]) or ADEA / African Development Bank, P.O. Box 323, 1002, Tunis Belvédère, Tunisia (e-mail: [email protected]). ISBN 978-92-820-1170-6 The choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this book and the opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of UNESCO or ADEA and represent no commitment on the part of the Organisations. -

43167115.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository AN EVALUATION OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NAMIBIAN LANGUAGE-IN-EDUCATION POLICY IN THE UPPER PRIMARY PHASE IN OSHANA REGION by JUSTUS KASHINDI AUSIKU submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF ARTS WITH SPECIALISATION in the subject SOCIOLINGUISTICS at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF M R MADIBA CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF L A BARNES FEBRUARY 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix ABSTRACT x ABBREVIATIONS AND EXPLANATIONS xii KEY TERMS xii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 The LiEP for Namibian Schools – An overview 4 1.2.1 Background to the policy 4 1.2.2 Aims of the policy 4 1.2.3 Provisions 5 1.2.4 Policy implementation 6 1.2.5 Policy evaluation 7 1.3 The Research Problem 7 1.3.1 Research questions 8 1.4 The Specific Objectives of the Study 8 1.5 Significance of the Study 9 1.6 Limitations of the Study 10 1.7 Organisation of the Study 10 CHAPTER 2: THEORETICAL BACKGROUND 11 2.1 Introduction 11 2.2 Language Policy Evaluation Theories 12 2.2.1 The term ‘language policy evaluation’ 12 2.2.2 The necessity for language policy evaluation 13 2.2.3 What is to be evaluated? 13 2.2.4 The types of language policy evaluation 15 2.2.5 When should evaluation be done? 16 2.2.6 Who does language policy evaluation? 17 2.3 Language Education Theories 17 2.3.1 Bilingual education 18 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2.3.1.1 Subtractive bilingual model 20 2.3.1.2