Vincent Van Gogh: How His Life Influenced His Orksw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

Edrs Price Descriptors

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 224 EA 005 958 AUTHOR Kohl, Mary TITLE Guide to Selected Art Prints. Using Art Prints in Classrooms. INSTITUTION Oregon Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Salem. PUB DATE Mar 74 NOTE 43p.; Oregon'ASCD Curriculum Bulletin v28 n322 AVAILABLE FROMOregon Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, P.O. Box 421, Salem, Oregon 9730A, ($2.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.85 DESCRIPTORS *Art Appreciation; *Art Education; *Art Expression; Color Presentation; Elementary Schools; *Painting; Space; *Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS Texture ABSTRACT A sequential framework of study, that can be individually and creatively expanded, is provided for the purpose of developing in children understanding of and enjoyment in art. .The guide indicates routes of approach to certain kinds of major art, provides historical and biographical information, clarifies certain fundamentals of art, offers some activities related to the various ,elements, and conveys some continuing enthusiasm for the yonder of art creation. The elements of art--color, line, texture, shape, space, and forms of expression--provide the structure of pictorial organization. All of the pictures recomme ded are accessible tc teachers through illustrations in famil'a art books listed in the bibliography. (Author/MLF) US DEPARTMENT OF HE/ EDUCATION & WELFAS NATIONAL INSTITUTE I EOW:AT ION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEF DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIV e THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIO ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR STATED DO NOT NECESSAR IL SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INS1 EDUCATION POSIT100. OR POL Li Vi CD CO I IP GUIDE TO SELECTED ART PRINTS by Mary Kohl 1 INTRODUCTION TO GUIDE broaden and deepen his understanding and appreciation of art. -

Memoir of Vincent Van Gogh Free Download

MEMOIR OF VINCENT VAN GOGH FREE DOWNLOAD Van Gogh-Bonger Jo,Jo Van Gogh-Bonger | 192 pages | 01 Dec 2015 | PALLAS ATHENE PUBLISHERS | 9781843681069 | English | London, United Kingdom BIOGRAPHY NEWSLETTER Memoir of Vincent van Gogh save with free shipping everyday! He discovered that the dark palette he had developed back in Holland was hopelessly out-of-date. At The Yellow Housevan Gogh hoped like-minded artists could create together. On May 8,he began painting in the hospital gardens. Almond Blossom. The search for his own idiom led him to experiment with impressionist and postimpressionist techniques and to study the prints of Japanese masters. Van Gogh was a serious and thoughtful child. Born into an upper-middle-class family, Van Gogh drew as a child and was serious, quiet, and thoughtful. It marked the beginning of van Dyck's brilliant international career. Van Gogh: the Complete Paintings. See Article History. Vincent to Theo, Nuenen, on or about Wednesday, 28 October Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Van Gogh und die Haager Schule. Archived from the original on 22 September The first was painted in Paris in and shows flowers lying on the ground. Sold to Anna Boch Auvers-sur-Oise, on or about Thursday, 10 July ; Rosenblum Wheat Field with Cypresses Athabasca University Press. The 14 paintings are optimistic, joyous and visually expressive of the burgeoning spring. Van Gogh then began to alternate between fits of madness and lucidity and was sent to the asylum in Saint-Remy for treatment. Van Gogh learned about Fernand Cormon 's atelier from Theo. -

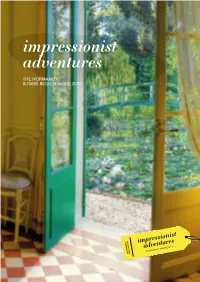

Impressionist Adventures

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

VINCENT VAN GOGH Y EL CINE Moisés BAZÁN DE HUERTA Desde

NORBA-ARTE XVII (1997) / 233-259 VINCENT VAN GOGH Y EL CINE Moisés BAZÁN DE HUERTA Desde su nacimiento, la relación del cine con las artes plásticas se ha manifes- tado en los más variados aspectos. De la influencia pictórica en el cromatismo y la configuración espacial del plano (encuadre, composición, perspectiva, profundierad), al diverso tratamiento del tiempo y los mecanismos narrativos en ambos campos; además de las bŭsquedas experimentales de las vanguardias y sus interferencias, el documental sobre arte como género, o la tradición artística como apoyo para la re- creación histórica o religiosa. También la propia pintura ha sido tratada temática- mente o como punto de partida para la reflexión sobre el proceso creativo Pero en el amplio abanico de posibilidades de esta relación, las biografías ci- nematográficas sobre artistas han sido uno de los exponentes más fructíferos, has- ta el punto de constituir casi un género propio. Dejando aparte m ŭsicos, cantantes, literatos, actores, y cifiéndonos al campo de las artes plásticas, la nómina de bio- grafiados resulta considerable: Andrei Rublev, Leonardo, Miguel Ángel, El Greco, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Velázquez, Utamaro, Fragonard, Goya, Gericault, Toulouse- Lautrec, Gauguin, Camille Claudel, Rodin, Gaudí, Pirosmani, Munch, -Carrington, Modigliani, Gaudier-Brzeska, Picasso, Dali, Goitia, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Jean Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol o Francis Bacon, entre otros, han sido objeto de re- creaciones fílmicas, aunque bastante desiguales en su calidad y planteamiento. En esta relación, como vemos, predominan las trayectorias geniales, azarosas, apasionadas y con frecuencia trágicas, es decir, las susceptibles de un desarrollo dra- mático que capte la atención y el interés del p ŭblico. -

Vincent Van Gogh, Auvers, 1890 Oil on Jute, 36 X 36 In

Vincent van Gogh, Auvers, 1890 Oil on jute, 36 x 36 in. (91.4 x 91.4 cm.) New York Private Collection Fig. 1 Vincent van Gogh, Auvers, 1890 Oil on jute, 36 x 36 in. (91.4 x 91.4 cm.) Signed on verso, ‘Vincent’ New York Private Collection Auvers,1890, Vincent van Gogh This is the discovery of a full-size van Gogh painting, one of only two in the past 100 years. The work depicts a view of a landscape at Auvers-sur-Oise, the town north of Paris where he spent the last two months of his life. The vista shows a railroad line crossing wheat fields. Auvers, 1890 (Figs. 1-13) is van Gogh’s largest and only square painting. This unique format was chosen to represent a panorama of the wheat fields of the region, of which parts are shown in many of his other paintings of the Auvers landscape. The present painting portrays the entire valley of the Oise as a mosaic of wheat fields, bisected by the right of way of a railway and a telegraph line. The center depicts a small railway station with station houses and a rail shunt, the line disappearing into the distant horizon. The painting is in its original, untouched ondition.c The support is coarse burlap on the original stretcher. The paint surface is a thick impasto that has an overall broad grid pattern of craquelure consistent with a painting of its age. The verso of the painting bears the artist’s signature, Vincent, in black pigment. -

Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Richard Thomson Vincent van Gogh The Starry Night the museum of modern art, new york The Starry Night without doubt, vincent van gogh’s painting the starry night (fig. 1) is an iconic image of modern culture. One of the beacons of The Museum of Modern Art, every day it draws thousands of visitors who want to gaze at it, be instructed about it, or be photographed in front of it. The picture has a far-flung and flexible identity in our collective musée imaginaire, whether in material form decorating a tie or T-shirt, as a visual quotation in a book cover or caricature, or as a ubiquitously understood allusion to anguish in a sentimental popular song. Starry Night belongs in the front rank of the modern cultural vernacular. This is rather a surprising status to have been achieved by a painting that was executed with neither fanfare nor much explanation in Van Gogh’s own correspondence, that on reflection the artist found did not satisfy him, and that displeased his crucial supporter and primary critic, his brother Theo. Starry Night was painted in June 1889, at a period of great complexity in Vincent’s life. Living at the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, a Dutchman in Provence, he was cut off from his country, family, and fellow artists. His isolation was enhanced by his state of health, psychologically fragile and erratic. Yet for all these taxing disadvantages, Van Gogh was determined to fulfill himself as an artist, the road that he had taken in 1880. -

The Skin of Van Gogh's Paintings Joris Dik*, Matthias Alfeld, Koen Janssens and Ella Hendriks * Dept

1788 Microsc. Microanal. 17 (Suppl 2), 2011 doi:10.1017/S1431927611009810 © Microscopy Society of America 2011 The Skin of Van Gogh's Paintings Joris Dik*, Matthias Alfeld, Koen Janssens and Ella Hendriks * Dept. of Materials Science, Delft University of Technology, Mekelweg 2, 2628CD, Delft, the Netherlands Just microns below their paint surface lay a wealth of information on Old Master Paintings. Hidden layers can include the underdrawing, the underpainting or compositional alterations by the artist. In addition, the outer surface of a paint layer may have suffered from discoloration. Thus, a look through the paint surface provides a look over the artist’s shoulder, which is crucial in technical art history, conservation issues and authenticity studies. In this contribution I will focus on the degradation mechanism of early modern painting pigments used in the work of Vincent van Gogh. These include pigments such as cadmium yellow and lead chromate yellow. Recent studies [1,2,3] of these pigments have revealed stability problems. Cadmium yellow, or cadmium sulfide, may suffer from photo-oxidation at the utmost surface of the paint film, resulting in the formation of colorless cadmium sulfate hydrates. Lead chromate, on the other hand, can be subject to a reduction process, yielding green chrome oxide at the visible surface. Obviously, such effects can seriously disfigure the original appearance of Van Gogh's oeuvre, as will be shown by a number of case studies. The degradation mechanisms were revealed using an elaborate analytical campaign, mostly involving cross-sections from the original artwork, as well as model paintings that had been aged artificially. -

SEINE RIVER CRUISE Europe | France

SEINE RIVER CRUISE Europe | France Seine River Cruise EUROPE | France Season: 2021 Standard 8 DAYS 20 MEALS 23 SITES Discover the true essence of France on this magnificent 8-day / 7-night Adventures by Disney river Seine River Cruise. From the provincial landscape of Monet’s beloved Giverny to the beaches of Normandy and stunning destinations in between, you'll engage in an exciting array of immersive entertainment and exhilarating activities. SEINE RIVER CRUISE Europe | France Trip Overview 8 DAYS / 7 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATIONS 6 LOCATIONS AmaLyra Les Andelys, Le Havre, Rouen, Vernon, Giverny, Conflans AGES FLIGHT INFORMATION 20 MEALS Minimum Age: 4 Arrive: Charles de Gaulle 7 Breakfasts, 6 Lunches, 7 Suggested Age: 8+ Airport (CDG) Dinners Return: Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG) SEINE RIVER CRUISE Europe | France DAY 1 PARIS Activities Highlights: Dinner Included Arrive in Paris, Board the Ship and Stateroom Check-in, Welcome Dinner AmaLyra On Board the Ship Arrive in Paris, France Fly into Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG) where you will be greeted by your driver who will handle your luggage and transportation to the AmaLyra ship. Board the Ship and Check-in to Your Stateroom Check into your home for the next 8 days and 7 nights—the AmaLyra—and find your luggage has been magically delivered to your stateroom. Welcome Dinner On Board the Ship Meet up with your fellow Adventurers as you toast the beginning of what promises to be an amazing adventure sailing along the beautiful Seine River through the provincial and cosmopolitan towns and cities of France. Paris Departure Begin your voyage along the Seine River with the magnificent “City of Light” lit up against the nighttime sky as a spectacular start to your Adventures by Disney river cruise adventure. -

Vincent Van Gogh Le Fou De Peinture

VINCENT VAN GOGH Le fou de peinture Texte Pascal BONAFOUX lu par l’auteur et Julien ALLOUF translated by Marguerite STORM read by Stephanie MATARD LETTRES DE VAN GOGH lues par MICHAEL LONSDALE © Éditions Thélème, Paris, 2020 CONTENTS SOMMAIRE 6 6 Anton Mauve Anton Mauve The misunderstanding of a still life Le malentendu d’une nature morte Models, and a hope Des modèles et un espoir Portraits and appearance Portraits et apparition 22 22 A home Un chez soi Bedrooms Chambres The need to copy Nécessité de la copie The destiny of the doctors’ portraits Les destins de portraits de médecins Dialogue of painters Dialogue de peintres 56 56 Churches Églises Japanese prints Estampes japonaises Arles and money Arles et l’argent Nights Nuits 74 74 Sunflowers Tournesols Trees Arbres Roots Racines 94 ARTWORK INDEX 94 index des œuvres Anton Mauve 9 /34 Anton Mauve PAGE DE DROITE Nature morte avec chou et sabots 1881 Souvenir de Mauve 1888 Still Life with Cabbage and Clogs Reminiscence of Mauve 34 x 55 cm – Huile sur papier 73 x 60 cm – Huile sur toile Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Pays-Bas Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Pays-Bas 6 7 Le malentendu d’une nature morte 10 /35 The misunderstanding of a still life Nature morte à la bible 1885 Still life with Bible 65,7 x 78,5 cm – Huile sur toile Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Pays-Bas 8 9 Souliers 1888 Shoes 45,7 x 55,2 cm – Huile sur toile The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA 10 11 Vue de la fenêtre de l’atelier de Vincent en hiver 1883 View from the window of Vincent’s studio in winter 20,7 x -

Westminsterresearch the Artist Biopic

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The artist biopic: a historical analysis of narrative cinema, 1934- 2010 Bovey, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr David Bovey, 2015. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 THE ARTIST BIOPIC: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NARRATIVE CINEMA, 1934-2010 DAVID ALLAN BOVEY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Master of Philosophy December 2015 2 ABSTRACT The thesis provides an historical overview of the artist biopic that has emerged as a distinct sub-genre of the biopic as a whole, totalling some ninety films from Europe and America alone since the first talking artist biopic in 1934. Their making usually reflects a determination on the part of the director or star to see the artist as an alter-ego. Many of them were adaptations of successful literary works, which tempted financial backers by having a ready-made audience based on a pre-established reputation. The sub-genre’s development is explored via the grouping of films with associated themes and the use of case studies. -

Annual Report 2010 Kröller-Müller Museum Introduction Mission and History Foreword Board of Trustees Mission and Historical Perspective

Annual report 2010 Kröller-Müller Museum Introduction Mission and history Foreword Board of Trustees Mission and historical perspective The Kröller-Müller Museum is a museum for the visual arts in the midst of peace, space and nature. When the museum opened its doors in 1938 its success was based upon the high quality of three factors: visual art, architecture and nature. This combination continues to define its unique character today. It is of essential importance for the museum’s future that we continue to make connections between these three elements. The museum offers visitors the opportunity to come eye-to-eye with works of art and to concentrate on the non-material side of existence. Its paradise-like setting and famous collection offer an escape from the hectic nature of daily life, while its displays and exhibitions promote an awareness of visual art’s importance in modern society. The collection has a history of almost a hundred years. The museum’s founders, Helene and Anton Kröller-Müller, were convinced early on that the collection should have an idealistic purpose and should be accessible to the public. Helene Kröller-Müller, advised by the writer and educator H.P. Bremmer and later by the entrance Kröller-Müller Museum architect and designer Henry van de Velde, cultivated an understanding of the abstract, ‘idealistic’ tendencies of the art of her time by exhibiting historical and contemporary art together. Whereas she emphasised the development of painting, in building a post-war collection, her successors have focussed upon sculpture and three-dimensional works, centred on the sculpture garden.