Art Assignment #8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artists' Journeys IMAGE NINE: Paul Gauguin. French, 1848–1903. Noa

LESSON THREE: Artists’ Journeys 19 L E S S O N S IMAGE NINE: Paul Gauguin. French, 1848–1903. IMAGE TEN: Henri Matisse. French, Noa Noa (Fragrance) from Noa Noa. 1893–94. 1869–1954. Study for “Luxe, calme et volupté.” 7 One from a series of ten woodcuts. Woodcut on 1905. Oil on canvas, 12 ⁄8 x 16" (32.7 x endgrain boxwood, printed in color with stencils. 40.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, 1 Composition: 14 x 8 ⁄16" (35.5 x 20.5 cm); sheet: New York. Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest. 1 5 15 ⁄2 x 9 ⁄8" (39.3 x 24.4 cm). Publisher: the artist, © 2005 Succession H. Matisse, Paris/Artists Paris. Printer: Louis Ray, Paris. Edition: 25–30. Rights Society (ARS), New York The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Lillie P. Bliss Collection IMAGE ELEVEN: Henri Matisse. French, 1869–1954. IMAGE TWELVE: Vasily Kandinsky. French, born Landscape at Collioure. 1905. Oil on canvas, Russia, 1866–1944. Picture with an Archer. 1909. 1 3 7 3 15 ⁄4 x 18 ⁄8" (38.8 x 46.6 cm). The Museum of Oil on canvas, 68 ⁄8 x 57 ⁄8" (175 x 144.6 cm). Modern Art, New York. Gift and Bequest of Louise The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift and Reinhardt Smith. © 2005 Succession H. Matisse, Bequest of Louise Reinhardt Smith. © 2005 Artists Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP,Paris INTRODUCTION Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists often took advantage of innovations in transportation by traveling to exotic or rural locations. -

Edrs Price Descriptors

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 224 EA 005 958 AUTHOR Kohl, Mary TITLE Guide to Selected Art Prints. Using Art Prints in Classrooms. INSTITUTION Oregon Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Salem. PUB DATE Mar 74 NOTE 43p.; Oregon'ASCD Curriculum Bulletin v28 n322 AVAILABLE FROMOregon Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, P.O. Box 421, Salem, Oregon 9730A, ($2.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.85 DESCRIPTORS *Art Appreciation; *Art Education; *Art Expression; Color Presentation; Elementary Schools; *Painting; Space; *Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS Texture ABSTRACT A sequential framework of study, that can be individually and creatively expanded, is provided for the purpose of developing in children understanding of and enjoyment in art. .The guide indicates routes of approach to certain kinds of major art, provides historical and biographical information, clarifies certain fundamentals of art, offers some activities related to the various ,elements, and conveys some continuing enthusiasm for the yonder of art creation. The elements of art--color, line, texture, shape, space, and forms of expression--provide the structure of pictorial organization. All of the pictures recomme ded are accessible tc teachers through illustrations in famil'a art books listed in the bibliography. (Author/MLF) US DEPARTMENT OF HE/ EDUCATION & WELFAS NATIONAL INSTITUTE I EOW:AT ION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEF DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIV e THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIO ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR STATED DO NOT NECESSAR IL SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INS1 EDUCATION POSIT100. OR POL Li Vi CD CO I IP GUIDE TO SELECTED ART PRINTS by Mary Kohl 1 INTRODUCTION TO GUIDE broaden and deepen his understanding and appreciation of art. -

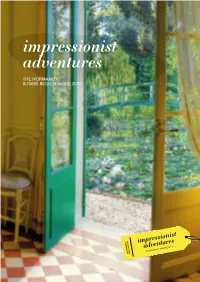

Impressionist Adventures

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

To Theo Van Gogh, the Hague, on Or About Friday, 13 July 1883

To Theo van Gogh, The Hague, on or about Friday, 13 July 1883. on or about Friday, 13 July 1883 Metadata Source status: Original manuscript Location: Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, inv. nos. b323 V/1962 (sheet 1) and b1036 V/1962 (sheet 2) Date: Vincent asks Theo to send a little extra, because he is already broke as a result of spending money in order to be able to start painting in Scheveningen (l. 49 and ll. 82-85). That places this letter after letter 361 of on or about 11 July 1883, since there he wrote that he wanted to work in Scheveningen. It must also have been written before the coming Sunday, when he is expecting a photographer (l. 79; in letter 363 this photographer indeed turns out to have come). We therefore date the letter on or about Friday, 13 July 1883. Additional: Original [1r:1] Waarde Theo, Voor ik naar Schevening ga wou ik nog even een woordje met U praten. Ik heb t maar eens doorgezet met de Bock dat ik bij hem een pied terre krijg. Misschien zal ik nu & dan bij Blommers eens aangaan ook.1 En dan is mijn plan een tijd lang Schevening geheel & al als hoofdzaak te beschouwen, smorgens er heen te gaan en den dag te blijven, of anders als ik thuis moet zijn dat thuis zijn in t middaguur te stellen als t te warm is en dan savonds er weer heen. Dit zou me nieuwe idees geven vertrouw ik, en rust, niet door stilzitten maar door verandering van omgeving en bezigheid. -

The Skin of Van Gogh's Paintings Joris Dik*, Matthias Alfeld, Koen Janssens and Ella Hendriks * Dept

1788 Microsc. Microanal. 17 (Suppl 2), 2011 doi:10.1017/S1431927611009810 © Microscopy Society of America 2011 The Skin of Van Gogh's Paintings Joris Dik*, Matthias Alfeld, Koen Janssens and Ella Hendriks * Dept. of Materials Science, Delft University of Technology, Mekelweg 2, 2628CD, Delft, the Netherlands Just microns below their paint surface lay a wealth of information on Old Master Paintings. Hidden layers can include the underdrawing, the underpainting or compositional alterations by the artist. In addition, the outer surface of a paint layer may have suffered from discoloration. Thus, a look through the paint surface provides a look over the artist’s shoulder, which is crucial in technical art history, conservation issues and authenticity studies. In this contribution I will focus on the degradation mechanism of early modern painting pigments used in the work of Vincent van Gogh. These include pigments such as cadmium yellow and lead chromate yellow. Recent studies [1,2,3] of these pigments have revealed stability problems. Cadmium yellow, or cadmium sulfide, may suffer from photo-oxidation at the utmost surface of the paint film, resulting in the formation of colorless cadmium sulfate hydrates. Lead chromate, on the other hand, can be subject to a reduction process, yielding green chrome oxide at the visible surface. Obviously, such effects can seriously disfigure the original appearance of Van Gogh's oeuvre, as will be shown by a number of case studies. The degradation mechanisms were revealed using an elaborate analytical campaign, mostly involving cross-sections from the original artwork, as well as model paintings that had been aged artificially. -

CHS 57 Philemon

Sermon #3103 Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit 1 A PASTORAL VISIT NO. 3103 A SERMON PUBLISHED ON THURSDAY, JULY 30, 1908. DELIVERED BY C. H. SPURGEON, AT THE METROPOLITAN TABERNACLE, NEWINGTON. “The Church in your house.” Philemon 1:2. SOME interpreters have supposed that a small congregation met for worship in a room in Philemon’s house and there is a tradition that such was the case for some considerable time. The Churches established by Paul were, at their commencement, for the most part small. Obliged—for the sake of peace and to avoid persecution—to meet in out of-the-way places where they were not likely to be seen by foes, the retired house of some well-known friend, perhaps that of the minister, if it had a room conveniently large, would be the natural place for Believers to gather together in those early Churches. Philemon, therefore, might literally have had a Church in his house and a congregation might have gathered there. It strikes me that there would be a great deal of good done if persons who have large rooms in their houses would endeavor to get together little congregations. There are many, even of our poorer friends, who live in neighborhoods of London destitute of the means of Grace, who might promote a great blessing if they occasionally opened their houses for a Prayer Meeting or religious assembly. We need no consecrated places for the worship of God— “Wherever we seek Him, He is found, And every place is hallowed ground.” Certainly our text does not give any countenance to the calling of certain buildings “Churches.” Buildings for worship, whether erected by Episcopalians or Dissenters, are frequently called “Churches.” If I ask for “the church” in any town, I am forthwith directed to an edifice, probably with a spire or a steeple, which the inhabitants call “the church.” Why, they might as well point me to a signpost when I asked for a man—a building cannot be a Church! A Church is an assembly of faithful men and it cannot be anything else. -

SEINE RIVER CRUISE Europe | France

SEINE RIVER CRUISE Europe | France Seine River Cruise EUROPE | France Season: 2021 Standard 8 DAYS 20 MEALS 23 SITES Discover the true essence of France on this magnificent 8-day / 7-night Adventures by Disney river Seine River Cruise. From the provincial landscape of Monet’s beloved Giverny to the beaches of Normandy and stunning destinations in between, you'll engage in an exciting array of immersive entertainment and exhilarating activities. SEINE RIVER CRUISE Europe | France Trip Overview 8 DAYS / 7 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATIONS 6 LOCATIONS AmaLyra Les Andelys, Le Havre, Rouen, Vernon, Giverny, Conflans AGES FLIGHT INFORMATION 20 MEALS Minimum Age: 4 Arrive: Charles de Gaulle 7 Breakfasts, 6 Lunches, 7 Suggested Age: 8+ Airport (CDG) Dinners Return: Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG) SEINE RIVER CRUISE Europe | France DAY 1 PARIS Activities Highlights: Dinner Included Arrive in Paris, Board the Ship and Stateroom Check-in, Welcome Dinner AmaLyra On Board the Ship Arrive in Paris, France Fly into Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG) where you will be greeted by your driver who will handle your luggage and transportation to the AmaLyra ship. Board the Ship and Check-in to Your Stateroom Check into your home for the next 8 days and 7 nights—the AmaLyra—and find your luggage has been magically delivered to your stateroom. Welcome Dinner On Board the Ship Meet up with your fellow Adventurers as you toast the beginning of what promises to be an amazing adventure sailing along the beautiful Seine River through the provincial and cosmopolitan towns and cities of France. Paris Departure Begin your voyage along the Seine River with the magnificent “City of Light” lit up against the nighttime sky as a spectacular start to your Adventures by Disney river cruise adventure. -

The Letters of HPB AP Sinnett

Theosophical University Press Online Edition The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett and Other Miscellaneous Letters Transcribed, Compiled, and with an Introduction A. T. Barker Facsimile of the First Edition, 1925; print edition published by Theosophical University Press 1973 (print version also available); electronic edition published 1999. Electronic version ISBN 1-55700-145-6. This edition may be downloaded for off-line viewing without charge. For ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in this electronic version of the text. Contents Compiler's Preface Introduction Specimen of HPB's Handwriting Table of Contents ". It was thy patience that in the waste attended still thy step, and saved MY friend for better days. What cannot patience do. A great design is seldom snatched at once, 'tis PATIENCE heaves it on. ." — K. H. COMPILER'S PREFACE The letters here presented to the reader, written by the Founder of the Theosophical Society between the years 1880-1888, are intended to form a companion volume to the recently published Mahatma Letters, and should be read in conjunction with that work. They have been transcribed direct from the originals and without omission except for the occasional deletion of a name where-ever for obvious reasons it was absolutely necessary to do so. Contrary to the method employed in The Mahatma Letters, the compiler has permitted himself to correct obvious errors of spelling and punctuation, as these were too numerous to ignore, and no useful purpose could be served by leaving them unedited. Here and there in the text a word appears in square brackets. -

The Maria at Honfleur Harbor by George-Pierre Seurat

The Maria at Honfleur Harbor By George-Pierre Seurat Print Facts • Medium: Oil on canvas • Date: 1886 • Size: 20 ¾” X 25” • Location: National Gallery Prague • Period: • Style: Impressionism • Genre: Pointillism • Prounounced (ON-flue) • Seurat spent a summer painting six landscapes at Honfleur Harbor. They, for the most part, convey the idea of peaceful living that Seurat must have been experiencing during the summer vacation in which he created these pieces. In none of the paintings are waves crashing to shore nor is the wind forcefully blowing something. Another strange thing to note is that in none of the Honfleur paintings is there the easily recognizable shape of a human being. Maybe Seurat sees crowds of people as causes of stress and therefore never incorporates them into his Honfleur works. It is possible that this is the reason why there's an innate calmness to the six paintings. Artist Facts • Pronounced (sir-RAH) • Born December 2, 1859 • Seurat was born into a wealthy family in Paris, France. • Seurat died March 29, 1891 at the age of just 31. The cause of his death is unknown, but was possibly diphtheria. His one-year-old son died of the same disease two weeks later. • Seurat attended the École des Beaux-Arts in 1878 and 1879. • Chevreul, who developed the color wheel, taught Seurat that if you studied a color and then closed your eyes you would see the complementary color. This was due to retinal adjustment. He called this the halo effect. Thus, when Seurat painted he often used dots of complementary color. -

ASML Partners with Van Gogh Brabant and Van Gogh Museum Culture - Knowledge - Technology Education

See all press releases & announcements 5 A N N O U N C E M E N T 0 / 1 0 ASML partners with Van Gogh Brabant and Van Gogh Museum Culture - Knowledge - Technology Education V E L D H O V E N , T H E N E T H E R L A N D S , J U L Y 2 , 2 0 1 9 High-tech company ASML enters into long-term partnership with Van Gogh Brabant in Nuenen and the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where Van Gogh's search for color and light meets state-of-the-art technology. "Vincent van Gogh was from Brabant, and was a rebel and an innovator. Light inspired him and it was central to his work, just like it is at ASML," says Peter Wennink, President and CEO of ASML. “This collaboration gives us the opportunity to help connect and preserve the Van Gogh heritage in Amsterdam and Brabant and to share our knowledge with a wider audience. " ‘Vincentre’ Museum Nuenen Vincent van Gogh painted his first masterpiece in Nuenen in 1885: "The Potato Eaters". It was the result of an intensive search for perspective and light that characterizes his Brabant period. By linking Van Gogh’s life story to the innovative Brainport region, ASML and Van Gogh Brabant are able to further enhance the appeal of the region. This collaboration contributes to the realization of the planned extensions to the Vincentre Museum. In addition, ASML will initiate the realization of the ‘Vincent’s Lightlab’ within the expansion of Vincentre Museum. -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002

Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 2002. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 2002 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012200201_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 7 Director's foreword In 2003 the Van Gogh Museum will have been in existence for 30 years. Our museum is thus still a relative newcomer on the international scene. Nonetheless, in this fairly short period, the Van Gogh Museum has established itself as one of the liveliest institutions of its kind, with a growing reputation for its collections, exhibitions and research programmes. The past year has been marked by particular success: the Van Gogh and Gauguin exhibition attracted record numbers of visitors to its Amsterdam venue. And in this Journal we publish our latest acquisitions, including Manet's The jetty at Boulogne-sur-mer, the first important work by this artist to enter any Dutch public collection. By a happy coincidence, our 30th anniversary coincides with the 150th of the birth of Vincent van Gogh. As we approach this milestone it seemed to us a good moment to reflect on the current state of Van Gogh studies. For this issue of the Journal we asked a number of experts to look back on the most significant developments in Van Gogh research since the last major anniversary in 1990, the centenary of the artist's death. Our authors were asked to filter a mass of published material in differing areas, from exhibition publications to writings about fakes and forgeries. To complement this, we also invited a number of specialists to write a short piece on one picture from our collection, an exercise that is intended to evoke the variety and resourcefulness of current writing on Van Gogh. -

Feeling Hot, Cold and Wet and Cold Hot, Feeling Copyright 2003, 2012 John F

Feeling Hot, Cold and Wet Feeling Hot Visual Arts Lessons • Here Come the Clouds • Rain Again? • Favorite Seasons Drama Lessons • Here Comes the Sun • Storms and Sounds • Snow Sculptures Dance and Movement Lessons • Storm Dance • Wind Effects • Hot and Cold Music Lessons • Weather Report • Breezy Chimes • Rain Song Copyright 2003, 2012 John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. May be reproduced for educational and classroom purposes only. Feeling Hot VISU Here Come the Clouds AL AR Creating clouds with tissue paper collage TS Learning Objectives I Express thoughts and ideas about clouds and the experience of making a collage. I Recognize the shapes and colors of clouds and sky. I Build vocabulary related to the sky and to collage. I Use collage glue and tissue paper. I Tear paper into shapes. I Arrange papers, overlapping them and affixing them to a surface. I Create a collage with tissue paper that shows clouds in the sky. Materials 9"x12" heavy drawing or construction paper, sky colors Larger construction paper for mounting finished artwork TIP Newsprint paper to practice tearing Keep your collage to Tissue paper, assorted sky and cloud colors yourself. Allow children to Collage glue Brushes discover their own Preparation expressions without adult examples. Mix collage glue 3 parts white glue with 1 part warm water • Combine in a jar or bottle with a screw-top lid. • Shake until well mixed. • Transfer to plastic containers for children’s use. 281 Experiment with your own tissue paper collage before the activity to become 281 familiar with the process. T START WITH THE ARTS • VSA arts FEELING HOT, COLD AND WET • Here Come the Clouds • TS INCLUDING ALL CHILDREN AR Teach children the American Sign Language signs for “sky” and “cloud,” and AL use the signs throughout the lesson.