The Wyoming Archaeologist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3 – Community Profile

Chapter 3: COMMUNITY PROFILE The Physical Environment, Socio-Economics and History of Fremont County Natural and technological hazards impact citizens, property, the environment and the economy of Fremont County. These hazards expose Fremont County residents, businesses and industries to financial and emotional costs. The risk associated with hazards increases as more people move into areas. This creates a need to develop strategies to reduce risk and loss of lives and property. Identifying risks posed by these hazards, and developing strategies to reduce the impact of a hazard event can assist in protecting life and property of citizens and communities. Physical / Environment Geology Much of Fremont County is made up of the 8,500 square mile Wind River Basin. This basin is typical of other large sedimentary and structural basins in the Rocky Mountain West. These basins were formed during the Laramide Orogeny from 135 to 38 million years ago. Broad belts of folded and faulted mountain ranges surround the basin. These ranges include the Wind River Range on the west, the Washakie Range and Owl Creeks and southern Big Horn Mountains on the north, the Casper Arch on the east, and the Granite Mountains on the south. The center of the basin is occupied by relatively un-deformed rocks of more recent age. Formations of every geologic age exist in Fremont County. These create an environment of enormous geologic complexity and diversity. The geology of Fremont County gives us our topography, mineral resources, many natural hazards and contributes enormously to our cultural heritage. Topography Fremont County is characterized by dramatic elevation changes. -

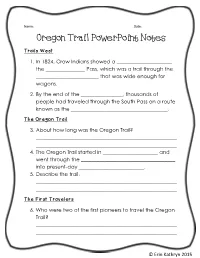

Oregon Trail Powerpoint Notes

Name: _______________________________________________________ Date: ___________________ Oregon Trail PowerPoint Notes Trails West 1. In 1824, Crow Indians showed a _____________________ the _______________ Pass, which was a trail through the ________________________ that was wide enough for wagons. 2. By the end of the ________________, thousands of people had traveled through the South Pass on a route known as the _____________________________________. The Oregon Trail 3. About how long was the Oregon Trail? ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ 4. The Oregon Trail started in _____________________ and went through the ____________________________________ into present-day _________________________. 5. Describe the trail. ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ The First Travelers 6. Who were two of the first pioneers to travel the Oregon Trail? ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ © Erin Kathryn 2015 7. The Whitmans settled in ________________________ and wanted to teach ___________________________________ about _____________________________. 8. Why was Narcissa Whitman important? ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ 9. ____________________________ helped make maps of the Oregon Trail. 10. Fremont wrote ___________________ describing ____________________________________________________. -

Brooks Lake Lodge And/Or Common Brooks Lake Lodge 2

NPS Form 10-900 (7-81) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Brooks Lake Lodge _ _ and/or common Brooks Lake Lodge 2. Location street & number Lower Brooks Lake Shoshone National Forest not for publication city, town Dubois X vicinity of state Wyoming code 056 Fremont code 013 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure X both X work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object _ in process X yes: restricted government scientific X being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Kern M. Hoppe (buildings) United States Forest Service (land) street & number 6053 Nicollet Avenue Region 2 (Mountain Region) Box 25127 city, town Minneapolis, 55419__ vicinity of Lakewood state Colorado 80225 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Dubois Ranger District Shoshone National Forest street & number Box 1S6 city, town Duboi state Wyoming 82513 title Wyoming Survey of Historic Sites has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date 1967; revised 1973 federal _X_ state county local depository for survey records Wyoming Recreation Commission 604 East 25th Street city, town Cheyenne state Wyoming 82002 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site good ruins X altered moved date N/A JLfalr unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Brooks Lake Lodge complex is situated on the western edge of the Shoshone National Forest in northwestern Wyoming, only two miles east of the Continental Divide. -

The Washakie Letters of Willie Ottogary

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 The Washakie Letters of Willie Ottogary Matthew E. Kreitzer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ottogary, W., & Kreitzer, M. E. (2000). The Washakie letters of Willie Ottogary, northwestern Shoshone journalist and leader, 1906-1929. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Washakie Letters of Willie Ottogary Northwestern Shoshone Journalist and Leader 1906–1929 “William Otagary,” photo by Gill, 1921, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution. The Washakie Letters of Willie Ottogary Northwestern Shoshone Journalist and Leader 1906–1929 Edited by Matthew E. Kreitzer Foreword by Barre Toelken Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid free paper 0706050403020100 12345678 Ottogary, Willie. The Washakie letters of Willie Ottogary, northwestern Shoshone journalist and leader, 1906–1929 / [compiled by] Matthew E. Kreitzer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87421-401-7 (pbk.) — ISBN 0-87421-402-5 (hardback) 1. Ottogary, Willie—Correspondence. 2. Shoshoni Indians—Utah—Washakie Indian Reservation—Biography. 3. Indian journalists—Utah—Washakie Indian Reservation—Biography. 4. Shoshoni Indians—Utah—Washakie Indian Reservation—Social conditions. 5. -

Geology of the South Pass Area, Fremont County, Wyoming

Geology of the South Pass Area, Fremont County, Wyoming By RICHARD W. BAYLEY, PAUL DEAN PROCTOR,· and KENT C. CONDIE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 793 Describes the stratigraphy) structure) and metamorphism of the South Pass area) and the iron and gold deposits UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 73-600101 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402- Price $1.10 (paper cover) Stock Number 240l-02398 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract 1 Intrusive igneous rocks-Continued Introduction ------------------------------------- 1 Louis Lake batholith ------------------------ 17 Geography -----------------------·----------- 1 Diabasic gabbro dikes ------------------------ 24 Human his,tory ------------------------------ 2 Structure --------------------------------------- 24 Previous investigations ----·------------------ 3 Metamorphism ----------------------------------- 26 Recent investigations ------------------------ 4 Geochronology ---------------------------------- 28 Acknowledgments ---------------------------- 4 Economic geology -------------------------------- 2~ Geologic setting -------------------------------- 4 Gold ----------·------------------------------ 28 Stratigraphy ------------------------------~---- 6 Quartz veins ---------------------------..:. 29 Goldman Meadows Formation ---------------- 6 -

Red-Desert-Driving-Tour-Map

to the northeast and also marks a crossing of the panorama of desert, buttes, and wild lands. A short South Pass Historical Marker the vistas you see here are remarkably similar to Hikers can remain along the rim or drop down into Honeycomb Buttes historic freight and stage road used to haul supplies walk south reveals the mysterious Pinnacles. The South Pass area of the Red Desert has been a those viewed by thousands of travelers in the past. the basin. Keep an eye out for fossils, raptors, and The Honeycomb Buttes Wilderness Study Area is to South Pass City. See map for recommended hiking human migration pathway for millennia. The crest A side road from the county road will take you to bobcat tracks. one of the most mesmerizing and difficult-to-access access roads for hiking in this wilderness study area. The Jack Morrow Hills several historical markers memorializing South Pass of the Rocky Mountains flattens out onto high-el- landscapes in the Northern Red Desert. These The Great Divide Basin The Jack Morrow Hills, named for a 19th-century evation steppes, allowing easy passage across and the historic trails. Oregon Buttes badlands are made of colorful sedimentary rock crook and homesteader, run north-south between the Continental Divide. Native Americans and their The Oregon Buttes, another wilderness study layers shed from the rising Wind River Mountains As you drive through this central section of the the Oregon Buttes and Steamboat Mountain and ancestors crossed Indian Gap to the south and Whitehorse Creek Overlook area, stand proudly along the Continental Divide, millions of years ago. -

This Type of Cannon, the 1.65" Hotchkiss Mountain Gun. Was Used in the Battles Ot Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1890

! This type of cannon, the 1.65" Hotchkiss Mountain Gun. was used in the Battles ot Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1890. and Bear Paw Mountain. Montana. in 1877. This exalnple. seriai G number 34, manufactured in 1885, is now in the collections of the Wyoming State Museum. ACROSS THE PLAINS 1N 1864 WI1'I-I GEORGE FOEMAN ............ 5 A TraveIer's Account Edited by T. A. Larson INDEPENDENCE ROCK AND DEVIL'S GATE ..................... - .....-............ 23 Robert L. Munkres THE JOHN "PORTUGEE" PHILLIPS LEGENDS, A STUDY IN WYOMING FOLKLORE ............... ........ ......................... ,.........--.. 41 Robert A. Murray POPULFSM IN WYOMING ................................................................ 57 David B. Griffiths BUILDING THE TOWN OF CODY: GEORGE T. BECK, 1894-1943 ........ ............................- .....- ....,,.. .. 73 James D. McLaird POYNT OF ROCKS-SOUTH PASS CITY FREIGHT ROAD TREK .. I07 Trek No. 18 of the Ristoricd Trail Treks Con~piledby Maurine Carley WYOMTNG STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY ...................................... 128 President's Message by Adrian Reynolds Minutes of the Fourteenth Annual Meeting, September 9-10, 1967 BOOK R EVIEM'S Gressley, Thc Anlericnn West: A Reorientation .,...........,..,.......-..-+. 139 Hyde, A Life of George Bent, Written from His htters .................. 140 Kussell, Firmrms, Trrrps & Tools of the Mort~~trrinMen .................. I41 Stands In Timber and Liberty, Cheye~t~~eMemories ..................... ... 542 Karolevitz, Docfo~sof ti~eOld West ...............................................143 -

Resolved Storage Tank Program Contaminated Sites

Resolved Contaminated Tank Sites Facility Facility OwnerN Facility Number Name ame Address City Date Resolved 0-001511 Maverik Country Store #355 Maverik, Inc. 391 Washington Afton 4/9/2018 0-000869 Nield Oil Company (Tire Beau D. Erickson 201 Washington St. Afton 9/14/2016 Factory) 0-000785 Salt River Oil and Motor Rulon D. Horsley 405 Washington Afton 9/14/2016 Company 0-004197 Don Wood Don Wood 611 Washington Street Afton 8/1/2001 0-000862 Bank of Star Valley Bank of Star 384 Washington Street Afton 9/14/2016 Valley Box 226 0-000292 Thomas Drilling Thomas Drilling, 676 North Washington Afton 9/14/2016 Inc. 0-000631 Lincoln County School District Lincoln County 235 East Fourth Afton 9/14/2016 #2 School District #2 0-001815 WY Department of Wyoming U. S. 89 North Afton 9/14/2016 Transportation Department of Transportation 0-003614 Aladdin General Store Historic Aladdin, 1 Rodeo Drive Aladdin 4/25/2013 LLC 0-000123 Alcova Government Camp U.S. Bureau Of Alcova Government Camp Alcova 10/9/1990 Reclamation 0-002201 Sloanes General Store Brian Black 21405 Kortes Road Alcova 1/18/2017 0-002452 Alpine Standard Northstar 120 U. S. Highway 89 Alpine 10/15/2020 Investments, LLC 0-004030 Leavitt Lumber Company Bailey Dotson Greys River Lumber Alpine 8/9/2001 and Gene Vernon Property Mill 0-000627 KJ's Alpine (Former Conrad and 22 West Highway 26 Alpine 6/27/2018 Boardwalk Market) Bischoff, Inc. 0-001048 Little Snake River Valley Carbon County 333 North St. Baggs 3/11/2020 School School Dist. -

California Trail W R O MOUNTAINS H P I S Mount Jefferson Ive S SALMON MONTANA CORVALLIS E R M L E 10497Ft S E L MOUNTAINS a DILLON Orn 25 Er WISC

B DALLAS S La Creole Creek R N E tte S ALEM I N O A B OZEMAN B ILLINGS e Y V r S T. PAUL C om plex m A WALLOWA 90 ive r MINNEAPOLIS 94 T N E R e la Y l N A ello iv M i SALMON RIVER R w sto n e iss U C R issip California Trail W r O M O U N TA IN S H p i S Mount Jefferson ive M S S ALMON MONTANA C OR VALLIS E R L E 10497ft s E L MOUNTAINS A DILLON orn 25 er WISC. te U E B igh iv Designated routes of the E Mary’s River Crossing 3200m u B L H D EA R TO O B R h TH M r California National Historic Trail sc M TS e G e d Riv D B AK ER O ow er G Long Tom River Crossing McC ALL U N P Additional routes T A SOUTH DAKOTA M INNESOTA N A I B B N N I S G S HER IDAN B e 29 90 S A H lle Scale varies in this north-looking EUGENE Jo Fourc he River A BEND h n Da R O perspective view spanning about A y River R Yellowstone O R 35 1,500 miles (2,400 km) from east N C loud Peak PIER R E B orah Peak Lake K to west. Topography derives from Pleasant 5 13187ft R R 12662ft A C ODY GREYBULL M GTOPO30 digital elevation data. -

SHF Flight Hazard

!( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ !( ^_ ^_ 2021 Aviati^_on Hazard Map ^_ !( SHOSHONE NATIONAL FOREST 110°0'0"W ^_ 109°0'0"W ^_ 108°0'0"W ^_ Joliet ^_ !(R Edgar Fromberg ^_ Roberts Roscoe ^_ Fort Smith 5U7 ^_ ^_ ^_q® Bridger 6S1 !( q®^_ ^_ Red Lodge RED Custer Gallatin q®^_ !( Belfry Custer Gallatin !( National Forest Q !( ^_ !( National Forest !(P Jardine ^_ !( !( Gardiner !( Cooke City 45°0'0"N ^_ Silver Gate ^_ ^_ Frannie 45°0'0"N Mammoth Hot Springs ^_ ^_ !( U68 N Tower Junction Meadow Clark q® a B #0 #0 Deaver Cowley t i Lake io g ^_ ^_ n H POY ^_ ^_ a o l r Lovell F n q® o #0 re à ^_ s ^_ Æp Byron t Crandall RS !ep O1 ^_ Dead Powell !( #0 Indian !( #0 ^_ Canyon ^_ Æà !e Yellowstone Sunlight National Park RS ^_ IR-473 #0 #0 !( Fishing Bridge #0 ^_ Cody GEY ^_ COD Greybq®ull !e q® ^_ Burlington Æà ^_ Wapiti Basin West Thumb Clayton MTN RS !(O ^_ #0 ^_ #0 N !( !(M1 !(M Manderson ^_ p !( #0 #0 !( Carter MTN !(SA #0 Meeteetse Æà ^_ South !(SB Fork #0 RS Wood#0 Ridge SC ^_ !( Worland ^_ 44°0'0"N #0 WRL SD q® 44°0'0"N !( Grass Creek ^_ Kirby !(SE Hamilton Dome ^_ !( ^_ !( !(SF !( Indian Ridge !( #0 THP Thermopolis Lava MTN q® Moose #0#0 ^_ ^_ Bridger - Teton p National Forest JAC q® SG !( DUB !( Æà Dubois Black MTN Warm q® #0 Springs ^_ !(SH !( IR-499 Wind#y Ridge 0 SI !( Copper MTN ^_ !(SJ #0 !e #0 !(SK #0 !( Shoshoni Pavillion ^_ ^_ !( !(SL RIW q® !(SN !(SM Riverton !( Ethete W Fort Washakie ^_ ^_ 43°0'0"N in à A d !^_ #0 g 43°0'0"N e R Fort Washakie Helibase n iv c e y r Hudson ^_ Bridger Teton Pinedale National Forest ^_ Lander LND ^_q® PNA Cyclone Pass M q® #0 Medical Facility Information: 5/28/2013 Map Note: Localized areas of turbulant winds exist ^_ Latitude throughout the Shoshone National Forest City, State Hospital Frequency Phone Helipad Location and on adjacent lands. -

Riverton Railroad Depot National Register Form Size

rmNo. 10-300 ^ \Q-i* UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Riverton 4-CMWl Railroad Depot AND/OR COMMON Riverton Depot LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 1st and Main _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Ri verton __ VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Wyoming 56 Fremont 013 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT APUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Fremont County STREET & NUMBER Fremont County Courthouse CITY, TOWN STATE Lander _ VICINITY OF Wyoming 82520 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Fremont County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Lander Wyoming 82520 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Wyoming Recreation Commission Survey of Historic Sites, Markers and Monuments DATE 1967 (revised 1973) —FEDERAL _KSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Wyoming Recreation Commission, 604 East 25th Street CITY. TOWN STATE Cheyenne Wyoming 82002 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _X EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS A ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED The Riverton Depot is situated on the east side of, and parallels, the Chicago and North Western Railroad tracks that intersect the town of Riverton from north to south. A small park is adjacent to the depot on the north, and directly east of the depot is a large parking lot. -

Wind River Interpretive Plan Size

Wind River Indian Reservation Interpretive Plan for the Eastern Shoshone and the Northern Arapaho photo by Skylight Pictures © Preface This interpretive planning project was initiated through the desire of many to hear, sometimes for the ÀUVWWLPHWKHKLVWRU\RIWKH(DVWHUQ6KRVKRQHDQG1RUWKHUQ$UDSDKRSHRSOHRIWKH:LQG5LYHU,QGLDQ 5HVHUYDWLRQ7KLVSODQDWWHPSWVWRVKDUHDQLPSRUWDQWKLVWRU\LQRUGHUWRJDLQDEURDGHUXQGHUVWDQGLQJRI WKHSDVWDQGSUHVHQWRIWKHVWDWH:LWKWKLVPRUHFRPSUHKHQVLYHXQGHUVWDQGLQJWKRVHZKRFRQWULEXWHGWR WKLVSURMHFWKRSHWKDWDJUHDWHUKLVWRULFDODQGFXOWXUDODZDUHQHVVFDQEHJDLQHG 7KLVSODQUHÁHFWVWKHHIIRUWVRIWKH:\RPLQJ6WDWH+LVWRULF3UHVHUYDWLRQ2IÀFH:\RPLQJ2IÀFHRI7RXULVP DQGWKH:LQG5LYHU,QGLDQ5HVHUYDWLRQ7KH86'$)RUHVW6HUYLFH&HQWHUIRU'HVLJQDQG,QWHUSUHWDWLRQ KHOSHGJXLGHWKHSODQQLQJSURFHVVE\WDNLQJLGHDVDQGVWRULHVDQGWXUQLQJWKHPLQWRZRUGVDQGJUDSKLFV 1875 map portion of Wyoming Territory. Image from the Wyoming State Archives. 7KLVSURMHFWZDVIXQGHGE\JHQHURXVJUDQWVIURPWKH:\RPLQJ&XOWXUDO7UXVW)XQGDQG WKH:\RPLQJ'HSDUWPHQWRI7UDQVSRUWDWLRQ7($/*UDQWSURJUDPDVZHOODVIXQGVIURPWKH :\RPLQJ2IÀFHRI7RXULVPDQGWKH:\RPLQJ6WDWH+LVWRULF3UHVHUYDWLRQ2IÀFH$GGLWLRQDOO\ FRXQWOHVVKRXUVZHUHGRQDWHGWRWKHSURMHFWE\6KRVKRQHDQG$UDSDKRWULEDOPHPEHUV 7KHSRLQWVRIYLHZH[SUHVVHGLQWKLVGRFXPHQWDUHSUHVHQWHGIURPWKHLQGLYLGXDOSHUVSHFWLYHVRIWKH(DVWHUQ6KRVKRQHDQG 1RUWKHUQ$UDSDKRWULEHV(DFKWULEHKDVLWVRZQSHUVSHFWLYHVWKDWUHSUHVHQWLWVRZQKLVWRU\DQGHDFKWULEHVSRNHRQO\RQLWVRZQ EHKDOI7KHYLHZVH[SUHVVHGE\WKH(DVWHUQ6KRVKRQHDUHQRWQHFHVVDULO\WKHYLHZVH[SUHVVHGE\WKH1RUWKHUQ$UDSDKRDQGYLFH YHUVD7KHVHYLHZVGRQRWQHFHVVDULO\UHSUHVHQWWKHYLHZVRIWKH6WDWHRI:\RPLQJ