Capital and Identity in Motion in Faulkner's the Sound And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Identity in the Stories of Taylor and O'connor

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1986 From the Country to the City: Southern Identity in the Stories of Taylor and O'Connor Catherine Anne Clark College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Catherine Anne, "From the Country to the City: Southern Identity in the Stories of Taylor and O'Connor" (1986). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625353. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-wxw1-dg89 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE COUNTRY TO THE CITY: SOUTHERN IDENTITY IN THE STORIES OF TAYLOR AND O'CONNOR A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Catherine Anne Clark 1986 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts C J t t d 0 A K j V U /A m a a I . Catherine. Anne Clark Approved, August 1986 Susan Donaldson Walter Wenska Conlee ii DEDICATION To my mother and father who have taught me the most important of my lessons "And if I have the gift of prophecy, and know all mysteries and all knowledge; and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing." — I Corinthians 13:2 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................. -

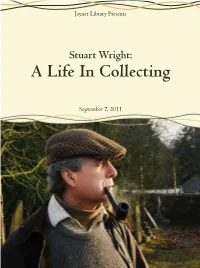

Stuart Wright Booklet

Joyner Library Presents Stuart Wright: A Life In Collecting September 7, 2011 A Message from the Dean East Carolina University® Like Tom Douglass, I first met Stuart Wright when I stepped off the train with my wife Sue in Ludlow, England—the English country squire waiting for us soon proved to be a Southern Gentleman in exile. In fact, I think this was confirmed the night STUART WRIGHT: Sue prepared “southern fried chicken” and mashed potatoes. Stuart asked for the recipe after his first helping, feasted on the leftovers for several days, and said it The Badger of Old Street stirred memories in him from long ago. On our short visit to 28 Old Street, Stuart showed and told us as much as we could absorb about the extraordinary collection of southern American literature that he hoped would eventually come to East Carolina University and Joyner Library. I was delighted with what I saw and heard and carefully calculated how much space we would need to house the collection if we could agree on price and terms. Being only acquainted with the work of some of the authors like Robert Penn Warren, Randall Jarrell, and Eudora Welty, I could not truly appreciate the importance of the book collection or the exceptional quality of the many boxes of letters, journals, and manuscripts that comprised the collection. Fortunately, Tom Douglass could and he and Stuart spent many hours poring over the materials and discussing their significance while I could only listen in amazement. My amazement and delight have only increased markedly since the collection has come to Joyner Library. -

In the Wake of the Sun: Navigating the Southern Works of Cormac Mccarthy © 2009 by Christopher J

In the Wake of the Sun Navigating the Southern Works of Cormac McCarthy Christopher J. Walsh In the Wake of the Sun In the Wake of the Sun Navigating the Southern Works of Cormac McCarthy Christopher J. Walsh Newfound Press THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE LIBRARIES, KNOXVILLE In the Wake of the Sun: Navigating the Southern Works of Cormac McCarthy © 2009 by Christopher J. Walsh Digital version at www.newfoundpress.utk.edu/pubs/walsh Newfound Press is a digital imprint of the University of Tennessee Libraries. Its publications are available for non-commercial and educational uses, such as research, teaching and private study. The author has licensed the work under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/>. For all other uses, contact: Newfound Press University of Tennessee Libraries 1015 Volunteer Boulevard Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 www.newfoundpress.utk.edu ISBN-13: 978-0-9797292-7-0 ISBN-10: 0-9797292-7-0 Walsh, Christopher J., 1968- In the wake of the sun : navigating the southern works of Cormac McCarthy / by Christopher J. Walsh. Knoxville, Tenn. : Newfound Press, University of Tennessee Libraries, c2009. xxiii, 376 p. : digital, PDF file. Includes bibliographical references (p. [357]-376). 1. McCarthy, Cormac, 1933- -- Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PS3563.C337 Z943 2009 Book and cover design by Jayne Rogers Cover image by Andi Pantz I dedicate this book to my mother, Maureen Lillian Walsh, and to the memory of my father, Peter Anthony Walsh (1934-2000), as their hard work and innumerable sacrifices made all of this possible. -

The Peter Taylor Papers Addition

THE ANDREW NELSON LYTLE ADDITION (MSS. 599) Inventory ARRANGED AND DESCRIBED BY CATHERINE ASHLEY VIA 2005 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS JEAN AND ALEXANDER HEARD LIBRARY VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY 419 21ST Avenue South Nashville, TN 37240 615-322-2807 CONTENTS OF INVENTORY Contents Page # Summary 3 Biographical/Historical Note 4-11 Scope and Content Note 12 List of Series and Subseries 13-15 Series and Subseries Descriptions 16-18 Container List 19-39 2 SUMMARY Size 13 linear ft. Geographic United States Locations Inclusive 1853-1995 Dates Bulk 1961-1992 Dates Languages English Summary The Papers of Andrew Nelson Lytle (1902-1995), author, educator, editor, critic and Vanderbilt University alumnus (B.A. 1925), were acquired in 1998 from Lytle’s son-in-law & literary executor, George Chamberlain. Lytle was a member of the Agrarian literary movement and was close colleagues with Robert Penn Warren, John Crowe Ransom, and Allen Tate. Access No restrictions. Restrictions Copyright Andrew Lytle’s literary executor is his son-in-law, George Chamberlain of Sewanee. His address is: George I. Chamberlain 233 Quintard Road Sewanee, TN 37375 Telephone: 931-598-0532 Stack Manuscripts Locations 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE 1902 Born on December 26, in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, to Robert Logan and Lillie Belle Lytle. 1907 Father buys the Log Cabin at Monteagle, Tennessee. 1916-1920 Enrolls in Sewanee Military Academy as a day student in fall of 1916; attends as boarding student after fall of 1917 when mother buys house in Sewanee; wins the Golden Medal for Scholarship; upon graduation is offered, but refuses an appointment to West Point; travels in France with mother and sister, Polly; writes a letter from France to Sewanee’s headmaster, Major Henry Gass, which is printed in The Little Tiger, the student publication; prepares for admission to Oxford while at the home of Mademoiselle Durieux on the Left Bank in Paris with an English tutor; studies fencing. -

The Novels of Andrew Lytle: a Study in the Artistry of Fiction

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1972 The oN vels of Andrew Lytle: a Study in the Artistry of Fiction. Charles Chester Clark Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Clark, Charles Chester, "The oN vels of Andrew Lytle: a Study in the Artistry of Fiction." (1972). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2199. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2199 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

The Peter Taylor Papers Addition

THE ANDREW NELSON LYTLE PAPERS (MSS. 267) Inventory ARRANGED AND DESCRIBED BY CATHERINE ASHLEY VIA 2005 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS JEAN AND ALEXANDER HEARD LIBRARY VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY 419 21ST Avenue South Nashville, TN 37240 615-322-2807 CONTENTS OF INVENTORY Contents Page # Summary 3 Biographical/Historical Note 4-11 Scope and Content Note 12 List of Series and Subseries 13-14 Series and Subseries Descriptions 15-16 Container List 17-47 2 SUMMARY Size 6 linear ft. Geographic United States Locations Inclusive 1873-1988 Dates Bulk 1920-1960 Dates Languages English Summary The Papers of Andrew Nelson Lytle (1902-1995), author, educator, editor, critic and Vanderbilt University alumnus (B.A. 1925), were acquired from Mr. Lytle in three segments. Lytle was a member of the Agrarian literary movement and was close colleagues with Robert Penn Warren, John Crowe Ransom, and Allen Tate. Access No restrictions. Restrictions Copyright Andrew Lytle’s literary executor is his son-in-law, George Chamberlain of Sewanee. His address is: George I. Chamberlain 233 Quintard Road Sewanee, TN 37375 Telephone: 931-598-0532 Stack Manuscripts Locations 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE 1902 Born on December 26, in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, to Robert Logan and Lillie Belle Lytle. 1907 Father buys the Log Cabin at Monteagle, Tennessee. 1916-1920 Enrolls in Sewanee Military Academy as a day student in fall of 1916; attends as boarding student after fall of 1917 when mother buys house in Sewanee; wins the Golden Medal for Scholarship; upon graduation is offered, but refuses an appointment to West Point; travels in France with mother and sister, Polly; writes a letter from France to Sewanee’s headmaster, Major Henry Gass, which is printed in The Little Tiger, the student publication; prepares for admission to Oxford while at the home of Mademoiselle Durieux on the Left Bank in Paris with an English tutor; studies fencing. -

The Critical Reception of I'll Take My Stand and John

TRADITION, MYTH AND THE AGRARIAN COMMUNITY: THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF I’LL TAKE MY STAND AND JOHN CROWE RANSOM’S AGRARIAN PHILOSOPHY BY MATTHEW ERIC JORDAN (Under the direction of Dr. James E. Kibler) ABSTRACT Seeking to define aspects of John Crowe Ransom’s agrarian philosophy, particularly as it relates to individuals, communities, and the traditions and myths associated with each. While critics dismissed the offering as a sentimentalized eulogy for the fantasy of antebellum culture, Ransom articulated that principles and ideas, those elements addressing the humane life lived in contemplation, were the focus of his contributions to I’ll Take My Stand. This examination presents key criticisms that represent the harshest charges leveled against Ransom, and, in doing so, a context is provided in which the subtleties of the Agrarian philosophy can be contrasted with those of Industrialism. Ultimately, this examination will reveal that Ransom’s philosophical position was dismissively misunderstood at I’ll Take My Stand’s original critical reception. INDEX WORDS: John Crowe Ransom, I’ll Take My Stand, Critical Reception, Agrarianism, Philosophy, Agrarians, Myth, Tradition. TRADITION, MYTH AND THE AGRARIAN COMMUNITY: THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF I’LL TAKE MY STAND AND JOHN CROWE RANSOM’S AGRARIAN PHILOSOPHY by MATTHEW ERIC JORDAN B.A., The University of Georgia, 1997 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2002 2002 Matthew Eric Jordan All Rights Reserved TRADITION, MYTH AND THE AGRARIAN COMMUNITY: THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF I’LL TAKE MY STAND AND JOHN CROWE RANSOM’S AGRARIAN PHILOSOPHY by MATTHEW ERIC JORDAN Approved: Major Professor: James Kibler Committee: Jonathan Evans Carl Rapp Electronic Version Approved: Gordhan L. -

2004–2005 Catalog

COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES CATALOG & ANNOUNCEMENTS 2004–2005 Information contained in this catalog is current as of the date of printing. See <http://sewaneetoday.sewanee.edu/catalog/> for most recent revisions. Assembled by the Office of Communications 134_CAS_catalog_0404.indd 1 7/7/04 3:52:49 PM SEWANEE: THE UNIVERSITY OF THE SOUTH The University of the South does not discriminate in employment, the admission of students, or in the administration of any of its educational policies, programs, or activities on the basis of race, color, national or ethnic origin, sex, sexual orientation, age, disability, veteran/re- serve/national guard status, or religion (except in the School of Theology’s Master of Divinity program, where preference is given to individuals of the Episcopal faith and except for those employment positions where religious affiliation is a necessary qualification). The University of the South complies with the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972, the I.R.S. Anti-Bias Regulation, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Americans with Disabilities Act. The Provost of the University of the South, Ms. Linda Bright Lankewicz, 735 University Avenue, Sewanee, TN, 37383-1000, 931-598-1000, is the person responsible for coordinating the university’s effort to comply with these laws. LEGAL TITLE OF THE UNIVERSITY “The University of the South” This catalog provides information which is subject to change at the discretion of the College of Arts and Sciences. It does not constitute any form of a contractual agreement with current or prospective students or any other person. -

Who Were the 'Nashville Agrarians'?

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 11, Number 1-2, Winter-Spring 2002 pre-Raphaelites, which explicitly called for a return to pre-Renaissance, feudal culture and political organiza- tion. Various cults and secret orders, claiming to be mod- elled on pagan mysticism, were formed, or re-invigorat- Who Were the ed, including Theosophy, Rosicrucianism, and Freema- sonry’s “Order of the Golden Dawn.” Each of these was ‘Nashville Agrarians’? but a re-packaging of the idea of the especially privileged, he overtly fascist, pro-Confederate, pro-slav- whether called “Elect,” “Adepts,” “Ascended Masters,” ery, pro-Ku Klux Klan “Nashville Agrarian” “Magi,” or “Little Green Men.” These cults became the T movement was founded and led by a small group inspiration for a dizzying assortment of schools of litera- of poets and literary critics grouped around The ture, music, dance, philosophy, and psychology. What Fugitive magazine, who, when fascism became “conspiracy theorists” see as secret plots and disguised unfashionable, went on to found the literary move- intentions, is actually much more insidious. Much as ment, known as “The New Criticism,” which has occurred with the succeeding “counterculture” of the last dominated American literary education since the third of the Twentieth century, the Euro-American 1930’s. The idea of “The New Criticism” is, that the “intellectual” elite was largely, and quite openly, mired role of all art is to focus human thinking away from in the extended social relations of this shifting pattern of big ideas and toward those sensual concerns which cult associations. The essential features of “Little Green humans share with the beasts. -

JONES, MADISON, 1925- Madison Jones Papers, 1950-1989

JONES, MADISON, 1925- Madison Jones papers, 1950-1989 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Jones, Madison, 1925- Title: Madison Jones papers, 1950-1989 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 684 Extent: 6.5 linear ft. (15 boxes) Abstract: Papers of author and educator Madison Jones, including corrected typescripts, manuscript notebooks, and preliminary drafts. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: No reproduction of any unpublished manuscripts, without the written permission of the author. Source Purchase, 1990. Custodial History Floyd C. Watkins American Literary Manuscripts Collection. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Madison Jones papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Barbara J. Mann, August 1990. This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. Please refer to the Rose Library's harmful language statement for more information about why such language may appear Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Madison Jones papers, 1950-1989 Manuscript Collection No. 684 and ongoing efforts to remediate racist, ableist, sexist, homophobic, euphemistic and other oppressive language. If you are concerned about language used in this finding aid, please contact us at [email protected]. Collection Description Biographical Note Madison Percy Jones, Jr. was born March 21, 1925 in Nashville, Tennessee, to Madison Percy and Mary Temple (Webber) Jones. -

Fair and Tender Ladies at Tinker Creek: Women Writers Coming of Age

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Fair and tender ladies at Tinker Creek: Women writers coming of age. Nancy Clyde Parrish College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Parrish, Nancy Clyde, "Fair and tender ladies at Tinker Creek: Women writers coming of age." (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1593092091. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/m2-2q5w-c777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

1 the United States South and Literary Studies During The

THE UNITED STATES SOUTH AND LITERARY STUDIES DURING THE COLD WAR By JORDAN J. DOMINY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Jordan J. Dominy 2 To Jessica Peek Dominy 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Coming from rural Georgia, I speak with an accent that once led a student of mine to interrupt one of my lectures with the question, “I’m sorry, but where are you from?” For this reason and others, I did not see myself writing a dissertation focusing on southern literature. While I enjoyed reading southern authors, as a new graduate student actually researching and writing about them did not cross my mind right away. I suppose subconsciously I worried that if I pursued its study I would become the real-life walking, talking stereotype of the southern scholar, accent and all. However, the community of scholars that I am grateful to be a part of at the University of Florida helped me to see a place where I could make a needed, and what I hope is, a useful intervention in southern studies. I thank my advisor, Susan Hegeman, for being an encouraging and supportive teacher. She provided valuable feedback from our very first conversations about potential dissertation projects and pointed me in the new directions southern studies is taking. Also helpful early in the project was Phillip Wegner, one of my readers, whose seminar first got me thinking a lot about late modernism.