An Efficient Promotion for Ethnic Restaurants. In: EURAM 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taverna Khione Takeout Menu

Taverna Khione Takeout Menu 4pm-7:30 Wednesday-Saturday 25 Mill St Brunswick ME 04011 207-406-2847 Krasi- Our exclusive wines are now available to enjoy at home! Choose a bottle or grab a half case (20% off!) Greek Retsina- $25 bottle Greek Rosé- $25 bottle- $120 mixed half case Greek Sparkling Wine- $35 bottle Greek White Wine- $20 bottle Greek Red Wine- $20 bottle $25 bottle- $120 mixed half case $25 bottle- $120 mixed half case $30 bottle- $144 mixed half case $30 bottle- $144 mixed half case $45 bottle- $216 mixed half case $35 bottle- $168 mixed half case Mezethes- served with housemade village style bread $8 each 8oz Tzatziki- Greek goat yogurt, garlic, dill, cuke Skorthalia – potato, garlic, vinegar, oil Htipiti- feta, grilled hot & sweet pepper Taramosalata- cod roe, lemon, oil, bread Santorini Fava- fava, garlic, vinegar Orektika-Salatas Htapodi Scharas- grilled octopus with Santorini fava, onions and pickled caper leaves 14 Kalamaria- grilled Maine calamari with oregano, lemon and Olympiana Olive Oil 10 Prasopita- baked filo pie with leeks, scallions, dill and feta 10 Kolokytho Keftedes- baked zucchini fritters with feta, mint and Greek yogurt 10 Horiatiki- Greek village salad with tomatoes, cukes, onions, Kalamata olives, sheep’s milk feta 12 Patzaria Salata- roasted beet salad with toasted walnuts and skorthalia 8 Kyrios Piata Arni Paithakia- grilled lamb loin chops with roasted lemon potatoes and grilled zucchini 28 Katsikaki- braised goat with tomato, red wine and herbs; with hilopites pasta and myzithra cheese 26 Xifias- -

Ahi Poke* / 15 Cucumber & Avocado Salad, Ponzu

FROZEN GRASSHOPPER / 15 DRUNKEN MONKEY / 15 CRÈME DE MENTHE, PINNACLE CHOCOLATE VODKA, HAZELNUT LIQUEUR, MALT, BANANA, REESE’S PEANUT BUTTER CUPS, DARK & WHITE CHOCOLATE CRUNCHIES, PEPPERMINT MERINGUE, CHICK-O-STICK, BANANA LAFFY TAFFY, VANILLA FROSTING, MINI PEPPERMINT PATTIES, WINTERGREEN CANDY STICK, REESE’S PIECES VANILLA FROSTING, MINT CHOCOLATE CHIPS A-CHOCOLYPSE NOW / 15 CAMPFIRE SMORES / 15 PINNACLE CHOCOLATE VODKA, CHOCOLATE SAUCE, OREO MARSHMALLOW VODKA, GRAHAM CRACKER, CHOCOLATE SAUCE, COOKIES,FUDGE BROWNIE, MILK CHOCOLATE BAR, CHOCOLATE TOASTED MARSHMALLOW, S’MORES CANDY STICK, S’MORES POCKY STICK, VANILLA FROSTING, DARK CHOCOLATE CRUNCHIES CHOCOLATE BALLS, CHOCOLATE COVERED GRAHAM CRACKERS, VANILLA FROSTING, GRAHAM CRUMBLE THE FAT BOY / 15 CHOCOLATE-KARAMEL VODKA, REESE’S PEANUT BUTTER CUPS, COOKIES & CREAM / 15 PRETZELS, RAINBOW SPRINKLES, FROOT LOOPS, OREO COOKIES, PINNACLE WHIPPED CREAM VODKA, OREO & CHOCOLATE CHIP BUTTERFINGER, CHOCOLATE COVERED PRETZEL STICK, COOKIES, CHOCOLATE CHIP ICE CREAM SANDWICH, DARK & WHITE RAINBOW TWIST POP, COTTON CANDY, VANILLA FROSTING, CHOCOLATE CRUNCHIES, VANILLA FROSTING, OREO CRUMBS MICRO JAWBREAKERS DONUTELLA / 15 PATRON XO CAFE, HAZELNUT CROQUANT, PIROUETTE COOKIE, NUTELLA, CHOCOLATE COFFEE BEANS, NUTELLA GLAZED DONUT SODA POP / 6 MILKSHAKES & MALTS / 9 VIRGIL’S COLUMBIA WORKS DEATH VALLEY VANILLA, CHOCOLATE, STRAWBERRY, BLACK & WHITE, ROOT BEER SARSAPARILLA SOUR APPLE BANANA SPLIT, VEGAN COCONUT RASPBERRY REED’S GINGER JARRITOS ADD MALT OR CHOCOLATE SYRUP BREW GRAPEFRUIT DEATH VALLEY -

Baked Goods Salads Halva Date Shake 7 Chicken Souvlaki Georgie's Gyros

BAKED GOODS flakey cinnamon swirl brioche 5 andros sourdough w/ honey butter 4 olive & pistachio twist danish 8 koulouri w/ taramasalata 6 chocolate halva croissant 6 halvaroons 2.5 olive oil lemon cake 3 2 wood fired pitas 5 CRETAN 14 OLYMPIA 17 olive oil fried eggs & tiny sunny side up eggs w/ fries cretan sausages & herbs & georgie’s gyro OBVI AVO TOAST 16 feta, dill, allepo pepper STRAPATSATHA 15 BAKED FETA & EGGS 17 a traditional scramble of santorini tomatoes, village farm eggs & tomatoes w/ feta bread & olives TSOUREKI FRENCH TOAST 15 cinnamon butter, tahini honey ANDROS GRANOLA 14 IKARIA 15 heaven’s honey, skotidakis egg whites, slow cooked yogurt & fruit zucchini, otv tomatoes & dill choice of 3 spreads, served w/ crudite, cheese & olives, 32 char grilled kalamaki & 2 wood fired pitas traditional tatziki 9 charred eggplant 9 CHICKEN SOUVLAKI 17 spicy whipped feta 9 GEORGIE’S GYROS 22 taramasalata 9 served on a wood fired pita w/ tomatoes, cucumber, spiced tiny cretan sausages 9 yogurt & a few fries ADD EGG 3 zucchini chips 14 char grilled kalamaki 12 crispy kataifi cheese pie 14 SALADS greek fries add feta 3 add egg 3 9 GREEN GODDESS 11 gyro 8 13 ADD chicken 6 BEETS & FETA PROTEIN octo 14 THE ANDROS 13/18 FULL COFFEE FROM LA COLOMBE COFFEE midas touch 14 french press 4/7 santorini bloody 12 espresso 3 olive martini 14 cappuccino 4 harmonia spritz 13 espresso freddo 4.5 ZERO beet it 10 7 cappuccino freddo 5 HALVA DATE SHAKE grove & tonic 11 almond freddo 5 almond, banana, cinnamon, panoma 10 honey, oatmilk JUICE FROM REAL GOOD STUFF CO. -

Taverna by Michael Psilakis

MP TAVERNA BY MICHAEL PSILAKIS MEZE SOUVLAKI PITA, TZATZIKI, ONION, TOMATO, ROMAINE, BELL PEPPER BARREL AGED FETA 15 HOUSE SMASHED FRIES greek olives, dolmas, pita FALAFEL SOUVLAKI 17 OCTOPUS 23 bulgar wheat, lentil & chick pea croquette mediterranean chick pea salad, greek yogurt AGED GREEK SAUSAGE 16 PORK TENDERLOIN 18 pork shoulder, leek & orange AMISH CHICKEN SOUVLAKI 18 CYPRIOT LAMB SAUSAGE 16 SEFTALIA SOUVLAKI 18 tzatziki, grilled pita cypriot lamb sausage MEATBALLS 15 LOUKANIKO SOUVLAKI 18 olives, garlic confit, tomato cured pork sausage SHRIMP SANTORINI 17 BLACK ANGUS HANGER STEAK SOUVLAKI 22 baked in tomato sauce & topped with barrel aged feta SIGNATURE ENTREES DIPS FUSILLI 19 SERVED WITH FLAME GRILLED PITA slow roasted tomato, garlic, feta, basil, calabrian chilies ADD ENGLISH CUCUMBER WEDGES +3 chicken +5, wild ecuadorian shrimp +9 TZATZIKI 15 ROASTED LEMON AMISH CHICKEN 27 yogurt, cucumber, garlic, dill fingerling potatoes, dill, garlic, white wine HUMMUS 13 GRILLED BRANZINO 32 sundried tomato, garlic, basil roasted cherry tomato, greek olive and warm COMBO 20 fingerling potato salad, lemon, evoo tzatziki & hummus BLACK ANGUS HANGER STEAK & GREEK SAUSAGE 29 house smashed fries MIX GRILL 30 amish chicken, pork tenderloin, cypriot sausage, SALAD greek sausage, house smashed fries ADD: falafel +5, amish chicken +6, faroe island salmon +8, wild ecuadorian shrimp +10, hanger steak & sausage +10 MP CHOPPED 14 romaine, bell peppers, onion, cucumbers, olives, tomato, feta SIMPLY GRILLED GREEK VILLAGE 16 CHOICE OF SIDE OR MP CHOPPED -

MGM Casino Proposal for Filos Greek Taverna Express

that’s di"erent. You have a pita instead of tortilla. You have some sort of protein in there with lettuce and tomatoes. And instead of cheddar you have feta cheese.” Giving diners dishes that are similar to foods that they’ve previously enjoyed creates a point of entry to Greek cuisine that can be expanded to include more traditional dishes that incorporate completely unfamil- iar #avors and preparations. They only have to try baked moussaka once (a Grecian “lasagna” made with egg- plant, potatoes, and ground beef covered in béchamel MGM Casino Proposal for sauce, then baked golden), and they will be hooked. “Americans have only been exposed to the tip of the Filos Greek Taverna Express iceberg,” says Konstantine. But he has his own vision for the future. Filos Greek Taverna is a new restaurant in the quaint New England town “I predict that there will be a thousand Greek-Mediterranean restaurants out there in 10 years,” he says. of Northampton, Massachusetts. Filos Greek Taverna is a Limited Liability “American consumers are looking for something di"erent. Well, here’s a classic food that’s been around Corporation, managed by its owners, Konstantine and Sunita Sierros. for thousands of years that’s healthy and #avorful.” This is why I believe my restaurant, Filos Greek Taverna Konstantine Sierros has twenty !ve years of experience managing a Express will be a perfect !t in your new MGM Casino in Spring!eld, Massachusetts. successful boutique Italian restaurant in a similar locale in Southampton, Massachusetts. His love and knowledge of food will make the transition to owning and running a food-court type establishment a natural step. -

Small Plates Entrees

Taverna uses an abundance of local, SMALL PLATES seasonal ingredients to highlight the finest of Hellenic cuisine. Enjoy the WARM OLIVES & FETA citrus / garlic / rosemary 8 warmth and hospitality of Old World TZATZIKI sheep milk yogurt / cucumber / dill / pita 9 Greece as part of our family. TIROKAFTERI crushed Epirus spicy feta spread / hot peppers / Persian cucumbers 9 FRIES feta herb aioli / wild oregano 6 TARAMOSALATA cod roe spread / pickled red onion / crispy potato chips 11 SAGANAKI flamed Kefalograviera / carmelized onions / sunflower seeds / Metaxa 16 OKTAPODAKI Spanish octopus / Santorini fava / ramp almond relish / Aegean capers 15 SALATA local field lettuces / pistachio crusted feta / strawberry rhubarb marmelada 16 SOUPA young carrots / feta mousse / Medjool dates / cocoa nib coffee crumble 15 HORTA steamed greens / garlic / Calabrian chili / lemon 9 TAVERNA SOUVLAKI Llano Seco pork / slab bacon / charred lemon / mustard seeds 17 ENTREES TAVERNA GYRO chef’s daily choice of meat / tzatziki / patata / pita 19 OMELETA farm egg omelette / Epirus feta / foraged mushrooms / avocado 18 KOTOPOULAKI crispy chicken salad / phyllo & sesame / little gems / beets / honey mustard 24 FASOLADA braised gigantes / broccolini / melitzana / charred halloumi / sprouted hemp 23 PSARAKI Mt Lassen trout / chilled orzo pilafi / wild rocket greens / green goddess 32 TAVERNA BIFTEKI Bassian Farms steak burger / kasseri cheese / fries 22 ARNAKI grilled Superior Farms lamb rib chop / young onions / crispy potatoes 27 Every day is a gift. A 5% Living Wage surcharge will be added to all purchases. 100% of this surcharge is used to support living wages for η κάθε μέρα είναι δώρο all TAVERNA employees. A 20% gratuity will be added to all parties of 6 or more. -

We Produce the Unique Flavor Real Turkish Delight of Unforgettable Moments, Özdilek Lokum, for You

Real Turkish Delight We produce the unique flavor Real Turkish Delight of unforgettable moments, Özdilek Lokum, for you. One of our traditional flavors dating back to the 15th century, the Turkish delight started to be produced in our facilities in Afyonkarahisar in 1996 with the Özdilek Lokum brand. Produced with different flavors, the traditional handiwork method and devotion, Özdilek Lokum meets its customers in Özdilek hypermarkets. And the special boutique products prepared by the Özdilek Holding Food R&D unit are presented to the customers in Özdilek Turkish Delight stores in Özdilek Bursa and ÖzdilekPark İstanbul ÖZDİLEK LOKUM WICK SERIES Wits its orange and pomegranate flavored varieties, Özdilek Lokum turns the Turkish delight into a fresh sweet and offers a kadayif and pistachio dipped wick Turkish delight for those looking for a more traditional flavor. As well as the plain pistachio that offers you pistachio’s harmony with the Turkish delight, you can also choose the milk pistachio wick Turkish delight for its smooth and milky taste. ORANGE PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT | POMEGRANATE PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT PLAIN PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT | MILK PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT KADAYIF PISTACHIO TURKISH DELIGHT ÖZDİLEK LOKUM HONEY SERIES Özdilek Lokum honey series, prepared with honey, which is considered as a remedy from past to present, have the feeling of the Ottoman court kitchen. Özdilek honey Turkish delights offer a unique delicacy, appealing to all tastes with hazelnut, almond and pistachio kadayif varieties. Freshly produced, Özdilek Turkish delights will enrich your presentations with five various series! HAZELNUT-DIPPED HONEY & HAZELNUT TURKISH DELIGHT HONEY ALMOND TURKISH DELIGHT HONEY, PISTACHIO & KADAYIF TURKISH DELIGHT ÖZDİLEK LOKUM SQUARE CLASSICS SERIES Classic Turkish delight series, the favorite of those who prefer simpler flavors, offer alternatives as rose & biscuit, lemon and mint. -

Tören Yemeklerġnġn Bġlġnġrlġğġ Üzerġne Kuġaklar Arasindakġ Farkliliklarin Belġrlenmesġne Yönelġk Bġr Araġti

TÖREN YEMEKLERĠNĠN BĠLĠNĠRLĠĞĠ ÜZERĠNE KUġAKLAR ARASINDAKĠ FARKLILIKLARIN BELĠRLENMESĠNE YÖNELĠK BĠR ARAġTIRMA: AFYONKARAHĠSAR ĠLĠ ÖRNEĞĠ Nazmiye ÇĠFTÇĠ Yüksek Lisans Tezi DanıĢman: Dr.öğr.Üyesi Asuman PEKYAMAN Haziran, 2019 Afyonkarahisar T.C. AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ TURĠZM ĠġLETMECĠLĠĞĠ ANABĠLĠM DALI YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ TÖREN YEMEKLERĠNĠN BĠLĠNĠRLĠĞĠ ÜZERĠNE KUġAKLAR ARASINDAKĠ FARKLILIKLARIN BELĠRLENMESĠNE YÖNELĠK BĠR ARAġTIRMA: AFYONKARAHĠSAR ĠLĠ ÖRNEĞĠ Hazırlayan Nazmiye ÇĠFTÇĠ DanıĢman Dr.Öğr.Üyesi Asuman PEKYAMAN AFYONKARAHĠSAR-2019 YEMĠN METNĠ Yüksek Lisans tezi olarak sunduğum „‟Tören Yemeklerinin Bilinirliği Üzerine KuĢaklar Arasındaki Farklılıkların Belirlenmesine Yönelik Bir AraĢtırma: Afyonkarahisar Ġli Örneği” adlı çalıĢmanın, tarafımdan bilimsel ahlak ve geleneklere aykırı düĢecek bir yardıma baĢvurmaksızın yazıldığını ve yararlandığım eserlerin Kaynakça‟da gösterilen eserlerden oluĢtuğunu, bunlara atıf yapılarak yararlanmıĢ olduğumu belirtir ve bunu onurumla doğrularım. 14.05.2019 Nazmiye ÇĠFTÇĠ ii TEZ JÜRĠSĠ KARARI VE ENSTĠTÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜ ONAYI iii ÖZET TÖREN YEMEKLERĠNĠN BĠLĠNĠRLĠĞĠ ÜZERĠNE KUġAKLAR ARASINDAKĠ FARKLILIKLARIN BELĠRLENMESĠNE YÖNELĠK BĠR ARAġTIRMA: AFYONKARAHĠSAR ĠLĠ ÖRNEĞĠ Nazmiye ÇĠFTÇĠ AFYON KOCATEPE ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ TURĠZM ĠġLETMECĠLĠĞĠ ANABĠLĠM DALI Haziran 2019 DanıĢman: Dr.Öğr.Üyesi Asuman PEKYAMAN Zengin mutfak kültürüne ve yemek çeĢitliliğine sahip Afyonkarahisar‟da sürdürülen geleneğin bir parçası olarak doğum, ölüm, sünnet, evlilik gibi özel günlerde -

If You Deconstruct Greece, You Will in the End See an Olive Tree, a Grapevine, and a Boat Remain

a If you deconstruct Greece, you will in the end see an olive tree, a grapevine, and a boat remain. That is, with as much, you reconstruct her. b a Cold appetizers b a Salads b pita bread or bread & dip 3 . Greek salad 9 . tzatziki spread 7 . fresh salad, cherry tomatoes, crouton, grated feta 12 . eggplant spread 8 . rocket , cherry tomates, red peppers, cheeseball 12 . spicy feta cheese spread 8 . fresh salad, figs, strawberries, pistachio, cheese 14 . white “tarama” (fish egg roe) spread 7 . fresh salad, sauted peach, haloumi, nuts 14 . garlic spread (skordalia) 7 . shrimp’s caesar salad 18 . fish “pastourmas” 15 . marinated anchovy’s fillet 10 . a Pasta-Risotto b grilled smoked mackerel 13 . sea food pilaf 18 . octopus in vinegar 15 . traditional Greek pasta with cream & seafood 19 . smoked eel 18 . pasta with eggplant & peppers 13 . pickled eggplant 13 . sea food pasta with Santorinian cherry tomat0es 20 . pasta with smoked eel and fresh rocket 22 . a Hot appetizers b Crab pasta for 2 persons 42 . steamed mussels 12 . fried mussels 17 . ‘saganaki” mussels 17 . a Main dishes b fried calamari 11 . sea catch of the day …. grilled 75 per kg grilled octopus 16 . grilled lobster or with pasta 100 per kg shrimp’s “saganaki” (2 kinds) 19 . fresh tuna fillet grilled 24 . Scallops in garlic butter 18 . grilled prawns 24 . Red mullet ceviche 18 . calamari with cream ‘n cheece 18 . grilled feta cheese 8 . fresh grilled sardines 13 . Naxo’s “graviera saganaki” 9 . fresh fish fillet a la “Armeni” 22 . grilled haloumi cheese 9 . monkfish as you wish 18 . -

Herald for Sept. Alan 2008 Copy.Indd

Saint Sophia HERALD Volume 13 Number 9 Many Lives...One Heart September, 2008 “What’s That Around Your Neck?” I was privileged to have spent almost two weeks in Greece this summer where I had the pleasant task of baptizing the granddaughter of a very dear friend. Greece is the premier laboratory of western history and civilization. Whatever period of time or era one wishes to examine, it is all there. For Christians who study the New Testament scriptures, there is no better place to walk in the footsteps of St. Paul than Greece. On Sunday, August 3rd, I took the commuter train from Kifissia, a northern suburb of Athens, to go to Monastiraki, the closest station to the ancient Athenian agora or market place just under the shadow of the Acropolis. I wanted to walk through the ancient city ruins and end up on Mars Hill, known in the book of Acts, Chapter 17 as the Areopagus. It is a small rocky hill where St. Paul stood and addressed the Athenian philosophers and skeptics, preaching to them the gospel message of Jesus Christ. I wanted to stand where Paul stood nearly 2000 years before and to vicariously sense through my spiritual imagination, a little of what he saw and experienced. The train was packed…standing room only. A few feet away from me stood a young man who was intently looking at me. At ev- ery station stop he inched his way closer to me. Half way into the 30 minute ride to downtown Athens, we were almost face to face. -

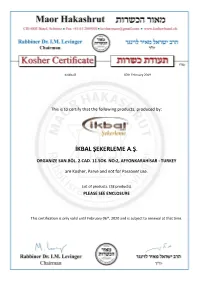

Ikbal Şekerleme A.Ş

Koikbal3 07th February 2019 This is to certify that the following products, produced by: İKBAL ŞEKERLEME A.Ş. ORGANİZE SAN.BÖL. 2.CAD. 11.SOK. NO:2, AFYONKARAHİSAR - TURKEY are Kosher, Parve and not for Passover use. List of products: (38 products) PLEASE SEE ENCLOSURE This certification is only valid until February 06th, 2020 and is subject to renewal at that time. ENCLOSURE LIST OF THE PRODUCTS of İKBAL ŞEKERLEME A.Ş. ORGANİZE SAN.BÖL. 2.CAD. 11.SOK. NO:2, AFYONKARAHİSAR - TURKEY INCLUDED IN THE KOSHER - CERTIFICATE OF 07/02/2019 1. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH TURKISH COFFEE AND PISTACHIO (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 2. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED ASSORTED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH COCONUT) (PISTACHIO-HAZELNUT-ALMOND) 3. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH PISTACHIO (COVERED WITH CHOCOLATE) 4. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH PISTACHIO (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 5. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED PASHA TURKISH DELIGHT WITH PISTACHIO 6. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED PRINCESS TURKISH DELIGHT WITH HAZELNUT 7. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH EXTRA RICH PISTACHIO 8. TRADITIONAL DOUBLE ROASTED TURKISH DELIGHT WITH PISTACHIO (COVERED WITH COCONUT) 9. TRADITIONAL TURKISH DELIGHT COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR 10. TRADITIONAL SMALL CUT ASSORTED FRUIT FLAVOURED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR), (KIWI - LEMON - ORANGE - BANANA - STRAWBERRY) 11. TRADITIONAL SMALL CUT ASSORTED FRUIT FLAVOURED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH COCONUT) 12. TURKISH DELIGHT WITH FRUIT FLAVOUR & MIX NUTS COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR 13. TRADITIONAL ROSE - LEMON - ORANGE FLAVORED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 14. TRADITIONAL TURKISH DELIGHT WITH GUM MASTIC (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 15. TRADITIONAL ROSE FLAVORED TURKISH DELIGHT (COVERED WITH ICING SUGAR) 16. -

Taramasalata and Babaganoush by Dariush Lolaiy

TARAMASALATA AND BABAGANOUSH BY DARIUSH LOLAIY BABAGANOUSH INGREDIENTS: Three large ripe eggplants 1/4 t salt 100ml olive oil handful chopped parsley Juice of 1/2 a lemon 2 Tbsp. tahini 4 pita breads METHOD: Using a hot element or BBQ grill, cook the whole eggplants until the skin is burned and crispy. Turn as the skin begins crackle and burn while cooking. When the flesh has become soft, cut the eggplants in half lengthways and spread them open, watch your fingers with the hot steam. Scrape out the flesh, discard the skins then chop the flesh roughly on a chopping board, sprinkle with salt and drizzle a small amount of olive oil, pop the parsley on top and roughly chop to mix it with the eggplant, as you chop squeeze in the lemon juice. Transfer from the chopping board into a mixing bowl and add the tahini and while mixing, drizzle in the remaining olive oil. To serve, chargrill the pita bread, slice it into quarters and serve with the warm babaganoush. 1 © Adrenalin Ltd. www.whanauliving.co.nz TARAMASALATA INGREDIENTS: 1/2 tin chickpeas, drained 1 Tbsp. olive oil 1/4 tsp. smoked paprika 1/4 tsp. salt 1/2 small garlic clove 1/4 white onion chopped 3 slices white bread, crusts removed cut into rough pieces 100g salted fish roe 40ml water 100ml vegetable oil squeeze of lemon juice Pinch of salt to season. METHOD: Drain and toss the chickpeas in olive oil, smoked paprika and salt, lay on an oven tray and roast in a 130° oven for one hour until they become dry.