One Country, Two Systems" in Practice : an Analysis of Six Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

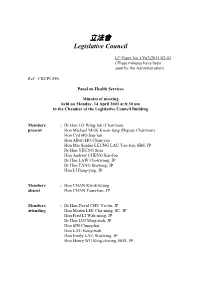

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)2011/02-03 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/HS Panel on Health Services Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 14 April 2003 at 8:30 am in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Dr Hon LO Wing-lok (Chairman) present Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung (Deputy Chairman) Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, SBS, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Dr Hon LAW Chi-kwong, JP Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP Hon LI Fung-ying, JP Members : Hon CHAN Kwok-keung absent Hon CHAN Yuen-han, JP Members : Dr Hon David CHU Yu-lin, JP attending Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP Hon SIN Chung-kai Hon LAU Kong-wah Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Henry WU King-cheong, BBS, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Mr Thomas YIU, JP attending Deputy Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Mr Nicholas CHAN Assistant Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Dr P Y LAM, JP Deputy Director of Health Dr W M KO, JP Director (Professional Services & Public Affairs) Hospital Authority Dr Thomas TSANG Consultant Clerk in : Ms Doris CHAN attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2) 4 Staff in : Ms Joanne MAK attendance Senior Assistant Secretary (2) 2 I. Confirmation of minutes (LC Paper No. CB(2)1735/02-03) The minutes of the regular meeting on 10 March 2003 were confirmed. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

APRES Moi LE DELUGE"? JUDICIAL Review in HONG KONG SINCE BRITAIN RELINQUISHED SOVEREIGNTY

"APRES MoI LE DELUGE"? JUDICIAL REvIEw IN HONG KONG SINCE BRITAIN RELINQUISHED SOVEREIGNTY Tahirih V. Lee* INTRODUCTION One of the burning questions stemming from China's promise that the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) would enjoy a "high degree of autonomy" is whether the HKSAR's courts would have the authority to review issues of constitutional magnitude and, if so, whether their decisions on these issues would stand free of interference by the People's Republic of China (PRC). The Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 promulgated in PRC law and international law a guaranty that implied a positive answer to this question: "the judicial system previously practised in Hong Kong shall be maintained except for those changes consequent upon the vesting in the courts of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the power of final adjudication."' The PRC further promised in the Joint Declaration that the "Uludicial power" that was to "be vested in the courts" of the SAR was to be exercised "independently and free from any interference."2 The only limit upon the discretion of judicial decisions mentioned in the Joint Declaration was "the laws of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and [to a lesser extent] precedents in other common law jurisdictions."3 Despite these promises, however, most of the academic and popular discussion about Hong Kong's judiciary in the United States, and much of it in Hong Kong, during the several years leading up to the reversion to Chinese sovereignty, revolved around a fear about its decline after the reversion.4 The * Associate Professor of Law, Florida State University College of Law. -

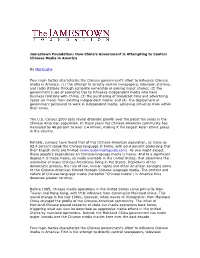

Jamestown Foundation: How China's Government Is Attempting To

Jamestown Foundation: How China’s Government is Attempting to Control Chinese Media in America By Mei Duzhe Four main tactics characterize the Chinese government’s effort to influence Chinese media in America: (1) the attempt to directly control newspapers, television stations, and radio stations through complete ownership or owning major shares; (2) the government’s use of economic ties to influence independent media who have business relations with China; (3) the purchasing of broadcast time and advertising space (or more) from existing independent media; and (4) the deployment of government personnel to work in independent media, achieving influence from within their ranks. The U.S. Census 2000 data reveal dramatic growth over the pa0st ten years in the Chinese American population. In these years the Chinese-American community has increased by 48 percent to over 2.4 million, making it the largest Asian ethnic group in the country. Notably, surveys have found that of this Chinese-American population, as many as 82.9 percent speak the Chinese language at home, with 60.4 percent professing that their English skills are limited (www.asianmediaguide.com). As one might expect, these people’s dependence on Chinese-language media is heavy. And to a significant degree it is these media, as made available in the United States, that determine the worldview of many Chinese-Americans living in the States. Depictions of the democratic process, the rule of law, human rights and other American concepts come to the Chinese-American filtered through Chinese-language media. The content and nature of Chinese-language media (hereafter “Chinese media”) in America thus deserves greater scrutiny. -

立法會 Legislative Council

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)280/00-01 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/BC/13/00 Legislative Council Bills Committee on Chief Executive Election Bill Minutes of the tenth meeting held on Thursday, 31 May 2001 at 8:30 am in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon IP Kwok-him, JP (Chairman) Present Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, JP Hon David CHU Yu-lin Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon NG Leung-sing Prof Hon NG Ching-fai Hon Margaret NG Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong Hon HUI Cheung-ching Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong Hon Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, JP Hon Howard YOUNG, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon Ambrose LAU Hon-chuen, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon CHOY So-yuk Hon SZETO Wah Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, SBS, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon LEUNG Fu-wah, MH, JP Hon LAU Ping-cheung Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Members: Hon Andrew WONG Wang-fat, JP (Deputy Chairman) Absent Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, JP Hon Eric LI Ka-cheung, JP - 2 - Hon CHAN Yuen-han Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, JP Dr Hon LO Wing-lok Public Officers : Mr Michael M Y SUEN, GBS, JP Attending Secretary for Constitutional Affairs Mr Robin IP Deputy Secretary for Constitutional Affairs Ms Doris HO Principal Assistant Secretary for Constitutional Affairs Mr Bassanio SO Principal Assistant Secretary for Constitutional Affairs Mr James O'NEIL Deputy Solicitor General (Constitutional) Mr Gilbert MO Deputy Law Draftsman (Bilingual Drafting & Administration) Ms Phyllis KO Senior Assistant Law Draftsman Clerk in : Mrs Percy MA Attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2)3 Staff in : Mr Stephen LAM Attendance Assistant Legal Adviser 4 Mr Paul WOO Senior Assistant Secretary (2)3 - 3 - Action Column I. -

The Brookings Institution Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES The 2004 Legislative Council Elections and Implications for U.S. Policy toward Hong Kong Wednesday, September 15, 2004 Introduction: RICHARD BUSH Director, Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies The Brookings Institution Presenter: SONNY LO SHIU-HING Associate Professor of Political Science University of Waterloo Discussant: ELLEN BORK Deputy Director Project for the New American Century [TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM A TAPE RECORDING.] THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES 1775 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, D.C. 20036 202-797-6307 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. BUSH: [In progress] I've long thought that politically Hong Kong plays a very important role in the Chinese political system because it can be, I think, a test bed, or a place to experiment on different political forums on how to run large Chinese cities in an open, competitive, and accountable way. So how Hong Kong's political development proceeds is very important for some larger and very significant issues for the Chinese political system as a whole, and therefore the debate over democratization in Hong Kong is one that has significance that reaches much beyond the rights and political participation of the people there. The election that occurred last Sunday is a kind of punctuation mark in that larger debate over democratization, and we're very pleased to have two very qualified people to talk to us today. The first is Professor Sonny Lo Shiu-hing, who has just joined the faculty of the University of Waterloo in Canada. -

August 2011 in Hong Kong 31.8.2011 / No 92

August 2011 in Hong Kong 31.8.2011 / No 92 A condensed press review prepared by the Consulate General of Switzerland in HK Economy + Finance Vice-Premier boosts HK role as yuan trade hub: Vice-Premier Li Keqiang announced a raft of more than 30 measures to boost the local economy by encouraging two-way investment and trade between Hong Kong and the mainland and strengthening the city's role in the internationalisation of the yuan. The business community and trade organisations generally welcomed Li's proposals, made on a visit to HK, hoping they would improve gloomy market sentiment. Of the measures he announced at a forum on the nation's 12th five- year plan, 12 are related to financial services and the development of the offshore yuan market. One key scheme to support the stock market is to allow mainland investors to invest in HK stocks by launching the long-awaited index-tracking Exchange Traded Fund backed by a portfolio of HK stocks. The fund, to be listed on the stock exchanges in Shenzhen or Shanghai, will allow mainlanders to invest in Hong Kong stocks. Several other measures will encourage expanded use of the yuan. One is a 20 billion yuan (HK$24.4 billion) quota for HK companies to invest in securities on the mainland via a yuan-denominated Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII) scheme. This could help achieve a better return for the 554 billion in yuan now sitting as low-yielding deposits in banks in HK. A scheme allowing companies to settle trades in yuan, currently limited to 20 provinces, is being expanded nationwide. -

Research Study on the Agreement Between Hong Kong and the Mainland Concerning Surrender of Fugitive Offenders

RP05/00-01 Research Study on the Agreement between Hong Kong and the Mainland concerning Surrender of Fugitive Offenders March 2001 Prepared by Mr CHAU Pak-kwan Mr Stephen LAM Research and Library Services Division and Legal Service Division Legislative Council Secretariat 5th Floor, Citibank Tower, 3 Garden Road, Central, Hong Kong Telephone : (852) 2869 7735 Facsimile : (852) 2525 0990 Website : http://www.legco.gov.hk E-mail : [email protected] C O N T E N T S page Executive Summary Introduction 1 Background 1 Scope of Study 1 Chapter 1 -Principles and Approaches in Extradition Treaties Signed 2 by China with Foreign Countries Legal Basis of China’s Extradition System 2 China’s Domestic Legal Norms 2 International Legal Norms 3 Basic Principles and Contents of Sino-Foreign Bilateral Extradition 8 Treaties Basic Principles 8 Basic Contents 9 Extraditable Offences 10 Circumstances under which extradition should be refused 12 Circumstances under which extradition may be refused 14 Principle of Non-extradition for Political Offences 15 Principle of Non-extradition for Death Penalty 21 Chapter 2 -Arrangements for the Surrender of Fugitive Offenders 24 between Hong Kong and Foreign Countries Fugitive Offenders Ordinance 24 Surrender of Fugitive Offenders 24 Persons Liable to be Surrendered 25 Relevant Offences 26 General Restrictions on Surrender 26 Procedural Safeguards 26 Treatment of Persons Surrendered from Prescribed Place 27 Transit 28 Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters 28 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The Legislative Council Secretariat welcomes the re-publication, in part or in whole, of this research report, and also its translation in other languages. Materials may be reproduced freely for non- commercial purposes, provided acknowledgement is made to the Research and Library Services Division of the Legislative Council Secretariat as the source and one copy of the reproduction is sent to the Legislative Council Library. -

Media Freedom in Chinese Hong Kong Richard Cullen City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Global Business & Development Law Journal Volume 11 | Issue 2 Article 3 1-1-1998 Media Freedom in Chinese Hong Kong Richard Cullen City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/globe Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard Cullen, Media Freedom in Chinese Hong Kong, 11 Transnat'l Law. 383 (1998). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/globe/vol11/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Law Reviews at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Global Business & Development Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Article Media Freedom In Chinese Hong Kong Richard Cullen* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................... 384 U. BACKGROUND ............................................... 386 A. The ColonialEra ......................................... 386 B. The TransitionalPeriod ................................... 387 C. Points of Conflict ......................................... 388 III. OVERVIEW OF THE MEDIA IN HONG KONG ......................... 391 IV. THE REGULATORY FRAMEWORK .................................. 396 V. THE JUDICIARY AND THE MEDIA ................................. 399 A. Introduction ............................................. 399 B. The Press in Court ........................................ 402 C. Summary .............................................. -

One Country, Two Legal Systems (Crowley Report)

ONE COUNTRY, TWO LEGAL SYSTEMS? TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................1 A. Overview .....................................................................................................................................3 I. PRESERVING THE RULE OF LAW.............................................................................................4 A. The Rule of Law..........................................................................................................................5 1. General International Standards...............................................................................................5 2. The Sino-British Joint Declaration ..........................................................................................7 B. Implementing International Commitments: Hong Kong and the Basic Law ............................8 C. The Right of Abode Decisions ..................................................................................................10 1. Background ............................................................................................................................10 2. The Court of Final Appeal’s Decisions .................................................................................12 a. Article 158: The Reference Issue......................................................................................12 b. Articles 22 and 24 of the Basic Law..................................................................................15 -

Academic Freedom, Political Interference, and Public Accountability: the Hong Kong Experience Johannes M

Back to Volume Seven Contents Academic Freedom, Political Interference, and Public Accountability: The Hong Kong Experience Johannes M. M. Chan and Douglas Kerr Abstract In 2015, interference with academic freedom dominated public discourse in Hong Kong. This article provides an analysis of academic freedom in Hong Kong, addresses some systemic problems, and engages the debates between academic freedom and accountability of publicly funded institutions. It argues that the interference is not a one-off incident but forms part of a general trend toward a more restrictive regime of control over tertiary institutions in Hong Kong. Protection of academic freedom is of particular importance in such a restrictive political context. From Giordano Bruno, who was burned for preaching the heresy that the Earth was not the center of the universe, to the many unknown scholars tortured for speaking the truth during China’s Cultural Revolution, history is filled with sad pages documenting the suppression of academic freedom. Academic freedom is vulnerable in that academics and academic institutions have little but their own conscience and integrity to rely on in defending it, and that defense is usually at great personal cost. The threat to academic freedom is powerful and disturbing, since when academic freedom is not tolerated, let alone respected, other fundamental freedoms are also likely in peril. The Hong Kong Context This essay documents three cases in which academic freedom was jeopardized, and in one case seriously damaged, in Hong Kong. It is necessary to preface these accounts with a survey of what is at stake in the particular Hong Kong context.