A Re-Interpretation of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police's Handling of the 1931 Estevan Strike and Riot Steven Hewitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Birding Trail Experience (Pdf)

askatchewan has a wealth of birdwatching opportunities ranging from the fall migration of waterfowl to the spring rush of songbirds and shorebirds. It is our hope that this Birding Trail Guide will help you find and enjoy the many birding Slocations in our province. Some of our Birding Trail sites offer you a chance to see endangered species such as Piping Plovers, Sage Grouse, Burrowing Owls, and even the Whooping Crane as it stops over in Saskatchewan during its spring and fall migrations. Saskatchewan is comprised of four distinct eco-zones, from rolling prairie to dense forest. Micro-environments are as varied as the bird-life, ranging from active sand dunes and badlands to marshes and swamps. Over 350 bird species can be found in the province. Southwestern Saskatchewan represents the core of the range of grassland birds like Baird's Sparrow and Sprague's Pipit. The mixed wood boreal forest in northern Saskatchewan supports some of the highest bird species diversity in North America, including Connecticut Warbler and Boreal Chickadee. More than 15 species of shorebirds nest in the province while others stop over briefly en-route to their breeding grounds in Arctic Canada. Chaplin Lake and the Quill Lakes are the two anchor bird watching sites in our province. These sites are conveniently located on Saskatchewan's two major highways, the Trans-Canada #1 and Yellowhead #16. Both are excellent birding areas! Oh! ....... don't forget, birdwatching in Saskatchewan is a year round activity. While migration provides a tremendous opportunity to see vast numbers of birds, winter birding offers you an incomparable opportunity to view many species of owls and woodpeckers and other Arctic residents such as Gyrfalcons, Snowy Owls and massive flocks of Snow Buntings. -

SERVICE LIST Updated May 22, 2018

COURT FILE NUMBER Q.B. 783 of 2017 COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH FOR SASKATCHEWAN IN BANKRUPTCY AND INSOLVENCY JUDICIAL CENTRE SASKATOON PLAINTIFF AFFINITY CREDIT UNION 2013 DEFENDANT VORTEX DRILLING LTD. IN THE MATTER OF THE RECEIVERSHIP OF VORTEX DRILLING LTD. SERVICE LIST Updated May 22, 2018 NAME, ADDRESS COUNSEL FOR (OR ON BEHALF OF) EMAIL ADDRESS AND FAX NUMBER SERVICE BY EMAIL MLT Aikins LLP Affinity Credit Union 2013 1500, 410 22nd Street East Saskatoon, SK S7K 5T6 Contacts: Fax: (306) 975-7145 Manda Graham [email protected] Jeffrey M. Lee, Q.C. Telephone: (306) 975-7136 Gary Cooke [email protected] [email protected] Paul Olfert Dan Polkinghorne Telephone: (306) 956-6970 [email protected] [email protected] Cassels Brock & Blackwell Vortex Drilling Ltd. Suite 1250, Millennium Tower 440 – 2nd Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2P 5E9 Fax: (403) 648-1151 Lance Williams Telephone: (604) 691-6112 Fax: (604) 691-6120 [email protected] Mary Buttery Telephone: (604) 691-6118 Fax: (604) 691-6120 [email protected] 2452927v2 NAME, ADDRESS COUNSEL FOR (OR ON BEHALF OF) EMAIL ADDRESS AND FAX NUMBER McDougall Gauley LLP Deloitte Restructuring Inc. 500 – 616 Main Street 360 Main Street, Suite 2300 Saskatoon, SK S7H 0J6 Winnipeg, MB R3C 3Z3 Fax: (204) 944-3611 Ian Sutherland Telephone: (306) 665-5417 Contact: Fax: (306) 652-1323 Brent Warga [email protected] [email protected] Craig Frith John Fritz Telephone: (306) 665-5432 [email protected] [email protected] NAME & SERVICE DETAILS NAME & SERVICE DETAILS (Parties without counsel) (Parties without counsel) Radius Credit Union Limited Southern Bolt Supply & Tools Ltd. -

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways Updated September 2011 Meadow Lake Big River Candle Lake St. Walburg Spiritwood Prince Nipawin Lloydminster wo Albert Carrot River Lashburn Shellbrook Birch Hills Maidstone L Melfort Hudson Bay Blaine Lake Kinistino Cut Knife North Duck ef Lake Wakaw Tisdale Unity Battleford Rosthern Cudworth Naicam Macklin Macklin Wilkie Humboldt Kelvington BiggarB Asquith Saskatoonn Watson Wadena N LuselandL Delisle Preeceville Allan Lanigan Foam Lake Dundurn Wynyard Canora Watrous Kindersley Rosetown Outlook Davidson Alsask Ituna Yorkton Legend Elrose Southey Cupar Regional FortAppelle Qu’Appelle Melville Newcomer Lumsden Esterhazy Indian Head Gateways Swift oo Herbert Caronport a Current Grenfell Communities Pense Regina Served Gull Lake Moose Moosomin Milestone Kipling (not all listed) Gravelbourg Jaw Maple Creek Wawota Routes Ponteix Weyburn Shaunavon Assiniboia Radwille Carlyle Oxbow Coronachc Regway Estevan Southeast Regional College 255 Spruce Drive Estevan Estevan SK S4A 2V6 Phone: (306) 637-4920 Southeast Newcomer Services Fax: (306) 634-8060 Email: [email protected] Website: www.southeastnewcomer.com Alameda Gainsborough Minton Alida Gladmar North Portal Antler Glen Ewen North Weyburn Arcola Goodwater Oungre Beaubier Griffin Oxbow Bellegarde Halbrite Radville Benson Hazelwood Redvers Bienfait Heward Roche Percee Cannington Lake Kennedy Storthoaks Carievale Kenosee Lake Stoughton Carlyle Kipling Torquay Carnduff Kisbey Tribune Coalfields Lake Alma Trossachs Creelman Lampman Walpole Estevan -

Uv1 Uv8 Uv2 Uv3 Uv3 Uv1 Uv2 Uv8

Rg. 10 Rg. 9 Rg. 8 Rg. 7 Rg. 6 Rg. 5 Rg. 4 Rg. 3 Rg. 2 Rg. 1 Rg. 33 Rg. 32 Rg. 31 Rg. 30 Rg. 29 Rg. 28 Rg. 27 Rg. 26 Rg. 25 Rg. 24 ") ") COMMUNTY Peebles Pipestone Provincial Community Pasture UV264 UV8 MUNICIPAL BOUNDARY Windthorst Moosomin UV467 Twp. 14 CHESTER ") Kipling ") Miniota ELEMENT ASSESSMENT AREA MARTIN UV474 ") SILVERWOOD MOOSOMIN Archie ") 24 KINGSLEY Miniota UV Hamiota INDIAN RESERVE PROTECTED AREA Fleming 83 UV Twp. 13 ") PROVINCIAL PARK 5550000 UV41 1 Vandura UV WATER BODY Kirkella ") WATERCOURSE Prairie National Wildlife Area Corning ") ") Kelso BAKKEN PIPELINE PROJECT GOLDEN WEST Twp. 12 ") Elkhorn ") UV259 RAILWAY HAZELWOOD WAWKEN Lenore UV47 Elkhorn UV8 ") HIGHWAY Wawota WALPOLE ") Wallace Woodworth TRANSMISSION LINE Handsworth 542 Twp. 11 Pleasant Rump UV PIPELINE Nakota Band Fairlight MARYFIELD ") P L I.R. 68B i i g p h Little t e n ") s i S t n o )" BAKKEN PUMP STATION Kenosee g t n 254 C 48 o e Kenosee Lake n C V Lake r UV U y 1 e Pleasant Rump r e C e 256 k UV e r k V Nakota Band e U Kenosee") e Virden " I.R. 68 Maryfield k ) EPI CROMER TERMINAL 5525000 Lake ") UV257 Virden ") Moose Mountain Provincial Park !< BLOCK VALVE SITE J Twp. 10 a Au c b k White Bear u s r o (Carlyle) Cannington n G n t a o C n i Lake Lake n r e C s e b k r o GRIFFIN Tecumseh Community Pasture White Bear e ro e u I.R. -

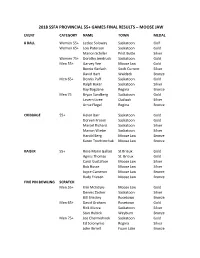

2018 Ssfa Provincial 55+ Games Final Results – Moose

2018 SSFA PROVINCIAL 55+ GAMES FINAL RESULTS – MOOSE JAW EVENT CATEGORY NAME TOWN MEDAL 8 BALL Women 55+ Lezlee Soloway Saskatoon Golf Women 65+ Lois Paterson Saskatoon Gold Marion Schiller Pilot Butte Silver Women 75+ Dorothy Jendruck Saskatoon Gold Men 55+ Garvey Yee Moose Jaw Gold Bernie Gerlach Swift Current Silver David Hart Waldeck Bronze Men 65+ Dennis Puff Saskatoon Gold Ralph Baker Saskatoon Silver Ray Bogdane Regina Bronze Men 75 Bryan Sandberg Saskatoon Gold Lavern Lizee Outlook Silver Arnie Flegel Regina Bronze CRIBBAGE 55+ Helen Barr Saskatoon Gold Doreen Froom Saskatoon Gold Marcel Richard Saskatoon Silver Marion Wiebe Saskatoon Silver Harold Berg Moose Jaw Bronze Karen Trochimchuk Moose Jaw Bronze KAISER 55+ Rose Marie Gallais St Brieux Gold Agnes Thomas St. Brieux Gold Carol Gustafson Moose Jaw Silver Bob Busse Moose Jaw Silver Joyce Cameron Moose Jaw Bronze Rudy Friesen Moose Jaw Bronze FIVE PIN BOWLING SCRATCH Men 55+ Kim McIntyre Moose Jaw Gold Dennis Zacher Saskatoon Silver Bill Shkolny Rosetown Bronze Men 65+ David Graham Rosetown Gold Rick Murza Saskatoon Silver Stan Hubick Weyburn Bronze Men 75+ Joe Chermishnok Saskatoon Gold Ed Solonynko Regina Silver John Birrell Foam Lake Bronze Men 85+ Raymond Johnson Kelvington Gold Sandy Ramage Moose Jaw Silver SCRATCH Women 55+ Jo-Ann Paxman Weyburn Gold Linda McIntyre Moose Jaw Silver Hope Smith Pierceland Bronze Women 65+ Jutta Zarzycki Saskatoon Gold Dorina Mareschal Rosetown Silver Linda Brown Regina Bronze Women 75+ Jacqueline Laviolette Swift Current Gold Women 85+ -

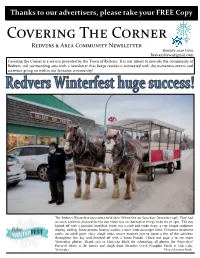

January 2020 Issue [email protected] Covering the Corner Is a Service Provided by the Town of Redvers

Thanks to our advertisers, please take your FREE Copy Covering The Corner Redvers & Area Community Newsletter January 2020 Issue [email protected] Covering the Corner is a service provided by the Town of Redvers. It is our intent to provide the community of Redvers and surrounding area with a newsletter that keeps residents connected with the numerous events and activities going on within our fantastic community! The Redvers Winterfest committee held their Winterfest on Saturday, December 14th. They had so many activities planned for the day, there was no shortage of things to do for all ages. The day kicked off with a pancake breakfast, there was a craft and trade show, a rice krispie sculpture display, curling, Santa photos, bouncy castles, a town wide scavenger hunt, Christmas ornament crafts, an adult paint class, sleigh rides, movie matinee just to name a few of the activities throughout the day and finished off with a Santa Parade. Check out page 7 to see more Winterfest photos. Thank you to Christina Birch for submitting all photos for Winterfest! Pictured above is the horses and sleigh from Meander Creek Pumpkin Patch at Oak Lake, Manitoba. Photo/Christina Birch TEEING UP TO SUPPORT COMMUNITY RESCUE COMMITTEE, RED COAT MUTUAL AID Submitted The WBL Ladies Tournament hosted by the Drive for Lives Committee was a ladies’ day out to enjoy camaraderie of good friends and sharing laughs on a spectacular golf course while supporting a life-saving organization. On July 19th, White Bear Lake Golf Course once again was bombarded with fun-loving women at the annual Drive for Lives Ladies Golf Tournament. -

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction a Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction A Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada Len Garis, Sarah Hughan, Paul Maxim, and Alex Tyakoff October 2016 Executive Summary Despite the steady reduction in rates of fire that have been witnessed in Canada in recent years, ongoing research has demonstrated that there continue to be striking inequalities in the way in which fire risk is distributed through society. It is well-established that residential dwelling fires are not distributed evenly through society, but that certain sectors in Canada experience disproportionate numbers of incidents. Oftentimes, it is the most vulnerable segments of society who face the greatest risk of fire and can least afford the personal and property damage it incurs. Fire risks are accentuated when property owners or occupiers fail to install and maintain fire and life safety devices such smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors in their homes. These life saving devices are proven to be highly effective, inexpensive to obtain and, in most cases, Canadian fire services will install them for free. A key component of driving down residential fire rates in Canadian cities, towns, hamlets and villages is the identification of communities where fire risk is greatest. Using the internationally recognized Home Safe methodology described in this study, the following Aboriginal and Non- Aboriginal communities in provinces and territories across Canada are determined to be at heightened risk of residential fire. These communities would benefit from a targeted smoke alarm give-away program and public education campaign to reduce the risk of residential fires and ensure the safety and well-being of all Canadian citizens. -

Health Care Services Guide

423 Health Care Services Guide Sun Country Health Region TABLE OF CONTENTS SERVING THE MUNICIPALITIES AND SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES OF..... Health Region Office ................................424 Alameda Fife Lake Kisbey Pangman General Inquiries ......................................424 Ambulance ................................................424 Alida Fillmore Lake Alma Radville Bill Payments ...........................................424 Antler Forget Lampman Redvers Communications ......................................424 Arcola Frobisher Lang Roche Percee Employment Opportunities .....................424 Bengough Gainsborough Macoun Storthoaks Quality of Care Coordinator ....................424 Bienfait Gladmar Manor Stoughton Health Care Services Guide 24 Hour Help/Information Lines ..............424 Carievale Glen Ewen Maryfield Torquay Health Care Services ................................424 Carlyle Glenavon McTaggart Tribune Home Care .................................................425 Carnduff Goodwater Midale Wawota Health Care Facilities ...............................425 Ceylon Halbrite Minton Weyburn District Hospitals ......................................425 Coronach Heward North Portal Windthorst Community Hospitals ...............................425 Creelman Kennedy Ogema Yellow Grass Health Centres ..........................................425 Estevan Kenosee Lake Osage Long Term Care Facilities ........................426 Fairlight Kipling Oxbow HealthLine .................................................426 Telehealth -

Ressources Naturelles Canada

111° 110° 109° 108° 107° 106° 105° 104° 103° 102° 101° 100° 99° 98° n Northwest Territories a i d n i a r i e Territoires du Nord-Ouest d M i n r a e h i Nunavut t M 60° d r 60° i u r d o e n F M o c e d S r 1 i 2 h 6 23 2 2 T 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 126 12 11 10 9 Sovereign 4 3 2 125 8 7 6 5 4 3 9 8 7 6 5 Thainka Lake 23 Lake 19 18 17 16 15 13 12 11 10 Tazin Lake Ena Lake Premier 125 124 125 Lake Selwyn Lake Ressources naturelles Sc ott Lake Dodge Lake 124 123 Tsalwor Lake Canada 124 Misaw Lake Oman Fontaine Grolier Bonokoski L. 123 1 Harper Lake Lake 22 Lake 123 Lake Herbert L. Young L. CANADA LANDS - SASKATCHEWAN TERRES DU CANADA – SASKATCHEWAN 122 Uranium City Astrolabe Lake FIRST NATION LANDS and TERRES DES PREMIÈRES NATIONS et 121 122 Bompas L. Beaverlodge Lake NATIONAL PARKS OF CANADA PARCS NATIONAUX DU CANADA 121 120 121 Fond du Lac 229 Thicke Lake Milton Lake Nunim Lake 120 Scale 1: 1 000 000 or one centimetre represents 10 kilometres Chipman L. Franklin Lake 119 120 Échelle de 1/1 000 000 – un centimètre représente 10 kilomètres Fond du Lac 227 119 0 12.5 25 50 75 100 125 150 1 Lake Athabasca 18 Fond-du-Lac ! 119 Chicken 225 Kohn Lake Fond du Lac km 8 Fond du Lac 228 Stony Rapids 11 117 ! Universal Transverse Mercator Projection (NAD 83), Zone 13 233 118 Chicken 226 Phelps Black Lake Lake Projection de Mercator transverse universelle (NAD 83), zone 13 Fond du Lac 231 117 116 Richards Lake 59° 59° 117 Chicken NOTE: Ath 224 This map is an index to First Nation Lands (Indian Lands as defined by the Indian Act) abasca Sand Dunes Fond du Lac 232 Provincial Wilderne Black Lake 116 1 ss Park and National Parks of Canada. -

New Breed MAGAZINE

New Breed MAGAZINE Summer Fall 2007 Editors: Darren R. Préfontaine [email protected] Karon Shmon [email protected] David Morin is a publication of Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies [email protected] and Applied Research in partnership with the Métis Nation - Janessa Temple Saskatchewan. [email protected] Any correspondence or inquiries can be made to: The Gabriel Dumont Institute Editorial Board: 2-604 22nd Street West Saskatoon, SK S7M 5W1 Geordy McCaffrey, Executive Director Telephone: 306.657.5716 Facsimile: 306.244.0252 Karon Shmon, Publishing Coordinator New Breed Magazine is published quarterly. Contributing Writers: All views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the various authors and are not necessarily those Boyer, Mary Rose of the Gabriel Dumont Institute, its Executive, or of the Métis Hudy, Rose Nation - Saskatchewan. Moine, Louise No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any shape Morin, David or form without the express written consent of New Breed Nicholat, Christa Magazine and the Gabriel Dumont Institute. Préfontaine, Darren Advertising rates are posted on the last page of the Temple, Janessa magazine, or can be obtained by contacting New Breed Magazine at the Gabriel Dumont Institute. Front Cover Pictures: Advertisers and advertising agencies assume full responsibility for all content of advertisements printed. Top left Louis Chatelaine Advertisers also assume responsibility for any claim arising therefrom made against New Breed Magazine or the Gabriel Top centre Edith Merrifield Dumont Institute. Top right Edward King Bottom left Maxim Collins and New Breed Magazine can be purchased for $4.00 at the Gabriel Dumont Institute. -

Canadian Studies

TRENT UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES NEWS Number 53, April 2015 Canadian Studies: In this issue: a key moment of enquiry This issue of Archives News highlights key holdings in the Archives and Spe- We are excited to be registered for the upcoming International cial Collections which pertain to Cana- Canadian Studies Conference, Contesting Canada’s Future, to be da. Given the upcoming international held at Trent University, May 21-23. While keeping an eye on the conference on Canadian Studies to be future, the Conference will examine the role that Trent has played held at Trent in May, and the fact that in shaping the study of Canada throughout the world. Canada is well represented in the holdings of Trent University Archives. We our holdings invariably pertain to our hold a broad range of interdisciplinary materials while also pre- nation, this is a timely focus for our serving historically significant materials pertaining to Peterborough newsletter. Details about the confer- and the surrounding areas. On many levels, the documents reveal ence, intriguingly titled Contesting Can- “contested” visions of what Canada means; included are minute ada’s Future, are available at the follow- books of the Iron Moulders’ Union Local 191, pamphlets of We- ing link: Peterborough (the local branch of the Alliance for Non-Violent Ac- http://www.trentu.ca/canadaconference2015/ tion), Tea Meeting advertisements of the Sons of Temperance and the private letters of individuals where more subtly expressed di- We are very pleased to be a host site of vergences connected to class, race and gender are found. Con- Doors Open Peterborough this year. -

Saskatchewan's Long History of Coal Mining

Saskatchewan’s Long History of Coal Mining by Janet MacKenzie Western Development Museum 6 February 2003 Saskatchewan’s Long History of Coal Mining The farmer those days barely made a living and without the coal mine would have barely existed. Would the train have come to this area? I doubt it. Would the Power Plant that feeds electricity to that area exist? No. I could go on and on. We owe a huge debt to Coal and the Miners who worked with it. ( Gent 1998) 1. Introduction Dating back to 1857, coal mining is one of the earliest resources to be mined in the province. For more than 50 years coal provided a cheap domestic and commercial fuel. Today it is much more widely used. About 90% goes to the production of electricity to provide light and power to farms, towns and villages, cities around the province and beyond. What was begun by enterprising settlers grubbing out coal for their own use evolved into a huge industry in which desperately poor miners slaved in dangerous underground mines. Today, the southern coalfields prosper and miners work for excellent wages and in relative safety. What is Coal? Coal is about 100 million years old, formed from buried swamp plants at the edges of ancient seas. The plant matter has been converted into a fuel by pressure and heat. Because plants differ and they are buried at varying depths which have been under varying amounts of pressure and heat, there are differences between coal deposits from place to place. Coal classification by "rank" is based on how much of the original plant matter has transformed into carbon.