Un-Defining Disability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Open Letter to Hollywood Executives

An Open Letter To Hollywood Executives We, the undersigned, are actors, producers, and industry creatives concerned about the epidemic of gun violence sweeping our country, and are joining forces to do everything we can to help build safer communities for us all. Over the last several months, large American companies have urged policymakers to enact bipartisan legislation to address this epidemic. Some of you have joined these public calls, but we believe that there’s more you can do. The annual awards season shines a spotlight on our industry and provides you with the opportunity to take direct action that will save lives all across this country. That’s why we are calling on all major Hollywood studios to: 1. End political contributions to candidates who take money from the NRA and vote against gun reform. From 2016 to 2020, the political action committees associated with the studios behind this year’s Best Picture Oscar nominees donated a combined total of $4.2 million to NRA-backed lawmakers. These lawmakers’ opposition to gun reform is literally putting our audiences in danger and we are urging you to consider a politician’s position on gun reform when political contributions in the future. 2. Use your political clout and leverage in Congress to actively lobby for gun reform. Keeping everyone safe should be a top corporate priority for all of us. 3. Support gun violence survivors and gun violence intervention programs to help reduce everyday gun violence all across this country. Since the federal government has failed to pass reforms that raise the standard for gun ownership in America, our industry has a responsibility to act. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

Who's Telling My Story?

LESSON PLAN Level: Grades 9 to 12 About the Author: Matthew Johnson, Director of Education, MediaSmarts Duration: 2 to 3 hours This lesson was produced with the support of the Government of Canada through the Department of Justice Canada's Justice Partnership and Innovation Program. Who’s Telling My Story? This lesson is part of USE, UNDERSTAND & CREATE: A Digital Literacy Framework for Canadian Schools: http://mediasmarts.ca/teacher-resources/digital-literacy-framework. Overview In this lesson students learn about the history of blackface and other examples of majority-group actors playing minority -group characters such as White actors playing Asian and Aboriginal characters and non-disabled actors playing disabled characters. They consider the key media literacy concepts that “audiences negotiate meaning” and “media contain ideological and value messages and have social implications” in discussing how different kinds of representation have become unacceptable and how those kinds of representations were tied to stereotypes. Finally, students discuss current examples of majority-group actors playing minority-group characters and write and comment on blogs in which they consider the issues raised in the lesson. Learning Outcomes Students will: learn about the history and implications of majority-group actors playing minority-group characters consider the importance of self-representation by minority communities in the media state and support an opinion write a persuasive essay Preparation and Materials Read Analyzing Blackface (Teacher’s Copy) Prepare to show the A History of Blackface slideshow and Blackface Then and Now video to the class Copy the following handouts: Analyzing Blackface Cripface www.mediasmarts.ca 1 © 2016 MediaSmarts Who’s Telling My Story? ● Lesson Plan ● Grades 9 – 12 Procedure Begin by projecting the first two images from “A History of Blackface”: Carlo Rota and Kevin McHale, from series currently on TV (2011). -

Download Choosing Glee

Choosing Glee: 10 Rules to Finding Inspiration, Happiness, and the Real You, Jenna Ushkowitz, Sheryl Berk, St. Martin's Press, 2013, 1250030617, 9781250030610, 224 pages. Glee star Jenna Ushkowitz, a.k.a. "Tina," inspires fans to invoke positive thinking into everything they do in this inspirational scrapbook.Time to Gleek out!Fans of the breakout musical series will flock to Ushkowitz’s heartfelt and practical guide on how to be your true self, gain self-esteem, and find your inner confidence. In Choosing Glee, Jenna shares her life in thrall to performance, navigating the pendulum swing of rejection and success, and the lessons she learned along the way. Included are her vivid anecdotes of everything before and after Glee: her being adopted from South Korea; her early appearances in commercials and on Sesame Street; her first Broadway role in The King and I; landing the part of Tina on Glee; her long-time friendships with Lea Michele (a.k.a. Rachel Berry) and Kevin McHale (a.k.a. Artie); and touring the world singing the show’s hits to stadium crowds. Peppered throughout are photos, keepsakes, lists, and charts that illustrate Jenna's life and the choices she has made that have shaped her positive outlook.Choosing Glee will speak to the show's demographic who are often coping with the very stresses and anxieties the teenage characters on Glee face. Think The Happiness Project for a younger generation: With its uplifting message and intimate format, teens can learn how, exactly, to choose glee. -

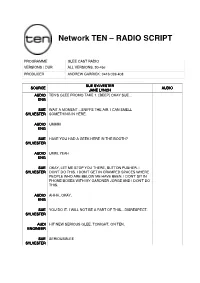

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT PROGRAMME GLEE CAST RADIO VERSIONS / DUR ALL VERSIONS. 30-45s PRODUCER ANDREW GARRICK: 0416 026 408 SUE SYLVESTER SOURCE AUDIO JANE LYNCH AUDIO TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] OKAY SUE… ENG SUE WAIT A MOMENT…SNIFFS THE AIR. I CAN SMELL SYLVESTER SOMETHING IN HERE. AUDIO UMMM ENG SUE HAVE YOU HAD A GEEK HERE IN THE BOOTH? SYLVESTER AUDIO UMM, YEAH ENG SUE OKAY, LET ME STOP YOU THERE, BUTTON PUSHER. I SYLVESTER DON'T DO THIS. I DON'T GET IN CRAMPED SPACES WHERE PEOPLE WHO ARE BELOW ME HAVE BEEN. I DON'T SIT IN PHONE BOXES WITH MY GARDNER JORGE AND I DON'T DO THIS. AUDIO AHHH..OKAY. ENG SUE YOU DO IT. I WILL NOT BE A PART OF THIS…DISRESPECT. SYLVESTER AUDI HIT NEW SERIOUS GLEE. TONIGHT, ON TEN. ENGINEER SUE SERIOUSGLEE SYLVESTER Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT FINN HUDSON SOURCE AUDIO CORY MONTEITH FEMALE TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. THANKS. HI AUSTRALIA, IT'S FINN HUSON HERE, HUDSON FROM TEN'S NEW SHOW GLEE. FEMALE IT'S REALLY GREAT, AND I CAN ONLY TELL YOU THAT IT'S FINN COOL TO BE A GLEEK. I'M A GLEEK, YOU SHOULD BE TOO. HUDSON FEMALE OKAY, THAT'S PRETTY GOOD FINN. CAN YOU MAYBE DO IT AUDIO WITH YOUR SHIRT OFF? ENG FINN WHAT? HUDSON FEMALE NOTHING. AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY… HUDSON FEMALE MAYBE JUST THE LAST LINE AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. UMM. GLEE – 730 TONIGHT, ON TEN. SERIOUSGLEE HUDSON FINN OKAY. -

1 Nominations Announced for the 19Th Annual Screen Actors Guild

Nominations Announced for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Ceremony will be Simulcast Live on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2013 on TNT and TBS at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) LOS ANGELES (Dec. 12, 2012) — Nominees for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® for outstanding performances in 2012 in five film and eight primetime television categories as well as the SAG Awards honors for outstanding action performances by film and television stunt ensembles were announced this morning in Los Angeles at the Pacific Design Center’s SilverScreen Theater in West Hollywood. SAG-AFTRA Executive Vice President Ned Vaughn introduced Busy Philipps (TBS’ “Cougar Town” and the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® Social Media Ambassador) and Taye Diggs (“Private Practice”) who announced the nominees for this year’s Actors®. SAG Awards® Committee Vice Chair Daryl Anderson and Committee Member Woody Schultz announced the stunt ensemble nominees. The 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® will be simulcast live nationally on TNT and TBS on Sunday, Jan. 27 at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) from the Los Angeles Shrine Exposition Center. An encore performance will air immediately following on TNT at 10 p.m. (ET)/7 p.m. (PT). Recipients of the stunt ensemble honors will be announced from the SAG Awards® red carpet during the tntdrama.com and tbs.com live pre-show webcasts, which begin at 6 p.m. (ET)/3 p.m. (PT). Of the top industry accolades presented to performers, only the Screen Actors Guild Awards® are selected solely by actors’ peers in SAG-AFTRA. -

Baltimore Folk Music Society Member, Country Dance & Song Society September 2014

Baltimore Folk Music Society Member, Country Dance & Song Society September 2014 BFMS American Contra & Square Dance* BFMS English Country Dance* Lovely Lane United Methodist Church Saint Mark's on-the-Hill Parish Hall 2200 Saint Paul St, Baltimore 21218 1620 Reisterstown Rd, Pikesville 21208 Use parking lots on either side of 23rd St. at Saint Paul 0.5 miles from Balt. Beltway Exit 20 South Wednesday evenings, 8-10:30 pm Monday evenings, 8-10:30 pm English Country Dancing is New dancer session at 7:30 on the second and fourth lively movement to elegant music in a friendly, informal Wednesdays of the month setting. All dances are taught and walked through. Admission: $13/$9 for BFMS members & affiliates. New dancer session at 7:45 on the first Monday of the month This September all students with ID dance free! $11/$8 for BFMS members & affiliates; $2 student discount Info: Perry Shafran at [email protected] Info: Carl Friedman at 410-321-8419 or [email protected] http://bfms.org/squarecontra.php http://bfms.org/mondayDance.php Sept 3—Laura Brown calls to A.P. and the Banty Roosters Sept 1— New Dancers Workshop (free) at 7:45 PM – Andy Porter (fiddle), Joe Langley (guitar), Mark Lynch Sharon McKinley calls to Jeff Steinberg (violin), Marty (mandolin), and Artie Abrams (bass). Taylor (winds, concertina) and Mark Vidor (accordion). Sept 10—Perry Shafran calls to Old Time Jam Band. New Sept 8— Carl Friedman calls to Emily Aubrey (violin), dancer orientation at 7:30 pm Steve Epstein (clarinet), and Francine Krasowska (piano). -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

Beliefs About Individuals with Disability As Related to Media Portrayal of Disability in Glee

BELIEFS ABOUT INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITY AS RELATED TO MEDIA PORTRAYAL OF DISABILITY IN GLEE _______________________________________ A thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by EMILY LORENZ Dr. Cynthia M. Frisby, Ph.D., MAY 2016 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis titled BELIEFS ABOUT INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITY AS RELATED TO MEDIA PORTRAYAL OF DISABILITY IN GLEE presented by Emily Lorenz, a candidate for the degree of master of arts and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Dr. Cynthia M. Frisby Professor Dr. Elizabeth (Lissa) Behm-Morawitz Professor Dr. Sungkyoung Lee Professor Dr. Cristina Mislán DEDICATION In loving memory of mom, Janice Peurrung, I would not be who I am without her, and this research would not exist. With love and gratitude, dedicated to Kevin, Lily, Michael, and Kate – everything I do, I do for and because of my family. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you Dr. Frisby, you are truly an inspiration and your support through this process has been invaluable. I am grateful for your positive attitude, dedication and support in my research. Thank you also to Dr. Elizabeth (Lissa) Behm-Morawitz, Dr. Sungkyoung Lee and Dr. Cristina Mislán for serving on my committee and helping make my dream a reality. Finally, thank you to Sarah Smith-Frigerio for her support, encouragement and answering myriad questions for me during the past eight (yes, I said eight) years since I started this master’s program. -

8Th ANNUAL TV LAND AWARDS”

THE CAST OF “EVERYBODY LOVES RAYMOND,” MEL BROOKS, CARL REINER AND CAST MEMBERS FROM “CHARLIE’S ANGELS” AND “GLEE” TOP THE LIST OF TALENT TO BE HONORED AT THE “8th ANNUAL TV LAND AWARDS” Pop Culture Award To Be Given To “Charlie’s Angels” With Special Tribute To Farrah Fawcett Annual TV Land PRIME Original Special Taping Saturday, April 17 At 4:00 p.m. on Sony’s Historic Stage 15 in Culver City, CA And Will Air On April 25 At 9:00 p.m. ET/PT March 15, 2010, Los Angeles, CA – TV Land announced today that legendary comedians Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner; the cast of “Everybody Loves Raymond” including Ray Romano, Brad Garrett, Patricia Heaton, Doris Roberts, Madylin Sweeten, Sawyer Sweeten and Sullivan Sweeten; “Charlie’s Angels” stars Cheryl Ladd, Jaclyn Smith and “Glee” cast members Jane Lynch, Dianna Agron, Jayma Mays, Jessalyn Gilsig and Kevin McHale are among the honorees at this year’s “8th Annual TV Land Awards” with more talent to be announced soon. The gala is scheduled to be taped on Saturday, April 17 on the historic Stage 15 on the Sony Lot in Culver City. The show premieres on Sunday, April 25 at 9:00 p.m. ET/PT. The entire cast of “Everybody Loves Raymond” will reunite for the first time since the death of fellow cast member Peter Boyle to receive the Impact Award at this year’s show. “Everybody Loves Raymond” ran on CBS for nine successful seasons and joins the TV Land line-up on March 18. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Cast Members from FOX's New Musical Comedy Series GLEE to Ring the NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell

Cast Members From FOX's New Musical Comedy Series GLEE to Ring The NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell ADVISORY, Sep 29, 2009 (GlobeNewswire via COMTEX News Network) -- What: Cory Monteith and Amber Riley from FOX's new musical comedy series, GLEE, will preside over the NASDAQ Closing Bell to celebrate the show's first season pick-up. GLEE airs on Wednesday's at 9:00-10:00 PM ET/PT on FOX. Where: NASDAQ MarketSite - 4 Times Square - 43rd & Broadway - Broadcast Studio When: Wednesday, September 30th 2009 at 3:45 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. ET Contacts: Elissa Johansmeier Vice President, Publicity & Corporate Communications Fox Broadcasting Company phone: 212-556-2567 email: [email protected] NASDAQ MarketSite: Jolene Libretto (646) 441-5220 [email protected] Feed Information: The Closing Bell is available from 3:50 p.m. to 4:05 p.m. on AMC-3/C-3 (ul 5985V; dl 3760H). The feed can also be found on Ascent fiber 1623. If you have any questions, please contact Jolene Libretto at (646) 441-5220. Radio Feed: An audio transmission of the Closing Bell is also available from 3:50 p.m. to 4:05 p.m. on uplink IA6 C band / transponder 24, downlink frequency 4180 horizontal. The feed can be found on Ascent fiber 1623 as well. Webcast: A live webcast of the NASDAQ Closing Bell will be available at: http://www.nasdaq.com/about/marketsitetowervideo.asx Photos: To obtain a high-resolution photograph of the Market Close, please go to http://www.nasdaq.com/reference/marketsite_events.stm and click on the market close of your choice.