Josef Tal (Israel)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josef Tal on the Cusp of Israeli Statehood, Or, the Simultaneity of Adjacency and Oppositionality

Josef Tal on the Cusp of Israeli Statehood, or, The Simultaneity of Adjacency and Oppositionality Assaf Shelleg Acta Musicologica, Volume 91, Number 2, 2019, pp. 146-167 (Article) Published by International Musicological Society For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/741611 Access provided at 28 Nov 2019 16:05 GMT from Tel Aviv University i i i i Josef Tal on the Cusp of Israeli Statehood, or, The Simultaneity of Adjacency and Oppositionality Assaf Shelleg Jerusalem To the amateur composer who comes to this country with an inheritance of Russian of Balkan folk tunes, the absorption of the Oriental Jewish and Arabian music is a gain. The traditionalism of his original country receives a new accent. To the professional composer whose material is the European art-music, the Jewish and Arab-Palestinian folklore opens up a fertile and rejuvenating world. A few will attach certain ourishes, some popular syl- lables to the iron structure of modern art-language; in other words they write a kind of “quotation-music” with wrong notes.1 [Sharett’s music] demonstrates neither melodic templates in their conven- tional form nor harmonies using parallel fourths and fths mixed with seconds—a falsied acoustic substitute; nor is there any articial immer- sion in the past in the form of shallow mimicry of biblical chants. We must not follow the easy path of success, but rather aspire to achieve in our spiritual creation what we had accomplished politically.2 The statements “‘quotation music’ with wrong notes,” “fal- sied acoustics,” and “shallow mimicry of biblical chants” could have equally come from either of the composers, Stefan Wolpe or Josef Tal. -

A Librettist's Reflections on Opera in Our Times

Israel Eliraz A LIBRETTIST'S REFLECTIONS ON OPERA IN OUR TIMES [1] Pierre Boulez may have mourned the death of the opera and suggested setting fire to opera houses (he has repented since and has even written in this rnusical form himsel~, but the Old Lady is still going strong. She is no Ionger as regal and as much admired as in the 18th century, nor is she as popular and vital as she was in mid-I9th century for bold young rivals have entered the arena: film, radio, musicals and television. But reviewing the new operas written in this century, from MOSES UND ARON by Schoenberg and WOZZECK by Berg, to works by Luigi Dallapiccola, lldebrando Pizzetti, Werner Egk, Marcel Delannoy and others, one is taken by surprise by the abundance, versatility and ingenuity in musical, theatrical and ideological terms, of modern opera. What the rnusical avant -garde considered a defunct creature, a 'dinosaur' of sorts (this strange animal is over 370 years old), became, to their dismay, a phoenix redux. At tirnes it metarnorphosed into political drarna (Weiii-Brecht); at others it returned to the oratory form (Stravinsky, Honegger, Debussy), and on still other occasions it turns upon itself with laudable irony, as in Mauricio Kagel's STAATSTHEATER. Anylhing can happen in an opera, all is allowed and, if one rnay venture to express some optirnisrn - which is not easy in our province - it still has some surprises in store for us. [2] Music Iovers have been accustorned to think that it is in the nature of opera to address the 'larger issues'- biblical, rnylhological, historical, national. -

Edition 31 Berliner Festspiele 2021

Ed. 31 '21 Die Editionsreihe der Berliner Festspiele erscheint bis zu sechsmal jährlich und präsentiert Originaltexte und Kunstpositionen. Bislang erschienen: Edition 1 Hanns Zischler, Großer Bahnhof (2012) Christiane Baumgartner, Nachtfahrt (2009) Edition 2 Mark Z. Danielewski, Only Revolutions Journals (2002 – 2004) Jorinde Voigt, Symphonic Area (2009) Edition 3 Marcel van Eeden, The Photographer (1945 – 1947), (2011 – 2012) Edition 4 Mark Greif, Thoreau Trailer Park (2012) Christian Riis Ruggaber, Contemplatio I–VII: The Act of Noting and Recording (2009 – 2010) Edition 5 David Foster Wallace, Kirche, nicht von Menschenhand erbaut (1999) Brigitte Waldach, Flashfiction (2012) Edition 6 Peter Kurzeck, Angehalten die Zeit (2013) Hans Könings, Spaziergang im Wald (2012) Edition 7 Botho Strauß, Kleists Traum vom Prinzen Homburg (1972) Yehudit Sasportas, SHICHECHA (2012) Edition 8 Phil Collins, my heart’s in my hand, and my hand is pierced, and my hand’s in the bag, and the bag is shut, and my heart is caught (2013) Edition 9 Strawalde, Nebengekritzle (2013) Edition 10 David Lynch, The Factory Photographs (1986–2000) Georg Klein, Der Wanderer (2014) Edition 11 Mark Lammert, Dimiter Gotscheff – Fünf Sitzungen / Five Sessions (2013) Edition 12 Tobias Rüther, Bowierise (2014) Esther Friedman, No Idiot (1976–1979) Edition 13 Michelangelo Antonioni, Zwei Telegramme (1983) Vuk D. Karadžić, Persona (2013) Edition 14 Patrick Ness, Every Age I Ever Was (2014) Clemens Krauss, Metabolizing History (2011 – 2014) Edition 15 Herta Müller, Pepita (2015) Edition 16 Tacita Dean, Event for a Stage (2015) Edition 17 Angélica Liddell, Via Lucis (2015) Edition 18 Karl Ove Knausgård, Die Rückseite des Gesichts (2014) Thomas Wågström, Nackar / Necks (2014) Edition 31 Berliner Festspiele 2021 Angela Rosenberg Pragmatiker auf heißem Boden Gerhart von Westerman, Kunstmanager und erster Intendant der Berliner Festwochen. -

Hugh Le Caine: Pioneer of Electronic Music in Canada Gayle Young

Document généré le 25 sept. 2021 13:04 HSTC Bulletin Journal of the History of Canadian Science, Technology and Medecine Revue d’histoire des sciences, des techniques et de la médecine au Canada Hugh Le Caine: Pioneer of Electronic Music in Canada Gayle Young Volume 8, numéro 1 (26), juin–june 1984 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/800181ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/800181ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) HSTC Publications ISSN 0228-0086 (imprimé) 1918-7742 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Young, G. (1984). Hugh Le Caine: Pioneer of Electronic Music in Canada. HSTC Bulletin, 8(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.7202/800181ar Tout droit réservé © Canadian Science and Technology Historical Association / Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des Association pour l'histoire de la science et de la technologie au Canada, 1984 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ 20 HUGH LE CAINE: PIONEER OF ELECTRONIC MUSIC IN CANADA Gayle Young* (Received 15 November 1983; Revised/Accepted 25 June 1984) Throughout history, technology and music have been closely re• lated. Technological developments of many kinds have been used to improve musical instruments. -

Zeitgenössische Musik in Berlin Field Notes

Zeitgenössische Musik in Berlin fieLD NOtes Mai– Aug18 Getragen von der inm—initiative neue musik berlin e.V. Opposite Editorial: Detlef Diederichsen 1 Gastbeitrag: Auflösung oder Transformation? Gisela Nauck 2 Kurznachrichten 5 Feldfund – Konzerttipps 8 Portrait: Solistenensemble Kaleidoskop 18 Nachwuchs 22 Klangkunst 24 Festivals: mikromusik und intersonanzen 26 Veranstaltungskalender 28 Post 46 Veranstaltungsorte 48 OPPOSITE Editorial Liebe Leser*innen, einige der schönsten experimentellen Improv-Konzerte finden traditionell Anfang Mai im Tiergarten (meinem Arbeitsplatz!) statt, wenn sich Nachtigallen-Populationen aus Ost- und West- europa zu einem großen Get Together und Festival treffen und bei der Gelegenheit ihre neuesten musikalischen Entdeckungen miteinander austauschen. Immer empfehlenswert – sagenhafte bewusstseinserweiternde Epiphanien garantiert! Passend dazu machen sich im Errant Sound sieben Klang- künstler*innen unter dem Titel »Tier – Bild – Ton« Gedanken zu »neuen Verhältnissen zwischen Bild und Ton bei der Darstellung von Tieren und Pflanzen«. »Schleiereule«, »Schlinger«, »Erbse« und »Kuckuck« lauten die vielversprechenden Titel der vier präsentierten Werke, dazu werden sämtliche auf dem Errant- Sound-Podcast veröffentlichten Kompositionen zu diversen Vogelstimmen (auch Nachtigallen!) vorgestellt und diskutiert. Ein weiteres Highlight bei den Biegungen im ausland: Die australische Klangkünstlerin Alexandra Spence trifft auf die britischen Free-/Improv-Urgesteine Eddie Prévost und John Tilbury und den US-amerikanischen -

Fifty Years of Electronic Music in Israel

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231788238 Fifty years of electronic music in Israel Article in Organised Sound · August 2005 DOI: 10.1017/S1355771805000798 CITATIONS READS 3 154 1 author: Robert J. Gluck University at Albany, The State University of New York 16 PUBLICATIONS 28 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Morton Subotnick and the late 1960s Downtown Scene View project An International perspective on electroacoustic music history View project All content following this page was uploaded by Robert J. Gluck on 20 September 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Fifty years of electronic music in Israel ROBERT J. GLUCK University at Albany, PAC 312, 1400 Washington Avenue, Albany, New York 12208, USA E-mail: [email protected] The history of electronic music composition, technologies and founding figure of electronic music in Israel. Born in institutions is traced from the founding of the State of Israel present-day Poland, Tal studied during his teen years in 1948. Core developments are followed beginning with at the Staatliche Akademische Hochschule fur Music the founding generation including Joseph Tal, Tzvi Avni and in Berlin. Among his teachers was Paul Hindemith Yizhak Sadai, continuing with the second and third who, he recalls, ‘pointed me in the direction of elec- generations of musicians and researchers, living in Israel and the United States. The institutional and political dynamics of tronic music’ (Tal 2003), specifically to the studio of the field in this country are explored, with a focus on the engineer Friedrich Trautwein, best known as inventor challenges of building an audience and institutional support, of the Trautonium, a synthesizer prototype created in as well as prospects for the future. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. -

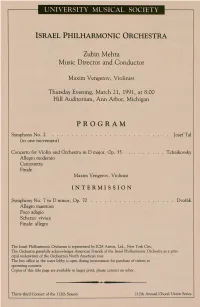

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra Program

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY ISRAEL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Zubin Mehta Music Director and Conductor Maxim Vengerov, Violinist Thursday Evening, March 21, 1991, at 8:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Symphony No. 2 ......................... Josef Tal (in one movement) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D major, Op. 35 ........ Tchaikovsky Allegro moderate Canzonetta Finale Maxim Vengerov, Violinist INTERMISSION Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 .................. DvoMk Allegro maestoso Poco adagio Scherzo: vivace Finale: allegro The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra is represented by ICM Artists, Ltd., New York City. The Orchestra gratefully acknowledges American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra as a prin cipal underwriter of the Orchestra's North American tour. The box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for purchase of tickets to upcoming concerts. Copies of this title page are available in larger print; please contact an usher. Thirty-third Concert of the 112th Season 112th Annual Choral Union Series Program Notes Symphony No. 2 transparent figures. The episodes that follow JOSEF TAL (b.1910) are in the same vein, based either upon Honoring the composer's 80th birthday linear, melodic formulation or, as in the last he Polish-born Israeli composer episode, upon strong rhythmic patterns. The Josef Tal was born September 18, work comes to its climax in the last episode, 1910, near Poznan. After study in which all the previously heard elements ing at the Hochschule fur Musik participate. After this, there is a more sub in Berlin, he emigrated to Pales dued atmosphere and, towards the conclu tineT in 1934 and taught composition and sion, the full twelve-tone-row is heard in a piano at the Jerusalem Academy of Music, melodic presentation." serving as its director from 1948 to 1952. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ New-music internationalism the ISCM festival, 1922–1939 Masters, Giles Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 New-Music Internationalism: The ISCM Festival, 1922–1939 Giles Masters PhD King’s College London 2021 Contents Abstract 3 -

Programm Als

Abschlusssymposium „Klang (ohne) Körper“ 28./29.3.2008, HKB Bern, Papiermühlestraße 13d Freitag, 28.3.08 09:00 Anmeldung, Organisation, etc. 09:45 Begrüßung und Einführung in das Thema, Daniel Weissberg und Michael Harenberg 10:45 Entwicklung des Körperbildes von der Renaissance bis heute, Michael Harenberg 11:30 Virtuosen und Maschinen, Wandlungen musikalischer Körperlichkeit, Peter Reidemeister 12:15 Mittagessen 13:30 Interfaces in der Live-Performance , Franziska Baumann 14:15 Interfaces in der vorelektronischen Musik: Klaviermechaniken, Dirigierbewegungen und historische Streichbögen, Kai Köpp 15:15 Klangerzeugung als Drama und Resonanzphänomen, Daniel Weissberg 16:15 Kaffepause 16:45 Distanzierte Verhältnisse? Die Musikinstrumentalisierung der Reproduktionsmedien und algorithmeischen Prozesse, Rolf Großmann 17:30 Podiumsdiskussion der Referenten 1 18:30 Pause 20:00 Konzert mit historischen und aktuellen Beiträgen zum Thema des Symposiums Samstag, 29.3.08 09:30 Gestorben! Aufzeichnungsmedien als Friedhöfe oder warum Aufnahmen sterben müssen. Daniel Weissberg 10:30 Kaffepause 11:00 Podiumsdiskussion der Referenten 2, mit Georg Christoph Tholen 12:30 Schluss und Verabschiedung Konzert, Freitag, 28. März, 20.00 Uhr, grosser Konzertsaal: 1. Anachronistische und synchronistische Bogenmodelle und ihre Spielweisen dargestellt an Beispielen aus fünf historischen Stilbereichen Historische Streichbögen werden als jeweils perfekt an ihr Repertoire angepasstes Instrument der Klangformung verstanden. Durch ihre inhärenten Spieleigenschaften geben -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

![The Trains Which Left) C (Lyric by Vangelis Goufas [Vah-GAY-Liss GOO-Fahss] Set to Music by Stavros Xarhakos [STAHV-Russ Ksar-HAH-Kuss]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3015/the-trains-which-left-c-lyric-by-vangelis-goufas-vah-gay-liss-goo-fahss-set-to-music-by-stavros-xarhakos-stahv-russ-ksar-hah-kuss-3163015.webp)

The Trains Which Left) C (Lyric by Vangelis Goufas [Vah-GAY-Liss GOO-Fahss] Set to Music by Stavros Xarhakos [STAHV-Russ Ksar-HAH-Kuss]

Ta trena pou figan C Ta tréna pou figan C tah TRAY-nah poo FEE-gahn C (The Trains Which Left) C (lyric by Vangelis Goufas [vah-GAY-liss GOO-fahss] set to music by Stavros Xarhakos [STAHV-russ ksar-HAH-kuss]) Tabachnik C Michel Tabachnik C mih-HELL tah-BAHCH-nyick Tabakov C Mikhail Tabakov C mee-kahEEL tah-bah-KAWF Tabard inn C At the Tabard Inn C (At the) TA-burd (Inn) C (overture by George Dyson [JAW-urj D¦-sunn]) Tabarro C Il tabarro C eel tah-BAR-ro C (The Cloak) C (an opera, with music by Giacomo Puccini [JAH-ko-mo poo-CHEE-nee]; libretto by Giuseppe Adami [joo-ZAYP-pay ah-DAH- mee] after Didier Gold [dee-deeay gawld]) Taberna C In taberna C inn tuh-BAYR-nuh C (In the tavern) C (a group of poems from the 13th-century manuscript Carmina Burana [kar-MEE-nah boo-RAH-nah] set to music by Carl Orff [KARL AWRF]) Tabernera del puerto C La tabernera del puerto C lah tah-vehr-NAY-rah dell pooEHR-toh C (an opera, with music by Pablo Sorozábal [PAH-vlo so-ro-THAH-vahl]; libretto by Romero [ro- MAY-ro] and Fernández Shaw [fehr-NAHN-dehth SHAW]) Tableaux de statistiques C tah-blo duh stah-teess-teek C (Statistical tables) C (an excerpt from the suite Souvenirs de l’exposition [sôô-v’neer duh luckss-paw-zee-seeaw6] — Remembrances of the Exposition — by Federico Mompou [feh-theh-REE-ko mawm-POOO]) Tabor C TAY-bur Tabourin C tah-bôô-reh6 C (small drum) Tabourot C Jehan Tabourot C zhehah6 tah-bôô-ro Tabuteau C Marcel Tabuteau C mar-sell tah-bü-toh Tacchinardi C Nicola Tacchinardi C nee-KO-lah tahk-kee-NAR-dee C (the first name is also spelled Niccolò