Mary W. Helms Source: Anthropos, Bd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Updated February 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45087 Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Summary Censure is a reprimand adopted by one or both chambers of Congress against a Member of Congress, President, federal judge, or other government official. While Member censure is a disciplinary measure that is sanctioned by the Constitution (Article 1, Section 5), non-Member censure is not. Rather, it is a formal expression or “sense of” one or both houses of Congress. Censure resolutions targeting non-Members have utilized a range of statements to highlight conduct deemed by the resolutions’ sponsors to be inappropriate or unauthorized. Before the Nixon Administration, such resolutions included variations of the words or phrases unconstitutional, usurpation, reproof, and abuse of power. Beginning in 1972, the most clearly “censorious” resolutions have contained the word censure in the text. Resolutions attempting to censure the President are usually simple resolutions. These resolutions are not privileged for consideration in the House or Senate. They are, instead, considered under the regular parliamentary mechanisms used to process “sense of” legislation. Since 1800, Members of the House and Senate have introduced resolutions of censure against at least 12 sitting Presidents. Two additional Presidents received criticism via alternative means (a House committee report and an amendment to a resolution). The clearest instance of a successful presidential censure is Andrew Jackson. The Senate approved a resolution of censure in 1834. On three other occasions, critical resolutions were adopted, but their final language, as amended, obscured the original intention to censure the President. -

First Phase Lifting of Mass Suspension

Mass in Church during COVID Pandemic: 1st Phase of Return 1 (Version of May 14, 2020) These directives are promulgated by the Archbishop of Santa Fe for the early lifting of the suspension of publicly-attended Mass General: Attendance limited to 10% of building capacity (per fire marshal assessment). Dispensation from Sunday obligation remains for all. Safety/ common good is priority. Coordination with staff will be essential, as will be clear and detailed communication to the people. Local pastors can make these directives more stringent as necessitated by local conditions; however, they cannot make them less strict. Reopening will be accomplished in phases. The Archbishop/Vicar General will continue to offer live stream/recorded Mass each Sunday and weekdays, and parishes are encouraged to do so as well. Social distancing/masks/increased cleaning are mandatory. Each measure presents an additional layer of protection, which individually may be insufficient. Cleaning staff should be present to disinfect commonly-touched surfaces after each Mass (pews, door handles, rails, etc.) Have on hand ample cleaning supplies, and masks if possible. Persons over 60 and with compromised immune systems should be pre-advised that they are at increased risk and be encouraged to remain home. Communicate that these guidelines are for the safety of lives and health for themselves and neighbors, and that continued opening depends on everyone’s cooperation. The Archdiocese remains responsive to changes in conditions/requirements, and will revise these instructions periodically as necessary. In Churches No open holy water present. There may be a dispenser for people to fill bottles if desired. -

The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St

NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome About NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome Title: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.html Author(s): Jerome, St. Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) (Editor) Freemantle, M.A., The Hon. W.H. (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Print Basis: New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892 Source: Logos Inc. Rights: Public Domain Status: This volume has been carefully proofread and corrected. CCEL Subjects: All; Proofed; Early Church; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. Fathers of the Church, etc. NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome St. Jerome Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page.. p. 1 Title Page.. p. 2 Translator©s Preface.. p. 3 Prolegomena to Jerome.. p. 4 Introductory.. p. 4 Contemporary History.. p. 4 Life of Jerome.. p. 10 The Writings of Jerome.. p. 22 Estimate of the Scope and Value of Jerome©s Writings.. p. 26 Character and Influence of Jerome.. p. 32 Chronological Tables of the Life and Times of St. Jerome A.D. 345-420.. p. 33 The Letters of St. Jerome.. p. 40 To Innocent.. p. 40 To Theodosius and the Rest of the Anchorites.. p. 44 To Rufinus the Monk.. p. 44 To Florentius.. p. 48 To Florentius.. p. 49 To Julian, a Deacon of Antioch.. p. 50 To Chromatius, Jovinus, and Eusebius.. p. 51 To Niceas, Sub-Deacon of Aquileia. -

The Bugnini-Liturgy and the Reform of the Reform the Bugnini-Liturgy and the Reform of the Reform

in cooperation with the Church Music Association of America MusicaSacra.com MVSICAE • SACRAE • MELETEMATA edited on behalf of the Church Music Association of America by Catholic Church Music Associates Volume 5 THE BUGNINI-LITURGY AND THE REFORM OF THE REFORM THE BUGNINI-LITURGY AND THE REFORM OF THE REFORM by LASZLO DOBSZAY Front Royal VA 2003 EMINENTISSIMO VIRO PATRI VENERABILI ET MAGISTRO JOSEPHO S. R. E. CARDINALI RATZINGER HOC OPUSCULUM MAXIMAE AESTIMATIONIS AC REVERENTIAE SIGNUM D.D. AUCTOR Copyright © 2003 by Dobszay Laszlo Printed in Hungary All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Conventions. No part of these texts or translations may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher, except for brief passages included in a review appearing in a magazine or newspaper. The author kindly requests that persons or periodicals publishing a review on his book send a copy or the bibliographical data to the following address: Laszlo Dobszay, 11-1014 Budapest, Tancsics M. u. 7. Hungary. K-mail: [email protected] Contents INTRODUCTION Page 9 1. HYMNS OF THE HOURS Page 14 2. THE HOLY WEEK Page 20 3. THE DIVINE OFFICE Page 45 4. THE CHANTS OF THE PROPRIUM MISSAE VERSUS "ALIUS CANTUS APTUS" Page 85 5. THE READINGS OF THE MASS AND THE CALENDAR Page 121 6. THE TRIDENTINE MOVEMENT AND THE REFORM OF THE REFORM Page 147 7. HIGH CHURCH - LOW CHURCH: THE SPLIT OF CATHOLIC CHURCH MUSIC Page 180 8. CHURCH MUSIC AT THE CROSSROADS Page 194 A WORD TO THE READER Page 216 Introduction The growing displeasure with the "new liturgy" introduced after (and not by) the Second Vatican Council is characterized by two ideas. -

Transcript: Suspension & Debarment

Transcript: Suspension & Debarment - Hello, and thank you for joining today's acquisition seminar hosted by the Federal Acquisition Institute. Today's seminar entitled Suspension and Debarment: What Makes a Successful Meeting will give us a glimpse into the minds of Suspension and Debarment Officials in the Federal Government, and a beind the closed door look at a successful meeting between a Suspension and Debarment Official and contractor representatives. Suspension and debarment, two terms that probably strike terror into the heart of any company or individual that wants to do business with the Federal Government. But suspension and debarment aren't meant to be punitive. And meetings with Suspension and Debarment Officials are not meant to be contentious or antagonistic. Suspension and debarment are used only as a last resort to protect the interests of the Federal Government. More often than not, a meeting with a Suspension and Debarment Official is an opportunity to help an individual or company get back on track. To enlighten us on the implications of suspension and debarment, we have a team of officials from agencies across the Federal Government. First we'll present two Suspension and Debarment Officials as they discuss, among other things, what they look for when they're determining a contractor's present responsibility and how members of the acquisition workforce can help. Then we'll present an example of a contractors meeting with a Suspension and Debarment Official. These closed door meetings have wide ranging effects on Federal Government procurement across all agencies. The meetings are necessarily private, but they are one of a Suspension and Debarment Official's most useful and effective tools for enhancing contractor responsibility. -

Exploring Solar Cycle Influences on Polar Plasma Convection

Comparison of Terrestrial and Martian TEC at Dawn and Dusk during Solstices Angeline G. Burrell1 Beatriz Sanchez-Cano2, Mark Lester2, Russell Stoneback1, Olivier Witasse3, Marco Cartacci4 1Center for Space Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas 2Radio and Space Plasma Physics, University of Leicester 3European Space Agency, ESTEC – Scientific Support Office 4Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali 52nd ESLAB Symposium Outline • Motivation • Data and analysis – TEC sources – Data selection – Linear fitting • Results – Martian variations – Terrestrial variations – Similarities and differences • Conclusions Motivation • The Earth and Mars are arguably the most similar of the solar planets - They are both inner, rocky planets - They have similar axial tilts - They both have ionospheres that are formed primarily through EUV and X- ray radiation • Planetary differences can provide physical insights Total Electron Content (TEC) • The Global Positioning System • The Mars Advanced Radar for (GPS) measures TEC globally Subsurface and Ionosphere using a network of satellites and Sounding (MARSIS) measures ground receivers the TEC between the Martian • MIT Haystack provides calibrated surface and Mars Express TEC measurements • Mars Express has an inclination - Available from 1999 onward of 86.9˚ and a period of 7h, - Includes all open ground and allowing observations of all space-based sources locations and times - Specified with a 1˚ latitude by 1˚ • TEC is available for solar zenith longitude resolution with error estimates angles (SZA) greater than 75˚ Picardi and Sorge (2000), In: Proc. SPIE. Eighth International Rideout and Coster (2006) doi:10.1007/s10291-006-0029-5, 2006. Conference on Ground Penetrating Radar, vol. 4084, pp. 624–629. -

Pope Leo of Bourges, Clerical Immunity and the Early Medieval Secular Charles West1 at First Glance, to Investigate the Secular

Pope Leo of Bourges, clerical immunity and the early medieval secular Charles West1 At first glance, to investigate the secular in the early Middle Ages may seem to be wilfully flirting with anachronism. It is now widely agreed that the early medieval political order was constructed neither against nor in opposition to the Church, but rather that the Church, or ecclesia, largely constituted that order.2 This would seem to leave little early medieval scope for the secular, understood in conventional terms as the absence of religion (and moreover often associated with modernity).3 This position is broadly reflected in the recent historiography, which focuses either on Augustine’s short-lived notion of the secular in Late Antiquity, or on the role of Gregorian Reform in beginning a slow secularisation of political authority.4 These separate approaches are spared from intersecting by the early medieval half- millennium which is presented, as so often, as either too late or too early for key developments. However, in recent years, the argument has been forcefully made across a range of fields that, far from being a neutral or universal category, the secular is in reality ‘a historically-produced idea’, and one that moreover encodes a disguised theology.5 As a consequence, ‘to tell a story 1 This paper is based on research carried out on a project funded by the AHRC 2014-16. Thanks to Emma Hunter, Conrad Leyser, Rob Priest, Steve Schoenig and Danica Summerlin for their advice on a draft, as well as to audiences at UEA and Cambridge, the class of HST 6079 in Sheffield, and the editor of this special issue. -

The Blue Hour‐ by Dennis Arculeo

THE April 2019 May 16th‐ End of Year Compeon Building G Sung Harbor 8 PM th May 4 ‐ Model Shoot ‐ Mayr Studio ‐ Staten Island Camera Club Meet‐Up reserve a seat @: hps://www.meetup.com/ Staten‐Island‐camera‐club/events/259170884/ spaces are limited. May 16th‐ End of Year Compeon ‐ Harbor Room 8:00PM Image of the Year Selecon ‐ Judge Al Brown. June 6th - Annual Awards Dinner - Real Madrid Restaurant - All are welcome - Bring a Friend - Paid Reservation is a must! June 8th Saturday Governors House Meet‐Up reserve a seat @: reserve a seat @: hps://www.meetup.com/Staten‐Island‐camera‐ club/events/ spaces are limited. Well, the End of Year Compeon is almost here. On that For those who aended in the past the menu is the same. night we will decide the Images of the Year. So come on down on May 16th.. Color and Mono Digital Images and You can secure your reservaon with a $45.00 per person pay‐ Prints will compete for the coveted awards in each of their ment on May 16that this month’s End of the Year Compe‐ respecve categories. You can enter any 4 Color or Mono on. Please bring a check payable to Staten Island Camera Club. Digital and or Print that you competed with this season. If you are not aending the End of Year Compeon, but would Here is the low down on the Awards Dinner being held on like to aend the dinner please mail your check to: Thursday June 6th, 2019. Barbara M. Hoffman at 323 Stobe Avenue, SI, NY 10306. -

Liturgy of the Hours

Liturgy of the Hours Catholic Teachings by the Deacons Deacon David Ochoa May 11, 2021 1 Opening Prayer Be at peace among yourselves. We urge you, brothers, admonish the idle, cheer the fainthearted, support the weak, be patient with all. See that no one returns evil for evil; rather, always seek what is good [both] for each other and for all. Rejoice always. Pray without ceasing. In all circumstances give thanks, for this is the will of God for you in Christ Jesus. May the God of peace himself make you perfectly holy and may you entirely, spirit, soul, and body, be preserved blameless for the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen. 2 Tonight’s Agenda • Overview – What is the Liturgy of the Hours • Importance of the Liturgy of the Hours, a Reflection • History of the Liturgy of the Hours • Current Form of the Liturgy of the Hours • How to Pray the Liturgy of the Hours • Evening Prayer for Tuesday of the 6th Week of Easter 3 • Daily prayer of the Church, marking the hours of each day and sanctifying What is the the day with Liturgy of the prayer Hours • Liturgy of the Hours is also known as the Divine Office, or the Work of God (Opus Dei) 4 Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy Sacrosanctum Concilium “By tradition going back to early Christian times, the divine office is devised so that the whole course of the day and night is made holy by the praises of God… It is the very prayer which Christ Himself, together with His body, addresses to the Father. -

Psalters and Books of Hours (Horologia)

300 Parpulov Chapter 20 Psalters and Books of Hours (Horologia) Georgi R. Parpulov Text and Illustrations A Psalter (Ψαλτήριον) contains 151 biblical psalms, always in the same sequence, plus nine or more poetic excerpts (canticles, or odes/ᾠδαί) from other books of the Bible.1 A Book of Hours (Ὡρολόγιον) contains those same odes and select psalms, re-ordered for prayer at set times of the day and night2 and intermixed with short non-biblical prayers and hymns. Additional, private prayers are sometimes appended to an Horologion or Psalter. A Psalter may also contain explanatory prefaces (such as Athanasios of Alexandria’s “Letter to Marcellinus”) and/or theological commentary running parallel to the bibli- cal text. Images may illustrate individual psalm verses and be, by way of explanation, placed close to them. In most illustrated Psalters and Horologia, however, the figural miniatures subdivide the text – just like titles do – and thus facilitate paging through it. In principle, each ode and sometimes even each psalm can be marked with a picture, but typically pictures precede the often-used Psalm 50,3 the beginning and middle of the Psalter (Ps 1 and 77), and/or the initial ode (Gen. 15:1-19) (Figs. 107-111). The illustrations can be painted with tempera or simply drawn in ink – and in the latter case, sometimes tinted with wash. They alternatively form self- contained, often framed compositions (which may or may not fill a whole 1 The chapter and verse numbers cited here are those of the Greek Old Testament (Septuagint). All quotes are from Septuagint, trans. -

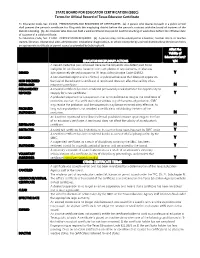

(SBEC) Terms for Official Record of Texas Educator Certificate

STATE BOARD FOR EDUCATOR CERTIFICATION (SBEC) Terms for Official Record of Texas Educator Certificate Tx. Education Code, Sec. 21.053. PRESENTATION AND RECORDING OF CERTIFICATES. (a) A person who desires to teach in a public school shall present the person's certificate for filing with the employing district before the person's contract with the board of trustees of the district is binding. (b) An educator who does not hold a valid certificate may not be paid for teaching or work done before the effective date of issuance of a valid certificate. Tx Education Code, Sec. 21.003. CERTIFICATION REQUIRED. (a) A person may not be employed as a teacher, teacher intern or teacher trainee, librarian, educational aide, administrator, educational diagnostician, or school counselor by a school district unless the person holds an appropriate certificate or permit issued as provided by Subchapter B. Affect the Validity of Educator’s Cert.? EDUCATOR DISCIPLINARY ACTIONS Y/N A denied credential was not issued because the requestor was determined to be ineligible for certification, based on non-completion of requirements, or else was DENIED administratively denied pursuant to 19 Texas Administrative Code §249.12. Y A non-inscribed reprimand is a formal, unpublished censure that does not appear on NON INSCRIBED the face of the educator’s certificate. A reprimand does not affect the validity of an REPRIMAND educator’s certificate. N PERMANENTLY A revoked certificate has been rendered permanently invalid without the opportunity to REVOKED reapply for a new certificate. Y A probated suspension is a suspension that is not enforced as long as the conditions of probation are met. -

APOSTOLIC MAI\DATE of SUSPENSION

] APOSTOLIC MAI\DATE Of SUSPENSION. E, Most lllustrious & Most Reverend Lord JAMES ATKINSON-WAKE. OSB. Archbishop. FIEREBY declare as of this day I date is suspended as a Titular Bishop RICKY O ALCANTARA with immediate effect. He has no I authority to say Mass in public only in private at this stage. He has disobeyed a public document agreed in September 2018 by the Philippine conference of Bishops of the act of Excommunication of Mr Clifford Garcia and by act of canon law the same act falls upon him. Thergfore he has been suspended from all functions as a priest from this day I date being the 13ft December 2018. His celebret will be surrended : I.D. Number: T8P140870-7EP He has no authority to say Mass at the Our Mother of Perpetual Help and the Child Jesus. The conference of bishops will meet in lgIarch 2019 in the Philippines and the case will be fully heard by the conference of bishops'before the Superior General and Vicar Judge and the case will be fully decided. Their fore, Fr Allan Garcia is to take over Mass without interference at Our Mother of Perpetual Help and the Child Jesus until otherwise decided by *y office. Suspended Fr Ricky O Alcantara has spoken out against the Superior General in telling lies, untruth and hatred against the Archbishop & Superior General and brought the said office by his actions in to di violation of Canon Law. o' Given s 13th day of the Month of December in the year of our xx Most illu Lord James Atkinson *ffflY His Eminence, ArchbiSE-op of Birmingham & Dudley.