Private-Sector Involvement in Virginia's Nineteenth-Century Transportation Improvement Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds Rockingham County

BIRDS OF ROCKINGHAM COUNTY VIRGINIA Clair Mellinger, Editor Rockingham Bird Club o DC BIRDS OF ROCKINGHAM COUNTY VIRGINIA Clair Mellinger, Editor Rockingham Bird Club November 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................1 THE ENVIRONMENT....................................................................3 THE PEOPLE AND THE RECORDS........................................11 THE LOCATIONS........................................................................23 DEFINITIONS AND EXPLANATIONS......................................29 SPECIES ACCOUNTS...............................................................33 LITERATURE CITED................................................................ 113 INDEX...........................................................................................119 PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE AMERICAN GOLDFINCHES ON THE FRONT AND BACK COVER WERE GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY JOHN TROTT. The American Goldfinch has been used as the emblem for the Rockingham Bird Club since the club’s establishment in 1973. Copyright by the Rockingham Bird Club November 1998 FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is the product and a publication of the Rockingham Bird Club. It is a compilation of many historical and more recent records of bird sightings in Rockingham County. The primary purpose of the book is to publish Rockingham County bird records that may otherwise be unavailable to the general public. We hope that these records will serve a variety of useful purposes. For example, we hope that it will be useful to new (and experienced) birders as a guide to when and where to look for certain species. Researchers may find records or leads to records of which they were unaware. The records may support or counterbalance ideas about the change in species distribution and abundance. It is primarily a reference book, but fifty years from now some persons may even find the book interesting to read. In the Records section we have listed some of the persons who contributed to this book. -

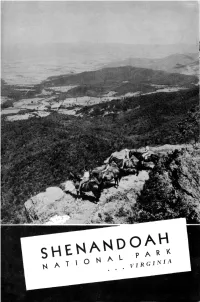

Shenandoah National Park Project Virginia

SHENANDOAH NATIONAL PARK PROJECT VIRGINIA White Oak Canyon UNITED STATES SHENANDOAH NATIONAL PARK PROJECT DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary In the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director national park in the Virginia section of the Blue Ridge Mountains was authorized by an act of Congress approv A ed May 22, 1926. The act specified that when title to 250,000 acres of a tract of land approved by the Secretary of the Interior should be vested in the United States, it would constitute a national park dedicated and set apart for the benefit and enjoyment of the people, and the Government would VIRGINIA STATE COMMISSION proceed with the installation of accommodations for visitors, ON the development of an adequate road and trail system, the CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT stocking of fishing streams, and the inauguration of an educa William E. Carson, Chairman tional service to acquaint the public with the historical back ground and natural beauty of this famous region. Upon the passage of the act, the State of Virginia, through its Commission on Conservation and Development, im mediately began the work of acquiring the money to purchase SHENANDOAH NATIONAL PARK PROJECT the necessary land. This was a tremendous undertaking as the approved area was made up of thousands of parcels of privately VIRGINIA owned land. Funds were raised through State appropriations, contributions from citizens of Virginia, and from outside sources. The work moved forward with all possible expediency until the period of general depression set in, and it became increasingly difficult to obtain funds. -

History of Virginia

14 Facts & Photos Profiles of Virginia History of Virginia For thousands of years before the arrival of the English, vari- other native peoples to form the powerful confederacy that con- ous societies of indigenous peoples inhabited the portion of the trolled the area that is now West Virginia until the Shawnee New World later designated by the English as “Virginia.” Ar- Wars (1811-1813). By only 1646, very few Powhatans re- chaeological and historical research by anthropologist Helen C. mained and were policed harshly by the English, no longer Rountree and others has established 3,000 years of settlement even allowed to choose their own leaders. They were organized in much of the Tidewater. Even so, a historical marker dedi- into the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes. They eventually cated in 2015 states that recent archaeological work at dissolved altogether and merged into Colonial society. Pocahontas Island has revealed prehistoric habitation dating to about 6500 BCE. The Piscataway were pushed north on the Potomac River early in their history, coming to be cut off from the rest of their peo- Native Americans ple. While some stayed, others chose to migrate west. Their movements are generally unrecorded in the historical record, As of the 16th Century, what is now the state of Virginia was but they reappear at Fort Detroit in modern-day Michigan by occupied by three main culture groups: the Iroquoian, the East- the end of the 18th century. These Piscataways are said to have ern Siouan and the Algonquian. The tip of the Delmarva Penin- moved to Canada and probably merged with the Mississaugas, sula south of the Indian River was controlled by the who had broken away from the Anishinaabeg and migrated Algonquian Nanticoke. -

Addendum No. 2

Addendum No. 2 Issue Date: 22 May 2017 To: Bidding Contractors - Plan Holders Project: Blue Ridge (Crozet) Tunnel Rehabilitation and Trail Project Nelson County Board of Supervisors The following items are being issued here for clarification, addition or deletion and have been incorporated into the Construction Documents and Project Manual, and shall be included as part of the bid documents. All Contractors shall acknowledge this Addendum No. 2 in the Bid Form. Failure of acknowledgment may result in rejection of your bid. All Bidders shall be responsible for seeing that their subcontractors are properly apprised of the contents of this addendum. BID DATE AND TIME: 1. The sign in sheet from the pre-bid meeting held on Friday May 12 th is included with Addenda 2. 2. At this time, the bid opening remains May 31 st at 2.00 PM. CLARIFICATIONS / CONTRACTOR QUESTIONS: 1. Q: The unit of measurement for the aggregate base material is in cubic yards. Can the units be revised to reflect the number of tons? A: Section 607.12 Unit Costs and Measures provides for the acceptable units for measurement. The quantity reflected in the bid form is based upon the area x thickness of the material. Please note that the volume is measured as “in-place and does not account for any volumetric loss due to compaction. The conversion from cubic yards to tons is based upon the unit weight of the material. For example, assuming a unit weight of 130 lbs/ft 3, which may be considered normal for VDOT 21B material, the conversion to tons would be 1 CY x (27 ft 3 / yd 3) x (130 lbs/ft 3) x (1 ton/2000 lbs). -

Mm Wttmn, the Shenandoah Valley Became an Artery of Critical Impor Soil Forest in the South Section of the Park

Shenandoah NATIONAL PARK VIRGINIA mm wttMN, The Shenandoah Valley became an artery of critical impor soil forest in the south section of the park. The characteristically tance during the War Between the States. General Jackson's dwarfed appearance of the deciduous trees overtopped by pine Shenandoah valley campaign is recognized as a superb example of military serves to distinguish the dry-soil forest from the moist-soil tactics. The mountain gaps within the park were strategically forest which predominates in the park. NATIONAL PARK important and were used frequently during these campaigns. Certain sections of the park support a variety of shrubs. The idea for a national park in the Southern Appalachian Notable among these are the azalea, the wild sweet crabapple, The Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia are famed for their Mountains originated in the early 1920's. In succeeding years, and the hawthorn which bloom in May, followed in summer by scenic loveliness, romantic setting, and historical association. the State and people of Virginia, together with public-spirited the ninebark, Jersey-tea, and the sumac. During late May and In the heart of these lofty mountains is the Shenandoah Na conservationists from other parts of the United States, purchased June the mountain-laurel transforms whole mountainsides into tional Park. Its majestic tree-covered peaks reach elevations of 176,430 acres of Blue Ridge Mountain lands. This area was a mass of bloom. more than 4,000 feet above the sea. Much of the time these deeded to the Federal Government for administration and Trees with a profusion of conspicuous blossoms include development as a national park in 1935. -

Shenandoah National Park U.S

National Park Service Shenandoah National Park U.S. Department of the Interior Park Emergency Number (800) 732-0911 01/13 Big Meadows Road and Trail Map Park Information recording: (540) 999-3500 www.nps.gov/shen You’llYou’ll findfind thesethese trailtrail markersmarkers at aallll ttrailheadsrailheads aandnd inintersections.tersections. TThehe metametall bbandsands aarere stamstampedped witwithh didirectionalrectional andand mileagemileage information.information. d a o R e r i F r e v i R il Tra e s op o Lo R er iv R se o R Observation Point Dark Hollow Falls Trail – 1.4 miles round trip; very steep; 70' waterfall. Pets are not allowed. Story of the Forest Trail – 1.8-mile easy circuit that passes through forest and connects with paved walkway. From the Byrd Visitor Center front exit: turn right, follow sidewalk to trail entrance. At paved walkway turn left to return to visitor center, or to avoid pavement, retrace steps. Pets are not allowed. Lewis Falls Trail – 3.3-mile circuit from amphitheater to observation point, returning * via Appalachian Trail, or 2 miles round trip from Skyline Drive. 81’ waterfall. Moderate with steep, rocky areas; one stream crossing. Rose River Loop Trail – 4-mile circuit from Fishers Gap. Moderate, shady trail with stream, cascades, waterfall. Note: Round trip hikes proceed to a destination and return by the same route. Circuit hikes begin and end at the same point without retracing steps. * Horses are allowed only on yellow-blazed fire roads and trails. Leave No Trace Preservation through education: building awareness, appreciation, and most of all, respect for our public recreation places. -

Nomination Form

VLR Listed: 12/4/1996 NRHP Listed: 4/28/1997 NFS Form 10-900 ! MAR * * I99T 0MB( No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) .^^oTT^Q CES United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Skyline Drive Historic District other name/site number: N/A 2. Location street & number: Shenandoah National Park (SHEN) not for publication: __ city/town: Luray vicinity: x state: VA county: Albemarle code: VA003 zip code: 22835 Augusta VA015 Greene VA079 Madison VA113 Page VA139 Rappahannock VA157 Rockingham VA165 Warren VA187 3. Classification Ownership of Property: public-Federal Category of Property: district Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 9 8 buildings 8 3 sites 136 67 structures 22 1 objects 175 79 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: none Name of related multiple property listing: Historic Park Landscapes in National and State Parks 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x _ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _x _ meets __^ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant x nationally __ statewide __ locally. ( __ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) _____________ Signature of certifying of ficial Date _____ ly/,a,-K OAJ. -

Shenandoah N a T > ° N a Vjrginia 1

SHENANDOAH N A T > ° N A VJRGINIA 1 . SHENANDOAH 'T'HE Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia are famed in song and tradition for their scenic loveliness, romantic setting, and historical as sociation. In the heart of these mountains is the Shenandoah National Park, established in 1935, the first wilderness area east of the Mis sissippi to be created a national park. Comprising 182,854 acres, the park extends for 75 miles in a narrow strip along the crest of the Blue Ridge from Front Royal on the northeast to the vicinity of Waynesboro on the southeast. The altitude varies from 600 feet above sea level at the north entrance to 4,049 feet at the summit of Hawksbill Mountain. The Skyline Drive It is for the far-reaching views from the Skyline Drive that the park is most widely known. The drive, macadamized and smooth, with an easy gradient and wide, sweeping curves, unfolds to view innumerable sweeping pano ramas of lofty peaks, forested ravines, meander ing streams, and the green and brown patchwork A TYPICAL SECTION OF THE FAMOUS SKYLINE DRIVE fields of the valley farms below. SHOWING THE EASY GRADIENT AND FLOWING CURVES. Virginia Conservation Commission Photo Built at a cost of more than $4,500,000, the famous 97-mile scenic highway traverses the LATE AFTERNOON ON SKYLINE DRIVE. KAWKSBILL, HIGH entire length of the park along the backbone of EST POINT IN THE PARK, IS SILHOUETTED IN THE DISTANCE. the Blue Ridge from Front Royal to Jarman Virginia State Chamber of Commerce Photo Gap, where it connects with the 485-mile Blue Ridge Parkway, now under construction, that will link Shenandoah National Park with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee and North Carolina. -

Geology of the Elkton Area Virginia

Geology of the Elkton area Virginia GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 230 Geology of the Elkton area Virginia By PHILIP B. KING GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 230 A detailed report on an area containing interesting problems of stratigraphy', structure, geomorphology, and economic geology UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1950 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $1.75 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract-- _ ________________________________________ 1 Stratigraphy—Continued Introduction. ______________________________________ 1 Cambrian system—Continued Previous work. _ ____________________________________ 2 Elbrook dolomite.________-_____._--_-__-__. 32 Present work. ______________________________________ 3 Name._ _____________-_-_-____---_____- 32 Acknowledgments. _________________________________ 3 Outcrop.____-___-------_--___----.-___ 32 Geography.. _ ______________________________________ 4 Character, _____________________________ 32 Stratigraphy _______________________________________ 6 Age_.____-_..-__-_---_--___------_-_._ 32 Pre-Cambrian rocks__ . __________________________ 7 Residuum of Elbrook dolomite ___________ 33 Injection complex. __________________________ 8 Stratigraphic relations-__________________ 33 Name. _ ----_-______----________-_-_-__ 8 Conococheague limestone.___________________ 33 Outcrop. ______________________________ -

National Park'virginia

NATIONAL PARK'VIRGINIA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Newton B. Drury, Director The Shenandoah Valley became an artery of critical impor Certain sections of the park support a variety of shrubs. Shenandoah tance during the War between the States. General Jackson's Notable among these are the azalea, the wild sweet crabapple, valley campaign is recognized as a superb example of military- and the hawthorn which bloom in May, followed by the NATIONAL PARK tactics. The mountain gaps within the park were strategically ninebark, Jersey-tea, and the sumac of summer. During late May important and were used frequently during these campaigns. and June the mountain-laurel transforms whole mountainsides The Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia are famed for their The idea for a national park in the Southern Appalachian into a mass of bloom. scenic loveliness, romantic setting, and historical association. Mountains originated in the early 1920's. In succeeding years, Trees with a profusion of conspicuous blossoms include In the heart of these lofty mountains is the Shenandoah the State and people of Virginia, together with public-spirited cherry, eastern redbud, flowering dogwood, tuliptree, American National Park. Its majestic tree-covered peaks reach elevations conservationists from other parts of the United States, purchased chestnut, and black locust. of more than 4,000 feet above the sea. Much of the time these 176,430 acres of Blue Ridge Mountain lands. This area was As they bloom and leaf out, the deciduous trees produce a peaks are softened by a faint blue haze from which the moun deeded to the Federal Government for administration and de pageant of color in the spring which is surpassed only by the tains get their name. -

AARP's Guide to Shenandoah National Park

12/22/2020 Things to Know About Visiting Shenandoah National Park AARP's Guide to Shenandoah National Park Cruise scenic Skyline Drive, explore mountain trails and find serenity at this Virginia treasure by Ken Budd, AARP, Updated November 2, 2020 | Comments: 0 JON BILOUS/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO En español | Gushing waterfalls. Rolling mountains. Granite peaks. Lush valleys. Ninety-plus streams. Fog oceans that tumble over the Blue Ridge Mountains. Animals and wildflowers aplenty. With such an abundance of natural beauty, Shenandoah National Park (SNP) ranks as one of Virginia's wildest yet most serene destinations. Author Bill Bryson calls it “possibly the most wonderful national park I have ever been in." Native Americans wandered this area for millennia to hunt, gather food and collect materials for stone tools ("Shenandoah” is a Native American word that some historians believe means “daughter of the stars"). European hunters and trappers arrived in the 1700s, followed by settlers and entrepreneurs who launched farming, logging, milling and mining operations. In the early 1900s, inspired by the popularity of Western national parks, Virginia politicians and businessmen pushed for a park in the East, and President Calvin Coolidge signed legislation authorizing SNP in 1926. Roughly 465 families had to leave their homes after the state of Virginia acquired the land, but a few stubborn mountaineers refused to go, living the rest of their lives in the thick woods. In 1931, the federal highway department began building SNP's signature attraction, 105-mile Skyline Drive, which runs north to south through the length of the park. Two years later, the Civilian Conservation Corps — one of President Franklin D. -

Acidic Deposition Impacts on Natural Resources in Shenandoah National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Northeast Region Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Acidic Deposition Impacts on Natural Resources in Shenandoah National Park Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2006/066 ON THE COVER Staunton River watershed, in the central section of Shenandoah National Park. Staunton River is one of the watersheds included in the long-term watershed research and monitoring program maintained by the Shenandoah Watershed Study. Photograph by: Rick Webb, Projects Coordinator, Shenandoah Watershed Study. Acidic Deposition Impacts on Natural Resources in Shenandoah National Park Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR—2006/066 Bernard J. Cosby, James R. Webb, James N. Galloway, and Frank A. Deviney Department of Environmental Sciences University of Virginia Clark Hall P.O. Box 400123 Charlottesville, VA 22904-4123 November 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Northeast Region Philadelphia, Pennsylvania The Northeast Region of the National Park Service (NPS) comprises national parks and related areas in 13 New England and Mid-Atlantic states. The diversity of parks and their resources are reflected in their designations as national parks, seashores, historic sites, recreation areas, military parks, memorials, and rivers and trails. Biological, physical, and social science research results, natural resource inventory and monitoring data, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences related to these park units are disseminated through the NPS/NER Technical Report (NRTR) and Natural Resources Report (NRR) series. The reports are a continuation of series with previous acronyms of NPS/PHSO, NPS/MAR, NPS/BSO-RNR, and NPS/NERBOST. Individual parks may also disseminate information through their own report series.