An Outbreak of Suspected Tick Paralysis in One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Kir) Channels in Tick Salivary Gland Function Zhilin Li Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 3-26-2018 Characterizing the Physiological Role of Inward Rectifier Potassium (Kir) Channels in Tick Salivary Gland Function Zhilin Li Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Zhilin, "Characterizing the Physiological Role of Inward Rectifier Potassium (Kir) Channels in Tick Salivary Gland Function" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4638. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4638 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARACTERIZING THE PHYSIOLOGICAL ROLE OF INWARD RECTIFIER POTASSIUM (KIR) CHANNELS IN TICK SALIVARY GLAND FUNCTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Entomology by Zhilin Li B.S., Northwest A&F University, 2014 May 2018 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family (Mom, Dad, Jialu and Runmo) for their support to my decision, so I can come to LSU and study for my degree. I would also thank Dr. Daniel Swale for offering me this awesome opportunity to step into toxicology filed, ask scientific questions and do fantastic research. I sincerely appreciate all the support and friendship from Dr. -

Toxicological Testing in Large Animals

Toxicological Testing in Large Animals Toxic causes of ill health and death in production animals are numerous. Toxin testing requires a specific toxin to be nominated as there is no suite of tests that covers all possibilities. Toxin testing is inherently expensive, requires specific sample types and false negatives can occur; for instance the toxin may have been eliminated from the body or be undetectable, but clinical signs may persist. Gribbles Veterinary Pathology can offer specific testing for a range of toxic substances, however it is important to consider the specific sample requirements and testing limitations for each toxin when advising your clients. Many tests are referred to external laboratories and may have extended turnaround times. Please contact the laboratory if you need testing for a specific toxin not listed here; we can often source unusual tests as needed from our network of referral laboratories. Clinicians should also consider syndromes which may mimic intoxication such as hypocalcaemia, hypoglycaemia, hepatic encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathies and primary CNS diseases. Examples of intoxicants that can be tested are provided below. See individual tests in the Pricelist for sample requirements and costs. Biological control agents Heavy metals • 1080 (fluoroacetate) • Arsenic • Strychnine • Lead • Synthetic pyrethroids • Copper • Organophosphates • Selenium • Organochlorines • Zinc • Carbamates • Metaldehyde • Anticoagulant rodenticides (warfarin, pindone, coumetetryl, bromadiolone, difenacoum, brodifacoum) -

Neuromuscular Disorders Neurology in Practice: Series Editors: Robert A

Neuromuscular Disorders neurology in practice: series editors: robert a. gross, department of neurology, university of rochester medical center, rochester, ny, usa jonathan w. mink, department of neurology, university of rochester medical center,rochester, ny, usa Neuromuscular Disorders edited by Rabi N. Tawil, MD Professor of Neurology University of Rochester Medical Center Rochester, NY, USA Shannon Venance, MD, PhD, FRCPCP Associate Professor of Neurology The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition fi rst published 2011, ® 2011 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered offi ce: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial offi ces: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell The right of the author to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Information About Tick Paralysis? Adapted From: CDC

Peachtree Street NW, 15th Floor Atlanta, Georgia 30303-3142 Georgia Department of Public Health www.health.state.ga.us Tick Paralysis Q&A What is tick paralysis? Tick paralysis refers to acute onset of paralysis caused by a tick bite. The condition is primarily found in the Rocky Mountain and northwestern regions of the United States and is rare in Georgia. The number of cases per year is unknown because physicians are not required to report cases of tick paralysis to Public Health. How is tick paralysis spread? Tick paralysis results from a neurotoxin that is secreted in the saliva of certain ticks when they feed. The tick must be attached for several days. Person‐to‐person transmission of tick paralysis has not been documented. Who gets tick paralysis? Anyone who is bitten by a tick can get tick paralysis, but it most commonly affects children less than 10 years of age. What are the symptoms of tick paralysis? The symptoms of tick paralysis include weakness in the legs and arms, followed by paralysis beginning in the legs and moving upward. If unrecognized, tick paralysis may progress to respiratory failure and may be fatal in 10% of cases. What is the treatment for tick paralysis? Treatment for tick paralysis is simply removal of the tick. Once the tick is found and removed, the patient recovers fully, often within a matter of hours. It is often difficult to find the tick, which can be attached to the scalp and hidden in the hair. What can be done to prevent the spread of tick paralysis? There are no vaccines to prevent tick‐borne disease, so limiting exposure to ticks is very important. -

Tick Paralysis

April 26, 1996 / Vol. 45 / No. 16 325 Tick Paralysis — Washington, 1995 326 Update: Influenza Activity — United States and Worldwide, 1995–96 Season, and Composition of the 1996–97 Influenza Vaccine 330 Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis Outbreak on an HIV Ward — Madrid, Spain, 1991–1995 333 Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance — United States, Fourth Quarter, 1995 335 Notice to Readers Tick Paralysis — Washington, 1995 Tick Paralysisparalysis (tick— Continued toxicosis)—one of the eight most common tickborne diseases in the United States (1 )—is an acute, ascending, flaccid motor paralysis that can be con- fused with Guillain-Barré syndrome, botulism, and myasthenia gravis. This report summarizes the results of the investigation of a case of tick paralysis in Washington. On April 10, 1995, a 2-year-old girl who resided in Asotin County, Washington, was taken to the emergency department of a regional hospital because of a 2-day history of unsteady gait, difficulty standing, and reluctance to walk. Other than a recent his- tory of cough, she had been healthy and had not been injured. On physical examina- tion, she was afebrile, alert, and active but could stand only briefly before requiring assistance. Cranial nerve function was intact. However, she exhibited marked extrem- ity and mild truncal ataxia, and deep tendon reflexes were absent. She was admitted with a tentative diagnosis of either Guillain-Barré syndrome or postinfectious polyradiculopathy. Within several hours of hospitalization, she had onset of drooling and tachypnea. A nurse incidentally detected an engorged tick on the girl’s hairline by an ear and re- moved the tick. -

Tick-Borne Disease Prevention Program

Tick-Borne Disease Prevention Program INTRODUCTION Hudson Valley Community College employees working outdoors, especially in areas with tall grasses, shrubs, low hanging branches, or leaf mold are susceptible to being bitten by a tick. There are several diseases which can be carried by ticks, with the most well-known in this area being Lyme disease. This document provides information about tick-borne illnesses, how to prevent tick bites and what to do if you find a tick on you. BACKGROUND Lyme Disease is a bacterial infection that can be caused by the transmission of the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria from the bite of an infected deer tick. Deer ticks primarily transmit the Lyme Disease bacteria in the late Spring or early Summer while they are in their nymphal stage of development, but they can carry the bacteria in their larval, nymph, or adult stages at almost any time of the year. Ticks are picked up when a person’s clothing or hair brushes a leaf or other object they are on. Ticks do not jump, crawl, or fall onto a person. Once picked up, they will crawl until they find a favorable site to feed. Often they will find a spot at the back of a knee, near the hairline, or behind the ears. Deer ticks are much smaller than common dog ticks. The nymphal stage tick is usually not much larger than the head of a pin and can easily go unnoticed if attached to a person. Not all deer ticks are infected with the bacteria that cause Lyme disease. -

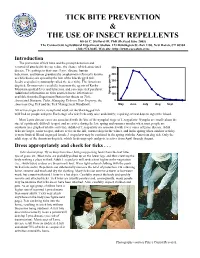

Tick Bite Prevention & the Use of Insect Repellents

TICK BITE PREVENTION & THE USE OF INSECT REPELLENTS Kirby C. Stafford III, PhD (Revised June 2005) The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, 123 Huntington St.-Box 1106, New Haven, CT 06504 (203) 974-8485, Web site: http://www.caes.state.ct.us Introduction The prevention of tick bites and the prompt detection and removal of attached ticks can reduce the chance of tick-associated 500 disease. The pathogens that cause Lyme disease, human babesiosis, and human granulocytic anaplasmosis (formerly known 400 as ehrlichiosis) are spread by the bite of the blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis (commonly called the deer tick). The American 300 dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis, transmits the agents of Rocky 200 Mountain spotted fever and tularemia, and can cause tick paralysis. Additional information on ticks and tick-borne infections is ha per Nymphs 100 available from the Experiment Station fact sheets on Tick- Associated Diseases, Ticks, Managing Ticks on Your Property, the 0 American Dog Tick and the Tick Management Handbook. May June July Aug Sept All active stages (larva, nymph and adult) of the blacklegged tick will feed on people and pets. Each stage of a tick feeds only once and slowly; requiring several days to ingest the blood. Most Lyme disease cases are associated with the bite of the nymphal stage of I. scapularis. Nymphs are small (about the size of a pinhead), difficult to spot, and are active during the late spring and summer months when most people are outdoors (see graph of relative activity). Adults of I. scapularis are associated with fewer cases of Lyme disease. -

VANDER VELDE and BRIAN VANDER VELDE Biological Consultants, Marshall Islands; P

Micronesica 2013-01: 1–26 Known and potential ticks and tick-borne pathogens of Micronesia1 NANCY VANDER VELDE AND BRIAN VANDER VELDE Biological Consultants, Marshall Islands; P. O. Box 1603, Majuro, MH 96960 [email protected] Abstract—Ticks have long been known to be the vectors of diseases, to both humans and animals. Yet very little work has been done regarding tick species found in Micronesia, and much of that is now decades old. Many parts of Micronesia have long undergone considerable change by outside influences and hence the natural and social environments have undergone major upheavals. Ticks as vectors of veterinary disease have long been documented in Micronesia, but ticks connected with human disease are often presumed not to exist. Hence another look would seem justified. This paper provides an initial review of information on tick species reported from Micronesia. Some diseases that such ticks transmit are presented, along with some hypothetical consideration of other diseases potentially associated with ticks of Micronesia. As this information on the ecology of ticks in Micronesia and the environments and circumstances allowing for the possibility of transmission of disease to humans come together, there emerges an intriguing picture of an often-overlooked part of the environment in which humans live in Micronesia. Introduction TICKS In recent years it has become more and more apparent that ticks play a major part in the transmission of diseases. Ticks are hence now considered “second only to mosquitoes as vectors of disease-causing agents in humans and are the most important arthropod transmitting pathogens to domestic and wild animals,” and to “transmit a greater variety of pathogenic micro-organisms than any other arthropod vector group” including such pathogens as “protozoa, rickettsiae, spirochaetes and viruses” (AFPMB 1998, Estrada-Peña & Jongejan 1999, You et al. -

Peripheral Nervous System Complications of Infectious Diseases

Peripheral Nervous System Complications of Infectious Diseases A. Arturo Leis, MD John J. Halperin, MD Taylor B. Harrison, MD Dianna Quan, MD AANEM 59th Annual Meeting Orlando, Florida Copyright © October 2012 American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine 2621 Superior Drive NW Rochester, MN 55901 Printed by Johnson Printing Company, Inc. 1 Dr. Quan has indicated that her material references an “off-label” use of a commercial product. Please be aware that some of the medical devices or pharmaceuticals discussed in this handout may not be cleared by the FDA or cleared by the FDA for the specific use described by the authors and are “off-label” (i.e., a use not described on the product’s label). “Off-label” devices or pharmaceuticals may be used if, in the judgment of the treating physician, such use is medically indicated to treat a patient’s condition. Information regarding the FDA clearance status of a particular device or pharmaceutical may be obtained by reading the product’s package labeling, by contacting a sales representative or legal counsel of the manufacturer of the device or pharmaceutical, or by contacting the FDA at 1-800-638-2041. 2 Peripheral Nervous System Complications of Infectious Diseases Table of Contents Course Committees & Course Objectives 4 Faculty 5 Neuromuscular Manifestations of West Nile and Polio Virus Infection 7 A. Arturo Leis, MD Peripheral Nervous System Complications of Neuroborreliosis 15 John J. Halperin, MD Polyneuropathies Associated With Infectious Disease 21 Taylor B. Harrison, MD Varicella Zoster Virus and Postherpetic Neuralgia: A New Era? 31 Dianna Quan, MD CME Questions 35 No one involved in the planning of this CME activity had any relevant financial relationships to disclose. -

Surviving Tick Paralysis

Copyright All contents copyright (c) 2011 by Gordon Veterinary Hospital. All rights reserved. No part of this document or the related files may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Limit of Liability and Disclaimer of Warranty The publisher has used its best efforts in preparing this book, and the information provided herein is provided “as is.” Gordon Veterinary Hospital makes no representation or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaims any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose and shall in no event be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. Trademarks This book identifies product names and services known to be trademarks, registered trademarks, or service marks of their respective holders. They are used throughout this book in an editorial fashion only. In addition, terms suspected of being trademarks, registered trademarks, or service marks have been appropriately capitalized, although Gordon Veterinary Hospital cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark, registered trademark, or service mark. Gordon Veterinary Hospital is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. Page II Table of Contents Introduction 2 Emergency? 3 Tick Paralysis Explained 4 How Could This Happen to My Pet? 7 How Do We Diagnose Tick Paralysis 8 What To Do If You Are Suspicious Of Tick Paralysis 9 Treating Tick Paralysis 11 Preventing Tick Paralysis 16 Page 1 Introduction Hello and thanks for downloading my ebook on Tick Paralysis. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics refer to figures and those in bold refer to tables and boxes abacavir (ABC) 116 acute inflammatory demyelinat- alveolar hydatid disease 232 abdomen, fever 27, 187 ing polyneuropathy ascariasis 209, 210 abdominal pain 3–4, 44 (AIDP) 262–3 cestode infections 206 abortion, malaria 61 acute motor axonal neuropathy cutaneous larva migrans 318 abscess (AMAN) 263 cysticercosis 206 amoebic 186, 187 acute pneumonia 234 filariasis 144, 145 guinea worm 326 differential diagnosis 235–6 giardiasis 200 melioidosis 309 signs 234–5 hookworm 211 paratyphoid 286 symptoms 234 hydatid cyst disease 229 pyogenic 188 acute pulmonary loiasis 147 spinal epidural 265 histoplasmosis 328 strongyloidiasis 324 typhoid 282 acute schistosomiasis 162–3, 166–7, treatment of immigrants 371 see also liver abscess, amoebic 168 trichuriasis 212 Acanthamoeba species 185 Addison’s disease 34, 340 tropical pulmonary achlorhydria 195 adrenaline 343, 344, 357 eosinophilia 244–5 aciclovir 260 adult respiratory distress syndrome visceral larva migrans 213 acidaemia, malaria 64 (ARDS) 307 alcohol abuse 225 Actinomycetes 330 Aedes 142, 295, 299 hypertension 352–4 actinomycosis 91, 314 Aedes aegypti 296, 299 alcoholic psychosis 378 active immunization 269 Aedes albopictus 296 allergens activity, reduced 353 Aedes mosquitoes 245, 260, 287, asthma 355–6 acute bacterial pneumonia 14 288, 296, 299 avoidance 356 acute Chagas’ disease 155 affective (mood) changes 362 alpha-fetoprotein 225 acute dermatolymphangioadenitis aflatoxins 223, 228 alveolar hydatid -

Common Ticks of Oklahoma and Tick-Borne Diseases

Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service EPP-7001 Common Ticks of Oklahoma and Tick-Borne Diseases Justin L. Talley Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Fact Sheets Associate Professor of Entomology & Plant Pathology are also available on our website at: http://osufacts.okstate.edu Deborah C. Jaworski Assistant Professor of Entomology & Plant Pathology Bruce H. Noden Assistant Professor of Entomology and Plant Pathology Katherine M. Kocan Regents Professor & Walter R. Stitlington Endowed Chair of Food Animal Research Department of Veterinary Pathobiology Susan Little Regents Professor & Krull-Ewing Chair in Veterinary Parasitology Department of Veterinary Pathobiology Ticks transmit a greater diversity of disease-causing or- ganisms to wildlife, domesticated animals and humans than any other vector arthropod. Ticks are also known to cause paralysis, toxicosis and allergic reactions. Tick bites can cause dermatitis (an itching, swelling, inflamed condition of the skin) on the host. In animals, the loss of blood can cause second- ary anemia and sometimes death. Ticks have four “developmental” or life cycle stages known as the egg, larva, nymph and adult (Figure 1). Larvae are sometimes called seed ticks and are slightly smaller than Figure 1: General life cycle of ticks. www.cdc.gov a pin head. Nymphs are larger than a pin head. Adults and nymphs have four legs, while larvae have six legs. Ticks are more closely related to spiders than insects. ance than unfed females, the males and all other life stages. Ticks can be distinguished from insects because their bodies These females are much larger, and therefore more visible are not divided into distinct segments. A distinct head is lack- than the other life stages seen on hosts.