Common Ticks of Oklahoma and Tick-Borne Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tick-Borne Diseases Primary Tick-Borne Diseases in the Southeastern U.S

Entomology Insect Information Series Providing Leadership in Environmental Entomology Department of Entomology, Soils, and Plant Sciences • 114 Long Hall • Clemson, SC 29634-0315 • Phone: 864-656-3111 email:[email protected] Tick-borne Diseases Primary tick-borne diseases in the southeastern U.S. Affecting Humans in the Southeastern United Disease (causal organism) Tick vector (Scientific name) States Lyme disease Black-legged or “deer” tick (Borrelia burgdorferi species (Ixodes scapularis) Ticks are external parasites that attach themselves complex) to an animal host to take a blood meal at each of Rocky Mountain spotted fever American dog tick their active life stages. Blood feeding by ticks may (Rickettsia rickettsii) (Dermacentor variabilis) lead to the spread of disease. Several common Southern Tick-Associated Rash Lone star tick species of ticks may vector (transmit) disease. Many Illness or STARI (Borrelia (Amblyomma americanum) tick-borne diseases are successfully treated if lonestari (suspected, not symptoms are recognized early. When the disease is confirmed)) Tick-borne Ehrlichiosis not diagnosed during the early stages of infection, HGA-Human granulocytic Black-legged or “deer” tick treatment can be difficult and chronic symptoms anaplasmosis (Anaplasma (Ixodes scapularis) may develop. The most commonly encountered formerly Ehrlichia ticks in the southeastern U.S. are the American dog phagocytophilum) tick, lone star tick, blacklegged or “deer” tick and HME-Human monocytic Lone star tick brown dog tick. While the brown dog tick is notable Ehrlichiosis (Amblyomma americanum) because of large numbers that may be found indoors (Ehrlichia chafeensis ) American dog tick when dogs are present, it only rarely feeds on (Dermacentor variabilis) humans. -

(Kir) Channels in Tick Salivary Gland Function Zhilin Li Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 3-26-2018 Characterizing the Physiological Role of Inward Rectifier Potassium (Kir) Channels in Tick Salivary Gland Function Zhilin Li Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Zhilin, "Characterizing the Physiological Role of Inward Rectifier Potassium (Kir) Channels in Tick Salivary Gland Function" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4638. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4638 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARACTERIZING THE PHYSIOLOGICAL ROLE OF INWARD RECTIFIER POTASSIUM (KIR) CHANNELS IN TICK SALIVARY GLAND FUNCTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Entomology by Zhilin Li B.S., Northwest A&F University, 2014 May 2018 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family (Mom, Dad, Jialu and Runmo) for their support to my decision, so I can come to LSU and study for my degree. I would also thank Dr. Daniel Swale for offering me this awesome opportunity to step into toxicology filed, ask scientific questions and do fantastic research. I sincerely appreciate all the support and friendship from Dr. -

Toxicological Testing in Large Animals

Toxicological Testing in Large Animals Toxic causes of ill health and death in production animals are numerous. Toxin testing requires a specific toxin to be nominated as there is no suite of tests that covers all possibilities. Toxin testing is inherently expensive, requires specific sample types and false negatives can occur; for instance the toxin may have been eliminated from the body or be undetectable, but clinical signs may persist. Gribbles Veterinary Pathology can offer specific testing for a range of toxic substances, however it is important to consider the specific sample requirements and testing limitations for each toxin when advising your clients. Many tests are referred to external laboratories and may have extended turnaround times. Please contact the laboratory if you need testing for a specific toxin not listed here; we can often source unusual tests as needed from our network of referral laboratories. Clinicians should also consider syndromes which may mimic intoxication such as hypocalcaemia, hypoglycaemia, hepatic encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathies and primary CNS diseases. Examples of intoxicants that can be tested are provided below. See individual tests in the Pricelist for sample requirements and costs. Biological control agents Heavy metals • 1080 (fluoroacetate) • Arsenic • Strychnine • Lead • Synthetic pyrethroids • Copper • Organophosphates • Selenium • Organochlorines • Zinc • Carbamates • Metaldehyde • Anticoagulant rodenticides (warfarin, pindone, coumetetryl, bromadiolone, difenacoum, brodifacoum) -

Ixodes Scapularis) Affected Species: Humans PATHOBIOLOGY and VETERINARY SCIENCE • CONNECTICUT VETERINARY MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY

Tick Borne Diseases In New England Bullseye rash- common symptom of Lyme disease and STARI Skin lesions- common symptom of Tularemia Tularemia Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Agent: Rickettsia rickettsii Agent: Francisella tularensis Brown Dog Tick Symptoms: fever, “spotted” rash, headache, nausea, Symptoms: fever, skin lesions in people, vomiting, abdominal pain, muscle pain, lack of appetite, face and eyes redden and become (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) red eyes inflamed, chills, headache, exhaustion Affected Species: humans, dogs Affected Species: humans, rabbits, rodents, cats, dogs, sheep, many Dog Tick mammalian species (Dermacentor variabilis) Ehrlichiosis Agent: Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii Symptoms: fever, headache, chills, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, confusion, red eyes Affected Species: humans, dogs, cats Babesiosis Anaplasmosis Agent: Babesia microti Agent: Anaplasma phagocytophilum Symptoms: (many show none), fever, chills, sweats, Lone star tick Symptoms: fever, severe headache, muscle aches, headache, body aches, loss of appetite, nausea chills and shaking, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain Affected Species: humans (Amblyomma americanum) Affected Species: humans, dogs, horses, cows Borrelia miyamotoi Disease Agent: Borrelia miyamotoi Southern Tick-Associated Lyme Disease Symptoms: fever, chills, headache, body and joint Agent: Borrelia burgdorferi pain, fatigue Rash Illness (STARI) Symptoms: “bullseye” rash Affected Species: humans Agent: Borrelia lonestari (humans only), fever, aching joints, Symptoms: “bullseye” rash, fatigue, muscle pains, headache, fatigue, neurological headache involvement Affected Species: humans Affected Species: humans, Powassan Virus horses, dogs, many others Agent: Powassan Virus Symptoms: (many show none), fever, headache, vomiting, weakness, confusion, loss of coordination, Deer Tick speech difficulties, seizures (Ixodes scapularis) Affected Species: humans PATHOBIOLOGY AND VETERINARY SCIENCE • CONNECTICUT VETERINARY MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY. -

Tick-Borne Diseases in Maine a Physician’S Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC Photo)

tick-borne diseases in Maine A Physician’s Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC PHOTO) Nymph Nymph Nymph Adult Male Adult Male Adult Male Adult Female Adult Female Adult Female images not to scale know your ticks Ticks are generally found in brushy or wooded areas, near the DEER TICK DOG TICK LONESTAR TICK Ixodes scapularis Dermacentor variabilis Amblyomma americanum ground; they cannot jump or fly. Ticks are attracted to a variety (also called blacklegged tick) (also called wood tick) of host factors including body heat and carbon dioxide. They will Diseases Diseases Diseases transfer to a potential host when one brushes directly against Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted Ehrlichiosis anaplasmosis, babesiosis fever and tularemia them and then seek a site for attachment. What bites What bites What bites Nymph and adult females Nymph and adult females Adult females When When When April through September in Anytime temperatures are April through August New England, year-round in above freezing, greatest Southern U.S. Coloring risk is spring through fall Adult females have a dark Coloring Coloring brown body with whitish Adult females have a brown Adult females have a markings on its hood body with a white spot on reddish-brown tear shaped the hood Size: body with dark brown hood Unfed Adults: Size: Size: Watermelon seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed suMMer fever algorithM ALGORITHM FOR DIFFERENTIATING TICK-BORNE DISEASES IN MAINE Patient resides, works, or recreates in an area likely to have ticks and is exhibiting fever, This algorithm is intended for use as a general guide when pursuing a diagnosis. -

Neuromuscular Disorders Neurology in Practice: Series Editors: Robert A

Neuromuscular Disorders neurology in practice: series editors: robert a. gross, department of neurology, university of rochester medical center, rochester, ny, usa jonathan w. mink, department of neurology, university of rochester medical center,rochester, ny, usa Neuromuscular Disorders edited by Rabi N. Tawil, MD Professor of Neurology University of Rochester Medical Center Rochester, NY, USA Shannon Venance, MD, PhD, FRCPCP Associate Professor of Neurology The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition fi rst published 2011, ® 2011 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered offi ce: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial offi ces: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell The right of the author to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Information About Tick Paralysis? Adapted From: CDC

Peachtree Street NW, 15th Floor Atlanta, Georgia 30303-3142 Georgia Department of Public Health www.health.state.ga.us Tick Paralysis Q&A What is tick paralysis? Tick paralysis refers to acute onset of paralysis caused by a tick bite. The condition is primarily found in the Rocky Mountain and northwestern regions of the United States and is rare in Georgia. The number of cases per year is unknown because physicians are not required to report cases of tick paralysis to Public Health. How is tick paralysis spread? Tick paralysis results from a neurotoxin that is secreted in the saliva of certain ticks when they feed. The tick must be attached for several days. Person‐to‐person transmission of tick paralysis has not been documented. Who gets tick paralysis? Anyone who is bitten by a tick can get tick paralysis, but it most commonly affects children less than 10 years of age. What are the symptoms of tick paralysis? The symptoms of tick paralysis include weakness in the legs and arms, followed by paralysis beginning in the legs and moving upward. If unrecognized, tick paralysis may progress to respiratory failure and may be fatal in 10% of cases. What is the treatment for tick paralysis? Treatment for tick paralysis is simply removal of the tick. Once the tick is found and removed, the patient recovers fully, often within a matter of hours. It is often difficult to find the tick, which can be attached to the scalp and hidden in the hair. What can be done to prevent the spread of tick paralysis? There are no vaccines to prevent tick‐borne disease, so limiting exposure to ticks is very important. -

Tick Paralysis

April 26, 1996 / Vol. 45 / No. 16 325 Tick Paralysis — Washington, 1995 326 Update: Influenza Activity — United States and Worldwide, 1995–96 Season, and Composition of the 1996–97 Influenza Vaccine 330 Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis Outbreak on an HIV Ward — Madrid, Spain, 1991–1995 333 Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance — United States, Fourth Quarter, 1995 335 Notice to Readers Tick Paralysis — Washington, 1995 Tick Paralysisparalysis (tick— Continued toxicosis)—one of the eight most common tickborne diseases in the United States (1 )—is an acute, ascending, flaccid motor paralysis that can be con- fused with Guillain-Barré syndrome, botulism, and myasthenia gravis. This report summarizes the results of the investigation of a case of tick paralysis in Washington. On April 10, 1995, a 2-year-old girl who resided in Asotin County, Washington, was taken to the emergency department of a regional hospital because of a 2-day history of unsteady gait, difficulty standing, and reluctance to walk. Other than a recent his- tory of cough, she had been healthy and had not been injured. On physical examina- tion, she was afebrile, alert, and active but could stand only briefly before requiring assistance. Cranial nerve function was intact. However, she exhibited marked extrem- ity and mild truncal ataxia, and deep tendon reflexes were absent. She was admitted with a tentative diagnosis of either Guillain-Barré syndrome or postinfectious polyradiculopathy. Within several hours of hospitalization, she had onset of drooling and tachypnea. A nurse incidentally detected an engorged tick on the girl’s hairline by an ear and re- moved the tick. -

Tick-Borne Disease Prevention Program

Tick-Borne Disease Prevention Program INTRODUCTION Hudson Valley Community College employees working outdoors, especially in areas with tall grasses, shrubs, low hanging branches, or leaf mold are susceptible to being bitten by a tick. There are several diseases which can be carried by ticks, with the most well-known in this area being Lyme disease. This document provides information about tick-borne illnesses, how to prevent tick bites and what to do if you find a tick on you. BACKGROUND Lyme Disease is a bacterial infection that can be caused by the transmission of the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria from the bite of an infected deer tick. Deer ticks primarily transmit the Lyme Disease bacteria in the late Spring or early Summer while they are in their nymphal stage of development, but they can carry the bacteria in their larval, nymph, or adult stages at almost any time of the year. Ticks are picked up when a person’s clothing or hair brushes a leaf or other object they are on. Ticks do not jump, crawl, or fall onto a person. Once picked up, they will crawl until they find a favorable site to feed. Often they will find a spot at the back of a knee, near the hairline, or behind the ears. Deer ticks are much smaller than common dog ticks. The nymphal stage tick is usually not much larger than the head of a pin and can easily go unnoticed if attached to a person. Not all deer ticks are infected with the bacteria that cause Lyme disease. -

An Outbreak of Suspected Tick Paralysis in One

Retour au menu ENTOMOLOGIE An outbreak of suspected tick paralysis M.T. Musa l in one-humped camels (Camelus O.M. Osman 2 I dromecfarius) in the Sudan MUSA (M.T.), OSMAN (O.M.). Suspicion d’un foyer de paralysie due HISTORY a,ux tiques chez le dromadaire (Camelus dromedarius) au Soudan. Revue Elev. Méd. vét. Pays trop., 1990,43 (4) : 505-510 Before the drought years 1983-l 984, came1 nomads used Un foyer de paralysie, probablement due aux tiques, a été découvert to spend the rainy seasons further north in the semi-arid sur des dromadaires (Camelus dromedurius) dans la région de Darfur, zone. As a result of drought pressures, the traditional au Soudan. entre les latitudes 11-12” N et les lonaitudes 24-25” E. Les movement belts shifted further south. Thus, the outbreak troupeauxse trouvaient dans des zones infestéesde tiques. Dix trou- peaux, totalisant 251 animaux d’âges différents, ont été concernés, sites were adopted as dry season grazing areas by the avec une mortalité de 34,3 p. 100. 6Ïr a noté les symptômes suivants : came1 nomads and other herders. incoordination, démarche hésitante et décubitus, suivis soit par la mort, soit par la guérison. Des adultes de Zfyulomma et des nymphes, In 1987, because of the poor rains in the north, the came1 et des adultes de Rhipicephalus ont été suspectés comme agents res- nomads returned to their usual dry season residences ponsable de la maladie. Des tiques nourries expérimentalement sur exceptionnally earlier (mid-October), shortly after late cobaye ont provoqué chez ce dernier une paralysie temporaire. -

Mechanisms Affecting the Acquisition, Persistence and Transmission Of

microorganisms Review Mechanisms Affecting the Acquisition, Persistence and Transmission of Francisella tularensis in Ticks Brenden G. Tully and Jason F. Huntley * Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, Toledo, OH 43614, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 September 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: Over 600,000 vector-borne disease cases were reported in the United States (U.S.) in the past 13 years, of which more than three-quarters were tick-borne diseases. Although Lyme disease accounts for the majority of tick-borne disease cases in the U.S., tularemia cases have been increasing over the past decade, with >220 cases reported yearly. However, when comparing Borrelia burgdorferi (causative agent of Lyme disease) and Francisella tularensis (causative agent of tularemia), the low infectious dose (<10 bacteria), high morbidity and mortality rates, and potential transmission of tularemia by multiple tick vectors have raised national concerns about future tularemia outbreaks. Despite these concerns, little is known about how F. tularensis is acquired by, persists in, or is transmitted by ticks. Moreover, the role of one or more tick vectors in transmitting F. tularensis to humans remains a major question. Finally, virtually no studies have examined how F. tularensis adapts to life in the tick (vs. the mammalian host), how tick endosymbionts affect F. tularensis infections, or whether other factors (e.g., tick immunity) impact the ability of F. tularensis to infect ticks. This review will assess our current understanding of each of these issues and will offer a framework for future studies, which could help us better understand tularemia and other tick-borne diseases. -

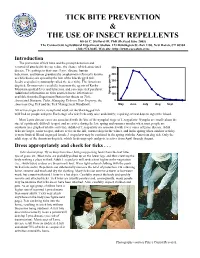

Tick Bite Prevention & the Use of Insect Repellents

TICK BITE PREVENTION & THE USE OF INSECT REPELLENTS Kirby C. Stafford III, PhD (Revised June 2005) The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, 123 Huntington St.-Box 1106, New Haven, CT 06504 (203) 974-8485, Web site: http://www.caes.state.ct.us Introduction The prevention of tick bites and the prompt detection and removal of attached ticks can reduce the chance of tick-associated 500 disease. The pathogens that cause Lyme disease, human babesiosis, and human granulocytic anaplasmosis (formerly known 400 as ehrlichiosis) are spread by the bite of the blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis (commonly called the deer tick). The American 300 dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis, transmits the agents of Rocky 200 Mountain spotted fever and tularemia, and can cause tick paralysis. Additional information on ticks and tick-borne infections is ha per Nymphs 100 available from the Experiment Station fact sheets on Tick- Associated Diseases, Ticks, Managing Ticks on Your Property, the 0 American Dog Tick and the Tick Management Handbook. May June July Aug Sept All active stages (larva, nymph and adult) of the blacklegged tick will feed on people and pets. Each stage of a tick feeds only once and slowly; requiring several days to ingest the blood. Most Lyme disease cases are associated with the bite of the nymphal stage of I. scapularis. Nymphs are small (about the size of a pinhead), difficult to spot, and are active during the late spring and summer months when most people are outdoors (see graph of relative activity). Adults of I. scapularis are associated with fewer cases of Lyme disease.