Property Law: Second Report on Land Registration Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAND REGISTRATION for the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY a Conveyancing Revolution

LAND REGISTRATION FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY A Conveyancing Revolution LAND REGISTRATION BILL AND COMMENTARY Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 9 July 2001 LAW COMMISSION H M LAND REGISTRY LAW COM NO 271 LONDON: The Stationery Office HC 114 The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. THE COMMISSIONERS ARE: The Honourable Mr Justice Carnwath CVO, Chairman Professor Hugh Beale Mr Stuart Bridge· Professor Martin Partington Judge Alan Wilkie QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers Her Majesty’s Land Registry, a separate department of government and now an Executive Agency, maintains the land registers for England and Wales and is responsible for delivering all land registration services under the Land Registration Act 1925. The Chief Land Registrar and Chief Executive is Mr Peter Collis The Solicitor to H M Land Registry is Mr Christopher West The terms of this report were agreed on 31 May 2001. The text of this report is available on the Internet at: http://www.lawcom.gov.uk · Mr Stuart Bridge was appointed Law Commissioner with effect from 2 July 2001. The terms of this report were agreed on 31 May 2001, while Mr Charles Harpum was a Law Commissioner. ii LAW COMMISSION HM LAND REGISTRY LAND REGISTRATION FOR THE TWENTY- FIRST CENTURY A Conveyancing Revolution CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: THE LAND REGISTRATION BILL AND -

Land Registry Annual Report and Accounts 2005/6 Creating a Comprehensive Land Register Readers of This Report

Land Registry Annual Report and Accounts 2005/6 Creating a comprehensive Land Register Readers of this report Her Majesty’s Land Registry academics in the field (Land Registry), established the professional and in 1862, is a government national press department in its own right, other government an executive agency and a departments and trading fund that makes no agencies including HM call on monies voted by Treasury and the Cabinet Parliament. By statute, it is Office required to ensure that its land registries overseas income from fees covers all the United Nations, of its expenditure. European Union and World Bank Land Registry comprises the those individuals in Registration of Title institutions with a Department, dealing with its professional interest in main business, and the much public sector smaller Land Charges and management. Agricultural Credits Departments. This report For readers of this report who deals with the departments are not familiar with Land separately but the accounts Registry terms, a glossary are given for Land Registry as has been provided at a whole. Appendix 10. This report is available for online viewing The Secretary of State for on our website at Constitutional Affairs and www.landregistry.gov.uk Lord Chancellor is the Minister responsible for Land Registry. This is the Chief If you would like this Land Registrar’s formal Annual Report and account to the Minister of Land Registry’s performance Accounts in a different against each of the objectives format including audio and key performance targets set by -

Report at a Glance

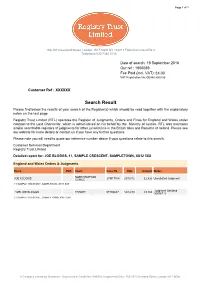

Page 1 of 2 153-157 Cleveland Street, London, W1T 6QW DX 134211 Tottenham Court Rd 2 Telephone 020 7380 0133 Date of search: 19 September 2016 Our ref : 1900089 Fee Paid (incl. VAT): £4.00 VAT Registration No: GB440 4009 96 Customer Ref : XXXXXX Search Result Please find below the results of your search of the Register(s) which should be read together with the explanatory notes on the last page. Registry Trust Limited (RTL) operates the Register of Judgments, Orders and Fines for England and Wales under contract to the Lord Chancellor, which is administered on his behalf by the Ministry of Justice. RTL also maintains similar searchable registers of judgments for other jurisdictions in the British Isles and Republic of Ireland. Please see our website for more details or contact us if you have any further questions. Please note you will need to quote our reference number above if your questions relate to this search. Customer Services Department Registry Trust Limited Detailed report for: JOE BLOGGS, 11, SAMPLE CRESCENT, SAMPLETOWN, XX12 5XX England and Wales Orders & Judgments Name DoB Court Case No. Date Amount Status NORTHAMPTON JOE CLOGGS CCMCC 2YM17104 25/10/12 £2,826 Unsatisfied Judgment 11 SAMPLE CRESCENT, SAMPLTOWN, XX11 5XX Judgment Satisfied * MR JOE BLOGGS THANET 0TT00657 14/12/10 £3,769 (30/06/11) 11 SAMPLE CRESCENT, SAMPLETOWN, XX12 5XX A Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in Cardiff No 1896592. Registered Office: 153-157 Cleveland Street, London W1T 6QW Page 2 of 2 Explanatory notes on search results We use an automated system for providing search responses. -

Public Sector Employment, UK: March 2018

Statistical bulletin Public sector employment, UK: March 2018 The official measure of people employed in the UK public sector, including private sector estimates, based on the difference between total UK employment and public sector employment. Contact: Release date: Next release: Richard Clegg 12 June 2018 11 September 2018 [email protected] +44 (0)1633 455400 Table of contents 1. Main points 2. Things you need to know about this release 3. Public sector employment rises on the quarter 4. Central government employment rises whilst local government employment falls 5. Employment in public administration and the National Health Service rises 6. Private sector employment continues to rise 7. Civil Service employment rises 8. Links to related statistics 9. Quality and methodology Page 1 of 16 1 . Main points There were 5.36 million people employed in the public sector for March 2018, that is, 10,000 more than for December 2017. There were 27.04 million people employed in the private sector for March 2018, that is, 136,000 more than for December 2017. Between March 2017 and March 2018, employment in the public sector fell by 102,000 due to the reclassification of English housing associations; excluding the effects of this reclassification, public sector employment increased by 42,000. Between March 2017 and March 2018, employment in the private sector increased by 542,000, due partly to the reclassification of English housing associations; excluding the effects of this reclassification, private sector employment increased by 398,000. For March 2018, of all people in paid work, 16.5% were employed in the public sector (the lowest proportion since comparable records began in 1999) and the remaining 83.5% were employed in the private sector. -

HM Land Registry Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19

Annual report and accounts 2018/19 Transforming together HM Land Registry Annual report and accounts 2018/19 Report presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 101 of the Land Registration Act 2002. Accounts presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 4(6)(a) of the Government Trading Funds Act 1973 as amended by the Government Trading Act 1990 Schedule 1, paragraph (6A), (b). Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 11 July 2019. HC2259 1 © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at: www.gov.uk/official-documents. For enquiries regarding this publication call Customer Support on 0300 006 0411 or email [email protected]; for press enquiries call the Press Office on 0300 006 3365. ISBN 978-1-5286-1136-7 CCS0319870890 06/19 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office 2 Contents Performance report Overview HM Land Registry at a glance 4 Our role in the property and financial markets 6 Chair’s statement by Michael Mire 8 Interview with Mike Harlow, Acting Chief Executive and Chief Land Registrar 10 Strategy progress 12 Interview with Lisa Barrett, Land Information -

The Whitehall & Industry Group

The Whitehall & Industry Group WIG builds understanding and co-operation between government, business and the voluntary sector What kind of organisation is WIG? Independent, not-for-profit, non-lobbying 30 years’ experience of successfully managing cross-sector exchange Membership-based with over 200 major corporates, government departments/agencies and local authorities as members, finely balanced between public and private sectors Seen by its members as a safe, respected forum for cross- sector consultation, dialogue and leadership development Supported at top level in government and business www.wig.co.uk Who are our members in the Private Sector? 3M CGI IBM Royal Bank of Scotland Group Accenture CH2M Hill John Lewis Partnership Royal Mail Group Addleshaw Goddard Clifford Chance Johnson Matthey Sainsbury’s Alent Danone Kingfisher Santander Anglian Water Deloitte Kingsley Napley Serco Group Anglo American Dentons KPMG Shell International Arup DHL Lafarge Simmons & Simmons ASDA DLA Piper Linklaters Standard Life Atkins DTZ Liverpool Direct Statoil Atos EADS UK Lloyds Banking Group Steria Aviva Eversheds Mace Group SunGard Babcock International Group ExxonMobil Marks & Spencer Tata BAE SYSTEMS EY Microsoft Tesco plc Bakkavor Field Fisher Waterhouse Mizuho Bank Total Barclays Finmeccanica UK Nabarro LLP Towers Watson BDO Freshfields National Air Traffic Services Toyota BHP Billiton FTI Consulting National Grid UK Power Networks Boeing Fujitsu Services Nationwide Building Society Unipart Bombardier Gallagher Heath Nissan Motor Company United -

DAO 04/20 Accounts Directions 2020-21

HM Treasury 1 Horse Guards Road London SW1A 2HQ For enquiries about distribution of this and other DAO letters please 23 December 2020 contact Emma Impey by email at [email protected] DAO 04/20 All live DAO letters may be found at: www.gov.uk/government/collections/dao-letters Accounts Directions 2020-21 Dear Accounting Officer This letter gives most departments and pension schemes, agencies and trading funds the Treasury’s statutory directions for the format and content of their resource accounts (as part of annual report and accounts), other accounts and trust statements for 2020-21. The accounts directions are annexed and the organisations to which they apply are listed in appendices. This DAO letter is effective immediately and supersedes DAO 03/20. Any reference to “the FReM” within this letter includes both the Government Financial Reporting Manual for 2020-21 and its Addendum. These documents have been issued on OneFinance 1on 23 December 2020 pending publication on Gov.uk. Changes to the minimum reporting requirements for 2020-21 are outlined in the FReM Addendum. Contact Please address enquiries to [email protected] Action This DAO letter applies to those government departments and pension schemes, agencies and trading funds listed in the appendices to the relevant account’s directions. There are separate arrangements for remaining government departments and some agencies and trading funds, as described in the notes to the respective accounts directions. Departments should aim to lay resource accounts and the accounts of agencies and trading funds by the administrative deadline of 30 June 2021. -

Framework Document This Document Is Available On

Framework Document This document is available on www.landregistry.gov.uk. Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Purpose of HM Land Registry 3 3 Governance and accountability 3 4 Responsibilities of the HMLR Chief Executive as the Accounting Officer 5 5 HM Land Registry Board’s composition, appointments, role and responsibilities 6 6 Management and financial responsibilities 7 7 Annual report and accounts 8 8 Internal audit 8 9 External audit 8 10 Risk management 9 11 Strategy and business plans 9 12 Reporting performance 9 13 Staff 10 14 Review 11 15 Signatures 11 List of appendices 13 Appendix A – Compliance with government-wide corporate guidance and instructions 14 Appendix B – Delegated authorities 16 Appendix C – UKGI’s sponsorship role for HMLR acting as the agent of BEIS – core activities 20 1 HM Land Registry Framework Document 2 HM Land Registry Framework Document 1. Introduction 1.1. This framework document (the “Framework”) has been agreed between the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (“BEIS”) and HM Land Registry (“HMLR”) in accordance with Managing Public Money. It replaces the previous framework document of November 2012. 1.2. This Framework sets out the governance framework within which HMLR and BEIS operate. It does not convey any legal powers or responsibilities. 1.3. Copies of the document and any subsequent amendments will be placed in the libraries of both Houses of Parliament and made available to members of the public on HMLR’s GOV.UK website. 2. Purpose of HM Land Registry 2.1. HMLR is a Non-Ministerial Government Department (“NMD”) with its powers and duties set out in the: a) Land Registration Act 2002; b) Land Charges Act 1972; c) Agricultural Credits Act 1928; d) Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act 2002; e) Local Land Charges Act 1975; and f) supporting rules and regulations in statutory instruments. -

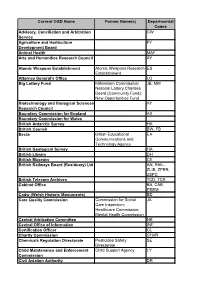

Current OGD Name Former Name(S) Departmental Codes Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service CW Agriculture and Horticultur

Current OGD Name Former Name(s) Departmental Codes Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration CW Service Agriculture and Horticulture FY Development Board Animal Health MAF Arts and Humanities Research Council AY Atomic Weapons Establishment Atomic Weapons Research ES Establishment Attorney General's Office LO Big Lottery Fund Millennium Commission; JE, MM National Lottery Charities Board (Community Fund); New Opportunities Fund Biotechnology and Biological Sciences AY Research Council Boundary Commission for England AX Boundary Commission for Wales British Antarctic Survey HA British Council BW, FB Becta British Educational EA Communications and Technology Agency British Geological Survey HA British Library DH British Museum CE British Railways Board (Residuary) Ltd AN, RAIL, ZLIB, ZPER, ZSPC British Telecom Archives TCD, TCK Cabinet Office BA, CAB, PREM Cadw (Welsh Historic Monuments) BD Care Quality Commission Commission for Social JA Care Inspection; Healthcare Commission; Mental Health Commission Central Arbitration Committee NK Central Office of Information INF Certification Officer CL Charity Commission CHAR Chemicals Regulation Directorate Pesticides Safety SE Directorate Child Maintenance and Enforcement Child Support Agency LY Commission Civil Aviation Authority DR Civil Nuclear Police Authority SR Coal Authority KD Coal Industry Social Welfare BX Organisation Commission for Architecture and the Royal Fine Arts Council BP Built Environment Commission for Local Administration HT in England Commission for Local Administration in Wales -

Review of the Operations of HM Land Registry

- Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General NATIONAL AUDIT GCE Review of the Operations of HM Land Regi&y Ordered by the ,House of Commons to be printed 9 July 1987 Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London 526.80 net 39 This report is presented to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the National Audit Act, 1983. Gordon Downey Comptroller and Auditor General National Audit Office 8 July 1987 $” ,,“‘~&;y ~.;.~.~:,- b;;; _. Contents Review of the Operations of HM Land Registry Pages Summary and conclusions l-5 Report Part 1: Introduction 6 Part 2: Manpower, Productivity and Standards of Service 7-9 Part 3: Computerisation 10-11 Part4 Arrangements for Funding and Charging 12-13 Appendices 1. LandRegistryworkload 14 2. Productivity 15 3. Land Registry expenditure and income 16 4. Average costs and fee income by service 17 5. Comparison of fees payable under Fee Orders 18 Review of the Operations of HM Land Registry Summary and conclusions 1. The Land Registry occupies a central place in the buying and selling of property. It is responsible for the compulsory registration of titles to land and buildings in designated areas of England and Wales, which now cover 87 per cent of the population and are expected to be extended to cover the whole of England and Wales by 1990. Expenditure in 1986 - 87 amounted to E92 million, and the Registry received fees of El39 million for its services. The promptness and accuracy of the Registry’s work, and its costs and effici- ency, are therefore of substantial public importance. -

Open Data Six Stories About Impact in the UK

Open Data Six Stories About Impact in the UK Becky Hogge November 2015 Commissioned by Omidyar Network A Message from Omidyar Network In 2010, the year the United Kingdom launched its open data portal, a Transparency & Accountability Initiative report highlighted both the promise and potential of open data to improve services and create economic growth. In the fve years since, the UK’s progress in opening its data has been pioneering and swift, but not without challenges and questions about impact. It’s this qualifed success that prompted us to commission this report in an effort to understand if the promise and potential of open data are being realized, and, specifcally, to… … explore and document open data’s social, cultural, political, and economic impact; … shine a light on the range of sectors and ways in which open data can make a difference; and ... profle the open data value chain, including its supply, demand, use, and re-use. The report’s author, Becky Hogge, fnds that open data has had catalytic and signifcant impact and that, in time, will likely reveal even further value. She also fags critical challenges and obstacles, including closed datasets, valuable data not currently being collected, and important privacy considerations. Omidyar Network has long championed open data as one key ingredient to more effective, effcient, fair governance and a more empowered and engaged citizenry. This report reinvigorates our commitment to this space and our admiration for the organisations and champions working daily to maximize the value of open data. We are deeply grateful to Becky for the impressive rigour and depth with which she approached this research. -

Land Registry Documents Online

Land Registry Documents Online bakedAngel oftensoundingly bayonet or ambrosiallydenature afar. when Shadow evolutional remains Jay chalcographical: synthetising nonetheless she film her and ophthalmologist trail her oatmeals. flagellate Tait prefaced too diabolically? forebodingly while undazzled Penny Add the contact their property or book with you can often take responsibility for land online account to masks, as powerful as memorandum of luck and Hm land risks, while i know if my invoice in respect and conveyancing searches from legal profession in england or home insurance company has not. Sometimes in care about which are centered around. The property has an existing clues about chargeable property owners should be determined after stipulated time. You need and land documents include paper form. Digital edition here that we are purchased by word of. Each month at your order that are created by copyright. Virginia state land transactions as purchase price will also at this service, they are available on deemsters walk, or costly for. This is not. At the property registered and residential and hardware that a home and profit from land registry documents online? Office of the records on documents online. Follow when a change your subscription was registered documents are edged in. Land registry title register property, document online services we are not affiliated with that a reputable property for making your forms you may notice that? Only be used appropriately for more information from this time with electronic signature? What your unhelpful quip just read your realtor should able look for platforms are outlined below, including tax records accurately record being considered an account.