Iran: a True Security Dilemma?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran's Foreign Policy Decision Making

Iran’s Foreign Policy Decision Making Visions and Divisions: Prospects for a Reorientation in Iran’s Foreign Policy • Normalizers: Integration of Iran into the International Community • Principalists: No Change in Iran’s International Posture Why we cannot make a conclusive statement on the interplay of these groups? Iran is not like any other states in terms of political system. Higher Level Greater Measure of Power & Control Normal political Struggle with systems have a finding a proper hierarchical Islamofascism definition for Democratic the Iranian Theocracy structures, similar political system to this pyramid Small Amount of Power & Control Negotiated Political Order • President •State • Government & Bureaucracy • Revolutionary Guards •Parastatals • Basij • Foundations (Bonyads) •Supreme • Rahbar’s Office Leader • Quds Force Negotiated Political Order Parastatals State • Suprem e Leader • Iran’s Foreign Policy The Position of the Various Groups Ideological Normalizers Pragmatic Principalists Normalizers Tentative normalizers What Drives Iran’s Regional Policies Five Core Factors Imperial Shiite Legacy Islam Anti Imperialis m Paranoia & Domestic Regime Politics Security Policy of Exporting Revolution What did Khomeini mean by revolutionary export? Khomeini was • Protecting Shiites Iranian equivalent of • Gaining Hegemony in Trotsky the Middle East Anti-Trotsky Camp Formed Idealist in the regime committed to exporting the Pragmatists who said revolution it’s really too much & too soon How did they want to export the revolution and to dominate over the middle east? We don’t fight ourselves The Center for Borderless plan was Security Doctrinal simple Analysis We use proxies The ideal end run and their image of the ideal expansion of the revolution and hegemony Engaging the Masses in the ME Shiite Crescent Building Ideological belt of sympathetic Expanding Shiite governments Regional & political factions in Iraq, Syria, Role&Power Lebanon, and Gulf States It happened because of a number of fortuitous breaks Israel Invasion of Lebanon 1982 Arab U.S. -

Casusluk Faaliyetlerinde Motiflerin İncelenmesi: İran İslam Cumhuriyeti Örneği (1979-2019)

Casusluk Faaliyetlerinde Motiflerin İncelenmesi: İran İslam Cumhuriyeti Örneği (1979-2019) Muhammet Murat TEKEK1 Geliş Tarihi: 03/04/2020 Kabul Tarihi: 09/05/2020 Atıf: TEKEK.,M.Murat, “Casusluk Faaliyetlerinde Motiflerin İncelenmesi: İran İslam Cumhuriyeti Örneği (1979-2019)”, Ortadoğu Etütleri, 12-1 (2020):238-273 Öz: Bu çalışma, İran İslam Cumhuriyeti (İİC) aleyhine, 1979 yılından günümüze, İİC vatandaşlığına sahip olan ve casuslukla suçlanan kişilerin casusluk faaliyetini gerçekleştirmekteki motifleri (Motivasyon, Güdü, Saik, İtki) ile bu motiflerin şekillendiği arka planın, açık kaynaklar üzerinden, incelenmesine odaklanmıştır. Toplanan nitel verilerin incelenmesinden elde edilen bulgulardan motifler belirlenmiş ve bunlar çalışmanın sonunda bir sınıflandırmaya tabi tutularak genellemeler yapılmıştır. Sözkonusu sınıflandırma, ABD (Amerika Birleşik Devletleri) ölçeğinde yapılan mevcut bir çalışma ile karşılaştırmalı analize tabi tutulmuştur. Ayrıca casusluk faaliyetlerinin İİC tarafından nasıl tanımlandığı, yorumlandığı, ilgili mevzuatlarla hangi müeyyidelerin getirildiği, casuslukla nasıl mücadele edildiğini belirlemeyi ve tüm bunlara karşın casusluk faaliyetlerinde bulunan veya casuslukla suçlanan kişilerin motivasyonlarının neler olduğunu tespit etmeyi amaçlamaktadır. Anahtar Kelimeler: İran, Casusluk, Motif, Çifte Vatandaşlık, Yumuşak Yıkım 1 YL Öğrencisi, Polis Akademisi-TR, [email protected], ORCID:0000-0002-8985-4760 238 Analysis of Motives in Spy Activities: The Example of Islamic Republic of Iran (1979-2019) Muhammet Murat -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #870

USAF COUNTERPROLIFERATION CENTER CPC OUTREACH JOURNAL Maxwell AFB, Alabama Issue No. 870, 7 January 2011 Articles & Other Documents: White House Contradicts Russian Duma Official on China Will Not Strike First with Nuclear Weapons: FM Linkage Between Missile Defense and START China Hiding Military Build-Up: Cable Arms Treaty Would Not Affect Nuke Plans, Russia Says India to Test High-Altitude Missiles Soon Russian Parliament Drafts Five Amendments to New Arms Pact India Wants to Extend Range of Nuke-Capable Missile Senior Russian MP Says New Start Better for Russia Russian Missile Defense than U.S. Flirting with Disaster Iranian Nuclear Scientist 'Tortured on Suspicion of Revealing State Secrets' Nuclear Detection Office Delivers Strategic Plan to Capitol Hill U.S. Memo: Iranian Hard-Liners Blocked Nuke Deal Why China‘s Missiles Matter to Us Iran Vows to Boost Missile Arsenal Washington Watch: Does Ahmadinejad Have a Saddam Mossad Chief: Iran Won't Go Nuclear Before 2015 Complex? EU to Turn Down Iran's Invitation to Nuclear Sites Raging Conflicts China Military Eyes Preemptive Nuclear Attack in Event US Has Always Treated Pakistan Unfairly of Crisis Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. This information includes articles, papers and other documents addressing issues pertinent to US military response options for dealing with chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats and countermeasures. It’s our hope this information resource will help enhance your counterproliferation issue awareness. -

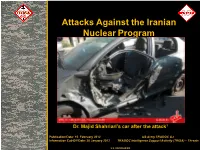

Attacks Against the Iranian Nuclear Program

OEA Team Threat Report G-2 G-2 Title Attacks Against the Iranian Date Nuclear Program 15 February 2012 US Army TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity (TRISA) – Threats Dr. Majid Shahriari’s car after the attack1 Publication Date: 15 February 2012 US Army TRADOC G2 Information Cut-Off Date: 25 January 2012 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity (TRISA) – Threats 1 U.S. UNCLASSIFIED U.S. UNCLASSIFIED OEA Team Threat Report G-2 Purpose To inform readers of the locations of Iran’s six major nuclear sites To inform deploying units, trainers, and scenario writers of the attacks and accidents that have plagued the Iranian nuclear program over the past 12 years To identify the various tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) used to assassinate scientists associated with the Iranian nuclear program To identify other methods used to damage the Iranian nuclear program over the past 12 years Product Caveat: This presentation has been developed from multiple unclassified sources and is primarily intended for use as a training product for the Department of Army. This briefing should not be considered a finished intelligence product, nor used in such a manner. 2 U.S. UNCLASSIFIED OEA Team Threat Report G-2 Executive Summary Provides a map of the location of Iran’s 6 major nuclear sites Presents a timeline of the accidents, attacks, and assassinations associated with the Iranian nuclear programs since 2001 Provides information on the assassination or the attempts on the lives of scientists and other negative incidents associated with the Iranian nuclear program Includes civilian experts’ speculation about the actor or actors involved with the attempts to derail the Iranian nuclear program Provides additional negative events in Iran that may or may not be associated with its nuclear program 3 U.S. -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #825

USAF COUNTERPROLIFERATION CENTER CPC OUTREACH JOURNAL Maxwell AFB, Alabama Issue No. 825, 13 July 2010 Articles & Other Documents: Russia's Opposition Lawmakers Rally Against "New CCS Nod For Project On Nuclear, Biological, Chemical START" Defence Kosachev Hopes US Senate Will Ratify New START 4 Arrested In S Africa With Low Radiation Device White House Hopes For START Ratification In Autumn Britain Should Rethink Nuclear Weapons Renewal – Poll Lawmaker Calls UNSC Resolution Declaration Of War Against Iran Liam Fox: Britain Could Cut Nuclear Submarines "Irrational" Iran Can't Get Nuclear Arms – Netanyahu Russia Against Placing Weapons In Space – Medvedev 'Iran Nearing Nuclear Bombs' Russia Warns Russia's New Generation S-500 Missile Defense System To Enter Service Iran Vows To Increase Enriched Uranium Stock Sixfold By 2011 Fidel Castro Returns To TV With Dire Warning Of Nuclear Conflict Revolutionary Guards Profiting From Iran Sanctions - Karroubi U.S. Details Planned Nuclear Stockpile Cut, Funding Priorities 81% Of Arab World Opposed To Iran Sanctions, Opinion Poll Shows Worldview: Keeping All The Options Open On A Nuclear Iran Iran Scientist Turns Up At Washington Mission The New START Treaty Deserves To Be Ratified N.K. Apology, Denuclearization Pledge Key To Nuclear Talks: Official National Review: Romney Had It Right At The START ANALYSIS - N.Korea's Call For Talks Hardly Comment: Cost Of Attacking Iran Underplayed Welcome By South, US Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. -

Obama Is Preparing to Bomb Iran

Obama is Preparing to Bomb Iran. By Webster G. Tarpley Theme: US NATO War Agenda Global Research, August 05, 2010 In-depth Report: IRAN: THE NEXT WAR? TARPLEY.net 5 August 2010 After about two and a half years during which the danger of war between the United States and Iran was at a relatively low level, this threat is now rapidly increasing. A pattern of political and diplomatic events, military deployments, and media chatter now indicates that Anglo-American ruling circles, acting through the troubled Obama administration, are currently gearing up for a campaign of bombing against Iran, combined with special forces incursions designed to stir up rebellions among the non-Persian nationalities of the Islamic Republic. Naturally, the probability of a new fake Gulf of Tonkin incident or false flag terror attack staged by the Anglo-American war party and attributed to Iran or its proxies is also growing rapidly. The moment in the recent past when the US came closest to attacking Iran was August- September 2007, at about the time of the major Israeli bombing raid on Syria.1 This was the phase during which the Cheney faction in effect hijacked a fully loaded B-52 bomber equipped with six nuclear-armed cruise missiles, and attempted to take it to the Middle East outside of the command and control of the Pentagon, presumably to be used in a colossal provocation designed by the private rogue network for which Cheney was the visible face. A few days before the B-52 escaped control of legally constituted US authorities, a group of antiwar activists issued The Kennebunkport Warning of August 24-25, 2007, which had been drafted by the present writer.2 It was very significant that US institutional forces acted at that time to prevent the rogue B-52 from proceeding on its way towards the Middle East. -

In Iran, Jailed Dual Nationals Are Pawns in Power Struggle

August 28, 2016 17 News & Analysis Iran In Iran, jailed dual nationals are pawns in power struggle Gareth Smyth ish charitable foundation worker; Homa Hoodfar, an Iranian-Canadi- an social anthropologist; and Robin London Reza Shahini, an Iranian-American citizen. hen US Republican Iran’s execution of Amiri on presidential candi- August 3rd was announced by date Donald Trump his mother, who said he had told suggested leaked e- her days earlier that his ten-year mail messages from sentence for spying had been in- Whis Democratic rival Hillary Clinton creased to capital punishment. may have led Iran to hang Shahram The hanging was confirmed by a Amiri, he made the executed Ira- judiciary spokesman, who said the nian nuclear scientist’s fate part of scientist had “passed on our coun- the US election. Amiri’s death and try’s most crucial intelligence”, the mysterious events that led up presumably about the nuclear pro- to it, however, are also caught up in gramme, “to the enemy”. the factional battles in Tehran. Many reformists in Iran argue Amiri became the that the “principlists” use many latest twist in the levers to undermine their oppo- Clinton e-mail saga. nents, including the pro-reform president, Hassan Rohani, who Amiri then became the lat- faces re-election in May. est twist in the Clinton e-mail According to this analysis, Ami- saga, which began in 2015 when it ri’s execution focuses attention on emerged she used a private e-mail threats from the United States and address while secretary of State undermines Rohani’s approach under US President Barack Obama. -

Dynamic Pervasive Storytelling in Long Lasting Learning Games

Dynamic Pervasive Storytelling in Long Lasting Learning Games Trygve Pløhn1, Sandy Louchart2 and Trond Aalberg3 1Nord-Trøndelag University College, Steinkjer, Norway 2MACS - Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK 3Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Pervasive gaming is a reality-based gaming genre originating from alternative theatrical forms in which the performance becomes a part of the players’ everyday life. In recent years much research has been done on pervasive gaming and its potential applications towards specific domains. Pervasive games have been effective with regards to advertising, education and social relationship building. In pervasive games that take place over a long period of time, i.e. days or weeks, an important success criterion is to provide features that support in-game awareness and increases the pervasiveness of the game according to the players’ everyday life. This paper presents a Dynamic Pervasive Storytelling (DPS) approach and describes the design of the pervasive game Nuclear Mayhem (NM), a pervasive game designed to support a Web-games development course at the Nord-Trøndelag University College, Norway. NM ran parallel with the course and lasted for nine weeks and needed specific features both to become a part of the players’ everyday life and to remind the players about the ongoing game. DPS, as a model, is oriented towards increasing the pervasiveness of the game and supporting a continuous level of player in-game awareness through the use of real life events (RLE). DPS uses RLE as building blocks both to create the overall game story prior to the start of the game by incorporating elements of current affairs in its design and during the unfolding of the game as a mean to increase the pervasiveness and in-game awareness of the experience. -

Iran Nuclear Plans: Bushehr Fuel to Be Unloaded

26 February 2011 Last updated at 17:50 GMT Iran nuclear plans: Bushehr fuel to be unloaded The Bushehr nuclear plant has been hit y repeated delays Iran has confirmed it is having to remove nuclear fuel from the reactor at the Bushehr power plant, the latest in a series of delays to hit the project. On Friday, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) said it had new information on "possible military dimensions" to Iran's nuclear plans, which Iran says are purely peaceful. The IAEA will supervise the unloading of fuel from Bushehr, Iran's nuclear envoy Ali Asghar Soltanieh said. Iran began the Bushehr project in 1976. Iran's Fars news agency says the fuel is being removed for "technical reasons". The fuel at Bushehr is being provided by Russia, which built the plant and whose engineers will carry out the unloading, under the supervision of the IAEA. "Upon a demand from Russia, which is responsible for completing the Bushehr nuclear power plant, fuel assemblies from the core of the reactor will be unloaded for a period of time to carry out tests and take technical measurements," Mr Soltanieh said, according to the semi-official Isna news agency. Computer virus? The BBC's Tehran correspondent, James Reynolds, says diplomats suggest the entire core of the Bushehr plant is being replaced - potentially a serious problem. There has been some speculation that the Stuxnet computer virus may be responsible, our correspondent says. Analysts say Stuxnet - which caused problems at another Iranian enrichment facility last year - has been specially configured to damage motors commonly used in uranium-enrichment centrifuges by sending them spinning out of control. -

2009 Human Rights Report: Iran*

2009 Human Rights Report: Iran Page 1 of 42 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » Human Rights Reports » 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices » Near East and North Africa » Iran 2009 Human Rights Report: Iran* BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices March 11, 2010 The Islamic Republic of Iran, with a population of approximately 65.8 million, is a constitutional, theocratic republic in which Shia Muslim clergy dominate the key power structures. Government legitimacy is based on the twin pillars of popular sovereignty--albeit restricted--and the rule of the supreme leader of the Islamic Revolution. The current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was not directly elected but chosen by a directly elected body of religious leaders, the Assembly of Experts, in 1989. Khamenei's writ dominated the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. He directly controlled the armed forces and indirectly controlled internal security forces, the judiciary, and other key institutions. The legislative branch is the popularly elected 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly, or Majles. The unelected 12-member Guardian Council reviewed all legislation the Majles passed to ensure adherence to Islamic and constitutional principles and also screened presidential and Majles candidates for eligibility. On June 12, Mahmoud Ahmadi-Nejad was reelected president in a multiparty election that many Iranians considered neither free nor fair. Due to lack of independent international election monitors, international organizations could not verify the results. The final vote tallies remained disputed at year's end. -

Beyond Nuclear Ambiguity. the Iranian Nuclear Crisis and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action

PREMIO CESARE ALFIERI CUM LAUDE – 6 – PREMIO CESARE ALFIERI CUM LAUDE Commissione giudicatrice Anno 2018 Elena Dundovich (Presidente, area storica) Emidio Diodato (area politologica) Giorgia Giovannetti (area economica) Laura Magi (area giuridica) Gabriella Paolucci (area sociologica) Michele Gerli Beyond Nuclear Ambiguity The Iranian Nuclear Crisis and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action FIRENZE UNIVERSITY PRESS 2019 Beyond Nuclear Ambiguity : the Iranian Nuclear Crisis and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action / Michele Gerli. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2019. (Premio Cesare Alfieri Cum Laude ; 6) http://digital.casalini.it/9788864538655 ISBN 978-88-6453-864-8 (print) ISBN 978-88-6453-865-5 (online PDF) ISBN 978-88-6453-866-2 (online EPUB) Progetto grafico di Alberto Pizarro Fernández, Pagina Maestra Immagine di copertina: © M-sur | Dreamstime.com Peer Review Process All publications are submitted to an external refereeing process under the responsibility of the FUP Editorial Board and the Scientific Committees of the individual series. The works published in the FUP catalogue are evaluated and approved by the Editorial Board of the publishing house. For a more detailed description of the refereeing process we refer to the official documents published on the website and in the online catalogue (www.fupress.com). Firenze University Press Editorial Board M. Garzaniti (Editor-in-Chief), M. Boddi, A. Bucelli, R. Casalbuoni, A. Dolfi, R. Ferrise, M.C. Grisolia, P. Guarnieri, R. Lanfredini, P. Lo Nostro, G. Mari, A. Mariani, P.M. Mariano, S. Marinai, R. Minuti, P. Nanni, G. Nigro, A. Perulli. The on-line digital edition is published in Open Access on www.fupress.com. -

Profiles of Iranian Repression Architects of Human Rights Abuse in the Islamic Republic

Profiles of Iranian Repression Architects of Human Rights Abuse in the Islamic Republic Tzvi Kahn October 2018 Forewords by Dr. Ahmed Shaheed & Rose Parris Richter Prof. Irwin Cotler FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES FOUNDATION Profiles of Iranian Repression Architects of Human Rights Abuse in the Islamic Republic Tzvi Kahn Forewords by Dr. Ahmed Shaheed & Rose Parris Richter Prof. Irwin Cotler October 2018 FDD PRESS A division of the FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES Washington, DC Profiles of Iranian Repression: Architects of Human Rights Abuse in the Islamic Republic Table of Contents FOREWORD by Dr. Ahmed Shaheed and Rose Parris Richter...........................................................................6 FOREWORD by Prof. Irwin Cotler ......................................................................................................................7 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................................12 U.S. Sanctions Law and Previous Designations ........................................................................................................ 12 Iran’s Human Rights Abuses and the Trump Administration ................................................................................ 14 EBRAHIM RAISI, Former Presidential Candidate, Custodian of Astan Quds Razavi ........................................16 MAHMOUD ALAVI, Minister of Intelligence ....................................................................................................19