U.S. Relationships with Iran, Israel, and Pakistan: a Realist Explanation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case #2 United States of America (Respondent)

Model International Court of Justice (MICJ) Case #2 United States of America (Respondent) Relocation of the United States Embassy to Jerusalem (Palestine v. United States of America) Arkansas Model United Nations (AMUN) November 20-21, 2020 Teeter 1 Historical Context For years, there has been a consistent struggle between the State of Israel and the State of Palestine led by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In 2018, United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the U.S. embassy located in Tel Aviv would be moving to the city of Jerusalem.1 Palestine, angered by the embassy moving, filed a case with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2018.2 The history of this case, U.S. relations with Israel and Palestine, current events, and why the ICJ should side with the United States will be covered in this research paper. Israel and Palestine have an interesting relationship between war and competition. In 1948, Israel captured the west side of Jerusalem, and the Palestinians captured the east side during the Arab-Israeli War. Israel declared its independence on May 14, 1948. In 1949, the Lausanne Conference took place, and the UN came to the decision for “corpus separatum” which split Jerusalem into a Jewish zone and an Arab zone.3 At this time, the State of Israel decided that Jerusalem was its “eternal capital.”4 “Corpus separatum,” is a Latin term meaning “a city or region which is given a special legal and political status different from its environment, but which falls short of being sovereign, or an independent city-state.”5 1 Office of the President, 82 Recognizing Jerusalem as the Capital of the State of Israel and Relocating the United States Embassy to Israel to Jerusalem § (2017). -

Iran's Foreign Policy Decision Making

Iran’s Foreign Policy Decision Making Visions and Divisions: Prospects for a Reorientation in Iran’s Foreign Policy • Normalizers: Integration of Iran into the International Community • Principalists: No Change in Iran’s International Posture Why we cannot make a conclusive statement on the interplay of these groups? Iran is not like any other states in terms of political system. Higher Level Greater Measure of Power & Control Normal political Struggle with systems have a finding a proper hierarchical Islamofascism definition for Democratic the Iranian Theocracy structures, similar political system to this pyramid Small Amount of Power & Control Negotiated Political Order • President •State • Government & Bureaucracy • Revolutionary Guards •Parastatals • Basij • Foundations (Bonyads) •Supreme • Rahbar’s Office Leader • Quds Force Negotiated Political Order Parastatals State • Suprem e Leader • Iran’s Foreign Policy The Position of the Various Groups Ideological Normalizers Pragmatic Principalists Normalizers Tentative normalizers What Drives Iran’s Regional Policies Five Core Factors Imperial Shiite Legacy Islam Anti Imperialis m Paranoia & Domestic Regime Politics Security Policy of Exporting Revolution What did Khomeini mean by revolutionary export? Khomeini was • Protecting Shiites Iranian equivalent of • Gaining Hegemony in Trotsky the Middle East Anti-Trotsky Camp Formed Idealist in the regime committed to exporting the Pragmatists who said revolution it’s really too much & too soon How did they want to export the revolution and to dominate over the middle east? We don’t fight ourselves The Center for Borderless plan was Security Doctrinal simple Analysis We use proxies The ideal end run and their image of the ideal expansion of the revolution and hegemony Engaging the Masses in the ME Shiite Crescent Building Ideological belt of sympathetic Expanding Shiite governments Regional & political factions in Iraq, Syria, Role&Power Lebanon, and Gulf States It happened because of a number of fortuitous breaks Israel Invasion of Lebanon 1982 Arab U.S. -

Iran: a True Security Dilemma?

1 Iran: A True Security Dilemma? The thesis of this paper is that there is a substantial basis to believe the acquisition of nuclear weapons by the Islamic Republic of Iran need not derail U.S. efforts to obtain its basic security objectives in the Middle East (e.g. the prevention of terrorism, secure corridors for the transportation of oil to global markets and progress on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict). There is no known evidence of a state giving a nuclear capability to a nonstate actor to support its national security. The paper notes that U.S. intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan precipitated Iranian reactions, including development of a nuclear weapons program, which pose challenges for international security. These developments enhance the strength of the Iranian regime against certain threats like the use of conventional military power. Using theories developed by proponents of the school of realism in international relations policy, the paper proceeds to show that the U.S. can still pursue its basic security goals in the region successfully. While nuclear weapons threatening U.S. interests are daunting, counter measures against them and steps to prevent proliferation are not certain to succeed. Parties involved in a conflict normally do not abandon working to secure their interests in tactical or low level actions simply because they face opposition (i.e.Taliban has continued its insurgency in Afghanistan despite U.S. state building efforts.). Accordingly, the U.S. needs to pursue balanced policy objectives in a disciplined manner while trying to mitigate the perceived risks from nuclear proliferation. This more balanced approach should be taken with Islamic Republic of Iran. -

Casusluk Faaliyetlerinde Motiflerin İncelenmesi: İran İslam Cumhuriyeti Örneği (1979-2019)

Casusluk Faaliyetlerinde Motiflerin İncelenmesi: İran İslam Cumhuriyeti Örneği (1979-2019) Muhammet Murat TEKEK1 Geliş Tarihi: 03/04/2020 Kabul Tarihi: 09/05/2020 Atıf: TEKEK.,M.Murat, “Casusluk Faaliyetlerinde Motiflerin İncelenmesi: İran İslam Cumhuriyeti Örneği (1979-2019)”, Ortadoğu Etütleri, 12-1 (2020):238-273 Öz: Bu çalışma, İran İslam Cumhuriyeti (İİC) aleyhine, 1979 yılından günümüze, İİC vatandaşlığına sahip olan ve casuslukla suçlanan kişilerin casusluk faaliyetini gerçekleştirmekteki motifleri (Motivasyon, Güdü, Saik, İtki) ile bu motiflerin şekillendiği arka planın, açık kaynaklar üzerinden, incelenmesine odaklanmıştır. Toplanan nitel verilerin incelenmesinden elde edilen bulgulardan motifler belirlenmiş ve bunlar çalışmanın sonunda bir sınıflandırmaya tabi tutularak genellemeler yapılmıştır. Sözkonusu sınıflandırma, ABD (Amerika Birleşik Devletleri) ölçeğinde yapılan mevcut bir çalışma ile karşılaştırmalı analize tabi tutulmuştur. Ayrıca casusluk faaliyetlerinin İİC tarafından nasıl tanımlandığı, yorumlandığı, ilgili mevzuatlarla hangi müeyyidelerin getirildiği, casuslukla nasıl mücadele edildiğini belirlemeyi ve tüm bunlara karşın casusluk faaliyetlerinde bulunan veya casuslukla suçlanan kişilerin motivasyonlarının neler olduğunu tespit etmeyi amaçlamaktadır. Anahtar Kelimeler: İran, Casusluk, Motif, Çifte Vatandaşlık, Yumuşak Yıkım 1 YL Öğrencisi, Polis Akademisi-TR, [email protected], ORCID:0000-0002-8985-4760 238 Analysis of Motives in Spy Activities: The Example of Islamic Republic of Iran (1979-2019) Muhammet Murat -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #870

USAF COUNTERPROLIFERATION CENTER CPC OUTREACH JOURNAL Maxwell AFB, Alabama Issue No. 870, 7 January 2011 Articles & Other Documents: White House Contradicts Russian Duma Official on China Will Not Strike First with Nuclear Weapons: FM Linkage Between Missile Defense and START China Hiding Military Build-Up: Cable Arms Treaty Would Not Affect Nuke Plans, Russia Says India to Test High-Altitude Missiles Soon Russian Parliament Drafts Five Amendments to New Arms Pact India Wants to Extend Range of Nuke-Capable Missile Senior Russian MP Says New Start Better for Russia Russian Missile Defense than U.S. Flirting with Disaster Iranian Nuclear Scientist 'Tortured on Suspicion of Revealing State Secrets' Nuclear Detection Office Delivers Strategic Plan to Capitol Hill U.S. Memo: Iranian Hard-Liners Blocked Nuke Deal Why China‘s Missiles Matter to Us Iran Vows to Boost Missile Arsenal Washington Watch: Does Ahmadinejad Have a Saddam Mossad Chief: Iran Won't Go Nuclear Before 2015 Complex? EU to Turn Down Iran's Invitation to Nuclear Sites Raging Conflicts China Military Eyes Preemptive Nuclear Attack in Event US Has Always Treated Pakistan Unfairly of Crisis Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. This information includes articles, papers and other documents addressing issues pertinent to US military response options for dealing with chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) threats and countermeasures. It’s our hope this information resource will help enhance your counterproliferation issue awareness. -

U.S. Air and Ground Conventional Forces for NATO: Mobility and Logistics Issues

BACKGROUND PAPER U.S. Air and Ground Conventional Forces for NATO: Mobility and Logistics Issues March 1978 Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office Washington, D.C. U.S. AIR AND GROUND CONVENTIONAL FORCES FOR NATO: MOBILITY AND LOGISTICS ISSUES The Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Qovernment Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 FT II PREFACE The defense budget that the Congress will be considering in fiscal year 1979 places a strong emphasis on improving U.S. conventional forces for NATO. U.S. decisions concerning air and ground conventional forces for NATO are, however, tied closely to, and must be assessed in terms of, the capabilities of our NATO allies. This paper outlines the increasing importance of mobility and logistics in NATO defense. It compares U.S. and allied capabilities in those areas and presents options regarding U.S. decisions on logistics and mobility. The paper is part of a CBO series on the U.S. military role in NATO. Other papers in this series are U.S. Air and Ground Conventional Forces for NATO: Overview (January 1978),Assessing the NATO/Warsaw Pact Military Balance"" (December 1977), and two forthcoming, background papers, Air Defense Issues and Firepower Issues. This series was under- taken at the request of the Senate Budget Committee. In accord- ance with CBO's mandate to provide objective analysis, the study offers no recommendations. This paper was prepared by Peggy L. Weeks and Alice C. Maroni of the National Security and International Affairs Division of the Congressional Budget Office, under the supervision of John E. -

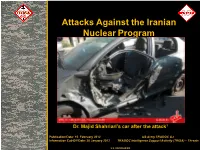

Attacks Against the Iranian Nuclear Program

OEA Team Threat Report G-2 G-2 Title Attacks Against the Iranian Date Nuclear Program 15 February 2012 US Army TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity (TRISA) – Threats Dr. Majid Shahriari’s car after the attack1 Publication Date: 15 February 2012 US Army TRADOC G2 Information Cut-Off Date: 25 January 2012 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity (TRISA) – Threats 1 U.S. UNCLASSIFIED U.S. UNCLASSIFIED OEA Team Threat Report G-2 Purpose To inform readers of the locations of Iran’s six major nuclear sites To inform deploying units, trainers, and scenario writers of the attacks and accidents that have plagued the Iranian nuclear program over the past 12 years To identify the various tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) used to assassinate scientists associated with the Iranian nuclear program To identify other methods used to damage the Iranian nuclear program over the past 12 years Product Caveat: This presentation has been developed from multiple unclassified sources and is primarily intended for use as a training product for the Department of Army. This briefing should not be considered a finished intelligence product, nor used in such a manner. 2 U.S. UNCLASSIFIED OEA Team Threat Report G-2 Executive Summary Provides a map of the location of Iran’s 6 major nuclear sites Presents a timeline of the accidents, attacks, and assassinations associated with the Iranian nuclear programs since 2001 Provides information on the assassination or the attempts on the lives of scientists and other negative incidents associated with the Iranian nuclear program Includes civilian experts’ speculation about the actor or actors involved with the attempts to derail the Iranian nuclear program Provides additional negative events in Iran that may or may not be associated with its nuclear program 3 U.S. -

ATLAS SUPPORTED: Strengthening U.S.-Israel Strategic Cooperation

ATLAS SUPPORTED: Strengthening U.S.-Israel Strategic Cooperation JINSA’s Gemunder Center U.S.-Israel Security Task Force Chairman Admiral James Stavridis, USN (ret.) May 2018 DISCLAIMER The findings and recommendations contained in this publication are solely those of the authors. Task Force and Staff Chairman Admiral James Stavridis, USN (ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander and former Commander of U.S. European Command Members General Charles Wald, USAF (ret.) Former Deputy Commander of U.S. European Command LTG John Gardner, USA (ret.) Former Deputy Commander of U.S. European Command Lt Gen Henry Obering, USAF (ret.) Former Director of U.S. Missile Defense Agency JINSA Gemunder Center Staff Michael Makovsky, PhD President & CEO Harry Hoshovsky Policy Analyst Jonathan Ruhe Associate Director Table of Contents Executive Summary 7 Strategic Overview 17 Growing Iranian threat to the Middle East 18 Israel’s vital role in defending mutual interests 19 New opportunities for U.S.-led regional defense 20 Recommendations 21 Elevate Israel’s official standing as an ally to that of Australia 21 Frontload the MoU to ensure Israel’s qualitative military edge (QME) 26 Replenish and regionalize prepositioned munitions stockpiles in Israel 28 Drive Israeli-Arab regional security cooperation 29 Support Israel’s legitimate security needs against the Iranian threat in Syria 33 Develop new frontiers for bilateral military cooperation and R&D 35 Endnotes 37 I. Executive Summary “Beautiful,” is how Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu recently described the relationship between the United States and Israel, two liberal democratic countries which acutely share many values and security interests. The United States recognized the State of Israel minutes after the Jewish state was established 70 years ago this month, but a bilateral strategic partnership only began several decades later during the height of the Cold War. -

Strengthening US-Israel Strategic Cooperation

ATLAS SUPPORTED: Strengthening U.S.-Israel Strategic Cooperation JINSA’s Gemunder Center U.S.-Israel Security Task Force Chairman Admiral James Stavridis, USN (ret.) May 2018 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of JINSA’s Gemunder Center U.S.-Israel Security Task Force. The findings expressed herein are those solely of the Task Force. The report does not necessarily represent the views or opinions of JINSA, its founders or its board of directors. Task Force and Staff Chairman Admiral James Stavridis, USN (ret.) Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander and former Commander of U.S. European Command Members General Charles Wald, USAF (ret.) Former Deputy Commander of U.S. European Command LTG John Gardner, USA (ret.) Former Deputy Commander of U.S. European Command Lt Gen Henry Obering, USAF (ret.) Former Director of U.S. Missile Defense Agency JINSA Gemunder Center Staff Michael Makovsky, PhD President & CEO Harry Hoshovsky Policy Analyst Jonathan Ruhe Associate Director Table of Contents Executive Summary 7 Strategic Overview 17 Growing Iranian threat to the Middle East 18 Israel’s vital role in defending mutual interests 19 New opportunities for U.S.-led regional defense 20 Recommendations 21 Elevate Israel’s official standing as an ally to that of Australia 21 Frontload the MoU to ensure Israel’s qualitative military edge (QME) 26 Replenish and regionalize prepositioned munitions stockpiles in Israel 28 Drive Israeli-Arab regional security cooperation 29 Support Israel’s legitimate security needs against the Iranian threat in Syria 33 Develop new frontiers for bilateral military cooperation and R&D 35 Endnotes 37 I. Executive Summary “Beautiful,” is how Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu recently described the relationship between the United States and Israel, two liberal democratic countries which acutely share many values and security interests. -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #825

USAF COUNTERPROLIFERATION CENTER CPC OUTREACH JOURNAL Maxwell AFB, Alabama Issue No. 825, 13 July 2010 Articles & Other Documents: Russia's Opposition Lawmakers Rally Against "New CCS Nod For Project On Nuclear, Biological, Chemical START" Defence Kosachev Hopes US Senate Will Ratify New START 4 Arrested In S Africa With Low Radiation Device White House Hopes For START Ratification In Autumn Britain Should Rethink Nuclear Weapons Renewal – Poll Lawmaker Calls UNSC Resolution Declaration Of War Against Iran Liam Fox: Britain Could Cut Nuclear Submarines "Irrational" Iran Can't Get Nuclear Arms – Netanyahu Russia Against Placing Weapons In Space – Medvedev 'Iran Nearing Nuclear Bombs' Russia Warns Russia's New Generation S-500 Missile Defense System To Enter Service Iran Vows To Increase Enriched Uranium Stock Sixfold By 2011 Fidel Castro Returns To TV With Dire Warning Of Nuclear Conflict Revolutionary Guards Profiting From Iran Sanctions - Karroubi U.S. Details Planned Nuclear Stockpile Cut, Funding Priorities 81% Of Arab World Opposed To Iran Sanctions, Opinion Poll Shows Worldview: Keeping All The Options Open On A Nuclear Iran Iran Scientist Turns Up At Washington Mission The New START Treaty Deserves To Be Ratified N.K. Apology, Denuclearization Pledge Key To Nuclear Talks: Official National Review: Romney Had It Right At The START ANALYSIS - N.Korea's Call For Talks Hardly Comment: Cost Of Attacking Iran Underplayed Welcome By South, US Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. -

Obama Is Preparing to Bomb Iran

Obama is Preparing to Bomb Iran. By Webster G. Tarpley Theme: US NATO War Agenda Global Research, August 05, 2010 In-depth Report: IRAN: THE NEXT WAR? TARPLEY.net 5 August 2010 After about two and a half years during which the danger of war between the United States and Iran was at a relatively low level, this threat is now rapidly increasing. A pattern of political and diplomatic events, military deployments, and media chatter now indicates that Anglo-American ruling circles, acting through the troubled Obama administration, are currently gearing up for a campaign of bombing against Iran, combined with special forces incursions designed to stir up rebellions among the non-Persian nationalities of the Islamic Republic. Naturally, the probability of a new fake Gulf of Tonkin incident or false flag terror attack staged by the Anglo-American war party and attributed to Iran or its proxies is also growing rapidly. The moment in the recent past when the US came closest to attacking Iran was August- September 2007, at about the time of the major Israeli bombing raid on Syria.1 This was the phase during which the Cheney faction in effect hijacked a fully loaded B-52 bomber equipped with six nuclear-armed cruise missiles, and attempted to take it to the Middle East outside of the command and control of the Pentagon, presumably to be used in a colossal provocation designed by the private rogue network for which Cheney was the visible face. A few days before the B-52 escaped control of legally constituted US authorities, a group of antiwar activists issued The Kennebunkport Warning of August 24-25, 2007, which had been drafted by the present writer.2 It was very significant that US institutional forces acted at that time to prevent the rogue B-52 from proceeding on its way towards the Middle East. -

In Iran, Jailed Dual Nationals Are Pawns in Power Struggle

August 28, 2016 17 News & Analysis Iran In Iran, jailed dual nationals are pawns in power struggle Gareth Smyth ish charitable foundation worker; Homa Hoodfar, an Iranian-Canadi- an social anthropologist; and Robin London Reza Shahini, an Iranian-American citizen. hen US Republican Iran’s execution of Amiri on presidential candi- August 3rd was announced by date Donald Trump his mother, who said he had told suggested leaked e- her days earlier that his ten-year mail messages from sentence for spying had been in- Whis Democratic rival Hillary Clinton creased to capital punishment. may have led Iran to hang Shahram The hanging was confirmed by a Amiri, he made the executed Ira- judiciary spokesman, who said the nian nuclear scientist’s fate part of scientist had “passed on our coun- the US election. Amiri’s death and try’s most crucial intelligence”, the mysterious events that led up presumably about the nuclear pro- to it, however, are also caught up in gramme, “to the enemy”. the factional battles in Tehran. Many reformists in Iran argue Amiri became the that the “principlists” use many latest twist in the levers to undermine their oppo- Clinton e-mail saga. nents, including the pro-reform president, Hassan Rohani, who Amiri then became the lat- faces re-election in May. est twist in the Clinton e-mail According to this analysis, Ami- saga, which began in 2015 when it ri’s execution focuses attention on emerged she used a private e-mail threats from the United States and address while secretary of State undermines Rohani’s approach under US President Barack Obama.