Loons: Wildlife Notebook Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point Reyes National Seashore Bird List

Birds of Point Reyes National Seashore Gaviidae (Loons) Alcedinidae (Kingfishers) Podicipedidae (Grebes) Picidae (Woodpeckers) Diomedeidae (Albatrosses) Tyrannidae (Tyrant Flycatcher) Procellariidae (Shearwaters, Petrels) Alaudidae (Larks) Hydrobatidae (Storm Petrels) Hirundinidae (Swallows) Sulidae (Boobies, Gannets) Laniidae (Shrikes) Pelecanidae (Pelicans) Vireonidae (Vireos) Phalacrocoracidae (Cormorants) Corvidae (Crows, Jays) Fregatidae (Frigate Birds) Paridae (Chickadees, Titmice) Ardeidae (Herons, Bitterns, & Egrets) Aegithalidae (Bushtits) Threskiornithidae (Ibises, Spoonbills) Sittidae (Nuthatches) Ciconiidae (Storks) Certhiidae (Creepers) Anatidae (Ducks, Geese, Swans) Troglodytidae (Wrens) Cathartidae (New World Vultures) Cinclidae (Dippers) Accipitridae (Hawks, Kites, Eagles) & Regulidae (Kinglets) Falconidae (Caracaras, Falcons) Sylviidae (Old World Warblers, Gnatcatchers) Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Turdidae (Thrushes) Rallidae (Rails, Gallinules, Coots) Timaliidae (Babblers) Gruidae (Cranes) Mimidae (Mockingbirds, Thrashers) Charadriidae (Lapwings, Plovers) Motacillidae (Wagtails, Pipits) Haematopodidae (Oystercatcher) Bombycillidae (Waxwings) Recurvirostridae (Stilts, Avocets) Ptilogonatidae (Silky-flycatcher) Scolopacidae (Sandpipers, Phalaropes) Parulidae (Wood Warblers) Laridae (Skuas, Gulls, Terns, Skimmers) Cardinalidae (Cardinals) Alcidae (Auks, Murres, Puffins) Emberizidae (Emberizids) Columbidae (Pigeons, Doves) Fringillidae (Finches) Cuculidae (Cuckoos, Road Runners, Anis) NON-NATIVES Tytonidae (Barn Owls) -

The Cycle of the Common Loon (Brochure)

ADIRONDACK LOONS AND LAKES FOR MORE INFORMATION: NEED YOUR HELP! lthough the Adirondack Park provides A suitable habitat for breeding loons, the summering population in the Park still faces many challenges. YOU CAN HELP! WCS’ Adirondack Loon Conservation Program Keep Shorelines Natural: Help maintain ~The Cycle of the this critical habitat for nesting wildlife and 7 Brandy Brook Ave, Suite 204 for the quality of our lake water. Saranac Lake, NY 12983 Common Loon~ (518) 891-8872, [email protected] Out on a Lake? Keep your distance (~100 feet or more) from loons and other wildlife, www.wcs.org/adirondackloons so that you do not disturb them. The Wildlife Conservation Society’s Adirondack Going Fishing? Loon Conservation Program is dedicated to ∗ Use Non-Lead Fishing Sinkers and improving the overall health of the environment, Jigs. Lead fishing tackle is poisonous to particularly the protection of air and water loons and other wildlife when quality, through collaborative research and accidentally ingested. education efforts focusing on the natural history ∗ Pack Out Your Line. Invisible in the of the Common Loon (Gavia immer) and water, lost or cut fishing line can conservation issues affecting loon populations entangle loons and other wildlife, often and their aquatic habitats. with fatal results. THE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY IS Be an Environmentally Wise Consumer: GRATEFUL TO ITS COLLABORATORS FOR THEIR Many forms of environmental pollution SUPPORT OF THE LOON PROGRAM: result from the incineration of fossil Natural History Museum of the Adirondacks - fuels, primarily from coal-fired power The W!ld Center plants and vehicles, negatively affecting www.wildcenter.org A guide to the seasonal Adirondack ecosystems and their wild NYS Dept. -

![LOONS and GREBES [ ] Common Loon [ ] Pied-Billed Grebe---X](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1406/loons-and-grebes-common-loon-pied-billed-grebe-x-351406.webp)

LOONS and GREBES [ ] Common Loon [ ] Pied-Billed Grebe---X

LOONS and GREBES [ ] Common Merganser [ ] Common Loon [ ] Ruddy Duck---x OWLS [ ] Pied-billed Grebe---x [ ] Barn Owl [ ] Horned Grebe HAWKS, KITES and EAGLES [ ] Eared Grebe [ ] Northern Harrier SWIFTS and HUMMINGBIRDS [ ] Western Grebe [ ] Cooper’s Hawk [ ] White-throated Swift [ ] Clark’s Grebe [ ] Red-shouldered Hawk [ ] Anna’s Hummingbird---x [ ] Red-tailed Hawk KINGFISHERS PELICANS and CORMORANTS [ ] Golden Eagle [ ] Belted Kingfisher [ ] Brown Pelican [ ] American Kestrel [ ] Double-crested Cormorant [ ] White-tailed Kite WOODPECKERS [ ] Acorn Woodpecker BITTERNS, HERONS and EGRETS PHEASANTS and QUAIL [ ] Red-breasted Sapsucker [ ] American Bittern [ ] Ring-necked Pheasant [ ] Nuttall’s Woodpecker---x [ ] Great Blue Heron [ ] California Quail [ ] Great Egret [ ] Downy Woodpecker [ ] Snowy Egret RAILS [ ] Northern Flicker [ ] Sora [ ] Green Heron---x TYRANT FLYCATCHERS [ ] Black-crowned Night-Heron---x [ ] Common Moorhen Pacific-slope Flycatcher [ ] American Coot---x [ ] NEW WORLD VULTURES [ ] Black Phoebe---x Say’s Phoebe [ ] Turkey Vulture SHOREBIRDS [ ] [ ] Killdeer---x [ ] Ash-throated Flycatcher WATERFOWL [ ] Greater Yellowlegs [ ] Western Kingbird [ ] Greater White-fronted Goose [ ] Black-necked Stilt SHRIKES [ ] Ross’s Goose [ ] Spotted Sandpiper Loggerhead Shrike [ ] Canada Goose---x [ ] Least Sandpiper [ ] [ ] Wood Duck [ ] Long-billed Dowitcher VIREOS Gadwall [ ] [ ] Wilson’s Snipe [ ] Warbling Vireo [ ] American Wigeon [ ] Mallard---x GULLS and TERNS JAYS and CROWS [ ] Cinnamon Teal [ ] Mew Gull [ ] Western Scrub-Jay---x -

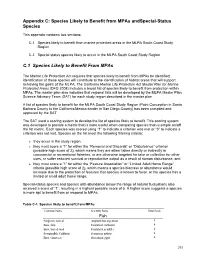

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Pacific Loon

Pacific Loon (Gavia pacifica) Vulnerability: Presumed Stable Confidence: Moderate The Pacific Loon is the most common breeding loon in Arctic Alaska, nesting throughout much of the state (Russell 2002). This species typically breeds on lakes that are ≥1 ha in size in both boreal and tundra habitats. They are primarily piscivorous although they are known to commonly feed chicks invertebrates (D. Rizzolo and J. Schmutz, unpublished data). Many Pacific Loons spend their winters in offshore waters of the west coast of Canada and the U.S. (Russell 2002). The most recent Alaska population estimate is 100-125,000 individuals (Ruggles and Tankersley 1992) with ~ 69,500 on the Arctic Coastal Plain specifically (Groves et al. 1996). encroachment (Tape et al. 2006) into tundra habitats. Although small fish make up a significant part of the Pacific Loon diet, they also eat many invertebrates (e.g., caddis fly larvae, nostracods) and so, unlike some other loon species, exhibit enough flexibility in their diet that they would likely be able to adjust to climate-mediated changes in prey base. S. Zack @ WCS Range: We used the extant NatureServe map for the assessment as it matched other range map sources and descriptions (Johnson and Herter 1989, Russell 2002). Physiological Hydro Niche: Among the indirect exposure and sensitivity factors in the assessment (see table on next page), Pacific Loons ranked neutral in most categories with the exception of physiological hydrologic niche for which they were evaluated to have a “slightly to greatly increased” vulnerability. This response was driven primarily by this species reliance on small water bodies (typically <1ha) for breeding Disturbance Regime: Climate-mediated and foraging. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

Final Restoration Plan for Common Loon and Other Birds Impacted by the Bouchard Barge 120 (B-120) Oil Spill, Buzzards Bay Massachusetts and Rhode Island

FINAL RESTORATION PLAN for COMMON LOON (Gavia immer) and OTHER BIRDS IMPACTED BY THE BOUCHARD BARGE 120 (B-120) OIL SPILL BUZZARDS BAY MASSACHUSETTS and RHODE ISLAND June 2020 Prepared by: United States Fish and Wildlife Service Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Lead Administrative Trustee) Executive Summary In April 2003, the Bouchard Barge‐120 (B‐120) oil spill (the Spill) affected more than 100 miles of Buzzards Bay and its shoreline and nearby coastal waters in both Massachusetts (MA) and Rhode Island (RI). Birds were exposed to and ingested oil as they foraged, nested, and/or migrated through the area. Species of birds estimated to have been killed in the greatest numbers included common loon (Gavia immer), common and roseate terns (Sterna hirundo and Sterna dougallii), and other birds such as common eider (Somateria mollissima), black scoter (Melanitta americana), and red‐throated loon (Gavia stellata). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) (acting through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [USFWS]), the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (acting through the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs [EEA]), and the State of Rhode Island serve as the natural resource Trustees (Trustees) responsible under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA) (33 U.S.C. § 2701, et seq.) for ensuring the natural resources injured from the Spill are restored. As a designated Trustee, each agency is authorized to act on behalf of the public under State1 and/or Federal law to assess and recover natural resource damages, and to plan and implement actions to restore, rehabilitate, replace, or acquire the equivalent of the natural resources or services injured or lost as a result of an unpermitted discharge of oil. -

Beached Bird Guide for Northern Lake Michigan

Beached Bird Guide for Northern Lake Michigan Prepared by Common Coast Research & Conservation In association with the Grand Traverse Bay Botulism Network © 2008 Common Coast Research & Conservation How to use this guide This guide was developed to aid with the field identification of the most common waterbird species implicated in botulism E die-offs on northern Lake Michigan. The guide is not intended to be a comprehensive treatment of all species you may encounter in the field. For birds not treated in this guide please document with photographs and/or submit carcasses to the nearest Michigan Department of Natural Resources Field Office for identification and/or testing for botulism (see manual). The emphasis of this guide is on differences in bill structure among the various waterbird species. The bill plates are drawn to actual size - we recommend laminating the guide for use in the field. Placing the bills of unknown species directly on the plates will facilitate identification. Please keep in mind some variation among individuals is to be expected. Photographs of unknown species are helpful for later identification. Bird Topography tarsus crown bill (upper and lower mandibles) foot bill margin cheek throat wing coverts (lesser) secondaries webbed foot lobed foot primaries (loons, ducks, gulls) (grebes) Loons and Grebes Birds with dagger-like bills Description: Adult Common Loon bill large, dagger-like, mandible edges smooth feet webbed tarsus narrow, flat Plumage variation (adult vs. juvenile): Look at wing coverts: Adult – well-defined white "windows" (see photo) Juvenile - lacks defined white "windows" Similar species: Red-throated Loon – bill smaller (rarely found) Red-necked Grebe – feet lobed, bill smaller Description: Red-throated Loon bill dagger-like, slightly upturned, mandible edges smooth feet webbed tarsus narrow, flat Similar species: Common Loon - larger; bill heavier, not upturned Red-necked Grebe – feet lobed , bill yellowish NOTE: Rarely encountered. -

Were Sauropod Dinosaurs Responsible for the Warm Mesozoic Climate?

Journal of Palaeogeography 2012, 1(2): 138-148 DOI: 10.3724/SP.J.1261.2012.00011 Biopalaeogeography and palaeoclimatology Were sauropod dinosaurs responsible for the warm Mesozoic climate? A. J. (Tom) van Loon* Geological Institute, Adam Mickiewicz University, Maków Polnych 16, 61-606, Poznan, Poland Abstract It was recently postulated that methane production by the giant Mesozoic sau- ropod dinosaurs was larger than the present-day release of this greenhouse gas by nature and man-induced activities jointly, thus contributing to the warm Mesozoic climate. This conclusion was reached by correct calculations, but these calculations were based on unrealistic as- sumptions: the researchers who postulated this dinosaur-induced warm climate did take into account neither the biomass production required for the sauropods’ food, nor the constraints for the habitats in which the dinosaurs lived, thus neglecting the palaeogeographic conditions. This underlines the importance of palaeogeography for a good understanding of the Earth’s geological history. Key words sauropod dinosaurs, greenhouse conditions, methane, palaeogeography 1 Introduction* etc. Some of these compounds are thought to have contrib‑ uted to the global temperature rise that took place in the For a long time, geologists have wondered why highly 20th century, but the causal relationship is still hotly de‑ significant fluctuations in the global temperature occurred bated (Rothman, 2002). One of the reasons is that climate in the geological past. It was found by Milankovich (1930, models show significant shortcomings (especially when 1936, 1938) that the alternation of Pleistocene glacials and applied back in time). Another reason is that data (e.g. the interglacials can largely be understood on the basis of as‑ relationship between CO2 concentrations in the ice in cores tronomical factors. -

Bird List Lake Pepin IBA REGULAR

Important Bird Area - Bird List Lake Pepin IBA August 2010 Checklist of Minnesota Birds Compiled list from all Red: PIF Continental Importance available data sources (BOLD RED are Nesting Green: Stewardship Species Species as documented by Blue: BCR Important Species one of the sources) Purple: PIF Priority in one or more regions REGULAR Ducks, Geese, Swans Greater White-fronted Goose 1 Snow Goose 1 Ross's Goose Cackling Goose (tallgrass prairie) Canada Goose 1 Mute Swan Trumpeter Swan Tundra Swan 1 Wood Duck 1 Gadwall 1 American Wigeon 1 American Black Duck 1 Mallard 1 Blue-winged Teal 1 Cinnamon Teal Northern Shoveler 1 Northern Pintail 1 Green-winged Teal 1 Canvasback 1 Redhead 1 Ring-necked Duck 1 Greater Scaup 1 Lesser Scaup 1 Harlequin Duck Surf Scoter White-winged Scoter 1 Black Scoter Long-tailed Duck Bufflehead 1 Common Goldeneye 1 Page 1 of 12 Publication date January 2015 http://mn.audubon.org/ Important Bird Area - Bird List Lake Pepin IBA August 2010 Checklist of Minnesota Birds Compiled list from all Red: PIF Continental Importance available data sources (BOLD RED are Nesting Green: Stewardship Species Species as documented by Blue: BCR Important Species one of the sources) Purple: PIF Priority in one or more regions Hooded Merganser 1 Common Merganser 1 Red-breasted Merganser 1 Ruddy Duck 1 Partridge, Grouse, Turkey Gray Partridge 1 Ring-necked Pheasant 1 Ruffed Grouse 1 Spruce Grouse Sharp-tailed Grouse Greater Prairie-Chicken Wild Turkey 1 Loons Red-throated Loon Pacific Loon Common Loon 1 Grebes Pied-billed Grebe 1 Horned -

The Fossil Loon, Colymboides Minutes

Nov., 1956 413 THE FOSSIL LOON, COLYMBOIDES MINUTUS By ROBERT W. STORER In recent years, most taxonomic work on birds has been at the level of the species and subspecies,while the interrelationships of the major groups of birds have received relatively little attention. The classifications set up before Darwin’s time were based purely on similarities in structure; but with the acceptance of the concept of organic evolution, the corollary of convergence slowly became understood. This idea that two or more unrelated groups of organisms could, in the course of evolution, become super- ficially similar in both habits and structure is, of course, very important. Thus in order to understand the true relationship between two groups, common characters which are the result of convergent evolution must be distinguished from more conservative features which are indicators of actual phylogenetic relationships. The diving birds provide excellent examples of convergence. Until the appearance of the fourth edition of the Check-List of North American Birds in 193 1, the loons, grebes, and auks were all grouped in one order by most American ornithologists. Members of the auk tribe, which, unlike the loons and grebes, regularly use their wings for prop& sion under water, are now believed to be related to the gulls. The loons and grebes have been put in separate orders, which, however, are kept side by side in the classifications of most workers. The reasons for separating loons from grebes are many and fundamental. Among them are the differences in the texture of the plumage, the form of the tail feathers, the location of the nest, the number of eggs, and the webbed versus lobed toes. -

Alaska Loon and Grebe Watch Instructions for Volunteers

Alaska Loon and Grebe Watch Instructions for Volunteers Identifying Loons and Grebes There are 3 loon and 2 grebes species that typically occur in southcentral Alaska during the summer. These are the Common Loon (large, black- headed), the Pacific Loon (gray-headed with white bars on back, formerly called the Arctic Loon), Red-throated Loon (smaller, gray-headed), Red- necked Grebe (chestnut neck, white cheek patches), and the Horned Grebe (smaller grebe, yellow-cheek patch). Please see attached identification guide to familiarize yourself with these birds. Finding Loon and Grebe Nests The best time to watch for nesting loons and grebe is in May and June. This is when loons and grebe will be incubating eggs. If the loons are incubating, you are most likely to see only one loon out on the lake during this time. Both adults share in the incubation duties and will exchange places periodically. Careful watching from a distance with binoculars will often reveal the nest location as the loons go to and from the nest. If you want to search for a nest, wait until after the loons are done nesting, then investigate the likely areas right along the shoreline for a large bowl made of mud or open space with eggshell fragments. Grebes build floating nests which are typically visible from the shoreline. Both adults also share nest building, incubation, and parental care duties. Often loon and grebe pairs will reuse the same area for nesting year after year. If the eggs are lost due to predation or accidental causes, loons and grebes will usually renest (potentially in a different spot).