The Cycle of the Common Loon (Brochure)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Migration Strategy, Diet & Foraging Ecology of a Small

The Migration Strategy, Diet & Foraging Ecology of a Small Seabird in a Changing Environment Renata Jorge Medeiros Mirra September 2010 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Cardiff School of Biosciences, Cardiff University UMI Number: U516649 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516649 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declarations & Statements DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed j K>X).Vr>^. (candidate) Date: 30/09/2010 STATEMENT 1 This thasjs is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree o f ..................... (insertMCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed . .Ate .^(candidate) Date: 30/09/2010 STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledgedjjy explicit references. Signe .. (candidate) Date: 30/09/2010 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. -

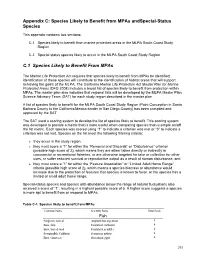

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Pacific Loon

Pacific Loon (Gavia pacifica) Vulnerability: Presumed Stable Confidence: Moderate The Pacific Loon is the most common breeding loon in Arctic Alaska, nesting throughout much of the state (Russell 2002). This species typically breeds on lakes that are ≥1 ha in size in both boreal and tundra habitats. They are primarily piscivorous although they are known to commonly feed chicks invertebrates (D. Rizzolo and J. Schmutz, unpublished data). Many Pacific Loons spend their winters in offshore waters of the west coast of Canada and the U.S. (Russell 2002). The most recent Alaska population estimate is 100-125,000 individuals (Ruggles and Tankersley 1992) with ~ 69,500 on the Arctic Coastal Plain specifically (Groves et al. 1996). encroachment (Tape et al. 2006) into tundra habitats. Although small fish make up a significant part of the Pacific Loon diet, they also eat many invertebrates (e.g., caddis fly larvae, nostracods) and so, unlike some other loon species, exhibit enough flexibility in their diet that they would likely be able to adjust to climate-mediated changes in prey base. S. Zack @ WCS Range: We used the extant NatureServe map for the assessment as it matched other range map sources and descriptions (Johnson and Herter 1989, Russell 2002). Physiological Hydro Niche: Among the indirect exposure and sensitivity factors in the assessment (see table on next page), Pacific Loons ranked neutral in most categories with the exception of physiological hydrologic niche for which they were evaluated to have a “slightly to greatly increased” vulnerability. This response was driven primarily by this species reliance on small water bodies (typically <1ha) for breeding Disturbance Regime: Climate-mediated and foraging. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

Final Restoration Plan for Common Loon and Other Birds Impacted by the Bouchard Barge 120 (B-120) Oil Spill, Buzzards Bay Massachusetts and Rhode Island

FINAL RESTORATION PLAN for COMMON LOON (Gavia immer) and OTHER BIRDS IMPACTED BY THE BOUCHARD BARGE 120 (B-120) OIL SPILL BUZZARDS BAY MASSACHUSETTS and RHODE ISLAND June 2020 Prepared by: United States Fish and Wildlife Service Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Lead Administrative Trustee) Executive Summary In April 2003, the Bouchard Barge‐120 (B‐120) oil spill (the Spill) affected more than 100 miles of Buzzards Bay and its shoreline and nearby coastal waters in both Massachusetts (MA) and Rhode Island (RI). Birds were exposed to and ingested oil as they foraged, nested, and/or migrated through the area. Species of birds estimated to have been killed in the greatest numbers included common loon (Gavia immer), common and roseate terns (Sterna hirundo and Sterna dougallii), and other birds such as common eider (Somateria mollissima), black scoter (Melanitta americana), and red‐throated loon (Gavia stellata). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) (acting through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [USFWS]), the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (acting through the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs [EEA]), and the State of Rhode Island serve as the natural resource Trustees (Trustees) responsible under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA) (33 U.S.C. § 2701, et seq.) for ensuring the natural resources injured from the Spill are restored. As a designated Trustee, each agency is authorized to act on behalf of the public under State1 and/or Federal law to assess and recover natural resource damages, and to plan and implement actions to restore, rehabilitate, replace, or acquire the equivalent of the natural resources or services injured or lost as a result of an unpermitted discharge of oil. -

The Common Loon in New York State

THE COMMON LOON IN NEW YORK STATE For a number of years a committee of the Federation of New York State Bird Clubs has been planning a new Birds of New York State to succeed the monumental two volume work by E. H. Eaton, published by the State Museum a half century ago. This new book is not envisioned as an all-encompassing state book in the classic tradition. The day is long past for lavish volumes, liberally illus- trated, describing and portraying in detail the plumages, the habits, the life histories, and the economic importance of each species ever recorded in the state, just as if there were no other readily-available sources for this informa- tion. The committee believes that what a present-day state book should do is to concentrate on what is specifically germane to the ornithology of the state. It should be an inventory of the state list, a census of the breeding species, an estimate of populations wherever possible, a guide to the seasonal calendar of the species found in New York, an atlas of breeding ranges and migration routes, and an accounting of the unusual species that have been recorded within our boundaries. It should additionally give an accounting of the species normally to be found in the various ecological associations of the state. All this to give as accurate as possible a picture, and historical record, of the bird life of the state as it exists just prior to publication. It should certainly record changes that have taken place over the years, when known, and might even venture a prediction or two about the future. -

Beached Bird Guide for Northern Lake Michigan

Beached Bird Guide for Northern Lake Michigan Prepared by Common Coast Research & Conservation In association with the Grand Traverse Bay Botulism Network © 2008 Common Coast Research & Conservation How to use this guide This guide was developed to aid with the field identification of the most common waterbird species implicated in botulism E die-offs on northern Lake Michigan. The guide is not intended to be a comprehensive treatment of all species you may encounter in the field. For birds not treated in this guide please document with photographs and/or submit carcasses to the nearest Michigan Department of Natural Resources Field Office for identification and/or testing for botulism (see manual). The emphasis of this guide is on differences in bill structure among the various waterbird species. The bill plates are drawn to actual size - we recommend laminating the guide for use in the field. Placing the bills of unknown species directly on the plates will facilitate identification. Please keep in mind some variation among individuals is to be expected. Photographs of unknown species are helpful for later identification. Bird Topography tarsus crown bill (upper and lower mandibles) foot bill margin cheek throat wing coverts (lesser) secondaries webbed foot lobed foot primaries (loons, ducks, gulls) (grebes) Loons and Grebes Birds with dagger-like bills Description: Adult Common Loon bill large, dagger-like, mandible edges smooth feet webbed tarsus narrow, flat Plumage variation (adult vs. juvenile): Look at wing coverts: Adult – well-defined white "windows" (see photo) Juvenile - lacks defined white "windows" Similar species: Red-throated Loon – bill smaller (rarely found) Red-necked Grebe – feet lobed, bill smaller Description: Red-throated Loon bill dagger-like, slightly upturned, mandible edges smooth feet webbed tarsus narrow, flat Similar species: Common Loon - larger; bill heavier, not upturned Red-necked Grebe – feet lobed , bill yellowish NOTE: Rarely encountered. -

Loons: Wildlife Notebook Series

Loons Loons are known as “spirits of the wilderness,” and it is fitting that Alaska has all five species of loons found in the world. Loons are an integral part of Alaska's wilderness—a living symbol of Alaska's clean water and high level of environmental quality. Loons, especially common loons, are most famous for their call. The cry of a loon piercing the summer twilight is one of the most thrilling sounds of nature. The sight or sound of one of these birds in Alaskan waters gives a special meaning to many, as if it were certifying the surrounding as a truly wild place. Description: Loons have stout bodies, long necks, pointed bills, three-toed webbed feet, and spend most of their time afloat. Loons are sometimes confused with cormorants, mergansers, grebes, and other diving water birds. Loons have solid bones, and compress the air out of their feathers to float low in the water. A loon's bill is held parallel to the water, but the cormorant holds its hooked bill at an angle. Mergansers have narrower bills and a crest. Grebes, also diving water birds, are relatively short-bodied. Loons can be distinguished from ducks in flight by their slower wing beat and low-slung necks and heads. The five species of loons found in Alaska are the common, yellow-billed, red-throated, pacific and arctic. Common loons (Gavia immer), have deep black or dark green heads and necks and dark backs with an intricate pattern of black and white stripes, spots, squares, and rectangles. The yellow-billed loon (Gavia adamsii) is similar, but it has white spots on its back and a straw-yellow bill even in winter. -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Bird List Lake Pepin IBA REGULAR

Important Bird Area - Bird List Lake Pepin IBA August 2010 Checklist of Minnesota Birds Compiled list from all Red: PIF Continental Importance available data sources (BOLD RED are Nesting Green: Stewardship Species Species as documented by Blue: BCR Important Species one of the sources) Purple: PIF Priority in one or more regions REGULAR Ducks, Geese, Swans Greater White-fronted Goose 1 Snow Goose 1 Ross's Goose Cackling Goose (tallgrass prairie) Canada Goose 1 Mute Swan Trumpeter Swan Tundra Swan 1 Wood Duck 1 Gadwall 1 American Wigeon 1 American Black Duck 1 Mallard 1 Blue-winged Teal 1 Cinnamon Teal Northern Shoveler 1 Northern Pintail 1 Green-winged Teal 1 Canvasback 1 Redhead 1 Ring-necked Duck 1 Greater Scaup 1 Lesser Scaup 1 Harlequin Duck Surf Scoter White-winged Scoter 1 Black Scoter Long-tailed Duck Bufflehead 1 Common Goldeneye 1 Page 1 of 12 Publication date January 2015 http://mn.audubon.org/ Important Bird Area - Bird List Lake Pepin IBA August 2010 Checklist of Minnesota Birds Compiled list from all Red: PIF Continental Importance available data sources (BOLD RED are Nesting Green: Stewardship Species Species as documented by Blue: BCR Important Species one of the sources) Purple: PIF Priority in one or more regions Hooded Merganser 1 Common Merganser 1 Red-breasted Merganser 1 Ruddy Duck 1 Partridge, Grouse, Turkey Gray Partridge 1 Ring-necked Pheasant 1 Ruffed Grouse 1 Spruce Grouse Sharp-tailed Grouse Greater Prairie-Chicken Wild Turkey 1 Loons Red-throated Loon Pacific Loon Common Loon 1 Grebes Pied-billed Grebe 1 Horned -

Molts and Plumages of Ducks (Anatinae) Author(S): Peter Pyle Source: Waterbirds, 28(2):208-219

Molts and Plumages of Ducks (Anatinae) Author(s): Peter Pyle Source: Waterbirds, 28(2):208-219. 2005. Published By: The Waterbird Society DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2005)028[0208:MAPODA]2.0.CO;2 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/ full/10.1675/1524-4695%282005%29028%5B0208%3AMAPODA%5D2.0.CO %3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/ page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non- commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Molts and Plumages of Ducks (Anatinae) PETER PYLE The Institute for Bird Populations, P.O. Box 1436, Point Reyes Station, CA 94956, USA Internet: [email protected] Abstract.—Ducks are unusual in that males of many species acquire brightly pigmented plumages in autumn rather than in spring. This has led to confusion in defining molts and plumages, using both traditional European terminology and that proposed by Humphrey and Parkes (1959). -

Aging, Sexing, and Molt

Aging, Sexing, and Molt Identification of birds not only means identifying the species of an change colors for territorial or sexual displays. The importance of individual, but also can include identifying its subspecies, sex, and these factors to a bird’s fitness will influence the frequency and age. Field identification of the age and sex of a bird can be impor- extent of molts. A yearly molt is generally sufficient to offset nor- tant for studying many aspects of avian ecology and evolution, mal rates of feather wear. Multiple molts in a year occur in birds including life history evolution, reproductive ecology, and behav- using seasonal plumage displays (territorial defense or sexual ioral ecology. Ornithologists use a variety of characteristics to attraction), in birds occupying harsh habitats (grasslands or identify, sex, and age birds (Table 1). deserts), or in birds that undertake long migrations. Table 1. Features usefulful for identifying, aging, and sexing birds. Identification Character Species Subspecies Sex Age Molt and Plumage Patterns Plumage coloration • • • • Feather wear • Feather shape • Other Features Size (wing, tail, weight, leg, bill) • • • • Skull ossification • Cloacal protuberance and brood patch • • Gape • • Iris color •• Song • • • Geographic location • • Molt and Plumage Patterns In the temperate zone, the proximal cue for molt initiation is Feathers are not permanent structures, but are periodically shed day length, which has an effect on the hormone levels that ulti- and replaced. The process of shedding and replacing worn feathers mately control molt progression. Molting is very costly. The bird is called molting, and the feather coats worn between molts are replaces 25 – 40 percent of its dry mass, drawing on protein and called plumages.