The Refinery Movement in Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Nepali Migration: Assimilation with the Assamese Society a Study of Sonitpur and Tinsukia Districts of Assam

Himalayan Journal of Development and Democracy, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2011 Dynamics of Nepali Migration: Assimilation with the Assamese Society A Study of Sonitpur and Tinsukia Districts of Assam Monimala Devi 25 DDR College, India Abstract Migration is an ancient global flow contributing to economic development, and over the ages its form and impetus have changed significantly. Migration brings both qualitative and quantitative changes in the socio- economic and demographic characteristics of a region. Thus, it is now recognized as an important factor in determining plans for social, economic and political development, especially in developing countries. Migration studies have attracted much attention in the recent studies of the world as it has shaped human civilization all over the world. Although, migration has been reasoned for political, economic and various other conflicts, it is important to understand the dynamics of population change in the form of migration for resolving ethnic, religious and military conflicts across the globe. Assam had a long history of receiving migrants, however in the pre- colonial times the inflows were smaller and people assimilated more imperceptibly. The Nepali migrants who came during the colonial period assimilated into the host society and contributed to the social, economic and political development of the state. The Nepali migrants who came during the colonial period assimilated into the host society and contributed to the social, economic and political development of the state. The present study attempts to understand the Nepali migration from the historical perspective and at the same time comprehend the mechanism in the recent past in its transformative character particularly in the Sonitpur and Tinsukia districts of Assam. -

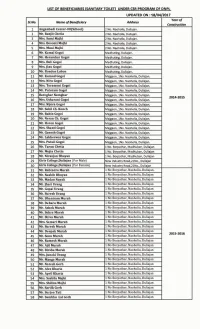

CSR Beneficiaries

Year of Sl.No Name of Beneficiaries Name of the Area Construction Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 59 Mr. Krishna Gogoi. Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 60 Mr. Lalit Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 61 Mr. Probitra Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 62 Mr. Suran Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 63 Mr. Naren Guwala Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 64 Mr. Haren Hazarika Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 65 Mr. Hemanta Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 66 Mr. Ramesh Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 67 Mr. Bagadhar Guwala Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 68 Mr. Haren Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 69 Mr. Puneswar Nath Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 70 Mr. Lakheswar Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 71 Mr. Mintu Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 72 Mr. Chandra Nath Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 73 Mr. Dembeswar Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 2016-2017 74 Mr. Mulan Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 75 Mr. Nila Kanta Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 76 Mr. Golap Gogoi Dist. Sivsagar (Assam) Mantonia Adarsha Gaon, P.O.: Deoraja. 77 Mrs. Hadori Gogoi Dist. -

Brahmaputra and the Socio-Economic Life of People of Assam

Brahmaputra and the Socio-Economic Life of People of Assam Authors Dr. Purusottam Nayak Professor of Economics North-Eastern Hill University Shillong, Meghalaya, PIN – 793 022 Email: [email protected] Phone: +91-9436111308 & Dr. Bhagirathi Panda Professor of Economics North-Eastern Hill University Shillong, Meghalaya, PIN – 793 022 Email: [email protected] Phone: +91-9436117613 CONTENTS 1. Introduction and the Need for the Study 1.1 Objectives of the Study 1.2 Methodology and Data Sources 2. Assam and Its Economy 2.1 Socio-Demographic Features 2.2 Economic Features 3. The River Brahmaputra 4. Literature Review 5. Findings Based on Secondary Data 5.1 Positive Impact on Livelihood 5.2 Positive Impact on Infrastructure 5.2.1 Water Transport 5.2.2 Power 5.3 Tourism 5.4 Fishery 5.5 Negative Impact on Livelihood and Infrastructure 5.6 The Economy of Char Areas 5.6.1 Demographic Profile of Char Areas 5.6.2 Vicious Circle of Poverty in Char Areas 6. Micro Situation through Case Studies of Regions and Individuals 6.1 Majuli 6.1.1 A Case Study of Majuli River Island 6.1.2 Individual Case Studies in Majuli 6.1.3 Lessons from the Cases from Majuli 6.1.4 Economics of Ferry Business in Majuli Ghats 6.2 Dhubri 6.2.1 A Case Study of Dhubri 6.2.2 Individual Case Studies in Dhubri 6.2.3 Lessons from the Cases in Dhubri 6.3 Guwahati 6.3.1 A Case of Rani Chapari Island 6.3.2 Individual Case Study in Bhattapara 7. -

Urbanisation and Growth of Small Towns in Assam, India

URBANISATION AND GROWTH OF SMALL TOWNS IN ASSAM, INDIA. Rinku Manta Research Scholar, Deptt. Of Geography Guwahati University Assam, India. [email protected] Dr. Jnanshree Borah, Associate Professor, Deptt. Of Geography Arya Vidyapeeth College Dr.Jayashree Bora, Associate Professor, Deptt. Of Geography, Cotton College Guwahati. INTRODUCTION:- Urbanisation is the process by which an increasing proportion of the country’s population starts residing in urban areas. “Understanding of Urbanisation” (Jha, 2006), the term is related to the core concern of Urban Geography. It stands for the study of Urban Concentration and Urban phenomena. By Urban Concentration what is meant in the different forms of urban setting; and by urban phenomena we mean all those processes that contribute to the development of urban centers and their resultant factors. Thus the scope of the term is certainly comprehensive. (Mallick, 1981) According to Census an urban area was determined based on two important criteria, namely: (i) statutory administration; (ii) certain economic and demographic indicators. The first criterion includes civic status of towns, and the second entails characteristics like population size, density of population, and percentage of the workforce in the non-agricultural sector. (Khawas V. 2002) India shares most characteristic features of urbanisation in the developing countries. Number of urban agglomeration /town has grown from 1827 in 1901 to 5161 in 2001. Out of the total 5161 towns in 2001, 3800 are statutory towns and 1361 are census towns. The number of statutory towns and census towns in 1991 was 2987 and 1702 respectively. The number of total population has increased from 23.84 crores in 1901 to 102.7 crores in 2001 whereas number of population residing in urban areas has increased from 2.58 crores in 1901 to 28.53 crore in 2001. -

For Rallis India Geophysics Department Limited (A Tata Group of Companies) in Mumbai

Volume 35, No. 7 Stop Press Mar. '06 - Apr. '06 Shri J K Talukdar is OIL's new Director (HR & BD) COVER : Shri J K Talukdar has been appointed as Director (Human Resource & Business Development) of Oil India Limited. A collage of pictures that Prior to his appointment as Director (HR & BD), Shri Talukdar was heading the Company's operations in the reflects the diverse North East as Group General Manager. After obtaining a activity profile of the degree in Mechanical Engineering from Assam Engineering College, Shri Talukdar worked for Rallis India Geophysics Department Limited (a Tata Group of Companies) in Mumbai. He joined Oil India Limited in 1983 and since then worked in ... activities that take the different capacities as - Head of Materials & Contracts, Head of Kolkata Branch, Adviser to CMD, General Manager (Management Services), General Manager geoscientists to remote (Services), Group General Manager (Shared Services) and Head of Fields and inaccessible areas Headquarters. As Head of OIL's field headquarters, Shri Talukdar has been playing a pivotal role in implementing a number of new initiatives for organizational in search of the elusive growth. Shri Talukdar is well known for his analytical skills & problem solving abilities. He has exceptional distinction to carry out system study & implement black gold. the best practices to improve overall performance. Shri Talukdar took part in various management programmes in IIM Kolkata, Tata Management Training Centre, Pune; Administrative Staff College of India (ASCI), INSIDE Hyderabad. He also attended a three months course on Public Enterprise Management under British Council Scholarship in UK and another course Feature 2 - 5 conducted by ACSI in Italy, France and Switzerland. -

Imperialism, Geology and Petroleum: History of Oil in Colonial Assam

SPECIAL ARTICLE Imperialism, Geology and Petroleum: History of Oil in Colonial Assam Arupjyoti Saikia In the last quarter of the 19th century, Assam’s oilfields Assam has not escaped the fate of the newly opened regions of having its mineral resources spoken of in the most extravagant and unfounded became part of the larger global petroleum economy manner with the exception of coal. and thus played a key role in the British imperial – H B Medlicott, Geological Survey of India economy. After decolonisation, the oilfields not only he discovery of petroleum in British North East India (NE) turned out to be the subject of intense competition in a began with the onset of amateur geological exploration of regional economy, they also came to be identified with Tthe region since the 1820s. Like tea plantations, explora tion of petroleum also attracted international capital. Since the the rights of the community, threatening the federal last quarter of the 19th century, with the arrival of global techno structure and India’s development paradigm. This paper logy, the region’s petroleum fields became part of a larger global is an attempt to locate the history of Assam’s oil in the petroleum economy, and, gradually, commercial exploration of large imperial, global and national political economy. petroleum became a reality. It was a time when geologists had not yet succeeded in shaping an understanding of the science of It re-examines the science and polity of petroleum oil and its commercial possibilities. Over the next century, the exploration in colonial Assam. Assam oilfields played a key role in the British imperial economy. -

Socio-Economic and Demographic Status of Assam: a Comparative Analysis of Assam with India Dr

International Journal of Humanities & Social Science Studies (IJHSSS) A Peer-Reviewed Bi-monthly Bi-lingual Research Journal ISSN: 2349-6959 (Online), ISSN: 2349-6711 (Print) Volume-I, Issue-III, November 2014, Page No. 108-117 Published by Scholar Publications, Karimganj, Assam, India, 788711 Website: http://www.ijhsss.com Socio-Economic and Demographic status of Assam: A comparative analysis of Assam with India Dr. Soma Dhar Research Scholar, Department of Economics, Assam University, Silchar, India Abstract The status of various indicators like, Socio-economic height, representation of demographic, human development ranking etc. can give us a rough picture about our economy. Assam is one of among the eight Sister States of North East India. It is the land of hills, valleys, mighty river Brahmaputra. The paper is based on the secondary data. The broad objective of the paper is to highlight the various facts & figures of Assam and compare these with facts & figures of all India averages. The analysis of the data shows that, though in some cases the performance of state Assam is satisfactorily than the all India average. But in major other areas, the position and performance of Assam is not satisfactorily compared to the all India average. In case of various socio-economic, demographic, human development indicators Assam is far behind from India. Key Wards: Socio-economic condition, Demographic status, Human development rank, Gender development, Nutrition status etc. Socio-economic condition and representation of demographic, human development status etc. are some important indicators which help to measure the development level of any community or state. According to Afzal (1995) and Bose (2006) development of medical science has improved the longevity of human population at the same time there are strong and well documented associations between health and socio-economic and other factors. -

Ahom Royal Families in the Writings of American Baptist Missionaries (1836-1857)

ARTICLES / 2 Ahom Royal Families in the Writings of American Baptist Missionaries (1836-1857) Dr. Dipankar Gogoi* Introduction: The coming of the American Baptist Missionaries is an important event in the socio-religious and cultural history of Assam. The history of the Baptist Missionaries in Assam started after the arrival of Nathan Brown and O.T. Cutter at Sadiya with their families on March 23, 1836. Their main object was to preach Christianity at Sadiya with a hope to go to North Burma and South China. Thereafter Miles Bronson and Jacob Thomas came to Assam from America. Unfortunately Thomas died on the river just before reaching Sadiya. Bronson arrived at Sadiya on July 17, 1837. Thereafter different missionaries came to Assam from time to time. The prime object of the missionaries was to spread Christianity. The missionaries did a lot of activities to achieve their goal including learning of local languages, translation and writing of books related to the Christian literature, publication of books, establishment of schools, etc. Most of the experiences and activities of the early missionaries worked in Assam were published in the Baptist Missionary Magazine published in America which writings were referred as Journals. Besides journals, their personal letters, their books and the Orunudoi are very important to know about early mission activities in Assam. All the sources throw light not only on their activities but also on the contemporary Assam — the land and its people. During the time of missionaries coming, Assam was on new crossroads. The British already occupied the land and introduced new system of governance. -

201 Role and Current Status of Infrastructure in the Economy Of

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 9 Issue 9, September 2019, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Role and Current Status of Infrastructure in the Economy of Assam: A District level Analysis MridusmitaPatowary Abstract Infrastructure is needed for the up lifting of an economy. No country can progress without proper infrastructural facilities. Infrastructure development is required for the economic development of any country. In this paper, an attempt is made to make an assessment of the role of infrastructure (both economic and social) in economic development of Assam. The time considered in this study is 2016. In this study, a total number of 10 indicators are considered. Out of which six indicators are concerned with economic Keywords: infrastructure and the rest four indicators are concerned with social infrastructure. Under social infrastructure education and health infrastructure Infrastructural Development; is considered. Two indicators are considered for each education and health Economic Infrastructure, Social infrastructure. Economic infrastructure index and social infrastructure index Infrastructure were constructed using the Principal Component Analysis. In this paper, composite index is computed using principal component analysis and also the different categories of development is assessed which is classified under four heads- highly developed, middle level developed, developing and low developed categories respectively. The different categories were classified on the basis of the computed composite index. -

Vital Installations

DISTRICT: DIBRUGARH INFORMATION ON INDUSTRIES/VITAL INSTALLATIONS SL.NO. NAME REVENUE CIRCLE GAON PANCHAYAT VILLAGE NAME APDCL SUB STATIONS 8 FUEL JUNCTION DIBRUGARH EAST DIBRUGARH TOWN WARD 07 SL. NAME OF SUB- VOLTAGE EXISTING TRANSFORMER TOTAL MVA CAP OF NEAREST TOWN 9 MP JALAN DIBRUGARH EAST DIBRUGARH TOWN WARD 07 NO STATION LEVEL CAPACITY (MVA) IN 2008- TRANSFORMER 10 ORIENTAL AUTOMOBILES DIBRUGARH EAST DIBRUGARH TOWN WARD 07 2009 11 R.R. & CO. (MAIN) DIBRUGARH EAST DIBRUGARH TOWN WARD 07 0 RAJGARH 33/11 KV 1X5+1X2.5 7.5 NEAR NAMRUP 12 R.R. & CO. (MGSS) DIBRUGARH EAST DIBRUGARH TOWN WARD 15 1 KHOWANG 33/11 KV 2X3.15 6.3 KHOWANG 13 ASMINA FUELING STATION DIBRUGARH EAST DIBRUGARH TOWN WARD 22 2 DIGBOI 33/11 KV 2X5 10 DIGBOI 14 UDAYRAM RAWATMAL DIBRUGARH EAST PHUKANAR KHAT CHAULKHOWA GRANT GAON 3 MORAN 33/11 KV 2X5 10 MORAN 15 HAYWAY SERVICE STATION DIBRUGARH EAST MOHANBARI MOHANBARI 3/160 4 JOYPUR 33/11 KV 1X3.15 3.15 JOYPUR 16 MEDINI AUTOMOBILES TENGAKHAT TENGAKHAT NIZ-TENGAKHAT 5 NAHARKATIA 33/11 KV 1X5+1X2.5 7.5 NAHARKATIA 17 GIRIJA AUTOMOBILES TENGAKHAT TENGAKHAT NIZ-TENGAKHAT 6 MONABARI 33/11 KV 2X2.5 5 MOHANBARI 18 A.G. FILLING STATION TENGAKHAT DULIAJAN TOWN DULIAJAN TOWN 7 PHOOLBAGAN 33/11 KV 2X5 10 DIBRUGARH 19 BN SING SERVICE STATION TENGAKHAT DULIAJAN TOWN DULIAJAN TOWN 8 BHADOI 33/11 KV 2X5 10 DIBRUGARH PANCHALI 20 JAYANTA DUTTA FILLING TENGAKHAT DULIAJAN TOWN DULIAJAN TOWN SERVICE 9 NADUA 33/11 KV 1X2.5 2.5 DIBRUGARH 21 SANTI AUTO SERVICE TENGAKHAT DULIAJAN TOWN DULIAJAN TOWN 10 DIBRUGARH 33/11 KV 2X10 20 DIBRUGARH 22 BHADOI FUEL CENTRE TENGAKHAT BHADOI NAGAR BHADAI NAGAR 11 MOHANBARI 33/11 KV 1X2.5 2.5 DIBRUGARH 23 SING AUTO AGENCY TENGAKHAT DULIAJAN HOOGRIJAN 12 CHABUA 33/11 KV 2X2.5 5 CHABUA 24 R.R. -

Quarter No. BX1/BX2, Oil India Township Narangi, P.O. Udyanvihar, Guwahati, Assam – 781171 LETTER INVITING BID (LIB) No.A415/MS-T04/LIB-01Date:03.12.2015

Quarter No. BX1/BX2, Oil India Township Narangi, P.O. UdyanVihar, Guwahati, Assam – 781171 LETTER INVITING BID (LIB) No.A415/MS-T04/LIB-01Date:03.12.2015 The Letter Inviting Bid (LIB) is open only to Agencies to whom this LIB is issued in Physical Form SUBJECT: MANPOWER SUPPLY FOR CIVIL & STRUCTURAL WORKS FOR UPGRADING PUMP STATIONS/ TERMINALS OF NAHARKATIYA-BARAUNI CRUDE OIL PIPELINE (NBPS) BIDDING DOCUMENT NO. A415-EIS-19-42-MS-T04 OIL’s E-Tender No.:EIL9832L16 Dear Sir(s), 1.0 OIL India Ltd (OIL) is up-grading pumping stations/terminals situated on Naharkatiya- Barauni Crude Oil Pipeline (NBPL). 2.0 OIL has appointed Engineers India Limited (EIL) as their Consultant for implementation of the Project. 3.0 EIL on behalf of M/s OIL, invites Bids for the work as detailed in the Bidding Documentunder single stage two envelopes system bidding. The Bidding Document composes of two parts as per Master Index. 4.0 SALIENT DETAILS: MANPOWER SUPPLY FOR CIVIL & a) Name of Work : STRUCTURAL WORKS 4 (Four) monthsfrom date of issue of Fax b) Time Schedule : of Acceptance c) Sale period of Bidding Document From 07.12.2015 to 12.12.2015 Rs 3,51,450 (Indian Rupees Three Lakhs d) Bid Security / Earnest Money Deposit : Fifty one ThousandFour hundred Fiftyonly). Last Date and time of submission of e) : 16.12.2015up to15.00 Hrs., Bids 16.12.2015at 17.00 Hrs., In the presence of Bidder‘s Representativesat Opening of Un-priced Bids f) : Quarter No. BX1/BX2, Oil India Township Narangi, P.O. -

Assam Development Report

The Core Committee (Composition as in 2002) Dr. K. Venkatasubramanian Member, Planning Commission Chairman Shri S.C. Das Commissioner (P&D), Government of Assam Member Prof Kirit S. Parikh Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research Member Dr. Rajan Katoch Adviser (SP-NE), Planning Commission Member-Convener Ms. Somi Tandon for the Planning Commission and Shri H.S. Das & Dr. Surojit Mitra from the Government of Assam served as members of the Core Committee for various periods during 2000-2002. Project Team Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai Professor Kirit S. Parikh (Leader and Editor) Professor P. V. Srinivasan Professor Shikha Jha Professor Manoj Panda Dr. A. Ganesh Kumar Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, New Delhi Shri Sanjoy Hazarika Shri Biswajeet Saikia Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, Guwahati Dr. B. Sarmah Dr. Kalyan Das Professor Abu Nasar Saied Ahmed Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi Professor Atul Sarma Acknowledgements We thank Planning Commission and the Government of Assam for entrusting the task to prepare this report to Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR). We are particularly indebted to Dr. K. Venkatasubramanian, Member, Planning Commission and Chairman of the Core Committee overseeing the preparation of the Report for his personal interest in this project and encouragement and many constructive suggestions. We are extremely grateful to Dr. Raj an Katoch of the Planning Commission for his useful advice, overall guidance and active coordination of the project, which has enabled us to bring this exercise to fruition. We also thank Ms. Somi Tandon, who helped initiate the preparation of the Report, all the members of the Core Committee and officers of the State Plans Division of the Planning Commission for their support from time to time.