Factional Politics in Assam: a Study on the Asom Gana Parishad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

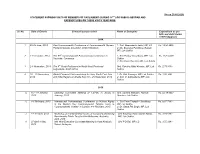

LIST of ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED for the POST of GD. IV of AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT of DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR

LIST OF ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR THE POST OF GD. IV OF AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT OF DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR Date of form Sl Post Registration No Candidate Name Father's Name Present Address Mobile No Date of Birth Submission 1 Grade IV 101321 RATUL BORAH NAREN BORAH VILL:-BORPATHAR NO-1,NARAYANPUR,GOSAIBARI,LAKHIMPUR,Assam,787033 6000682491 30-09-1978 18-11-2020 2 Grade IV 101739 YASHMINA HUSSAIN MUZIBUL HUSSAIN WARD NO-14, TOWN BANTOW,NORTH LAKHIMPUR,KHELMATI,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 6002014868 08-07-1997 01-12-2020 3 Grade IV 102050 RAHUL LAMA BIKASH LAMA 191,VILL NO 2 DOLABARI,KALIABHOMORA,SONITPUR,ASSAM,784001 9678122171 01-10-1999 26-11-2020 4 Grade IV 102187 NIRUPAM NATH NIDHU BHUSAN NATH 98,MONTALI,MAHISHASAN,KARIMGANJ,ASSAM,788781 9854532604 03-01-2000 29-11-2020 5 Grade IV 102253 LAKHYA JYOTI HAZARIKA JATIN HAZARIKA NH-15,BRAHMAJAN,BRAHMAJAN,BISWANATH,ASSAM,784172 8638045134 26-10-1991 06-12-2020 6 Grade IV 102458 NABAJIT SAIKIA LATE CENIRAM SAIKIA PANIGAON,PANIGAON,PANIGAON,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787052 9127451770 31-12-1994 07-12-2020 7 Grade IV 102516 BABY MISSONG TANKESWAR MISSONG KAITONG,KAITONG ,KAITONG,DHEMAJI,ASSAM,787058 6001247428 04-10-2001 05-12-2020 8 Grade IV 103091 MADHYA MONI SAIKIA BOLURAM SAIKIA Near Gosaipukhuri Namghor,Gosaipukhuri,Adi alengi,Lakhimpur,Assam,787054 8011440485 01-01-1987 07-12-2020 9 Grade IV 103220 JAHAN IDRISH AHMED MUKSHED ALI HAZARIKA K B ROAD,KHUTAKATIA,JAPISAJIA,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 7002409259 01-01-1988 01-12-2020 10 Grade IV 103270 NIHARIKA KALITA ARABINDA KALITA 006,GUWAHATI,KAHILIPARA,KAMRUP -

![[28 DEC. 1989] on the President's 202 Address](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3782/28-dec-1989-on-the-presidents-202-address-33782.webp)

[28 DEC. 1989] on the President's 202 Address

201 Motion of thanks [28 DEC. 1989] on the President's 202 Address SHRI DINESH GOSWAMI: Madam, I THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDE- also beg to lay on the Table a copy each (in PENDENT CHARGE) OF THE MINISTRY English and Hindi, ) of the following papers; OF WATER RESOURCES (SHRI MANOBHAI KOTADIA); Madam, I beg to I. (i) Thirty-first Annual Report and lay on the Table, under sub-section (1) Accounts of the Indian Law Institute, section 619A of tie Companies Act, 1956, a New Delhi, for the year 1987-88, to- copy each (in English and Hindi) of the gether with the Audit Report on the followng papers; — Accounts, (i) Twentieth Annual Report and Accounts (ii) Statement by Government accepting of the Water and Power. Consultancy the above Report. Services (India). Limited, New Delhi, for the year. 1988—89, together with the (iii) Statement giving reasons for the delay Auditor's Report on the Accounts and in laying the paper mentioned at (i) above. the comments of the Comptroller and [Placed in Library. See No. LT— 244/89 Auditor General of India thereon, for (i) to (iii)]. (ii) Review by Government on the II. A copy (in English and Hindi) of working of the Company. the Ministry of Law and Justice (Legisla [Placed in Library. See No. LT— tive Department) Notification S. O. No. 61/89]. 958(E), dated the 17th November, 1989, publishing the Conduct of Election; (Third Amendment) Rules, 1989, under section 169 of the Representation of the REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON People Act, 1951. -

Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014

WID.world WORKING PAPER N° 2019/05 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee Amory Gethin Thomas Piketty March 2019 Growing Cleavages in India? Evidence from the Changing Structure of Electorates, 1962-2014 Abhijit Banerjee, Amory Gethin, Thomas Piketty* January 16, 2019 Abstract This paper combines surveys, election results and social spending data to document the long-run evolution of political cleavages in India. From a dominant- party system featuring the Indian National Congress as the main actor of the mediation of political conflicts, Indian politics have gradually come to include a number of smaller regionalist parties and, more recently, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). These changes coincide with the rise of religious divisions and the persistence of strong caste-based cleavages, while education, income and occupation play little role (controlling for caste) in determining voters’ choices. We find no evidence that India’s new party system has been associated with changes in social policy. While BJP-led states are generally characterized by a smaller social sector, switching to a party representing upper castes or upper classes has no significant effect on social spending. We interpret this as evidence that voters seem to be less driven by straightforward economic interests than by sectarian interests and cultural priorities. In India, as in many Western democracies, political conflicts have become increasingly focused on identity and religious-ethnic conflicts -

(As on 28.05.2020) STATEMENT SHOWING VISITS of MEMBERS of PARLIAMENT (DURING 16TH LOK SABHA) ABROAD and EXPENDITURES on THESE VISITS YEAR-WISE

(As on 28.05.2020) STATEMENT SHOWING VISITS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT (DURING 16TH LOK SABHA) ABROAD AND EXPENDITURES ON THESE VISITS YEAR-WISE Sl. No. Date of Events Events/Country visited Name of Delegates Expenditure as per bills and debit claims settled (Approx.) 2014 1 25-29 June, 2014 Pan-Commonwealth Conference of Commonwealth Women 1. Smt. Meenakashi Lekhi, MP, LS Rs. 14,90,882/- Parliamentarians in London, United Kingdom 2. Ms. Bhavana Pundikrao Gawali, MP, Lok Sabha 2 2-10 October, 2014 The 60th Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference in 1. Shri Pankaj Choudhary, MP, Lok Rs. 16,81,447/- Yaounde, Cameroon Sabha 2. Shri Prem Das Rai, MP, Lok Sabha 3 2-8 November, 2014 The 6th Youth Parliament in North West Provincial Smt. Raksha Nikhil Khadse, MP, Lok Rs. 2,78,000/- Legislature, South Africa Sabha 4 18 – 20 November, Global Financial Crisis workshop for Asia, South East Asia 1. Dr. Kirit Somaiya, MP, Lok Sabha Rs. 1,58,369/- 2014 and India Regions in Dhaka from 18 – 20 November, 2014 2. Smt. V. Sathyabama MP, Lok Sabha 2015 5. 15 – 18 January, Standing Committee Meeting of CSPOC in Jersey in Smt. Sumitra Mahajan, Hon’ble Rs. 55,48,005/- 2015 January, 2015 Speaker, Lok Sabha 6. 4-6 February, 2015 International Parliamentary Conference on Human Rights 1. Shri Prem Prakash Chaudhary, Rs. 9,87,784/- in the Modern Day Commonwealth “Magna Carta to MP, Lok Sabha Commonwealth Charter” in London, 4-6 February, 2015 2. Dr. Satya Pal Singh, MP, Lok Sabha 7. 8 – 10 April, 2015 Workshop on Parliamentary Codes of Conduct-Establishing Shri Kinjarapu Ram Mohan Naidu, Rs. -

Guwahati Development

Editorial Board Advisers: Hrishikesh Goswami, Media Adviser to the Chief Minister, Assam V.K. Pipersenia, IAS, Chief Secretary, Assam Members: L.S. Changsan, IAS, Principal Secretary to the Government of Assam, Home & Political, I&PR, etc. Rajib Prakash Baruah, ACS, Additional Secretary to the Government of Assam, I&PR, etc. Ranjit Gogoi, Director, Information and Public Relations Pranjit Hazarika, Deputy Director, Information and Public Relations Manijyoti Baruah, Sr. Planning and Research Officer, Transformation & Development Department Z.A. Tapadar, Liaison Officer, Directorate of Information and Public Relations Neena Baruah, District Information and Public Relations Officer, Golaghat Antara P.P. Bhattacharjee, PRO, Industries & Commerce Syeda Hasnahana, Liaison Officer, Directorate of Information and Public Relations Photographs: DIPR Assam, UB Photos First Published in Assam, India in 2017 by Government of Assam © Department of Information and Public Relations and Department of Transformation & Development, Government of Assam. All Rights Reserved. Design: Exclusive Advertising Pvt. Ltd., Guwahati Printed at: Assam Government Press 4 First year in service to the people: Dedicated for a vibrant, progressive and resurgent Assam In a democracy, the people's mandate is supreme. A year ago when the people of Assam reposed their faith in us, we were fully conscious of the responsibility placed on us. We acknowledged that our actions must stand up to the people’s expectations and our promise to steer the state to greater heights. Since the formation of the new State Government, we have been striving to bring positive changes in the state's economy and social landscape. Now, on the completion of a year, it makes me feel satisfied that Assam is on a resurgent growth track on all fronts. -

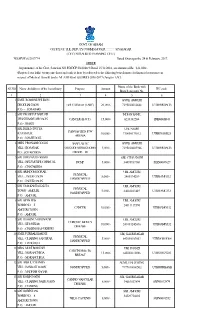

Only Is Here by Released to the Following Beneficiaries for Financial Assistance in Respect of Medical Benefit Under MLAAD Fund (SUHRID) 2016-2017,(Amguri LAC)

GOVT. OF ASSAM OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER ::::::::::: SIVASAGAR ( DECENTRALISED PLANNING CELL) NO.SIV(P) 6/2017/7-9 Dated Sivasagar the 24 th February, 2017. ORDER In pursuance of the Govt. Sanction NO.PD/DCP/50/2016/4 Dated 15/11/2016, an amount of Rs. 4,21,000/- (Rupees Four lakhs twenty one thousand) only is here by released to the following beneficiaries for financial assistance in respect of Medical Benefit under MLAAD Fund (SUHRID) 2016-2017,(Amguri LAC). Name of the Bank with SL NO Name & Address of the beneficiary Purpose Amount IFC code Branch Account No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 SMTI. ROMONI PHUKON AGVB, AMGURI DEODHAI GAON Left CA Breast (LABC) 20,000/- 7195010031648 UTBI0RRBAGB P.O. – JORABARI 2 SRI PROBHAT BARUAH INDIAN BANK, JHANJI BARUAH GAON CANCER (B.O.T.) 15,000/- 6238342204 IDIB000H043 P.O.- JHANJI 3 SRI DEBEN DUTTA UBI, NAMTI PANGASTITIS P/W RATANPUR 10,000/- 730010179812 UTBI0NAMG23 ARENIA P.O. : NAMTI DOLL 4 MISS PRONAMI GOGOI ANAPLASTIC AGVB, AMGURI VILL : BOSAYAK OLIGODENDROGLIOMA 5,000/- 7195010003946 UTBI0RRBAGB PO : SOTAICHIGA GRADE – III 5 SRI HIMA NATH GOGOI SBI, CHAPANANI VILL : BELEMUKHIA DIBRUAL DCMP 5,000/- 34498937168 SBIN0007429 P.O. : CHATAISIGA 6 SRI ARINDOM BORAH UBI, AMGURI PHYSICAL VILL : JALUK GAON 5,000/- 2401134289 UTBI0AMG332 HANDICAPPED P.O. : JALUK GAON 7 SRI UMA KANTA KALITA UBI, AMGURI PHYSICAL TOWN : AMGURI 5,000/- 24010103419 UTBI0AMG332 HANDICAPPED P.O. : AMGURI 8 SRI BIPIN DAS UBI, AMGURI WARD NO – 5 24011119590 CANCER 10,000/- UTBI0AMG332 AMGURI TOWN P.O. : AMGURI 9 SRI HEMONTA KHONIKAR UBI, AMGURI CHRONIC KIDNEY VILL : KHONIKAR 10,000/- 240111242436 UTBI0AMG332 DISEASE P.O. -

Votes, Voters and Voter Lists: the Electoral Rolls in Barak Valley, Assam

SHABNAM SURITA | 83 Votes, Voters and Voter Lists: The Electoral Rolls in Barak Valley, Assam Shabnam Surita Abstract: Electoral rolls, or voter lists, as they are popularly called, are an integral part of the democratic setup of the Indian state. Along with their role in the electoral process, these lists have surfaced in the politics of Assam time and again. Especially since the 1970s, claims of non-citizens becoming enlisted voters, incorrect voter lists and the phenomenon of a ‘clean’ voter list have dominated electoral politics in Assam. The institutional acknowledgement of these issues culminated in the Assam Accord of 1985, establishing the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), a political party founded with the goal of ‘cleaning up’ the electoral rolls ‘polluted with foreign nationals’. Moreo- ver, the Assam Agitation, between 1979 and 1985, changed the public discourse on the validity of electoral rolls and turned the rolls into a major focus of political con- testation; this resulted in new terms of citizenship being set. However, following this shift, a prolonged era of politicisation of these rolls continued which has lasted to this day. Recently, discussions around the electoral rolls have come to popular and academic attention in light of the updating of the National Register of Citizens and the Citizenship Amendment Act. With the updating of the Register, the goal was to achieve a fair register of voters (or citizens) without outsiders. On the other hand, the Act seeks to modify the notion of Indian citizenship with respect to specific reli- gious identities, thereby legitimising exclusion. As of now, both the processes remain on functionally unclear and stagnant grounds, but the process of using electoral rolls as a tool for both electoral gain and the organised exclusion of a section of the pop- ulation continues to haunt popular perceptions. -

Women in Detention and Access to Justice'

10 PARLIAMENT OF INDIA LOK SABHA COMMITTEE ON EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN (2016-2017) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) TENTH REPORT ‘WOMEN IN DETENTION AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE' LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2017/Bhadrapada,1939 (Saka) TENTH REPORT COMMITTEE ON EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN (2016-2017) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) ‘WOMEN IN DETENTION AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE' Presented to Hon’ble Speaker on 30.08.2017 Presented to Lok Sabha on 22.12.2017 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 22.12.2017 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2017/Bhadrapada, 1939 (Saka) E.W.C. No. 101 PRICE: Rs._____ © 2017 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under ……………………………………… CONTENTS Page Nos. Composition of the Committee on Empowerment of Women (2014-2015)...................................................................................................... (iii) Composition of the Committee on Empowerment of Women (2015-2016)...................................................................................................... (iv) Composition of the Committee on Empowerment of Women (2016-2017)...................................................................................................... (v) Introduction....................................................................................................... (vi) REPORT PART I NARRATION ANALYSIS I. Introductory………………………………………………………………..... 1 II. Policing Related Issues…..…………..................................................... 4 III. Overcrowding of Jails..................................…………………………….. 4 IV. The Issue of Undertrails................................…………………………. -

Volume III Issue II Dec2016

MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies MZU JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND CULTURAL STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Volume III Issue 2 ISSN:2348-1188 Editor-in-Chief : Prof. Margaret L. Pachuau Editor : Dr. K.C. Lalthlamuani Editorial Board: Prof. Margaret Ch.Zama Prof. Sarangadhar Baral Dr. Lalrindiki T. Fanai Dr. Cherrie L. Chhangte Dr. Kristina Z. Zama Dr. Th. Dhanajit Singh Advisory Board: Prof.Jharna Sanyal,University of Calcutta Prof.Ranjit Devgoswami,Gauhati University Prof.Desmond Kharmawphlang,NEHU Shillong Prof.B.K.Danta,Tezpur University Prof.R.Thangvunga,Mizoram University Prof.R.L.Thanmawia, Mizoram University Published by the Department of English, Mizoram University. 1 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies 2 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies EDITORIAL It is with great pleasure that I write the editorial of this issue of MZU Journal of Literature and Culture Studies. Initially beginning with an annual publication, a new era unfolds with regards to the procedures and regulations incorporated in the present publication. The second volume to be published this year and within a short period of time, I am fortunate with the overwhelming response in the form of articles received. This issue covers various aspects of the political, social and cultural scenario of the North-East as well as various academic paradigms from across the country and abroad. Starting with The silenced Voices from the Northeast of India which shows women as the worst sufferers in any form of violence, female characters seeking survival are also depicted in Morrison’s, Deshpande’s and Arundhati Roy’s fictions. -

Doers Dreamers Ors Disrupt &

POLITICO.EU DECEMBER 2018 Doers Dreamers THE PEOPLE WHO WILL SHAPE & Disrupt EUROPE IN THE ors COMING YEAR In the waves of change, we find our true drive Q8 is an evolving future proof company in this rapidly changing age. Q8 is growing to become a broad mobility player, by building on its current business to provide sustainable ‘fuel’ and services for all costumers. SOMEONE'S GOT TO TAKE THE LEAD Develop emission-free eTrucks for the future of freight transport. Who else but MAN. Anzeige_230x277_eTrucks_EN_181030.indd 1 31.10.18 10:29 11 CONTENTS No. 1: Matteo Salvini 8 + Where are Christian Lindner didn’t they now? live up to the hype — or did he? 17 The doers 42 In Germany, Has the left finally found its a new divide answer to right-wing nationalism? 49 The dreamers Artwork 74 85 Cover illustration by Simón Prades for POLITICO All illustrated An Italian The portraits African refugees face growing by Paul Ryding for unwelcome resentment in the country’s south disruptors POLITICO 4 POLITICO 28 SPONSORED CONTENT PRESENTED BY WILFRIED MARTENS CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN STUDIES THE EAST-WEST EU MARRIAGE: IT’S NOT TOO LATE TO TALK 2019 EUROPEAN ELECTIONS ARE A CHANCE TO LEARN FROM LESSONS OF THE PAST AND BRING NATIONS CLOSER TOGETHER BY MIKULÁŠ DZURINDA, PRESIDENT, WILFRIED MARTENS CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN STUDIES The East-West relationship is like the cliché between an Eastern bride and a Western man. She is beautiful but poor and with a slightly troubled past. He is rich and comfortable. The West which feels underappreciated and the East, which has the impression of not being heard. -

Lok Sabha Debates

(LJKWK6HULHV9RO;/91R 7KXUVGD\'HFHPEHU $JUDKD\DQD 6DND /2.6$%+$'(%$7(6 (QJOLVK9HUVLRQ 7ZHOIWK 6HVVLRQ (LJKWK/RN6DEKD /2.6$%+$6(&5(7$5,$7 1(:'(/+, 3ULFH5V CONTENTS [Eighth Swiss, Vol. XLV, Twelfth Session, 198811910 (Saka)] No. 23, Thursday, December 15. 1988/Agrahayana 24.1910 (Saka) COLUMNS 'apers Laid on the Table 8-12 Public Accounts Committee- 13 Hundred and Fortieth Report- presented Petition Re: Privatisation of 13 B.E.L. - Taloja unit Matters Under Rule 377 - 13-21 (i) Need to direct the Government of Rajasthan 13-14 to ensure proper representation in jobs to backward classes - Shn Shankar Lal (ii) Need to sanction construction of a bridge over 14 river Sikarhana in Bihar in the next year's plan- Shrimati Prabhawati Gupta (iii) Need to check the spread of heart ailments, particularly 15 amongst the youth in the country - Dr. Chandra Shekhar Trlpathi (iv) Steps needed to encourage the use of Hindi and 15-16 other regionallanguaes - Silri Madan Pandey (v) Need to give clearance to the cotton procurement 16-17 scheme submitted by the Government of Maharashtra and also to ensure remunerative price for cotton - Shrimati Usha Choudhari (vi) Demand for revision of rate of royalty on oil to 18 Assam- Shri Dinesh Goswami (ii) COLUMNS (vii) Need to remove the disparity in the levy price 1S-19 of sugar- Shri Ram Narain Singh (viii) Need to review the decision to discontinue the 19-20 Central Investment subsidy to non-manufacturing units- Shri G.M. Banatwalla (ix) Need to augment railway facilities in Bilaspur 20-21 (Madhya Pradesh)- Dr. -

Human Rights Monitoring Report

Human Rights Monitoring Report 1 – 31 May 2018 1 June 2018 1 Odhikar has, since 1994, been monitoring the human rights situation in Bangladesh in order to promote and protect civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of Bangladeshi citizens and to report on violations and defend the victims. Odhikar does not believe that the human rights movement merely endeavours to protect the „individual‟ from violations perpetrated by the state; rather, it believes that the movement to establish the rights and dignity of every individual is part of the struggle to constitute Bangladesh as a democratic state. Odhikar has always been consistent in creating mass awareness of human rights issues using several means, including reporting violations perpetrated by the State and advocacy and campaign to ensure internationally recognised civil and political rights of citizens. The Organisation unconditionally stands by the victims of oppression and maintains no prejudice with regard to political leanings or ideological orientation, race, religion or sex. In line with this campaign, Odhikar prepares and releases human rights status reports every month. The Organisation has prepared and disseminated this human rights monitoring report of May 2018, despite facing persecution and continuous harassment and threats to its existence since 2013. Although many incidents of human rights violations occur every month, only a few significant incidents have been highlighted in this report. Information used in the report was gathered by grassroots human rights