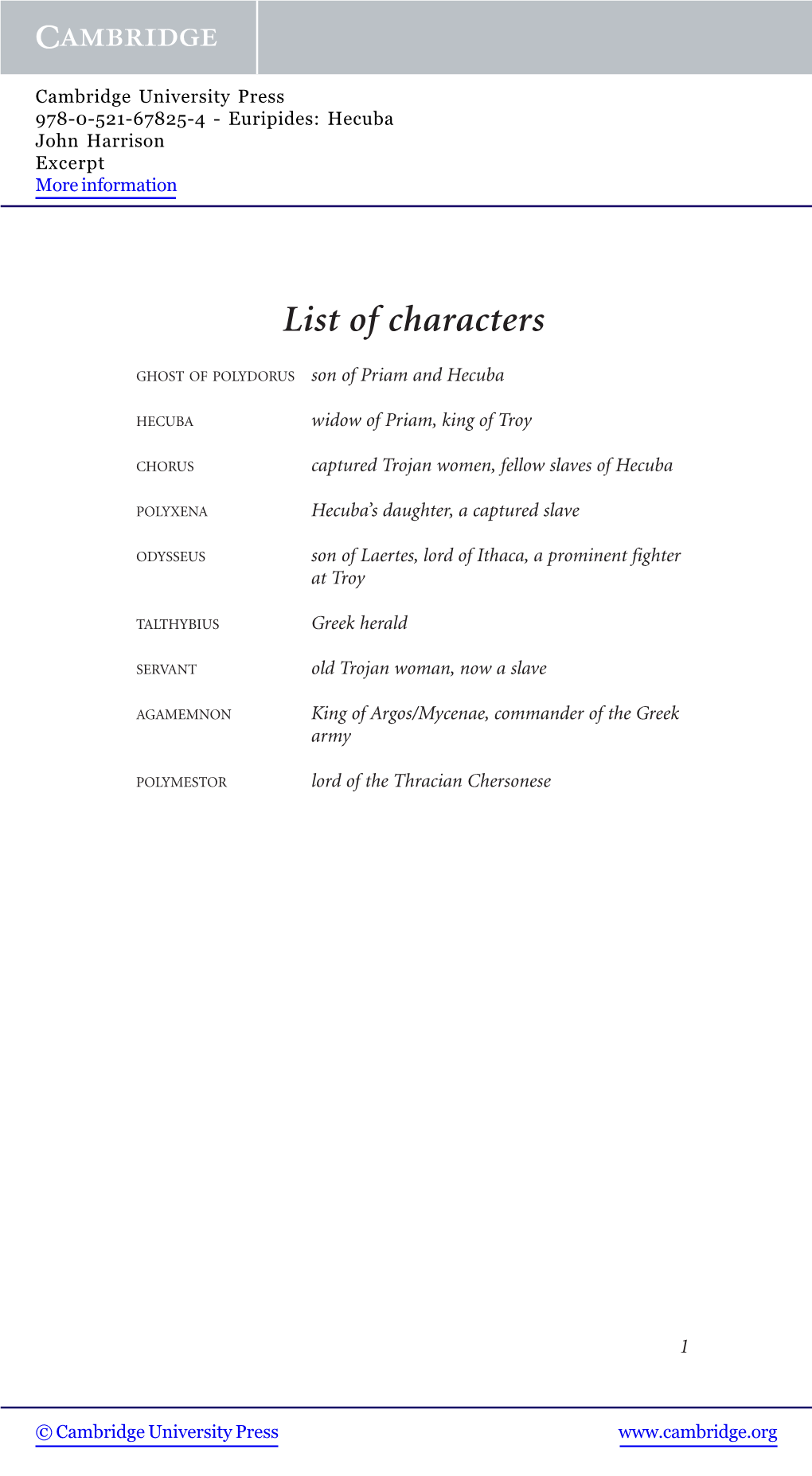

List of Characters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trojan Women: Introduction

Trojan Women: Introduction 1. Gods in the Trojan Women Two gods take the stage in the prologue to Trojan Women. Are these gods real or abstract? In the prologue, with its monologue by Poseidon followed by a dialogue between the master of the sea and Athena, we see them as real, as actors (perhaps statelier than us, and accoutered with their traditional props, a trident for the sea god, a helmet for Zeus’ daughter). They are otherwise quite ordinary people with their loves and hates and with their infernal flexibility whether moral or emotional. They keep their emotional side removed from humans, distance which will soon become physical. Poseidon cannot stay in Troy, because the citizens don’t worship him any longer. He may feel sadness or regret, but not mourning for the people who once worshiped but now are dead or soon to be dispersed. He is not present for the destruction of the towers that signal his final absence and the diaspora of his Phrygians. He takes pride in the building of the walls, perfected by the use of mason’s rules. After the divine departures, the play proceeds to the inanition of his and Apollo’s labor, with one more use for the towers before they are wiped from the face of the earth. Nothing will be left. It is true, as Hecuba claims, her last vestige of pride, the name of Troy remains, but the place wandered about throughout antiquity and into the modern age. At the end of his monologue Poseidon can still say farewell to the towers. -

Ovid Book 12.30110457.Pdf

METAMORPHOSES GLOSSARY AND INDEX The index that appeared in the print version of this title was intentionally removed from the eBook. Please use the search function on your eReading device to search for terms of interest. For your reference, the terms that ap- pear in the print index are listed below. SINCE THIS index is not intended as a complete mythological dictionary, the explanations given here include only important information not readily available in the text itself. Names in parentheses are alternative Latin names, unless they are preceded by the abbreviation Gr.; Gr. indi- cates the name of the corresponding Greek divinity. The index includes cross-references for all alternative names. ACHAMENIDES. Former follower of Ulysses, rescued by Aeneas ACHELOUS. River god; rival of Hercules for the hand of Deianira ACHILLES. Greek hero of the Trojan War ACIS. Rival of the Cyclops, Polyphemus, for the hand of Galatea ACMON. Follower of Diomedes ACOETES. A faithful devotee of Bacchus ACTAEON ADONIS. Son of Myrrha, by her father Cinyras; loved by Venus AEACUS. King of Aegina; after death he became one of the three judges of the dead in the lower world AEGEUS. King of Athens; father of Theseus AENEAS. Trojan warrior; son of Anchises and Venus; sea-faring survivor of the Trojan War, he eventually landed in Latium, helped found Rome AESACUS. Son of Priam and a nymph AESCULAPIUS (Gr. Asclepius). God of medicine and healing; son of Apollo AESON. Father of Jason; made young again by Medea AGAMEMNON. King of Mycenae; commander-in-chief of the Greek forces in the Trojan War AGLAUROS AJAX. -

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

Extended Abstract Vol 3, Iss 1 International Journal of Advanced

Extended Abstract International Journal of Advanced Research in Electrical, Electronics and Vol 3, Iss 1 Instrumentation Engineering 2020 Machine Learning 2019: Cassandra-A novel versatile fully scalable Predictive Maintenance solution: Ludovic A. Krundel - IngDan Labs • Cogobuy Group, Comtech Tower, Hong Kong Ludovic A. Krundel IngDan Labs, Cogobuy Group, Comtech Tower, Hong Kong Machines with moving parts induce vibrations. Paris, who demands that he will travel to Sparta, and Various readings such as wavelength, frequency, on the off chance that Hesione isn't returned to him, he phase, amplitude, and more, measure these vibrations. will take Helen. The pressure increments when Analysis of these readings can not only identify but Cassandra encounters a sort of fit and collapses, also facilitate the prediction of faults. Advanced having anticipated the drop of Troy. By the time she calculations such as Fast Fourier Transform and recuperates, Paris has cruised to Sparta and returned, application of pre-trained deep networks lead to bringing Helen, who wears a veil. Cassandra before projection estimates. long starts to suspect—but does not need to believe— that Helen isn't in Troy, after all. No one is allowed to Cassandra provides accurate Predictive Maintenance see her, and Cassandra has seen Paris' previous darling for all types of machinery with moving parts and more Oenone clearing out his room. Be that as it may, she is such as train rails. Our solution is as revolutionary as incapable to acknowledge that Troy—that her father— replacing the horse by the car: using Cassandra in a would proceed to get ready for a war on the off chance factory can avoid considerable costs in the break down that its preface were untrue.In spite of the fact that related expenses. -

Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation Jonathan Cornil Scriptie voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Master in de Taal- en letterkunde (Latijn – Engels) 2011-2012 Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Verbaal ii Table of Contents Table of Contents iii Foreword v Introduction vii Chapter I. De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological and Historical Comments 1 A. Dares and His Historia: Shrouded in Mystery 2 1. Who Was ‘Dares the Phrygian’? 2 2. The Role of Cornelius Nepos 6 3. Time of Origin and Literary Environment 9 4. Analysing the Formal Characteristics 11 B. Dares as an Example of ‘Rewriting’ 15 1. Homeric Criticism and the Trojan Legacy in the Middle Ages 15 2. Dares’ Problematic Connection with Dictys Cretensis 20 3. Comments on the ‘Lost Greek Original’ 27 4. Conclusion 31 Chapter II. Translations 33 A. Translating Dares: Frustra Laborat, Qui Omnibus Placere Studet 34 1. Investigating DETH’s Style 34 2. My Own Translations: a Brief Comparison 39 3. A Concise Analysis of R.M. Frazer’s Translation 42 B. Translation I 50 C. Translation II 73 D. Notes 94 Bibliography 95 Appendix: the Latin DETH 99 iii iv Foreword About two years ago, I happened to be researching Cornelius Nepos’ biography of Miltiades as part of an assignment for a class devoted to the study of translating Greek and Latin texts. After heaping together everything I could find about him in the library, I came to the conclusion that I still needed more information. So I decided to embrace my identity as a loyal member of the ‘Internet generation’ and began my virtual journey through the World Wide Web in search of articles on Nepos. -

The Sacrifice of Polyxena

The Sacrifice of Polyxena Melissa Natividade The Sacrifice of Polyxena By Charles Le Brun 1619–1690 Paris Date: 1647 Accession Number: 2013.183 Much has been discussed in great detail throughout this semester but naturally much more happened during the Trojan War than can be discussed in the three hours of class each week. Polyxena is one of those subjects that was touched upon but never truly explored in detail, making the painting recounting her sacrifice at the Metropolitan Museum of Art quite surprising and intriguing. Though there are discrepancies regarding details in the setup of the painting, The Sacrifice of Polyxena by Charles Le Brun successfully used specific iconography to capture and reconstruct the exact moment in the Trojan War that he wished to portray to his audience. At first glance, it was clear that the painting was a sacrifice of a young woman, leaving little room for debate on the possible identity of the subject of the painting. With minimal knowledge of the Trojan War, the subject of the sacrifice could be narrowed down to either the sacrifice of Iphigenia at Aulis or the sacrifice of Polyxena at Troy. One object, Achilles’ tomb, in the background of the painting immediately clarifies the circumstance as being the sacrifice of Polyxena. Achilles was the only great warrior that would have gotten such a proper burial and though that did not happen in the Homer’s original works, Le Brun represents Achilles’ tomb as being quite grand to invoke Achilles’ presence in the situation despite his physical absence. Other characters specific to this scene in Ovid’s “Metamorphoses” are Hecuba and Neoptolemus, who has substantial iconography in the painting. -

Breaking the Silence of Homer's Women in Pat Barker's the Silence

International Journal of English Language Studies (IJELS) ISSN: 2707-7578 DOI: 10.32996/ijels Website: https://al-kindipublisher.com/index.php/ijels Breaking the Silence of Homer’s Women in Pat Barker’s the Silence of The Girls Indrani A. Borgohain Ph.D. Candidate, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan Corresponding Author: Indrani A. Borgohain, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: December 25, 2020 Since time immemorial, women have been silenced by patriarchal societies in most, if Accepted: February 10, 2021 not all, cultures. Women voices are ignored, belittled, mocked, interrupted or shouted Volume: 3 down. The aim of this study examines how the contemporary writer Pat Barker breaks Issue: 2 the silence of Homer’s women in her novel The Silence of The Girl (2018). A semantic DOI: 10.32996/ijels.2021.3.2.2 interplay will be conducted with the themes in an attempt to show how Pat Barker’s novel fit into the Greek context of the Trojan War. The Trojan War begins with the KEYWORDS conflict between the kingdoms of Troy and Mycenaean Greece. Homer’s The Iliad, a popular story in the mythological of ancient Greece, gives us the story from the The Iliad, Intertextuality, perspective of the Greeks, whereas Pat Barker’s new novel gives us the story from the Adaptation, palimpsestic, Trojan perspective of the queen- turned slave Briseis. Pat Barker’s, The Silence of the Girls, War, patriarchy, feminism written in 2018, readdresses The Iliad to uncover the unvoiced tale of Achilles’ captive, who is none other than Briseis. In the Greek saga, Briseis is the wife of King Mynes of Lyrnessus, an ally of Troy. -

Curriculum Back Up

Thucydides and Euripides: The Changing Civic and Moral Values during the Peloponnesian War Mary Ann T. Natunewicz INTRODUCTION This unit is part of a two-semester course taken by tenth graders in the second half of the school year. The course is team-taught by an art teacher and by a language teacher, with one nine-week semester devoted to art and the other nine-week semester to Greek literature, mythology and history. The school is on an accelerated block schedule and the class meets every day for 90 minutes. Smaller sections of this unit could be used in the Ancient History part of a World History course or a literature course that included Greek tragedy. The unit described below is in the literature semester of the course. It has been preceded by a three-week unit on Greek mythology. It will be followed by two weeks spent reading other Greek drama. The approximate length of the unit is four weeks. DISCUSSION OF THE UNIT One of the most fascinating periods that can be studied is fifth century B.C. Greece. So much was happening–painting and sculpture were flowering, scientists and philosophers were speculating on the nature of the universe, playwrights vied with one another in the dramatic contests, storytellers and poets were in demand, citizens were actively involved in running many states and historians were grappling with the significance of both ancient and current events. But what happens when a world war envelops this flourishing culture? What changes occur in individuals and in states? The general aim of this curriculum is to examine the view of late fifth century B.C. -

TRAUMA in EURIPIDES' HECUBA by Julia E. Paré

Falling on Deaf Ears: Trauma in Euripides' Hecuba Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Pare, Julia Elizabeth Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 16:07:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/641676 FALLING ON DEAF EARS: TRAUMA IN EURIPIDES’ HECUBA by Julia E. Paré ____________________________ Copyright © Julia Paré 2020 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AND CLASSICS In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN CLASSICS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Julia E. Paré, titled “Falling on Deaf Ears: Trauma in Euripides’ Hecuba,” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Master’s Degree. _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________May 25, 2020 David Christenson _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________May 25, 2020 Courtney Friesen _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________May 25, 2020 Arum Park Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Master’s requirement. -

Female Characters, Female Sympathetic Choruses, and the “Suppression” of Antiphonal Lament at the Openings of Euripides’ Phaethon, Andromeda, and Hypsipyle*

FRAMMENTI SULLA SCENA (ONLINE) Studi sul dramma antico frammentario Università deGli Studi di Torino Centro Studi sul Teatro Classico http://www.ojs.unito.it/index.php/fss www.teatroclassico.unito.it ISSN 2612-3908 1 • 2020 FEMALE CHARACTERS, FEMALE SYMPATHETIC CHORUSES, AND THE “SUPPRESSION” OF ANTIPHONAL LAMENT AT THE OPENINGS OF EURIPIDES’ PHAETHON, ANDROMEDA, AND HYPSIPYLE* VASILIKI KOUSOULINI NATIONAL AND KAPODISTRIAN UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS [email protected] Female choruses abound in Euripides’ plays.1 While there are many in his extant plays, we also encounter choruses of women in his fragmentary ones.2 Little attention has been paid to the existence of sympathetic female choruses in Euripides’ fragmentary dramas and their in- teraction with female characters. A sympathetic female chorus seems to appear in conjunction with a female character in many Euripidean fragmentary plays. The chorus of the Alexander in * This research is co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Social Fund- ESF) through the Opera- tional ProGramme «Human Resources Development, Education and LifelonG LearninG» in the context of the pro- ject “Reinforcement of Postdoctoral Researchers - 2nd Cycle” (MIS-5033021), implemented by the State Scholar- ships Foundation (ΙΚΥ). 1 There is a female chorus in Euripides’ Medea, Hippolytus, Andromache, Hecuba, Suppliant Women, Ion, Electra, Trojan Women, Iphigenia among the Taurians, Helen, Phoenician Women, Orestes, Iphigenia in Aulis, and Bacchae. Mastronarde observed that there are 15 male choruses, 62 female choruses, and 105 choruses with undetermined gender in Euripides’ corpus. Cf. MASTRONARDE 2010, 103. AccordinG to Calame, the 82% of Euripides’ traGic choruses con- sists of women. Cf. CALAME 2020, 776. -

Falling on Deaf Ears: Traumatic Loss of Language in Euripides' Hecuba Recent Scholarship Has Detailed the Rhetorical Prowess O

Falling on Deaf Ears: Traumatic Loss of Language in Euripides’ Hecuba Recent scholarship has detailed the rhetorical prowess of Euripides’ Hecuba, whose agones in the eponymous tragedy should show her rightfully victorious, but ultimately result in her defeat in two of three contests (Kastely 1993). Her progressive response to her declining fortunes has been characterized as a “moral decline,” reflected in the argumentative shift in her agon with Agamemnon to include his attachment to Cassandra and subsequent murder of Polymestor’s children (Lloyd 1992). However, Hecuba’s limited success with rhetoric and eventual replacement of words by violent action are better characterized as a physical expression and manifestation of trauma consistent with Cathy Caruth’s description of traumatic narratives as “a kind of double telling, the oscillation between a crisis of death and the correlative crisis of life: between the story of the unbearable nature of an event and the story of the unbearable nature of its survival” (Caruth 1996). In this paper, I argue that the Hecuba dramatizes externally Hecuba’s traumatic narrative in her shift from speech to violent action. Her lack of success rhetorically is not only the result of her victimhood, but a byproduct of how trauma renders narratives incommunicable to those outside of its effects. Hecuba is the “embodiment of Trojan suffering” and a consistent presence on stage throughout the play, which establishes all dramatic action in relation to her character (Lloyd 94, 1992). In her agones with Odysseus and Agamemnon, she relives her wartime experiences in an attempt to engender empathy for herself. In Odysseus’ case, she recalls how she spared him when he came, disguised, to Troy. -

Nick Susa Epic Mythomemology – the Iliad Book 1: Achilles Was Fighting

Nick Susa Epic Mythomemology – The Iliad Book 1: Achilles was fighting alongside Agamemnon, the King of Argos, during the Trojan war. After winning a battle each was given a war prize, a woman. Achilles was given Briseis, and Agamemnon was given Chryseis. However, the father of Chryseis, Chryses, who was also a priest of Apollo, wasn’t ready to part with his daughter and came with a ransom for his daughter for King Agamemnon. Agamemnon refused the ransom in favor of keeping Chryseis and threatened the priest. Horrified and upset the priest (Chryses) calls upon Apollo and asks him to put a plague upon the Achaean armies, one of which Agamemnon leads. For nine days the armies were struck with a plague, on the tenth Achilles called a meeting to find the reason for the plague. Calchas, a prophet and follower of Apollo, being protected by Achilles, explains that Agamemnon refusing the ransom was the reason for the plague and he must return the girl and make a sacrifice of one hundred cows to Apollo in order to end the plague. Agamemnon decides to appease Apollo, but only if he can take away Achilles war prize, Briseis. Achilles doesn’t believe that Agamemnon should gain Briseis, so the two begin to argue. Achilles decides that he and his men shall not fight in the war because of Agamemnon’s actions. After Agamemnon takes Briseis away, Achilles cries and prays to his mother, Thetis, asking her to have Zeus grant the Achaean armies many loses. Zeus was not around to be asked though, but after twelve days, he returns and promises to Thetis that he will grant the Trojans many victories and the Achaeans many losses.