Flourishing As the Standard for Evaluating the Social Practice of Competitive Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Neo-Caliphate of the “Islamic State”

CSS Analyses in Security Policy CSS ETH Zurich N0. 166, December 2014, Editor: Christian Nünlist The Neo-Caliphate of the “Islamic State” The so-called “Islamic State” represents a new phase in global jihad, wherein efforts will be made to seize and retain territorial control in the face of overwhelming Western military superiority. While this potentially makes jihadist groups vulnerable to destruction, it also increases the risk of home-grown radicalization as foreign fighters flock to join the new “Caliphate”. By Prem Mahadevan The jihadist takeover of Iraq’s second-larg- est city Mosul in June 2014 sharply focused international attention on the country. Coming at a time when Western policy concerns were oriented towards Ukraine, the South China Sea, Gaza, and Afghani- stan, the takeover’s abruptness came as a surprise. Shortly thereafter, the responsible jihadist group named itself the “Islamic State” (IS) and declared the formation of a new Caliphate, signaling that its ideologi- cal agenda was not confined to distinct po- litical or geographic boundaries. The IS has been since projecting itself as a rival to al- Qaida, by competing for credibility and le- gitimacy among the global jihadist com- munity. The IS is unusual in that, until very recent- ly, it had a record of impressive operational A militant Islamist fighter celebrates the declaration of an Islamic “caliphate” in Syria’s northern success, combined with a slick propaganda Raqqa province in June 2014. Reuters machinery to showcase this success. In contrast, al-Qaida remains weakened as a result of counterterrorism efforts in the Af- ghanistan-Pakistan region. -

Vision Performance Institute

Vision Performance Institute Technical Report Individual character legibility James E. Sheedy, OD, PhD Yu-Chi Tai, PhD John Hayes, PhD The purpose of this study was to investigate the factors that influence the legibility of individual characters. Previous work in our lab [2], including the first study in this sequence, has studied the relative legibility of fonts with different anti- aliasing techniques or other presentation medias, such as paper. These studies have tested the relative legibility of a set of characters configured with the tested conditions. However the relative legibility of individual characters within the character set has not been studied. While many factors seem to affect the legibility of a character (e.g., character typeface, character size, image contrast, character rendering, the type of presentation media, the amount of text presented, viewing distance, etc.), it is not clear what makes a character more legible when presenting in one way than in another. In addition, the importance of those different factors to the legibility of one character may not be held when the same set of factors was presented in another character. Some characters may be more legible in one typeface and others more legible in another typeface. What are the character features that affect legibility? For example, some characters have wider openings (e.g., the opening of “c” in Calibri is wider than the character “c” in Helvetica); some letter g’s have double bowls while some have single (e.g., “g” in Batang vs. “g” in Verdana); some have longer ascenders or descenders (e.g., “b” in Constantia vs. -

The Yubikey Manual

The YubiKey Manual Usage, configuration and introduction of basic concepts Version: 3.4 Date: 27 March, 2015 The YubiKey Manual Disclaimer The contents of this document are subject to revision without notice due to continued progress in methodology, design, and manufacturing. Yubico shall have no liability for any error or damages of any kind resulting from the use of this document. The Yubico Software referenced in this document is licensed to you under the terms and conditions accompanying the software or as otherwise agreed between you or the company that you are representing. Trademarks Yubico and YubiKey are trademarks of Yubico AB. Contact Information Yubico AB Kungsgatan 37, 8 floor 111 56 Stockholm Sweden [email protected] © Yubico, 2015 Page 2 of 40 Version: Yubikey Manual 3.4 The YubiKey Manual Contents 1 Document Information 1.1 Purpose 1.2 Audience 1.3 Related documentation 1.4 Document History 1.5 Definitions 2 Introduction and basic concepts 2.1 Basic concepts and terms 2.2 Functional blocks 2.3 Security rationale 2.4 OATH-HOTP mode 2.5 Challenge-response mode 2.6 YubiKey NEO 2.7 YubiKey versions and parametric data 2.8 YubiKey Nano 3 Installing the YubiKey 3.1 Inserting the YubiKey for the first time (Windows XP) 3.2 Verifying the installation (Windows XP) 3.3 Installing the key under Mac OS X 3.4 Installing the YubiKey on other platforms 3.5 Understanding the LED indicator 3.6 Testing the installation 3.7 Installation troubleshooting 4 Using the YubiKey 4.1 Using multiple configurations (from version 2.0) 4.2 Updating a -

Exploring the Interconnectedness of Cryptocurrencies Using Correlation Networks

Exploring the Interconnectedness of Cryptocurrencies using Correlation Networks Andrew Burnie UCL Computer Science Doctoral Student at The Alan Turing Institute [email protected] Conference Paper presented at The Cryptocurrency Research Conference 2018, 24 May 2018, Anglia Ruskin University Lord Ashcroft International Business School Centre for Financial Research, Cambridge, UK. Abstract Correlation networks were used to detect characteristics which, although fixed over time, have an important influence on the evolution of prices over time. Potentially important features were identified using the websites and whitepapers of cryptocurrencies with the largest userbases. These were assessed using two datasets to enhance robustness: one with fourteen cryptocurrencies beginning from 9 November 2017, and a subset with nine cryptocurrencies starting 9 September 2016, both ending 6 March 2018. Separately analysing the subset of cryptocurrencies raised the number of data points from 115 to 537, and improved robustness to changes in relationships over time. Excluding USD Tether, the results showed a positive association between different cryptocurrencies that was statistically significant. Robust, strong positive associations were observed for six cryptocurrencies where one was a fork of the other; Bitcoin / Bitcoin Cash was an exception. There was evidence for the existence of a group of cryptocurrencies particularly associated with Cardano, and a separate group correlated with Ethereum. The data was not consistent with a token’s functionality or creation mechanism being the dominant determinants of the evolution of prices over time but did suggest that factors other than speculation contributed to the price. Keywords: Correlation Networks; Interconnectedness; Contagion; Speculation 1 1. Introduction The year 2017 saw the start of a rapid diversification in cryptocurrencies. -

From Function to Flourishing: Neo-Aristotelian Ethics and the Science of Life

From Function to Flourishing: Neo-Aristotelian Ethics and the Science of Life by Seyedeh Parisa Moosavi Tabatabaei A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Toronto © Copyright 2019 by Seyedeh Parisa Moosavi Tabatabaei From Function to Flourishing: Neo-Aristotelian Ethics and the Science of Life Parisa Moosavi Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Toronto 2019 Abstract Neo-Aristotelian ethical naturalism purports to place moral virtue in the natural world by showing that it is an instance of natural goodness—a kind of goodness supposedly also found in the biological realm of plants and non-human animals. One of the central issues facing this metaethical view concerns its commitment to a teleological conception of the nature of life that seems radically out of touch with the understanding of life in modern biology. In this dissertation, I aim to mend the relationship between neo-Aristotelian ethics and the science of biology by way of three contributions: First, I argue that contrary to what many contemporary neo-Aristotelians have claimed, the science of biology is relevant to assessing central commitments of neo-Aristotelian naturalism regarding the domain of life. Second, I provide new foundations for neo-Aristotelian naturalism by engaging recent and unexplored work in philosophy of biology on theories of function and the nature of living organisms. Lastly, I develop and defend a novel account of the neo-Aristotelian concept of natural goodness that is distinctive for incorporating our scientific understanding of the nature of life. ii Acknowledgments I owe the deepest debt of gratitude to Sergio Tenenbaum and Denis Walsh, whose supervision and support was crucial for the completion of this dissertation. -

P2P Electricity Transaction Between Ders by Blockchain Technology

DEGREE PROJECT IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING, SECOND CYCLE, 30 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2018 P2P Electricity transaction between DERs by Blockchain Technology RUOGU LI KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE KTH Royal Institute of Technology School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Master’s Thesis in Computer Science and Computer Engineering P2P Electricity transaction between DERs by Blockchain Technology Author: Ruogu Liu Supervisors: Anne Håkansson Xue Wang Examiner: Prof.Mihhail Matskin, KTH, Sweden ii Abstract The popularity of blockchain technologies increases with a significant rise in the price of cryptocurrency in 2017, which drew much attention in the academia and industry to research and implement new application or new blockchain technology. Many new blockchains have emerged over the last year in a broad spectrum of sectors and use cases including IOT, Energy, Finance, Real estate, Entertainment, etc. Despite many exciting research and applications have been done, there are still many areas worth investigating, and implementation of the blockchain based distributed application are still facing much uncertainty and challenging since blockchain is still an emerging technology. Meanwhile, the energy sector is under a transition to be digitalized and more distributed. A global technology revolution has disrupted the conventional centralized power system with distributed resources and technologies, like photovoltaic units (PV), batteries, electric mobilities, etc. The citizens then have control of their generation and consumption profiles. The purpose of this master thesis is to explore existing blockchain technology, and smart contracts such as IOTA, NEO, Ethereum Tobalaba, which can be adapted in the energy sector. Within this thesis, blockchain and the smart contract is proposed as a way of building distributed applications for a p2p transaction use case in the energy asset management platform. -

Qualitative Comparative Analysis

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/2531-0488.htm Qualitative Qualitative comparative analysis: comparative justifying a neo-configurational analysis approach in management research Tobias Coutinho Parente 399 Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil and Instituto Brasileiro de Governança Corporativa – IBGC, São Paulo, Brazil, and Received 10 May 2019 Revised 22 July 2019 Ryan Federo Accepted 7 August 2019 ESADE Business School, Barcelona, Spain Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to critically reflect and offer insights on how to justify the use of qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) as a research method for understanding the complexity of organizational phenomena, by applying the principles of the neo-configurational approach. Design/methodology/approach – We present and critically examine three arguments regarding the use of QCA for management research. First, they discuss the need to assume configurational theories to build and empirically test a causal model of interest. Second, we explain how the three principles of causal complexity are assumed during the process of conducting QCA-based studies. Third, we elaborate on the importance of case knowledge when selecting the data for the analysis and when interpreting the results. Findings – We argue that it is important to reflect on these arguments to have an appropriate research design. In the true spirit of the configurational approach, we contend that the three arguments presented are necessary; however, each argument is insufficient to warrant a QCA research design. Originality/value – This paper contributes to management research by offering key arguments on how to justify the use of QCA-based studies in future research endeavors. -

Uncorrected Proof

AUTHOR'S PROOF JrnlID 13423_ArtID 229_Proof# 1 - 11/02/2012 Psychon Bull Rev DOI 10.3758/s13423-012-0229-7 1 3 BRIEF REPORT 2 4 The QWERTY Effect: How typing shapes the meanings 5 of words. 6 Kyle Jasmin & Daniel Casasanto 7 8 # The Author(s) 2012. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com 9 10 Abstract The QWERTY keyboard mediates communication in valence, on average, than words with more left-side letters: 22 11 for millions of language users. Here, we investigated whether the QWERTY effect. This effect was strongest in new words 23 12 differences in the way words are typed correspond to differ- coined after QWERTY was invented and was also found in 24 13 ences in their meanings. Some words are spelled with more pseudowords. Although these data are correlational, the dis- 25 14 letters on the right side of the keyboard and others with more covery of a similar pattern across languages, which was stron- 26 15 letters on the left. In three experiments, we tested whether gest in neologisms, suggests that the QWERTY keyboard is 27 16 asymmetries in the way people interact with keys on the right shaping the meanings of words as people filter language 28 17 and left of the keyboard influence their evaluations of the through their fingers. Widespread typing introduces a new 29 18 emotional valence of the words. We found the predicted mechanism by which semantic changes in language can arise. 30 19 relationship between emotional valence and QWERTY key 20 position across three languages (English, Spanish, and Dutch). -

An Improved Arabic Keyboard Layout

Sci.Int.(Lahore),33(1),5-15,2021 ISSN 1013-5316; CODEN: SINTE 8 5 AN IMPROVED ARABIC KEYBOARD LAYOUT 1Amjad Qtaish, 2Jalawi Alshudukhi, 3Badiea Alshaibani, 4Yosef Saleh, 5Salam Bazrawi College of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Ha'il, Ha'il, Saudi Arabia. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT: One of the most important human–machine interaction (HMI) systems is the computer keyboard. The keyboard layout (KL) dictates how a person interacts with a physical keyboard through the way in which the letters, numbers, punctuation marks, and symbols are mapped and arranged on the keyboard. Mapping letters onto the keys of a keyboard is complex because many issues need to be taken into considerations, such as the nature of the language, finger fatigue, hand balance, typing speed, and distance traveled by fingers during typing and finger movements. There are two main kinds of KL: English and Arabic. Although numerous research studies have proposed different layouts for the English keyboard, there is a lack of research studies that focus on the Arabic KL. To address this lack, this study analyzed and clarified the limitations of the standard legacy Arabic KL. Then an efficient Arabic KL was proposed to overcome the limitations of the current KL. The frequency of Arabic letters and bi-gram probabilities were measured on a large Arabic corpus in order to assess the current KL and to design the improved Arabic KL. The improved Arabic KL was then evaluated and compared against the current KL in terms of letter frequency, finger-travel distance, hand and finger balance, bi-gram frequency, row distribution, and most frequent words. -

French Foreign Policy in Africa: Between Pré Carré and Multilateralism

FRENCH FOREIGN POLICY IN AFRICA: BETWEEN PRÉ CARRÉ AND MULTILATERALISM Sylvain Touati An Africa Programme Briefing Note February 2007 Chatham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author. © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. 2 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Historical Context 2 3 Public Aid for Development 5 4 Political Trends 9 5 International Competition 14 6 France in Europe 16 7 2007 Elections 18 8 Conclusions 21 3 1 INTRODUCTION “Africa is a real opportunity for France. It broadens both our horizon and our ambition on the international scene. It is true in the diplomatic, economic and cultural context.” Dominique de Villepin, 18 June 20031 France’s monopoly of Africa is under threat. The last 50 years have seen the French battling to hold on to the ‘privileged relationship’ with their former colonial empire, and a number of factors have forced the once imperial power into redefining its affiliation with ex-colonies, such as new laws on aid distribution, the integration of the EU and modern economic reforms. In the post-Cold War era, ‘multilateralism’ has become the latest political buzzword, and in its wake a notable shift in French policy in Africa has emerged. -

Illicit Financial Flows in Africa

POLICY BRIEF Illicit financial flows in Africa Drivers, destinations, and policy options Landry Signé, Mariama Sow, and Payce Madden March 2020 Abstract Since 1980, an estimated $1.3 trillion has left sub-Saharan Africa in the form of illicit financial flows (per Global Financial Integrity methodology), posing a central challenge to development financing. In this paper, we provide an up-to-date examination of illicit financial flows from Africa from 1980 to 2018, assess the drivers and destinations of illicit outflows, and examine policy options to reduce them. Using trade misinvoicing and balance-of-payments discrepancies to estimate illicit financial flows, we find higher real GDP is associated with higher illicit financial flows due to the increased opportunities to channel illicit resources abroad generated by higher economic activity, suggesting a need for increased diligence as countries grow. We also find that higher taxes and higher inflation lead to higher illicit financial outflows, suggesting that firms seek out relatively more stable or favorable fiscal environments for their funds. We further find that, over the past decade, there has been an increase in illicit outflows of capital toward emerging and developing economies (e.g., China) as trade between Africa and these countries has increased. We conclude with policy recommendations to address illicit financial flows in order to shift the discussion toward effective policies applicable to all countries. Illicit financial flows in Africa: Drivers, destinations, and policy options AFRICA GROWTH INITIATIVE 1. INTRODUCTION While the international development community often focuses on the amount of aid and investment that enters the African continent, the other part of the balance sheet—the funds exiting the continent—has often been overlooked. -

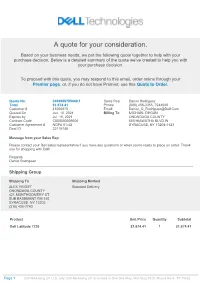

Dell Latitude 7220 I5

A quote for your consideration. Based on your business needs, we put the following quote together to help with your purchase decision. Below is a detailed summary of the quote we’ve created to help you with your purchase decision. To proceed with this quote, you may respond to this email, order online through your Premier page, or, if you do not have Premier, use this Quote to Order. Quote No. 3000088785049.1 Sales Rep Daniel Rodriguez Total $1,874.41 Phone (800) 456-3355, 7244648 Customer # 41069979 Email [email protected] Quoted On Jun. 16, 2021 Billing To MICHAEL DEGAN Expires by Jul. 16, 2021 ONONDAGA COUNTY Contract Code C000000005600 650 HIAWATHA BLVD W Customer Agreement # NCPA 01-42 SYRACUSE, NY 13204-1123 Deal ID 22119748 Message from your Sales Rep Please contact your Dell sales representative if you have any questions or when you're ready to place an order. Thank you for shopping with Dell! Regards, Daniel Rodriguez Shipping Group Shipping To Shipping Method ALEX YINGST Standard Delivery ONONDAGA COUNTY 421 MONTHGOMERY ST SUB BASEMENT RM 140 SYRACUSE, NY 13202 (315) 435-7743 Product Unit Price Quantity Subtotal Dell Latitude 7220 $1,874.41 1 $1,874.41 Page 1 Dell Marketing LP. U.S. only. Dell Marketing LP. is located at One Dell Way, Mail Stop 8129, Round Rock, TX 78682 Subtotal: $1,874.41 Shipping: $0.00 Non-Taxable Amount: $1,874.41 Taxable Amount: $0.00 Estimated Tax: $0.00 Total: $1,874.41 Special lease pricing may be available for qualified customers. Please contact your DFS Sales Representative for details.