Chapter 4: the MOS Transistor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers

Chapter 7: Transistors, part 2 Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers The transistor amplifiers that we studied in the last chapter have some serious problems for use in AC signals. Their most serious shortcoming is that there is a “dead region” where small signals do not turn on the transistor. So, if your signal is smaller than 0.6 V, or if it is negative, the transistor does not conduct and the amplifier does not work. Design goals for an AC amplifier Before moving on to making a better AC amplifier, let’s define some useful terms. We define the output range to be the range of possible output voltages. We refer to the maximum and minimum output voltages as the rail voltages and the output swing is the difference between the rail voltages. The input range is the range of input voltages that produce outputs which are not at either rail voltage. Our goal in designing an AC amplifier is to get an input range and output range which is symmetric around zero and ensure that there is not a dead region. To do this we need make sure that the transistor is in conduction for all of our input range. How does this work? We do it by adding an offset voltage to the input to make sure the voltage presented to the transistor’s base with no input signal, the resting or quiescent voltage , is well above ground. In lab 6, the function generator provided the offset, in this chapter we will show how to design an amplifier which provides its own offset. -

Role of Mosfets Transconductance Parameters and Threshold Voltage in CMOS Inverter Behavior in DC Mode

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 28 July 2017 doi:10.20944/preprints201707.0084.v1 Article Role of MOSFETs Transconductance Parameters and Threshold Voltage in CMOS Inverter Behavior in DC Mode Milaim Zabeli1, Nebi Caka2, Myzafere Limani2 and Qamil Kabashi1,* 1 Department of Engineering Informatics, Faculty of Mechanical and Computer Engineering ([email protected]) 2 Department of Electronics, Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering ([email protected], [email protected]) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +377-44-244-630 Abstract: The objective of this paper is to research the impact of electrical and physical parameters that characterize the complementary MOSFET transistors (NMOS and PMOS transistors) in the CMOS inverter for static mode of operation. In addition to this, the paper also aims at exploring the directives that are to be followed during the design phase of the CMOS inverters that enable designers to design the CMOS inverters with the best possible performance, depending on operation conditions. The CMOS inverter designed with the best possible features also enables the designing of the CMOS logic circuits with the best possible performance, according to the operation conditions and designers’ requirements. Keywords: CMOS inverter; NMOS transistor; PMOS transistor; voltage transfer characteristic (VTC), threshold voltage; voltage critical value; noise margins; NMOS transconductance parameter; PMOS transconductance parameter 1. Introduction CMOS logic circuits represent the family of logic circuits which are the most popular technology for the implementation of digital circuits, or digital systems. The small dimensions, low power of dissipation and ease of fabrication enable extremely high levels of integration (or circuits packing densities) in digital systems [1-5]. -

Junction Field Effect Transistor (JFET)

Junction Field Effect Transistor (JFET) The single channel junction field-effect transistor (JFET) is probably the simplest transistor available. As shown in the schematics below (Figure 6.13 in your text) for the n-channel JFET (left) and the p-channel JFET (right), these devices are simply an area of doped silicon with two diffusions of the opposite doping. Please be aware that the schematics presented are for illustrative purposes only and are simplified versions of the actual device. Note that the material that serves as the foundation of the device defines the channel type. Like the BJT, the JFET is a three terminal device. Although there are physically two gate diffusions, they are tied together and act as a single gate terminal. The other two contacts, the drain and source, are placed at either end of the channel region. The JFET is a symmetric device (the source and drain may be interchanged), however it is useful in circuit design to designate the terminals as shown in the circuit symbols above. The operation of the JFET is based on controlling the bias on the pn junction between gate and channel (note that a single pn junction is discussed since the two gate contacts are tied together in parallel – what happens at one gate-channel pn junction is happening on the other). If a voltage is applied between the drain and source, current will flow (the conventional direction for current flow is from the terminal designated to be the gate to that which is designated as the source). The device is therefore in a normally on state. -

Basic DC Motor Circuits

Basic DC Motor Circuits Living with the Lab Gerald Recktenwald Portland State University [email protected] DC Motor Learning Objectives • Explain the role of a snubber diode • Describe how PWM controls DC motor speed • Implement a transistor circuit and Arduino program for PWM control of the DC motor • Use a potentiometer as input to a program that controls fan speed LWTL: DC Motor 2 What is a snubber diode and why should I care? Simplest DC Motor Circuit Connect the motor to a DC power supply Switch open Switch closed +5V +5V I LWTL: DC Motor 4 Current continues after switch is opened Opening the switch does not immediately stop current in the motor windings. +5V – Inductive behavior of the I motor causes current to + continue to flow when the switch is opened suddenly. Charge builds up on what was the negative terminal of the motor. LWTL: DC Motor 5 Reverse current Charge build-up can cause damage +5V Reverse current surge – through the voltage supply I + Arc across the switch and discharge to ground LWTL: DC Motor 6 Motor Model Simple model of a DC motor: ❖ Windings have inductance and resistance ❖ Inductor stores electrical energy in the windings ❖ We need to provide a way to safely dissipate electrical energy when the switch is opened +5V +5V I LWTL: DC Motor 7 Flyback diode or snubber diode Adding a diode in parallel with the motor provides a path for dissipation of stored energy when the switch is opened +5V – The flyback diode allows charge to dissipate + without arcing across the switch, or without flowing back to ground through the +5V voltage supply. -

Design of Cascode-Based Transconductance Amplifiers With

Design of Cascode-Based Transconductance Amplifiers with Low-Gain PVT Variability and Gain Enhancement Using a Body-Biasing Technique Nuno Pereira, Luis Oliveira, João Goes To cite this version: Nuno Pereira, Luis Oliveira, João Goes. Design of Cascode-Based Transconductance Amplifiers with Low-Gain PVT Variability and Gain Enhancement Using a Body-Biasing Technique. 4th Doctoral Conference on Computing, Electrical and Industrial Systems (DoCEIS), Apr 2013, Costa de Caparica, Portugal. pp.590-599, 10.1007/978-3-642-37291-9_64. hal-01348806 HAL Id: hal-01348806 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01348806 Submitted on 25 Jul 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Design of Cascode-based Transconductance Amplifiers with Low-gain PVT Variability and Gain Enhancement Using a Body-biasing Technique Nuno Pereira 2, Luis B. Oliveira 1,2 and João Goes 1,2 1 Centre for Technologies and Systems (CTS) – UNINOVA 2 Dept. of Electrical Engineering (DEE), Universidade Nova de Lisboa (UNL) Campus FCT/UNL, 2829-516, Caparica, Portugal [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. -

Analog Integrated Current Drivers for Bioimpedance Applications: a Review

sensors Review Analog Integrated Current Drivers for Bioimpedance Applications: A Review Nazanin Neshatvar * , Peter Langlois, Richard Bayford and Andreas Demosthenous Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering, University College London, Torrington Place, London WC1E 7JE, UK; [email protected] (P.L.); [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (A.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 January 2019; Accepted: 4 February 2019; Published: 13 February 2019 Abstract: An important component in bioimpedance measurements is the current driver, which can operate over a wide range of impedance and frequency. This paper provides a review of integrated circuit analog current drivers which have been developed in the last 10 years. Important features for current drivers are high output impedance, low phase delay, and low harmonic distortion. In this paper, the analog current drivers are grouped into two categories based on open loop or closed loop designs. The characteristics of each design are identified. Keywords: bioimpedance measurement; current driver; integrated circuit; linear feedback; nonlinear feedback; transconductance 1. Introduction Bioimpedance measurement is defined as the study of biological tissue/cell in response to an alternating electric field, which can cover a frequency range from tens of Hz to several MHz [1,2]. The electrical properties of tissue/cell (conductive and dielectric properties) are characterized by frequency variable complex electrical bioimpedance providing important information about the tissue/cell physiology and pathology. In order to measure the bioimpedance, a current stimulus is required to be provided through a set of electrodes and measuring the corresponding potential via the same, or another, pair of electrodes. -

Channel Length Modulation • I Have Been Saying That for a MOSFET in Saturation, the Drain Current Is Independent of the Drain-To-Source Voltage 푉퐷푆 I.E

ECE315 / ECE515 Lecture-2 Date: 06.08.2015 • NMOS I/V Characteristics • Discussion on I/V Characteristics • MOSFET – Second Order Effect ECE315 / ECE515 NMOS I-V Characteristics Gradual Channel Approximation: Cut-off → Linear/Triode → Pinch-off/Saturation Assumptions: • VSB = 0 • VT is constant along the channel • 퐸푥 dominates 퐸푦 => need to consider current flow only in the 푥 −direction • Cutoff Mode: ퟎ ≤ 푽푮푺 ≤ 푽푻 IDS(cutoff) =0 This relationship is very simple—if the MOSFET is in cutoff, the drain current is simply zero ! ECE315 / ECE515 Linear Mode: 푽푮푺 ≥ 푽푻, ퟎ ≤ 푽푫푺 ≤ 푽푫(푺푨푻) => 푽푫푺 ≤ 푽푮푺 − 푽푻 • The channel reaches the drain. Gate VS=0 VDS<VDSAT VGS>VT Oxide Source Drain (p+) (p+) n+ n+ y Channel x x=0 x=L Substrate (p-Si) Depletion region VB=0 • 푉푐(푥): Channel voltage with respect to the source at position 푥. • Boundary Conditions: 푉푐 푥 = 0 = 푉푆 = 0; 푉푐 푥 = 퐿 = 푉퐷푆 ECE315 / ECE515 Linear Mode (Contd.) 푄푑: the charge density along the direction of current = W퐶표푥[푉퐺푆 − 푉푇] where, W = width of the channel and WCox is the capacitance per unit length yd Drain end dx Channel Source end • Now, since the channel potential varies from 0 at source to VDS at the drain 푄푑 푥 = 푊퐶표푥 푉퐺푆 − 푉푐(푥) − 푉푇 , where, Vc(x) = channel potential at 푥. • Subsequently we can write: 퐼퐷 푥 = 푄푑 푥 . 푣 , where, 푣 = velocity of charge (m/s) ECE315 / ECE515 Linear Mode (Contd.) 푣 = 휇푛퐸 ; where, 휇푛 = mobility of charge carriers (electron) dV E = electric field in the channel given by: Ex () dx dV Therefore, I()() x WC V V x V D ox GS c T n dx • Applying the boundary conditions for 푉푐(푥) we can write: xL VV DS IxI().(). -

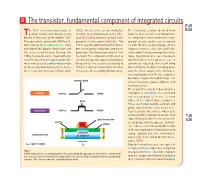

The Transistor, Fundamental Component of Integrated Circuits

D The transistor, fundamental component of integrated circuits he first transistor was made in (SiO2), which serves as an insulator. The transistor, a name derived from Tgermanium by John Bardeen and In 1958, Jack Kilby invented the inte- transfer and resistor, is a fundamen- Walter H. Brattain, in December 1947. grated circuit by manufacturing 5 com- tal component of microelectronic inte- The year after, along with William B. ponents on the same substrate. The grated circuits, and is set to remain Shockley at Bell Laboratories, they 1970s saw the advent of the first micro- so with the necessary changes at the developed the bipolar transistor and processor, produced by Intel and incor- nanoelectronics scale: also well-sui- the associated theory. During the porating 2,250 transistors, and the first ted to amplification, among other func- 1950s, transistors were made with sili- memory. The complexity of integrated tions, it performs one essential basic con (Si), which to this day remains the circuits has grown exponentially (dou- function which is to open or close a most widely-used semiconductor due bling every 2 to 3 years according to current as required, like a switching to the exceptional quality of the inter- “Moore's law”) as transistors continue device (Figure). Its basic working prin- face created by silicon and silicon oxide to become increasingly miniaturized. ciple therefore applies directly to pro- cessing binary code (0, the current is blocked, 1 it goes through) in logic cir- control gate cuits (inverters, gates, adders, and memory cells). The transistor, which is based on the switch source drain transport of electrons in a solid and not in a vacuum, as in the electron gate tubes of the old triodes, comprises three electrodes (anode, cathode and gate), two of which serve as an elec- transistor source drain tron reservoir: the source, which acts as the emitter filament of an electron gate insulator tube, the drain, which acts as the col- source lector plate, with the gate as “control- gate drain ler”. -

Lecture 10 MOSFET (III) MOSFET Equivalent Circuit Models

Lecture 10 MOSFET (III) MOSFET Equivalent Circuit Models Outline • Low-frequency small-signal equivalent circuit model • High-frequency small-signal equivalent circuit model Reading Assignment: Howe and Sodini; Chapter 4, Sections 4.5-4.6 Announcements: 1.Quiz#1: March 14, 7:30-9:30PM, Walker Memorial; covers Lectures #1-9; open book; must have calculator • No Recitation on Wednesday, March 14: instructors or TA’s available in their offices during recitation times 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 10 1 Large Signal Model for NMOS Transistor Regimes of operation: VDSsat=VGS-VT ID linear saturation ID V DS VGS V GS VBS VGS=VT 0 0 cutoff VDS • Cut-off I D = 0 • Linear / Triode: W V I = µ C ⎡ V − DS − V ⎤ • V D L n ox⎣ GS 2 T ⎦ DS • Saturation W 2 I = I = µ C []V − V •[1 + λV ] D Dsat 2L n ox GS T DS Effect of back bias VT(VBS ) = VTo + γ [ −2φp − VBS −−2φp ] 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 10 2 Small-signal device modeling In many applications, we are only interested in the response of the device to a small-signal applied on top of a bias. ID+id + v - ds + VDS v + v gs - - bs VGS VBS Key Points: • Small-signal is small – ⇒ response of non-linear components becomes linear • Since response is linear, lots of linear circuit techniques such as superposition can be used to determine the circuit response. • Notation: iD = ID + id ---Total = DC + Small Signal 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 10 3 Mathematically: iD(VGS, VDS , VBS; vgs, vds , vbs ) ≈ ID()VGS , VDS ,VBS + id (vgs, vds, vbs ) With id linear on small-signal drives: id = gmvgs + govds + gmbvbs Define: gm ≡ transconductance [S] go ≡ output or drain conductance [S] gmb ≡ backgate transconductance [S] Approach to computing gm, go, and gmb. -

Fundamentals of MOSFET and IGBT Gate Driver Circuits

Application Report SLUA618A–March 2017–Revised October 2018 Fundamentals of MOSFET and IGBT Gate Driver Circuits Laszlo Balogh ABSTRACT The main purpose of this application report is to demonstrate a systematic approach to design high performance gate drive circuits for high speed switching applications. It is an informative collection of topics offering a “one-stop-shopping” to solve the most common design challenges. Therefore, it should be of interest to power electronics engineers at all levels of experience. The most popular circuit solutions and their performance are analyzed, including the effect of parasitic components, transient and extreme operating conditions. The discussion builds from simple to more complex problems starting with an overview of MOSFET technology and switching operation. Design procedure for ground referenced and high side gate drive circuits, AC coupled and transformer isolated solutions are described in great details. A special section deals with the gate drive requirements of the MOSFETs in synchronous rectifier applications. For more information, see the Overview for MOSFET and IGBT Gate Drivers product page. Several, step-by-step numerical design examples complement the application report. This document is also available in Chinese: MOSFET 和 IGBT 栅极驱动器电路的基本原理 Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 2 2 MOSFET Technology ...................................................................................................... -

Power MOSFET Basics by Vrej Barkhordarian, International Rectifier, El Segundo, Ca

Power MOSFET Basics By Vrej Barkhordarian, International Rectifier, El Segundo, Ca. Breakdown Voltage......................................... 5 On-resistance.................................................. 6 Transconductance............................................ 6 Threshold Voltage........................................... 7 Diode Forward Voltage.................................. 7 Power Dissipation........................................... 7 Dynamic Characteristics................................ 8 Gate Charge.................................................... 10 dV/dt Capability............................................... 11 www.irf.com Power MOSFET Basics Vrej Barkhordarian, International Rectifier, El Segundo, Ca. Discrete power MOSFETs Source Field Gate Gate Drain employ semiconductor Contact Oxide Oxide Metallization Contact processing techniques that are similar to those of today's VLSI circuits, although the device geometry, voltage and current n* Drain levels are significantly different n* Source t from the design used in VLSI ox devices. The metal oxide semiconductor field effect p-Substrate transistor (MOSFET) is based on the original field-effect Channel l transistor introduced in the 70s. Figure 1 shows the device schematic, transfer (a) characteristics and device symbol for a MOSFET. The ID invention of the power MOSFET was partly driven by the limitations of bipolar power junction transistors (BJTs) which, until recently, was the device of choice in power electronics applications. 0 0 V V Although it is not possible to T GS define absolutely the operating (b) boundaries of a power device, we will loosely refer to the I power device as any device D that can switch at least 1A. D The bipolar power transistor is a current controlled device. A SB (Channel or Substrate) large base drive current as G high as one-fifth of the collector current is required to S keep the device in the ON (c) state. Figure 1. Power MOSFET (a) Schematic, (b) Transfer Characteristics, (c) Also, higher reverse base drive Device Symbol. -

Transconductance 1 Transconductance

Transconductance 1 Transconductance Transconductance is the property of certain electronic components. Conductance is the reciprocal of resistance; transconductance is the ratio of the current change at the output port to the voltage change at the input port. It is written as g . For direct current, transconductance is defined as follows: m For small signal alternating current, the definition is simpler: Terminology Transconductance is a contraction of transfer conductance. The old unit of conductance, the mho (ohm spelled backwards), was replaced by the SI unit, the siemens, with the symbol S (1 siemens = 1 ampere per volt). Transresistance Transresistance, infrequently referred to as mutual resistance, is the dual of transconductance. The term is a contraction of transfer resistance. It refers to the ratio between a change of the voltage at two output points and a related change of current through two input points, and is notated as r : m The SI unit for transresistance is simply the ohm, as in resistance. Devices Vacuum tubes For vacuum tubes, transconductance is defined as the change in the plate(anode)/cathode current divided by the corresponding change in the grid/cathode voltage, with a constant plate(anode)/cathode voltage. Typical values of g m for a small-signal vacuum tube are 1 to 10 millisiemens. It is one of the three 'constants' of a vacuum tube, the other two being its gain μ and plate resistance r or r . The Van der Bijl equation defines their relation as follows: p a [1] Transconductance 2 Field effect transistors Similarly, in field effect transistors, and MOSFETs in particular, transconductance is the change in the drain current divided by the small change in the gate/source voltage with a constant drain/source voltage.