UNSOM Voices Unheard 2019.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gulf Crisis: the Impasse Between Mogadishu and the Regions 4

ei September-October 2017 Volume 29 Issue 5 The Gulf Engulfing the Horn of Africa? Contents 1. Editor's Note 2. Entre le GCC et l'IGAD, les relations bilatérales priment sur l'aspect régional 3. The Gulf Crisis: The Impasse between Mogadishu and the regions 4. Turkish and UAE Engagement in Horn of Africa and Changing Geo-Politics of the Region 1 Editorial information This publication is produced by the Life & Peace Institute (LPI) with support from the Bread for the World, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and Church of Sweden International Department. The donors are not involved in the production and are not responsible for the contents of the publication. Editorial principles The Horn of Africa Bulletin is a regional policy periodical, monitoring and analysing key peace and security issues in the Horn with a view to inform and provide alternative analysis on on-going debates and generate policy dialogue around matters of conflict transformation and peacebuilding. The material published in HAB represents a variety of sources and does not necessarily express the views of the LPI. Comment policy All comments posted are moderated before publication. Feedback and subscriptions For subscription matters, feedback and suggestions contact LPI’s Horn of Africa Regional Programme at [email protected]. For more LPI publications and resources, please visit: www.life-peace.org/resources/ Life & Peace Institute Kungsängsgatan 17 753 22 Uppsala, Sweden ISSN 2002-1666 About Life & Peace Institute Since its formation, LPI has carried out programmes for conflict transformation in a variety of countries, conducted research, and produced numerous publications on nonviolent conflict transformation and the role of religion in conflict and peacebuilding. -

South and Central Somalia Security Situation, Al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups

1/2017 South and Central Somalia Security Situation, al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups Report based on interviews in Nairobi, Kenya, 3 to 10 December 2016 Copenhagen, March 2017 Danish Immigration Service Ryesgade 53 2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: 00 45 35 36 66 00 Web: www.newtodenmark.dk E-mail: [email protected] South and Central Somalia: Security Situation, al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups Table of Contents Disclaimer .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction and methodology ......................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations..................................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Security situation ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. The overall security situation ........................................................................................................ 7 1.2. The extent of al-Shabaab control and presence.......................................................................... 10 1.3. Information on the security situation in selected cities/regions ................................................ 11 2. Possible al-Shabaab targets in areas with AMISOM/SNA presence ....................................................... -

Somalia: COVID-19 Impact Update No. 14 (November 2020)

SOMALIA COVID-19 Impact Update No. 14 November 2020 This report on the Country Preparedness & Response Plan (CPRP) for COVID-19 in Somalia is produced monthly by OCHA and the Integrated Office in collaboration with partners. It contains updates on the response to the humanitarian and socio-economic impact of COVID-19, covering the period from 25 October to 25 November 2020. The next report will be issued in early January 2021. Highli ghts Locations of functional isolation sites Source: OCHA • Somalia’s informal economy, based on remittances, foreign imports and agriculture, has been heavily impacted by COVID-19. Reflecting gender inequalities in the country, women-owned Hargeysa Somaliland businesses were especially hard-hit, with 98 per cent reporting Puntland reduced revenue. • The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated mental distress as Gaalkacyo people living in vulnerable circumstances, including the elderly and Galmudug Galgaduud persons with disabilities, are separated from their caregivers due to State Since March 2020: quarantine and isolation requirements. 4662 reported cases Hir-Shabelle State 124 deaths • The US$256 million humanitarian component of the Somalia COVID-19 CPRP launched in April is only 38 per cent funded, South West Mogadishu negatively impacting effective cluster responses. State Jubaland 14 State isolation units and one quarantine facility were Kismaayo supported during the "second wave" of COVID-19 pandemic Situation overview Confirmed cases by age and gender COVID-19 CASES ECONOMY AT RISK GROWTH CONTRACTION Source: MoH, WHO Over 4,662 confirmed According to the GDP growth estimated cases since 16 March, Heritage Institute of to contract to 2.5% in Age 83% 17% and 124 related deaths. -

Durable Solutions Framework

BENADIR REGION SOMALIA MARCH 2017 LOCAL INTEGRATION FOCUS: BENADIR REGION DURABLE SOLUTIONS FRAMEWORK Review of existing data and assessments to identify gaps and opportunities to inform (re)integration planning and programing for displacement affected communities Durable Solutions Framework - Local Integration Focus: Benadir region 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study could not have been completed without the help of many people. ReDSS gratefully acknowledges the support of the DSRSG/HC/RC office for organizing the consultations in Mogadishu with local authorities and representatives of civil society and for facilitating the validation process with the Durable Solution working group. ReDSS would also like to thank representatives of governments, UN agencies, clusters, NGOs, donors, and displacement affected communities for engaging in this process by sharing their knowledge and expertise and reviewing findings and recommendations at different stages. Without their involvement, it would not have been possible to complete this analysis. ReDSS would also like to express its gratitude to DFID and DANIDA for their financial support and to Ivanoe Fugali for conducting the research and writing this report. ABOUT the Regional Durable Solutions Secretariat (ReDSS) The search for durable solutions to the protracted displacement situation in East and Horn of Africa is a key humanitarian and development concern. This is a regional/cross border issue, dynamic and with a strong political dimension which demands a multi-sectorial response that goes beyond the existing humanitarian agenda. The Regional Durable Solutions Secretariat (ReDSS) was created in March 2014 with the aim of maintaining a focused momentum and stakeholder engagement towards durable solutions for displacement affected communities. The secretariat was established following extensive consultations among NGOs in the region, identifying a wish and a vision to establish a body that can assist stakeholders in addressing durable solutions more consistently. -

Export Agreement Coding (PDF)

Peace Agreement Access Tool PA-X www.peaceagreements.org Country/entity Somalia Region Africa (excl MENA) Agreement name Declaration of National Commitment (Arta Declaration) Date 05/05/2000 Agreement status Multiparty signed/agreed Interim arrangement No Agreement/conflict level Intrastate/intrastate conflict ( Somali Civil War (1991 - ) ) Stage Framework/substantive - partial (Multiple issues) Conflict nature Government/territory Peace process 87: Somalia Peace Process Parties The Transnational Government of Somalia Third parties [Note: Several references to the international community] Description Agreement outlines the responsibilities of the Transitional National Assembly, the election of the Chief Justice, the roles of the President and Prime Minister, particularly, the limitations of power of the President. It includes 17-points of binding principles. The Annexes include a ceasefire; a plan of reconstrution and recovery; and the foundations for representation of the Somali population in the TNA and the national dialogue. Agreement document SO_000505_Declaration of national commitment.pdf [] Groups Children/youth No specific mention. Disabled persons No specific mention. Elderly/age No specific mention. Migrant workers No specific mention. Racial/ethnic/national Substantive group [Summary] Contains substantive consideration of inter-group representation in the Transitional National Assembly. Page 1, • Representation in the Conference and in the "Transitional National Assembly" shall be on the basis of local constituencies (regional /clan mix) Page 3, TOWARD THIS END WE ... 8. pledge to place national interest above clan self interest, personal greed and ambitions Page 6, ANNEX IV BASE OF REPRESENTATION IN THE ... WHAT TO GUARD AGAINST • It must be stressed that representation based on clan affiliations or the assumed strength or importance of certain clan, including the size of territories presumed or traditional belonging to certain clans, would only succeed in perpetuating or reinforcing the division of the nation. -

Afmadow District Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia

Afmadow district Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia Introduction Location map The Detailed Site Assessment (DSA) was triggered in the perspectives of different groups were captured2. KI coordination with the Camp Coordination and Camp responses were aggregated for each site. These were then Management (CCCM) Cluster in order to provide the aggregated further to the district level, with each site having humanitarian community with up-to-date information on an equal weight. Data analysis was done by thematic location of internally displaced person (IDP) sites, the sectors, that is, protection, water, sanitation and hygiene conditions and capacity of the sites and the humanitarian (WASH), shelter, displacement, food security, health and needs of the residents. The first round of the DSA took nutrition, education and communication. place from October 2017 to March 2018 assessing a total of 1,843 sites in 48 districts. The second round of the DSA This factsheet presents a summary of profiles of assessed sites3 in Afmadow District along with needs and priorities of took place from 1 September 2018 to 31 January 2019 IDPs residing in these sites. As the data is captured through assessing a total of 1778 sites in 57 districts. KIs, findings should be considered indicative rather than A grid pattern approach1 was used to identify all IDP generalisable. sites in a specific area. In each identified site, two key Number of assessed sites: 14 informants (KIs) were interviewed: the site manager or community leader and a women’s representative, to ensure Assessed IDP sites in Afmadow4 Coordinates: Lat. 0.6, Long. -

Somalia Hunger Crisis Response.Indd

WORLD VISION SOMALIA HUNGER RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 5 March 2017 RESPONSE HIGHLIGHTS 17,784 people received primary health care 66,256 people provided with KEY MESSAGES 24,150,700 litres of safe drinking water • Drought has led to increased displacement education. In Somaliland more than 118 of people in Somalia. In February 2017 schools were closed as a result of the alone, UNHCR estimates that up to looming famine. 121,000 people were displaced. • Urgent action at this stage has a high • There is a sharp increase in the number of chance of saving over 300,000 children Acute Water Diarrhoea (AWD/cholera) who are acutely malnourished as well cases. From January to March, 875 AWD as over 6 million people facing possible cases and 78 deaths were recorded in starvation across the country. 22,644 Puntland, Somaliland and Jubaland. • Despite encouraging donor contributions, • There is an urgent need to scale up the Somalia humanitarian operational people provided with support for health interventions in the plan is less than 20% funded (UNOCHA, South West State (SWS) especially FTS, 7th March 2017). Approximately 5,917 in districts that have been hard hit by US$825 million is required to reach 5.5 NFI kits outbreaks of Acute Watery Diarrhoea million Somalis facing possible famine until (AWD). Only few agencies have funding June 2017. to support access to health care services. • More than 6 million people or over 50% • According to Somaliland MOH, high of Somalia’s population remain in crisis cases of measles, diarrhea and pneumonia and face possible famine if aid does not have been reported since November as match the scale of need between now main health complications caused by the and June 2017. -

Protection Cluster Update Weekly Report

Protection Cl uster Update Funded by: The People of Japan Weeklyhttp://www.shabelle.net/article.php?id=4297 Report 30 th March 2012 European Commission IASC Somalia •Objective Protection Monitoring Network (PMN) Humanitarian Aid This update provides information on the protection environment in Somalia, including apparent violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law as reported during the last two weeks through the IASC Somalia Protection Cluster monitoring systems. Incidents mentioned in this report are not exhaustive. They are intended to highlight credible reports to inform and prompt programming and advocacy initiatives by the humanitarian community and national authorities. GENERAL OVERVIEW During the reporting period, fighting continued between Al-Shabaab forces and forces supporting the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in Lower Juba, Banadir and Bakool regions resulting in the displacement of people, mainly within these regions and an unknown number of civilian casualties. Heavy fighting erupted between Al Shabaab and Ethiopian forces in Xudur district of Bakool region. The heavy fighting resulted in an unconfirmed number of casualties and the occupation of Xudur district by the pro-TFG forces who subsequently imposed a night-time curfew.1 Indiscriminate attacks against the civilian population, including IDPs remained a major concern over the past two weeks. At least 11 people were killed and 12 others injured during the past two weeks owing to mortars landing in Beerta Darawiishta IDP settlements of Banadir region. Al Shabaab forces are reported to have instructed IDPs to move away from areas surrounding the presidential palace as they intended to continue their attacks. 2 Fighting also erupted between Al Shabaab and Ahlul Sunna Wal-jama’a (ASWJ) in Dhuusamarreeb district of Galgaduud region resulting with approximately 300 displacements arriving mainly in Gaalkacyo district of Mudug and Garowe district of Nugaal region. -

Download=True

“WE LIVE IN PERPETUAL FEAR” VIOLATIONS AND ABUSES OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN SOMALIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Somali journalists denied access to photograph an Al-Shabaab attack site in (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Mogadishu in January 2020. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 52/1442/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND 11 3.1 CONFLICT AND CIVILIAN SUFFERING 11 3.2 MEDIA AND SOCIAL MEDIA USE 12 3.3 TREATMENT OF MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS 12 3.4 HEIGHTENED POLITICAL TENSION IN 2018 AND 2019 13 4. INTERNATIONAL AND REGIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK 15 4.1 NATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK 17 5. -

AFRICA Al-Shabaab Down but Not Out

AFRICA Al-Shabaab Down But Not Out OE Watch Commentary: The fight against al-Shabaab in Somalia has been going on for several years, and there have been reports that the terrorist group has been losing strength and territory. Nevertheless, it is still able to mount significant operations against the Somali National Army, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), and members of the Somali government. As the accompanying excerpted article from The East African reports, not only does the group extort money from businesses in rural areas, but it also operates in the capital city, Mogadishu (from where it was forced out in 2011). Since President Farmaajo assumed office two years ago, AMISOM has reportedly not liberated any new territory. One reason for this might be that the nations contributing troops to that mission frequently pursue different strategies and interests, thus presenting less than a unified Although al Shabaab has been weakened by AMISOM forces and the Somali National Army, it is still able to launch devastating attacks in the country. front. Still another reason might be, with 2020 elections Source: Skilla1st via Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Djiboutian_forces_artillery_ready_to_fire_on_Al-Shabaab_militants_near_the_town_of_ Buula_Burde,_Somalia.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0 approaching, Farmaajo’s government is distracted. Additionally, Farmaajo has poor relations with the leaders of three regional states, possibly compounding the central government’s diificulties in combating the terrorists. While Somali domestic politics play out, and AMISOM shows its fractures, al-Shabaab has taken advantage of the situation to infiltrate government agencies. The killing of Mogadishu’s mayor by one of his staff members who turned out to be a suicide bomber bears testament to that. -

Shabelle Relief and Development Organization (SHARDO)

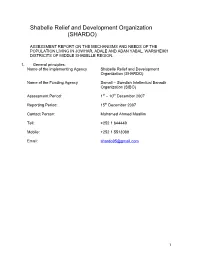

Shabelle Relief and Development Organization (SHARDO) ASSESSMENT REPORT ON THE MECHANISMS AND NEEDS OF THE POPULATION LIVING IN JOWHAR, ADALE AND ADAN YABAL, WARSHEIKH DISTRICITS OF MIDDLE SHABELLE REGION. 1. General principles: Name of the implementing Agency Shabelle Relief and Development Organization (SHARDO) Name of the Funding Agency Somali – Swedish Intellectual Banadir Organization (SIBO) Assessment Period: 1st – 10th December 2007 Reporting Period: 15th December 2007 Contact Person: Mohamed Ahmed Moallim Tell: +252 1 644449 Mobile: +252 1 5513089 Email: [email protected] 1 2. Contents 1. General Principles Page 1 2. Contents 2 3. Introduction 3 4. General Objective 3 5. Specific Objective 3 6. General and Social demographic, economical Mechanism in Middle Shabelle region 4 1.1 Farmers 5 1.2 Agro – Pastoralists 5 1.3 Adale District 7 1.4 Fishermen 2 3. Introduction: Middle Shabelle is located in the south central zone of Somalia The region borders: Galgadud to the north, Hiran to the West, Lower Shabelle and Banadir regions to the south and the Indian Ocean to the east. A pre – war census estimated the population at 1.4 million and today the regional council claims that the region’s population is 1.6 million. The major clans are predominant Hawie and shiidle. Among hawiye clans: Abgal, Galjecel, monirity include: Mobilen, Hawadle, Kabole and Hilibi. The regional consists of seven (7) districts: Jowhar – the regional capital, Bal’ad, Adale, A/yabal, War sheikh, Runirgon and Mahaday. The region supports livestock production, rain-fed and gravity irrigated agriculture and fisheries, with an annual rainfall between 150 and 500 millimeters covering an area of approximately 60,000 square kilometers, the region has a 400 km coastline on Indian Ocean. -

Somalia 2019 Crime & Safety Report

Somalia 2019 Crime & Safety Report This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Mission to Somalia. The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Somalia at Level 4, indicating travelers should not travel to the country due to crime, terrorism, and piracy. Overall Crime and Safety Situation The U.S. Mission to Somalia does not assume responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons or firms appearing in this report. The American Citizen Services unit (ACS) cannot recommend a particular individual or location, and assumes no responsibility for the quality of service provided. Review OSAC’s Somalia-specific page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. The U.S. government recommends U.S. citizens avoid travel to Somalia. Terrorist and criminal elements continue to target foreigners and locals in Somalia. Crime Threats There is serious risk from crime in Mogadishu. Violent crime, including assassinations, murder, kidnapping, and armed robbery, is common throughout Somalia, including in Mogadishu. Other Areas of Concern A strong familiarity with Somalia and/or extensive prior travel to the region does not reduce travel risk. Those considering travel to Somalia, including Somaliland and Puntland, should obtain kidnap and recovery insurance, as well as medical evacuation insurance, prior to travel. Inter- clan, inter-factional, and criminal feuding can flare up with little/no warning. After several years of quiet, pirates attacked several ships in 2017 and 2018.