General Paul Thiã©Bault

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dueling, Honor and Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Spanish Sentimental Comedies

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES Kristie Bulleit Niemeier University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Niemeier, Kristie Bulleit, "DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 12. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/12 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Kristie Bulleit Niemeier The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES _________________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the University of Kentucky By Kristie Bulleit Niemeier Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Ana Rueda, Professor of Spanish Literature Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Kristie Bulleit Niemeier 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION DUELING, HONOR AND -

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte's Invasion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2012 “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London imesT Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia Julia Dittrich East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dittrich, Julia, "“We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1457. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1457 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia _______________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _______________________ by Julia Dittrich August 2012 _______________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. Brian J. Maxson Keywords: Napoleon Bonaparte, The London Times, English Identity ABSTRACT “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia by Julia Dittrich “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia aims to illustrate how The London Times interpreted and reported on Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia. -

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

Austerlitz, Napoleon and the Destruction of the Third Coalition

H-France Review Volume 7 (2007) Page 67 H-France Review Vol. 7 (February 2007), No. 16 Robert Goetz, 1805: Austerlitz, Napoleon and the Destruction of the Third Coalition. Greenhill: London, 2005. 368 pp. Appendices, Maps, Tables, Illustrations and Index. ISBN 1-85367644-6. Reviewed by Frederick C. Schneid, High Point University. Operational and tactical military history is not terribly fashionable among academics, despite its popularity with general readers. Even the “new military history” tends to shun the traditional approach. Yet, there is great utility and significance to studying campaigns and battles as the late Russell Weigley, Professor of History at Temple University often said, “armies are for fighting.” Warfare reflects the societies waging it, and armies are in turn, reflections of their societies. Robert Goetz, an independent historian, has produced a comprehensive account of Austerlitz, emphasizing Austrian and Russian perspectives on the event. “The story of the 1805 campaign and the stunning battle of Austerlitz,” writes Goetz, “is the story of the beginning of the Napoleon of history and the Grande Armée of legend.”[1] Goetz further stresses, “[n]o other single battle save Waterloo would match the broad impact of Austerlitz on the course of European history.”[2] Certainly, one can take exception to these broad sweeping statements but, in short, they properly characterize the established perception of the battle and its impact. For Goetz, Austerlitz takes center stage, and the diplomatic and strategic environment exists only to provide context for the climactic encounter between Napoleon and the Russo-Austrian armies. Austerlitz was Napoleon’s most decisive victory and as such has been the focus of numerous military histories of the Napoleonic Era. -

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

Political, Diplomatic and Military Aspects of Romania's Participation in the First World War

Volume XXI 2018 ISSUE no.2 MBNA Publishing House Constanta 2018 SBNA PAPER OPEN ACCESS Political, diplomatic and military aspects of romania's participation in the first world war To cite this article: M. Zidaru, Scientific Bulletin of Naval Academy, Vol. XXI 2018, pg. 202-212. Available online at www.anmb.ro ISSN: 2392-8956; ISSN-L: 1454-864X doi: 10.21279/1454-864X-18-I2-026 SBNA© 2018. This work is licensed under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License Political, diplomatic and military aspects of romania's participation in the first world war M. Zidaru1 1Romanian Society of Historian. Constanta Branch Abstract: Although linked to the Austro-Hungarian Empire by a secret alliance treaty in 1883, Romania chose to declare itself neutral at the outbreak of hostilities in July 1914, relying on the interpretation of the "casus foederis" clauses. The army was in 1914 -1915 completely unprepared for such a war, public opinion, although pro-Entente in most of it, was not ready for this kind of war, and Ion I. C. Bratianu was convinced that he had to obtain a written assurance from the Russian Empire in view of his father's unpleasant experience from 1877-1878. This article analyze the political and military decisions after Romania entry in Great War. Although linked to the Austro-Hungarian Empire by a secret alliance treaty in 1883, Romania chose to declare itself neutral at the outbreak of hostilities in July 1914, relying on the interpretation of the "casus foederis" clauses. In the south, Romania has three major strategic interests in this region: - defense of the long Danubian border and the land border between the Danube and the Black Sea; - the keep open of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, through which 90% of the Romanian trade were made; - avoiding the isolation or political encirclement of Romania by keeping open the Thessaloniki-Nis- Danube communication, preventing its blocking as a result of local conflicts or taking over under strict control by one of the great powers in the region[1]. -

Of 1808: Ideological Disquiet and Certainty in Moratín Jesús Pérez-Magallón Mcgill University

The “Perfidious Invasion” of 1808: Ideological Disquiet and Certainty in Moratín Jesús Pérez-Magallón McGill University Leandro Fernández de Moratín’s political profile was drawn by Luis Sánchez Agesta in his article, “Moratín and the Political Thought of Enlightened Despotism.” In this article, which is more interested in showing that the famous playwright was in favor of enlightened despotism than in exploring and analyzing Moratín’s political thinking, Sánchez Agesta links Moratín with enlightened despotism in at least three ways: First, by way of Moratín’s participation in governmental politics related to theatrical reform; second, by recalling Moratín’s friendship and intellectual rapport with some of the most representative figures of enlightened despotism; and third, “through the ideas that become clear in his correspondence and in the precepts of his Discurso preliminar ” (573). Sánchez Agesta summarizes Moratín’s ideas as follows: “the reform of customs, the law and the entire order of a society based on traditional principles in order to rebuild it on the basis of utility. Two instruments of reform that oppose the revolutionary spirit are mentioned: the actions of an enlightened government, and the soft, continuous pressure of education” (373). Beyond this brief summary, Sanchez Agesta alludes to what he calls “the pedagogical themes of Moratín’s theater.” In short, the playwright is presented as one more among many of those who shared and supported the tenets of enlightened despotism from within the specific sphere of culture; in this case from within the world of the theater. Although Sánchez Agesta adds that Moratín’s “exact place is not among the afrancesados , but rather among the men of letters of enlightened despotism’s second phase, who were supported by Manuel Godoy,” his opinion is but a complement to the label of afrancesado or collaborationist that Moratín has carried since the War of Independence. -

Download the Full Report

H U M A N ON THEIR WATCH R I G H T S Evidence of Senior Army Officers’ Responsibility WATCH for False Positive Killings in Colombia On Their Watch Evidence of Senior Army Officers’ Responsibility for False Positive Killings in Colombia Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-32507 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2015 978-1-6231-32507 On Their Watch Evidence of Senior Army Officers’ Responsibility for False Positive Killings in Colombia Map .................................................................................................................................... i Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ........................................................................................................... -

Waterloo in Myth and Memory: the Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Waterloo in Myth and Memory: The Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WATERLOO IN MYTH AND MEMORY: THE BATTLES OF WATERLOO 1815-1915 By TIMOTHY FITZPATRICK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Timothy Fitzpatrick defended this dissertation on November 6, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Amiée Boutin University Representative James P. Jones Committee Member Michael Creswell Committee Member Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my Family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Rafe Blaufarb, Aimée Boutin, Michael Creswell, Jonathan Grant and James P. Jones for being on my committee. They have been wonderful mentors during my time at Florida State University. I would also like to thank Dr. Donald Howard for bringing me to FSU. Without Dr. Blaufarb’s and Dr. Horward’s help this project would not have been possible. Dr. Ben Wieder supported my research through various scholarships and grants. I would like to thank The Institute on Napoleon and French Revolution professors, students and alumni for our discussions, interaction and support of this project. -

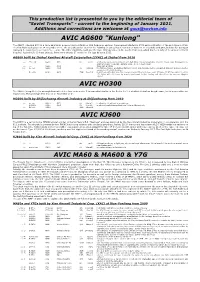

AVIC AG600 "Kunlong"

This production list is presented to you by the editorial team of "Soviet Transports" - current to the beginning of January 2021. Additions and corrections are welcome at [email protected] AVIC AG600 "Kunlong" The AG600 (Jiaolong 600) is a large amphibian powered by four Zhuzhou WJ6 turboprop engines. Development started in 2009 and construction of the prototype in 2014. The first flight took place on 24 December 2017. The aircraft can be used for fire-fighting (it can collect 12 tonnes of water in 20 seconds) and SAR, but also for transport (carrying 50 passengers over up to 5,000 km). The latter capability could give the type strategic value in the South China Sea, which has been subject to various territorial disputes. According to Chinese sources, there were already 17 orders for the type by early 2015. AG600 built by Zhuhai Yanzhou Aircraft Corporation (ZYAC) at Zhuhai from 2016 --- 'B-002A' AG600 AVIC ph. nov20 a full-scale mock-up; in white c/s with dark blue trim and grey belly, titles in Chinese only; displayed in the Jingmen Aviator Town (N30.984289 E112.087750), seen nov20 --- --- AG600 AVIC static test airframe 001 no reg AG600 AVIC r/o 23jul16 the first prototype; production started in 2014, mid-fuselage section completed 29dec14 and nose section completed 17mar15; in primer B-002A AG600 AVIC ZUH 30oct16 in white c/s with dark blue trim and grey belly, titles in Chinese only; f/f 24dec17; f/f from water 20oct18; 172 flights with 308 hours by may20; performed its first landing and take-off on the sea near Qingdao 26jul20 AVIC HO300 The HO300 (Seagull 300) is an amphibian with either four or six seats. -

Race and Immigration in Interwar France Policing Migration And

DOSSIER Race and Immigration in Interwar France THE STRANGENESS OF FOREIGNERS Policing Migration and Nation in Interwar Marseille1 Mary Dewhurst Lewis Harvard University A man has all his moral value, according to us, only in the middle of his fellow cit- izens, in the city where he has always lived under the eyes of those citizens, watched, judged, and appreciated by them … but in general the displaced person, whom we call a vagabond, no longer has his moral value. – Adolphe Thiers2 In April 1924, Stefan X., a young man born in Marseille to Italian immigrants, was imprisoned for failing to honor an expulsion order dating from 1920.3 Protesting his imprisonment, Stefan invoked the French nationality law of 1889, which held that children born in France to foreign parents became French nationals upon reaching adulthood, provided that they remained res- idents of France at that time and did not repudiate their right to French nationality before a justice of the peace. Stefan, who had just passed his twenty-first birthday, argued that he was a citizen and that, as such, he could not be expelled from the country.4 Local officials argued quite the contrary. They pointed out that the origi- nal expulsion order, which had been triggered by Stefan’s theft of charcoal bri- quettes from a barge, was issued when Stefan was still a minor and could not French Politics, Culture & Society, Vol. 20, No. 3, Fall 2002 66 Mary Dewhurst Lewis yet exercise his birthright citizenship. Since he was supposed to have left France three years earlier, they argued, he could hardly claim to have legal res- idency there upon turning age twenty-one.