Austerlitz: Empires Come and Empires Go

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte's Invasion

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2012 “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London imesT Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia Julia Dittrich East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dittrich, Julia, "“We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1457. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1457 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia _______________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _______________________ by Julia Dittrich August 2012 _______________________ Dr. Stephen G. Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. Brian J. Maxson Keywords: Napoleon Bonaparte, The London Times, English Identity ABSTRACT “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia by Julia Dittrich “We Have to Record the Downfall of Tyranny”: The London Times Perspective on Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia aims to illustrate how The London Times interpreted and reported on Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia. -

Annual Report (Abridged)

2015 Department of Records (DoR) Annual Report (Abridged) Note: This is an abridged version of the report. Due to it being published in the winter of 2017, some data is not included as it is updated in real time and does not stay the same as the data at the end of a year does in some reports. We apologize for this and will be sure the missing sections are included in next year’s report. Napoleonic Wargames Club Popular Games and Scenarios: Games Game Battles* Campaign Waterloo (HPS) 407 Campaign Leipzig (JTS) 343 Campaign Eckmühl (HPS) 182 Campaign Austerlitz (HPS) 161 Napoleon's Russian Campaign (HPS) 111 Campaign Jena-Auerstedt (HPS) 103 Campaign Wagram (HPS) 72 Napoleon In Russia (Talonsoft) 65 Bonaparte's Peninsular War (JTS) 63 Campaign Bautzen (JTS) 58 Campaign 1814 (JTS) 54 Battleground Waterloo (Talonsoft) 43 Prelude To Waterloo (Talonsoft) 39 Les Grognards (HistWar) 30 Napoleon's Campaigns (AGEOD) 10 Commander: Napoleon At War 5 Crown of Glory: Emperor's Edition 5 Les Grognards (HistWar) - old version 3 Napoleonic Wargames Club (NWC) © 2016 Battleground Waterloo (Talonsoft, French version) 2 Egypt (mod) 1 The Eagle has Landed (Andy Barns) 0 Crown of Glory 0 Napoleon at Golymin (Greg Gorsuch) 0 Battlefield Eylau (Greg Gorsuch) 0 All 1757 Scenarios** Scenario Battles* The Waterloo Campaign, June 1815 43 The Battle of Quatre Bras - Historical, June 16, 1815 38 Hypothetical battles - v 10 35 #22H. The Battle of Austerlitz (HTH) 32 07. Kutuzov Turns to Fight 27 The Ridge - D'Erlon's Attack - Phase 1 23 14. The Battle of Waterloo 22 The Fall Campaign of 1813 22 Custom scenario 21 Waterloo - Historical 19 002. -

Austerlitz, Napoleon and the Destruction of the Third Coalition

H-France Review Volume 7 (2007) Page 67 H-France Review Vol. 7 (February 2007), No. 16 Robert Goetz, 1805: Austerlitz, Napoleon and the Destruction of the Third Coalition. Greenhill: London, 2005. 368 pp. Appendices, Maps, Tables, Illustrations and Index. ISBN 1-85367644-6. Reviewed by Frederick C. Schneid, High Point University. Operational and tactical military history is not terribly fashionable among academics, despite its popularity with general readers. Even the “new military history” tends to shun the traditional approach. Yet, there is great utility and significance to studying campaigns and battles as the late Russell Weigley, Professor of History at Temple University often said, “armies are for fighting.” Warfare reflects the societies waging it, and armies are in turn, reflections of their societies. Robert Goetz, an independent historian, has produced a comprehensive account of Austerlitz, emphasizing Austrian and Russian perspectives on the event. “The story of the 1805 campaign and the stunning battle of Austerlitz,” writes Goetz, “is the story of the beginning of the Napoleon of history and the Grande Armée of legend.”[1] Goetz further stresses, “[n]o other single battle save Waterloo would match the broad impact of Austerlitz on the course of European history.”[2] Certainly, one can take exception to these broad sweeping statements but, in short, they properly characterize the established perception of the battle and its impact. For Goetz, Austerlitz takes center stage, and the diplomatic and strategic environment exists only to provide context for the climactic encounter between Napoleon and the Russo-Austrian armies. Austerlitz was Napoleon’s most decisive victory and as such has been the focus of numerous military histories of the Napoleonic Era. -

{FREE} Napoleon Bonaparte Ebook

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gregory Fremont-Barnes,Peter Dennis | 64 pages | 25 May 2010 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781846034589 | English | Oxford, England, United Kingdom Napoleon Bonaparte - Quotes, Death & Facts - Biography They may have presented themselves as continental out of a desire for honor and distinction, but this does not prove they really were as foreign as they themselves often imagined. We might say that they grew all the more attached to their Italian origins as they moved further and further away from them, becoming ever more deeply integrated into Corsican society through marriages. This was as true of the Buonapartes as of anyone else related to the Genoese and Tuscan nobilities by virtue of titles that were, to tell the truth, suspect. The Buonapartes were also the relatives, by marriage and by birth, of the Pietrasentas, Costas, Paraviccinis, and Bonellis, all Corsican families of the interior. Napoleon was born there on 15 August , their fourth child and third son. A boy and girl were born first but died in infancy. Napoleon was baptised as a Catholic. Napoleon was born the same year the Republic of Genoa ceded Corsica to France. His father was an attorney who went on to be named Corsica's representative to the court of Louis XVI in The dominant influence of Napoleon's childhood was his mother, whose firm discipline restrained a rambunctious child. Napoleon's noble, moderately affluent background afforded him greater opportunities to study than were available to a typical Corsican of the time. When he turned 9 years old, [18] [19] he moved to the French mainland and enrolled at a religious school in Autun in January Napoleon was routinely bullied by his peers for his accent, birthplace, short stature, mannerisms and inability to speak French quickly. -

The Command and Control of the Grand Armee Napoleon As Organizational Designer

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2009-06 The command and control of the Grand Armee Napoleon as organizational designer Durham, Norman L. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/4722 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE COMMAND AND CONTROL OF THE GRAND ARMEE: NAPOLEON AS ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGNER by Norman L. Durham June 2009 Thesis Advisor: Karl D. Pfeiffer Second Reader: Steven J. Iatrou Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2009 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE The Command and Control of the Grand Armee: 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Napoleon as Organizational Designer 6. AUTHOR(S) Norman L. Durham 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

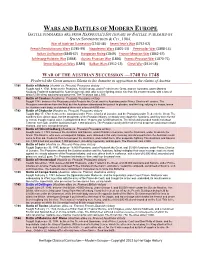

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

Timeline (PDF)

Timeline of the French Revolution 1789 1793 May 5 Estates General convened in Versailles Jan. 21 Execution of Louis XVI (and later, Marie Jun. 17 National Assembly Antoinette on Oct. 16) Jun. 20 Tennis Court Oath Feb. 1 France declares war on British and Dutch (and Jul. 11 Necker dismissed on Spain on Mar. 7) Jul. 13 Bourgeois militias in Paris Mar. 11 Counterrevolution starts in Vendée Jul. 14 Storming of the Bastille in Paris (official start of Apr. 6 Committee of Public Safety formed the French Revolution) Jun. 1-2 Mountain purges Girondins Jul. 16 Necker recalled Jul. 13 Marat assassinated Jul. 20 Great Fear begins in the countryside Jul. 27 Maximilien Robespierre joins CPS Aug. 4 Abolition of feudalism Aug. 10 Festival of Unity and Indivisibility Aug. 26 Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen Sept. 5 Terror the order of the day Oct. 5 Adoption of Revolutionary calendar 1791 1794 Jun. 20-21 Flight to Varennes Aug. 27 Declaration of Pillnitz Jun. 8 Festival of the Supreme Being Jul. 27 9 Thermidor: fall of Robespierre 1792 1795 Apr. 20 France declares war on Austria (and provokes Prussian declaration on Jun. 13) Apr. 5/Jul. 22 Treaties of Basel (Prussia and Spain resp.) Sept. 2-6 September massacres in Paris Oct. 5 Vendémiare uprising: “whiff of grapeshot” Sept. 20 Battle of Valmy Oct. 26 Directory established Sept. 21 Convention formally abolishes monarchy Sept. 22 Beginning of Year I (First Republic) 1797 Oct. 17 Treaty of Campoformio Nov. 21 Berlin Decree 1798 1807 Jul. 21 Battle of the Pyramids Aug. -

Napoleon, Talleyrand, and the Future of France

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2017 Visionaries in opposition: Napoleon, Talleyrand, and the future of France Seth J. Browner Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Browner, Seth J., "Visionaries in opposition: Napoleon, Talleyrand, and the future of France". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2017. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/621 Visionaries in opposition: Napoleon, Talleyrand, and the Future of France Seth Browner History Senior Thesis Professor Kathleen Kete Spring, 2017 2 Introduction: Two men and France in the balance It was January 28, 1809. Napoleon Bonaparte, crowned Emperor of the French in 1804, returned to Paris. Napoleon spent most of his time as emperor away, fighting various wars. But, frightful words had reached his ears that impelled him to return to France. He was told that Joseph Fouché, the Minister of Police, and Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, the former Minister of Foreign Affairs, had held a meeting behind his back. The fact alone that Fouché and Talleyrand were meeting was curious. They loathed each other. Fouché and Talleyrand had launched public attacks against each other for years. When Napoleon heard these two were trying to reach a reconciliation, he greeted it with suspicion immediately. He called Fouché and Talleyrand to his office along with three other high-ranking members of the government. Napoleon reminded Fouché and Talleyrand that they swore an oath of allegiance when the coup of 18 Brumaire was staged in 1799. -

Austerlitz Campaign - December 1805

Austerlitz Campaign - December 1805 The Battle of Austerlitz, also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. In what is widely regarded as the greatest victory achieved by Napoleon, the Grande Armée of France defeated a larger Russian and Austrian army led by Tsar Alexander I and Holy Roman Emperor Francis II. The battle occurred near the village of Austerlitz in the Austrian Empire (modern-day Slavkov u Brna in the Czech Republic). Austerlitz brought the War of the Third Coalition to a rapid end, with the Treaty of Pressburg signed by the Austrians later in the month. After eliminating an Austrian army during the Ulm Campaign, French forces managed to capture Vienna in November 1805. The Austrians avoided further conflict until the arrival of the Russians bolstered Allied numbers. Napoleon sent his army north in pursuit of the Allies, but then ordered his forces to retreat so he could feign a grave weakness. Desperate to lure the Allies into battle, Napoleon gave every indication in the days preceding the engagement that the French army was in a pitiful state, even abandoning the dominant Pratzen Heights near Austerlitz. He deployed the French army below the Pratzen Heights and deliberately weakened his right flank, enticing the Allies to launch a major assault there in the hopes of rolling up the whole French line. A forced march from Vienna by Marshal Davout and his III Corps plugged the gap left by Napoleon just in time. Meanwhile, the heavy Allied deployment against the French right weakened their center on the Pratzen Heights, which was viciously attacked by the IV Corps of Marshal Soult. -

A Reassessment of the British and Allied Economic, Industrial And

A Reassessment of the British and Allied Economic and Military Mobilization in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) By Ioannis-Dionysios Salavrakos The Wars of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Era lasted from 1792 to 1815. During this period, seven Anti-French Coalitions were formed ; France managed to get the better of the first five of them. The First Coalition was formed between Austria and Prussia (26 June 1792) and was reinforced by the entry of Britain (January 1793) and Spain (March 1793). Minor participants were Tuscany, Naples, Holland and Russia. In February 1795, Tuscany left and was followed by Prussia (April); Holland (May), Spain (August). In 1796, two other Italian States (Piedmont and Sardinia) bowed out. In October 1797, Austria was forced to abandon the alliance : the First Coalition collapsed. The Second Coalition, between Great Britain, Austria, Russia, Naples and the Ottoman Empire (22 June 1799), was terminated on March 25, 1802. A Third Coalition, which comprised Great Britain, Austria, Russia, Sweden, and some small German principalities (April 1805), collapsed by December the same year. The Fourth Coalition, between Great Britain, Austria and Russia, came in October 1806 but was soon aborted (February 1807). The Fifth Coalition, established between Britain, Austria, Spain and Portugal (April 9th, 1809) suffered the same fate when, on October 14, 1809, Vienna surrendered to the French – although the Iberian Peninsula front remained active. Thus until 1810 France had faced five coalitions with immense success. The tide began to turn with the French campaign against Russia (June 1812), which precipitated the Sixth Coalition, formed by Russia and Britain, and soon joined by Spain, Portugal, Austria, Prussia, Sweden and other small German States. -

The Use of the Saber in the Army of Napoleon

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Scholarly Volume, Articles 103 DOI 10.1515/apd-2016-0004 The use of the saber in the army of Napoleon Bert Gevaert Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Belgium) Hallebardiers / Sint Michielsgilde Brugge (Belgium) [email protected] Abstract – Though Napoleonic warfare is usually associated with guns and cannons, edged weapons still played an important role on the battlefield. Swords and sabers could dominate battles and this was certainly the case in the hands of experienced cavalrymen. In contrast to gunshot wounds, wounds caused by the saber could be treated quite easily and caused fewer casualties. In 18th and 19th century France, not only manuals about the use of foil and epee were published, but also some important works on the military saber: de Saint Martin, Alexandre Muller… The saber was not only used in individual fights against the enemy, but also as a duelling weapon in the French army. Keywords – saber; Napoleonic warfare; Napoleon; duelling; Material culture; Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA); History “The sword is the weapon in which you should have most confidence, because it rarely fails you by breaking in your hands. Its blows are the more certain, accordingly as you direct them coolly; and hold it properly.” Antoine Fortuné de Brack, Light Cavalry Exercises, 18761 I. INTRODUCTION Though Napoleon (1769-1821) started his own military career as an artillery officer and achieved several victories by clever use of cannons, edged weapons still played an important role on the Napoleonic battlefield. Swords and sabers could dominate battles and this was certainly the case in the hands of experienced cavalrymen. -

War of the Fourth Coalition 1 War of the Fourth Coalition

War of the Fourth Coalition 1 War of the Fourth Coalition The Fourth Coalition against Napoleon's French Empire was defeated in a war spanning 1806–1807. Coalition partners included Prussia, Russia, Saxony, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Many members of the coalition had previously been fighting France as part of the Third Coalition, and there was no intervening period of general peace. In 1806, Prussia joined a renewed coalition, fearing the rise in French power after the defeat of Austria and establishment of the French-sponsored Confederation of the Rhine. Prussia and Russia mobilized for a fresh campaign, and Prussian troops massed in Saxony. Overview Napoleon decisively defeated the Prussians in a lightning campaign that culminated at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt on 14 October 1806. French forces under Napoleon occupied Prussia, pursued the remnants of the shattered Prussian Army, and captured Berlin on October 25, 1806. They then advanced all the way to East Prussia, Poland and the Russian frontier, where they fought an inconclusive battle against the Russians at Eylau on 7–8 February 1807. Napoleon's advance on the Russian frontier was briefly checked during the spring as he revitalized his army. Russian forces were finally crushed by the French at Friedland on June 14, 1807, and three days later Russia asked for a truce. By the Treaties of Tilsit in July 1807, France made peace with Russia, which agreed to join the Continental System. The treaty however, was particularly harsh on Prussia as Napoleon demanded much of Prussia's territory along the lower Rhine west of the Elbe, and in what was part of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.