Forced Laborers in the Third Reich: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust Archaeology: Archaeological Approaches to Landscapes of Nazi Genocide and Persecution

HOLOCAUST ARCHAEOLOGY: ARCHAEOLOGICAL APPROACHES TO LANDSCAPES OF NAZI GENOCIDE AND PERSECUTION BY CAROLINE STURDY COLLS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The landscapes and material remains of the Holocaust survive in various forms as physical reminders of the suffering and persecution of this period in European history. However, whilst clearly defined historical narratives exist, many of the archaeological remnants of these sites remain ill-defined, unrecorded and even, in some cases, unlocated. Such a situation has arisen as a result of a number of political, social, ethical and religious factors which, coupled with the scale of the crimes, has often inhibited systematic search. This thesis will outline how a non- invasive archaeological methodology has been implemented at two case study sites, with such issues at its core, thus allowing them to be addressed in terms of their scientific and historical value, whilst acknowledging their commemorative and religious significance. -

Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe Germany National Affairs X. JLALFWAY THROUGH Chancellor Gerhard Schroder's four-year term it was clear that his Red-Green coalition—his own Social Democratic Party (SPD) together with the environmentalist Greens—had succeeded in co-opting the traditional agenda of the opposition Christian Democrats (CDU), leaving the opposition without a substantial issue. The government accomplished this by moving to the political center, primarily through a set of pro-business tax cuts that were expected to spur the economy. The conservative opposition was also handicapped by scandal. Former chan- cellor Helmut Kohl shocked the nation at the end of 1999 by refusing to clarify his role in the CDU's financial irregularities, and in January 2000 he resigned as honorary chairman of the party. The affair continued to get headlines through- out 2000 as more illegal payments during the Kohl years came to light. All that Kohl himself would acknowledge was his personal receipt of some $1 million not accounted for in the party's financial records, but he refused to name the donors. Considering his "word of honor" not to divulge the source of the money more important than the German law requiring him to do so, he compared his treat- ment by the German mass media to the Nazi boycott of Jewish stores during the Hitler regime. Most observers believed that Kohl would end up paying a fine and would not serve any jail time. The Kohl scandal triggered an internal party upheaval. Wolfgang Schauble, Kohl's successor as CDU leader, admitted in February that he too had taken un- reported campaign contributions, and was forced to resign. -

Eastern Europe

NAZI PLANS for EASTE RN EUR OPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies SECRET NAZI PLANS for EASTERN EUROPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies hy Ihor Kamenetsky ---- BOOKMAN ASSOCIATES :: New York Copyright © 1961 by Ihor Kamenetsky Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 61-9850 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY UNITED PRINTING SERVICES, INC. NEW HAVEN, CONN. TO MY PARENTS Preface The dawn of the twentieth century witnessed the climax of imperialistic competition in Europe among the Great Pow ers. Entrenched in two opposing camps, they glared at each other over mountainous stockpiles of weapons gathered in feverish armament races. In the one camp was situated the Triple Entente, in the other the Triple Alliance of the Central Powers under Germany's leadership. The final and tragic re sult of this rivalry was World War I, during which Germany attempted to realize her imperialistic conception of M itteleuropa with the Berlin-Baghdad-Basra railway project to the Near East. Thus there would have been established a transcontinental highway for German industrial and commercial expansion through the Persian Gull to the Asian market. The security of this highway required that the pressure of Russian imperi alism on the Middle East be eliminated by the fragmentation of the Russian colonial empire into its ethnic components. Germany· planned the formation of a belt of buffer states ( asso ciated with the Central Powers and Turkey) from Finland, Beloruthenia ( Belorussia), Lithuania, Poland to Ukraine, the Caucasus, and even to Turkestan. The outbreak and nature of the Russian Revolution in 1917 offered an opportunity for Imperial Germany to realize this plan. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Hans Kammler, Hitler's Last Hope, in American Hands

WORKING PAPER 91 Hans Kammler, Hitler’s Last Hope, in American Hands By Frank Döbert and Rainer Karlsch, August 2019 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann and Charles Kraus, Series Editors This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources from all sides of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. Among the activities undertaken by the Project to promote this aim are the Wilson Center's Digital Archive; a periodic Bulletin and other publications to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for historians to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; and international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars. The CWIHP Working Paper series provides a speedy publication outlet for researchers who have gained access to newly-available archives and sources related to Cold War history and would like to share their results and analysis with a broad audience of academics, journalists, policymakers, and students. CWIHP especially welcomes submissions which use archival sources from outside of the United States; offer novel interpretations of well-known episodes in Cold War history; explore understudied events, issues, and personalities important to the Cold War; or improve understanding of the Cold War’s legacies and political relevance in the present day. -

Local Agency and Individual Initiative in the Evolution of the Holocaust: the Case of Heinrich Himmler

Local Agency and Individual Initiative in the Evolution of the Holocaust: The Case of Heinrich Himmler By: Tanya Pazdernik 25 March 2013 Speaking in the early 1940s on the “grave matter” of the Jews, Heinrich Himmler asserted: “We had the moral right, we had the duty to our people to destroy this people which wanted to destroy us.”1 Appointed Reichsführer of the SS in January 1929, Himmler believed the total annihilation of the Jewish race necessary for the survival of the German nation. As such, he considered the Holocaust a moral duty. Indeed, the Nazi genocide of all “life unworthy of living,” known as the Holocaust, evolved from an ideology held by the highest officials of the Third Reich – an ideology rooted in a pseudoscientific racism that rationalized the systematic murder of over twelve million people, mostly during just a few years of World War Two. But ideologies do not murder. People do. And the leader of the Third Reich, Adolf Hitler, never personally murdered a single Jew. Instead, he relied on his subordinates to implement his often ill-defined visions. Thus, to understand the Holocaust as a broad social phenomenon we must refocus our lens away from an obsession with Hitler and onto his henchmen. One such underling was indeed Himmler. The problem in the lack of consensus among scholars is over the matter of who, precisely, bears responsibility for the Holocaust. Historians even sharply disagree about the place of Adolf Hitler in the decision-making processes of the Third Reich, particularly in regards to the Final Solution. -

6. DV-BEG.Pdf

Ein Service des Bundesministeriums der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz sowie des Bundesamts für Justiz ‒ www.gesetze-im-internet.de Sechste Verordnung zur Durchführung des Bundesentschädigungsgesetzes (6. DV-BEG) 6. DV-BEG Ausfertigungsdatum: 23.02.1967 Vollzitat: "Sechste Verordnung zur Durchführung des Bundesentschädigungsgesetzes vom 23. Februar 1967 (BGBl. I S. 233), die zuletzt durch § 1 der Verordnung vom 24. November 1982 (BGBl. I S. 1571) geändert worden ist" Stand: Zuletzt geändert durch § 1 V v. 24.11.1982 I 1571 Fußnote (+++ Textnachweis Geltung ab: 18.9.1965 +++) Eingangsformel Auf Grund des § 42 Abs. 2 des Bundesentschädigungsgesetzes in der Fassung des Gesetzes vom 29. Juni 1956 (Bundesgesetzbl. I S. 559, 562), zuletzt geändert durch das Gesetz vom 14. September 1965 (Bundesgesetzbl. I S. 1315), verordnet die Bundesregierung mit Zustimmung des Bundesrates: § 1 Als Konzentrationslager im Sinne des § 31 Abs. 2 BEG sind die in der Anlage aufgeführten Haftstätten anzusehen. § 2 (1) Soweit in der Anlage für einzelne Haftstätten bestimmte Zeiträume angegeben sind, gelten diese Haftstätten nur für die angegebenen Zeiträume als Konzentrationslager im Sinne des § 31 Abs. 2 BEG. (2) Die übrigen in der Anlage aufgeführten Haftstätten sind für den Zeitraum als Konzentrationslager im Sinne des § 31 Abs. 2 BEG anzusehen, während dem sie als geschlossene Lager in der Verwaltungsform eines Konzentrationslagers bestanden haben. Dies gilt insbesondere für die Zeiträume, in denen die Haftstätten dem Inspekteur der Konzentrationslager im SS-Hauptamt oder dem SS-Wirtschaftsverwaltungshauptamt, Amtsgruppe D, unterstanden haben. (3) Soweit in der Anlage für einzelne Haftstätten keine bestimmten Zeiträume angegeben sind, wird vermutet, daß diese Haftstätten am 1. November 1943 bestanden haben und von diesem Zeitpunkt an Konzentrationslager im Sinne des § 31 Abs. -

Begründung Satzungsbeschluss

Anlage2zurVorlage0801/2014/6B BebauungsplanNr.4/11 Berthold-Beitz-Boulevard 3.Bauabschnitt# Stadtbezirk: Stadtteil: Westviertel Begr$ndungeinschlie%lichUmweltbericht vom:16.06.2014 Satzungsbeschlussgem.'10Baugesetzbuch(Bau)B) AmtfürStadtplanungundBauordnung S TA D T ESSEN BebauungsplanNr.4/11,Berthold-Beitz-Boulevard.3.Bauabschnitt0 nhalt: Inhalt: I. R,umlicher-eltungsbereich . II. AnlassderPlanungundEntwic0lungsziele 1 1. AnlassderPlanung 1 2. Entwic0lungsziele 1 III. PlanungsrechtlicheSituation 3 1. Regionaler4l,chennutzungsplan5R4NP6 3 2. Bebauungspl,ne 3 3. SonstigePlanungen 3 I7. Bestandsbeschreibung 8 1. 9istorie 8 2. St,dtebaulicheSituation 8 3. 7er0ehr 8 4. TechnischeInfrastru0tur 8 4.1. 1nt23sserung 8 .. Natur LandschaftundArtenschutz 8 1. Baugrund/Altlasten/Bergbau 9 3. Immissionen 10 7. St,dtebaulichesKonzept 11 1. 7ariantenuntersuchung 11 2. Entwurfsbeschreibung 11 3. Auswir0ungenderPlanung 11 7I. Planinhalt 1. 1. Planungsrechtliche4estsetzungen 1. 1.1. ArtderbaulichenNutzung('4Abs.1Nr.1Bau)B) 15 1.2. 6a7derbaulichenNutzung('4Abs.1Nr.1Bau)B) 15 1.3. Bau2eise/8berbaubare)rundstücksfl3che/StellungbaulicherAnlagen('4Abs.1Nr.2 Bau)B) 15 1.4. Verkehrsfl3chen('4Abs.1Nr.11Bau)B) 16 2 BebauungsplanNr.4/11,Berthold-Beitz-Boulevard.3.Bauabschnitt0 nhalt: 1.5. AnpflanzenvonB3umen.Str3uchernundsonstigenBepflanzungen('4Abs.1Nr.25a Bau)B) 16 1.6. BaulicheundsonstigeVorkehrungenzumSchutzvorsch3dlichen9m2eltein2irkungen('4 Abs.1Nr.24Bau)B) 17 2. Kennzeichnungen 18 2.1. Fl3chen.derenB<denerheblichmitum2eltgef3hrdendenStoffenbelastetsind('4Abs. -

Journalists and Religious Activists in Polish-German Relations

THE PROJECT OF RECONCILIATION: JOURNALISTS AND RELIGIOUS ACTIVISTS IN POLISH-GERMAN RELATIONS, 1956-1972 Annika Frieberg A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Dr. Konrad H. Jarausch Dr. Christopher Browning Dr. Chad Bryant Dr. Karen Hagemann Dr. Madeline Levine View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository ©2008 Annika Frieberg ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ANNIKA FRIEBERG: The Project of Reconciliation: Journalists and Religious Activists in Polish-German Relations, 1956-1972 (under the direction of Konrad Jarausch) My dissertation, “The Project of Reconciliation,” analyzes the impact of a transnational network of journalists, intellectuals, and publishers on the postwar process of reconciliation between Germans and Poles. In their foreign relations work, these non-state actors preceded the Polish-West German political relations that were established in 1970. The dissertation has a twofold focus on private contacts between these activists, and on public discourse through radio, television and print media, primarily its effects on political and social change between the peoples. My sources include the activists’ private correspondences, interviews, and memoirs as well as radio and television manuscripts, articles and business correspondences. Earlier research on Polish-German relations is generally situated firmly in a nation-state framework in which the West German, East German or Polish context takes precedent. My work utilizes international relations theory and comparative reconciliation research to explore the long-term and short-term consequences of the discourse and the concrete measures which were taken during the 1960s to end official deadlock and nationalist antagonisms and to overcome the destructive memories of the Second World War dividing Poles and Germans. -

Meine Letzte Kippe Vor Dem Rauchverbot Die Letzte Zigarette Qualmen Große Zukunft Investiert Und Sich Viele Raucher*Innen Am 30

Studentische Zeitung Nummer 18 für Duisburg, Essen 24. April und das Ruhrgebiet 2013 CAMPING AM CAMPUS CAMPUSFEST AKDUELL IM NETZ Nach Seminaren in Containern und Endlich findet wieder ein Campus- Alle Artikel, die Möglichkeit Klausurorten wie der Gruga Mes- fest statt. Der AStA organisiert unter zu Kommentieren und sehalle, jetzt auch Veranstaltungen dem Motto „von Studis für Studis“ noch viel mehr gibt es im in Zelten am Duisburger Campus. ein langersehntes Sommerfest. Internet unter der Adresse: Ω Seite 2 Ω Seite 4/5 Ω www.akduell.de Meine letzte Kippe vor dem Rauchverbot Die letzte Zigarette qualmen große Zukunft investiert und sich viele Raucher*innen am 30. April. Foto: understandinganimalresearch.org.uk ( CC BY 2.0) gutgläubig auf die Regierung verlas- Zumindest im öffentlichen Raum sen. Da stelle ich die Frage: Leistet tritt am nächsten Tag das Nicht- jemand Schadenersatz?“ raucherschutzgesetz Nordrhein- Existenzbedrohte Shisha-Cafés Westfalen in Kraft. Das bedeutet, dass in öffentlichen Gebäuden, Für Shisha-Bars dagegen stellt das Freizeiteinrichtungen wie Kneipen Verbot eine klare Existenzbedro- oder Sportstätten, sofern sie nicht hung dar. Viele Gastronom*innen geöffnet sind, nicht mehr geraucht fürchten das Aus. Der Gesetzesent- werden darf. Ich habe mich mit ei- wurf bleibt schwammig: Ein kleiner, ner letzten Schachtel in der Hand nicht genau bezifferbarer Anteil der zu Plätzen aufgemacht, an denen getränkeorientierten Kleingastro- auch Studis in Zukunft nicht mehr nomie mit einem hohen Anteil an am Glimmstängel ziehen dürfen. rauchender Stammkundschaft sowie Shisha-Bars, würden Nachteile hin- Die erste Zigarette rauche ich auf mac Foto: nehmen müssen. Die betroffenen dem Campus Essen. Im „Café Rosso“ Unternehmer*innen müssten auf vom Studentenwerk im Gebäude R12 nicht so schnell rieche wie Nikotin- sitze, das ist klar. -

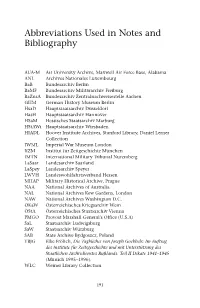

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Glossary of Key Terms

Project Sounds in the silence – glossary of terms1 Allies of the Second World War The Allies of the Second World War (formalised by Declaration by United Nations of 1 January 1942), were the countries that together opposed German, Japanese and Italian aggression during the Second World War (1939–1945). Germany, Japan and Italy were called the Axis powers. At the start of the war on 1 September 1939, the Allies consisted of France, Poland and the United Kingdom, as well as their dependent states, such as British India. Within days they were joined by the independent Dominions of the British Commonwealth: Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. After the start of the German invasion of North Europe until the Balkan Campaign, the Netherlands, Belgium, Greece, and Yugoslavia joined the Allies. After first having cooperated with Germany in invading Poland whilst remaining neutral in the Allied-Axis conflict, the Soviet Union joined the Allies in June 1941 after being invaded by Germany. The United States officially joined in December 1941 after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. China had already been in a prolonged war with Japan since 1937, but officially joined the Allies in 1941. Civilian Forced Labourers (German: Zivile Zwangsarbeiter) Modern term for forced labourers who were not prisoners of war or concentration camp inmates. In the summer of 1944, there were about 5.7 million civilian foreign workers in the German Reich. They were employed by private companies, government agencies, farmers and families who also provided them with accommodation and kept them under surveillance. This term differs from forced labourers who were prisoners of war (POW), as such under the control of the Wehrmacht and imprisoned in POW camps.