Oleg Maltsev and the Mythical History of Salvatore Giuliano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guerilla Warfare a Sicilian Bandit

RIGHT An American Marine medic administers plasma to a wounded soldier behind the front line in the streets of San Agata, during the Allied invasion of Sicily. Guerilla Warfare With a small but extremely tough volunteer army, the movement for independence in Sicily—which represented a variation on the old and unattainable Mafi a dream of becoming a state—began its armed struggle in the autumn of 1944, partly as a reaction to the continual and arbitrary attacks carried out by the police forces against its offi ces and supporters. Their attempt to bring about a separatist insurrection gave rise to vehement resistance, leading to guerilla warfare. The Italian government was forced to send the army to Sicily to support the police and Carabinieri and to put down the revolt. On June 17, 1945, the commander and founder of the separatist army, Antonio Canepa, was killed in a gunfi ght with the Carabinieri. His death pro- voked many well-founded suspicions that the Mafi a was directly responsible. Given their antipathy to words such as “socialism” and “revolution,” they were no doubt keen to rid themselves of such a subversive combatant. A Sicilian Bandit Concetto Gallo became the new head of the separatist army and then entered into an alliance with the bandits hoping to achieve victory for the revolt. He proposed that the most famous and wanted bandit in all of Sicily, Salvatore Giuliano, should join the volunteer army for the movement for Sicilian independence. Giuliano accepted, and he and his band carried out a series of attacks on the police and Carabinieri as well as on the troops sent by Rome to halt the progress of the rebel- lion. -

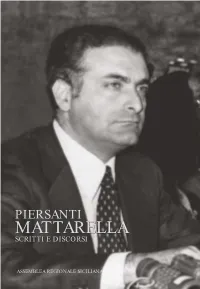

Piersanti Mattarella

Piersanti Mattarella Piersanti Mattarella nacque a Castellammare del Golfo il 24 maggio 1935. Secondogenito di Bernardo Mattarella, uomo politico della Democrazia Cristiana e fratello di Sergio, 12° Presidente della Repubblica Italiana. Piersanti si trasferì a Roma con la famiglia nel 1948. Studiò al San Leone Magno, retto dai Fratelli maristi, e militò nell’Azione cattolica mostrandosi battagliero sostenitore della dottrina sociale della Chiesa che si andava affermando. Si laureò a pieni voti in Giurisprudenza alla Sapienza con una tesi in economia politica, sui problemi dell’integrazione economica europea. Tornò in Sicilia nel 1958 per sposarsi. Divenne assistente ordinario di diritto privato all'Università di Palermo. Ebbe due figli: Bernardo e Maria. Entrò nella Dc tra il 1962 e il 1963 e nel novembre del 1964 si candidò nella relativa lista alle elezioni comunali di Palermo ottenendo più di undicimila preferenze, divenendo consigliere comunale nel pieno dello scandalo del “Sacco di Palermo”. Erano, infatti, gli anni della crisi della Dc in Sicilia, c’era una spaccatura, si stavano affermando Lima e Ciancimino e si preparava il tempo in cui una colata di cemento avrebbe spazzato via le ville liberty di Palermo. Nel 1967 entrò nell’Assemblea Regionale. In politica adottò uno stile tutto suo: parlò di trasparenza, proponendo di ridurre gli incarichi (taglio degli assessorati da dodici ad otto e delle commissioni legislative da sette a cinque e per l'ufficio di presidenza la nomina di soli due vice, un segretario ed un questore) e battendosi per la rotazione delle persone nei centri di potere con dei limiti temporali, in modo da evitare il radicarsi di consorterie pericolose. -

The Gangster Hero in the Work of Puzo, Coppola, and Rimanelli

Rewriting the Mafioso: The Gangster Hero in the Work of Puzo, Coppola, and Rimanelli Author: Marissa Sangimino Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104214 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2015 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Rewriting the Mafioso: The Gangster Hero in the Work of Puzo, Coppola, and Rimanelli By Marissa M. Sangimino Advisor: Prof. Carlo Rotella English Department Honors Thesis Submitted: April 9, 2015 Boston College 2015 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS!! ! ! I!would!like!to!thank!my!advisor,!Dr.!Carlo!Rotella!for!the!many!hours!(and!many!emails)!that!it! took!to!complete!this!thesis,!as!well!as!his!kind!support!and!brilliant!advice.! ! I!would!also!like!to!thank!the!many!professors!in!the!English!Department!who!have!also! inspired!me!over!the!years!to!continue!reading,!writing,!and!thinking,!especially!Professor!Bonnie! Rudner!and!Dr.!James!Smith.! ! Finally,!as!always,!I!must!thank!my!family!of!Mafiosi:!! Non!siamo!ricchi!di!denaro,!ma!siamo!ricchi!di!sangue.! TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.........................................................................................................................................1-3 CHAPTER ONE: The Hyphenate Individual ..............................................................................................................4-17 The -

Who Was Partisan Canepa?

GLORY TO OUR COMRADE ANTONIO CANEPA and to the partisans of the Volunteer Army for the Independence of Sicily! NO to the hypocritical tricoloured Liberation Day and to the tainted May Day celebrations! World War II (1939-1945). After the facts were cleaned out by the ideologies, our very own Memory was "purified", what is left of the second WORLD WAR is a lethal confrontation between competing Powers, which turned into the division of the World in two parts, of a divided Europe, a divided Germany, a divided Berlin. And in the long-lasting withdrawal of the old colonialist European Empires, that had "won" the war, triggering India's independence, and most of all the foundation of Mao's People's Republic of China. In July 1943 - with Operation Husky - the "Allies" (supported by an efficient Resistance against Nazi- fascism) occupy Sicily. It was the beginning of the end of a Regime, but, as we will see, it was not what the Sicilian Partisans had fought for. The 24th October 1943, beyond the temporary AMGOT (Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories), was also the birthdate of Washington's "SICILY REGION 1" in the Mediterranean, which remains like an "unsaid" under this sky that is populated by foreign planes, assassin drones, dysfunctional saints and a G7 on a tourist trip. This Sicily is a fought-over island, played like a geopolitical card by Rome, the real mafia capital, and its strategic relation with the AmeriKan friend. A treasure island reduced to Europe's poorhouse, with its habitants being forced to emigrate. -

Riflessioni Sull™Enigmatica Strage Di Portella Delle

www.laltrasicilia.org RIFLESSIONI SULL’ENIGMATICA STRAGE DI PORTELLA DELLE GINESTRE Dott. Salvatore Riggio Scaduto Nel giugno del 1987 a Montelepre veniva pubblicato dalla casa editrice “La Rivalsa” un corposo libro di 342 pagine, avente inoltre un’appendice fotografica e documentale, intitolato “MIO FRATELLO SALVATORE GIULIANO” degli autori Marianna Giuliano e Giuseppe Sciortino Giuliano, rispettivamente sorella e nipote di Salvatore Giuliano. Dall’introduzione firmata solo dal secondo autore, figlio di Marianna Giuliano, apprendiamo, però, che il libro è stato scritto soltanto da questo, tanto è vero che a pag. 8 si legge che “Il merito maggiore va a mia madre....La sorella di Turiddu, che con lui condivise gli ideali e che lo affiancò nella lotta sia armata che politica. Senza di lei... Forse non sarei mai riuscito nel mio compito”. Il detto libro ha chiaramente e certamente finalità apologetiche e giustificative del personaggio che per circa sette anni tenne a scacco nell’immediato dopoguerra le forze dello Stato Italiano, ma è altrettanto certo che la sorella di Turiddu Giuliano, Marianna, coniugata con Pasquale Sciortino, fu la confidente prediletta del fratello e quindi la depositaria di tantissimi segreti. Uno storico attento e scrupoloso non può liquidare sic et simpliciter i fatti riportati nel detto libro come non veritieri perché di parte, ma deve saper sottoporre a vaglio critico tali fatti con le risultanze di altre fonti. Volendo anch’io strizzare qualche gocciolina della mia penna nel fiume impetuoso d’inchiostro versato sull’oscura strage di Portella delle Ginestre del 1° Maggio 1947, mi cimenterò con il presente scritto a fare alcune considerazioni tenendo anche presente “la verità” ammanitaci in proposito del detto libro da pag. -

Banca Del Mezzogiorno – Mediocredito Centrale S.P.A

Banca del Mezzogiorno – MedioCredito Centrale S.p.A. Inaugural Social Bond Executive Summary • Strategic Government-linked entity promoting investments in the South of Italy • Unique business model focused on development support • Strong financials within the Italian banking system • Rated Ba1 by Moody’s / BBB- by S&P • Inaugural Social Bond Transaction 2 Content 1 MedioCredito Centrale ("MCC") Overview 2 Financial Overview 3 Social Framework 4 Transaction Overview MCC Overview Group Profile and Mission MCC at a Glance MedioCredito Centrale S.p.A.: a Bank 100% owned by Italian State through Invitalia MCC Evolution and Overview Board of Directors • Established in 1952 as a public entity, its mission was Chairman Massimiliano CESARE focused on delivering public finance and supporting the expansion of Italian companies overseas. In 2011, following CEO Bernardo MATTARELLA the MEF developing program for the southern Italy, its corporate name was changed to Banca del Mezzogiorno- Directors Pasquale AMBROGIO MedioCredito Centrale Gabriella FORTE • Since August 2017 the Bank has been owned by Invitalia Leonarda SANSONE S.p.A. (formerly Sviluppo Italia S.p.A.) and regulated by the Bank of Italy with a full banking licence • No branch network (Banca di II Livello), MCC operates under Shareholding Structure cooperation agreements with the main Italian banking groups • Total employees as of 31/12/2018, 283: 14 managers, 163 senior officers and 106 employees (and 9 trainees) Board of Statutory Auditors Chairman Paolo PALOMBELLI Standing Auditors Carlo FEROCINO 100% Marcella GALVANI 100% Alternative Auditors Roberto MICOLITTI Sofia PATERNOSTRO 5 Key Stages of MCC’s Development A more than 60 years long history of success, with focus on South of Italy SMEs development since 2011 1952 1994 1999 2007 2011 2017 TODAY Poste Italiane acquires 100% of Law no. -

Piersanti Mattarella Scritti E Discorsi

PIERSANTI MATTARELLA SCRITTI E DISCORSI ASSEMBLEA REGIONALE SICILIANA PIERSANTI MATTARELLA nato a Castellammare del Golfo (Tp) il 24 maggio 1935, assassinato a Palermo il 6 gennaio 1980, gior- no dell’Epifania. Ha ricoperto importanti incarichi diocesani, regiona- li e nazionali nella gioventù di azione cattolica, della cui presidenza ha fatto parte per cinque anni. Consigliere comunale di Palermo dal 1964 al 1967. Componente della direzione regionale, del Consiglio nazionale e della direzione centrale della Democrazia cristiana. Deputato regionale eletto per la D.C. nel collegio di Palermo nella sesta (11 giugno 1967), settima (13 giugno 1971) e ottava legislatura (20 giugno 1976). Nella sesta legislatura è stato componente delle Commissioni legislative permanenti per gli affari interni e per la pubblica istruzione, della giunta di bilancio, della Commissione per il regolamento interno, della Commissione speciale per la riforma burocratica e della Commissione speciale per la rifor- ma urbanistica. Nella settima legislatura ha ricoperto ininterrotta- mente la carica di Assessore alla Presidenza, delegato al bilancio, carica nella quale è stato riconfermato nel primo governo della ottava legislatura. Dal 16 marzo 1978 era Presidente della Regione. ASSEMBLEA REGIONALE SICILIANA XIII LEGISLATURA SCRITTI E DISCORSI di PIERSANTI MATTARELLA VOLUME SECONDO 2 QUADERNI DEL SERVIZIO STUDI LEGISLATIVI DELL’A.R.S. – NUOVA SERIE – SCRITTI E DISCORSI DI PIERSANTI MATTARELLA Introduzione di LEOPOLDO ELIA VOLUME SECONDO ASSEMBLEA REGIONALE SICILIANA Il ruolo delle regioni meridionali per una nuova politica economica dello Stato (*) Palermo, 31 gennaio 1971 Il problema principale da affrontare e risolvere al fine di pervenire ad una nuova politica meridionalistica è eminentemente quello politico della creazione di una forza di pressione nel Sud capace di controbilanciare le spinte e le sollecitazioni che sull’apparato politico-buro- cratico riesce ad esercitare la struttura socio-finanziaria del Nord. -

Download the Sicilian Pdf Ebook by Mario Puzo

Download The Sicilian pdf ebook by Mario Puzo You're readind a review The Sicilian book. To get able to download The Sicilian you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this ebook on an database site. Book File Details: Original title: The Sicilian Paperback: Publisher: Arrow (2001) Language: English ISBN-10: 9780099580799 ISBN-13: 978-0099580799 ASIN: 0099580799 Product Dimensions:5.1 x 1 x 7.8 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 4284 kB Description: Michael Corleone is returning to the U.S. after the two-year exile to Sicily in which reader left him in The Godfather. But he is ordered to bring with him the young Sicilian bandit, Salvatore Guiliano, who is the unofficial ruler of northwestern Sicily. In his fight to make Sicilians free people, the young folk hero, based on the real-life Giuliano... Review: The Sicilian is a different storyline from The Godfather, but does intersect with Michael Corleone just before and just after his return to the US after that Sollozzo unpleasantness. There also is a surprising connection with Peter Clemenza. If you enjoyed The Godfather, then I believe you will enjoy The Sicilian.... Ebook File Tags: mario puzo pdf, michael corleone pdf, robin hood pdf, salvatore giuliano pdf, corleone family pdf, story line pdf, salvatore guiliano pdf, takes place pdf, good book pdf, better than the godfather pdf, great book pdf, main character pdf, read this book pdf, highly recommended pdf, turi giuliano pdf, sequel to the godfather pdf, puzo is probably best pdf, godfather series pdf, turi guiliano pdf, great story The Sicilian pdf book by Mario Puzo in pdf ebooks The Sicilian the sicilian book sicilian the fb2 sicilian the ebook the sicilian pdf The Sicilian I barely noticed any structural of sicilian issues. -

Law Enforcement Bulletin 104362-104363 U.S

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. February 1987~ Law Enforcement Bulletin 104362-104363 U.S. Department dt Justice Nationallnslllute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stat?d in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this ~ted material has been granted by FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the c~ht owner. February 19B7, Volume 56, Number 2 1 'The Sicilian Mafia and Its Impact on the United States Lay Sean M. McWeeney (" 0 cf 3b ~ 11 A Tradition of Excellence: The Southern Police Institute By Norman E. Pomrenke and B. Edward Campbell [P@OiJil~ @1I WO@W 15 UMen and Women Who Wear the Badge •.. That Others May Find Their Way" By Hon. Peter T. Fay [P[)'@@@ OO@O@~O@OU@ 18 An Automated News Media System By Roger Dickson 11®®@O @U®@@~ 22\lntrusive Body Searches: f,. Question of Reasonableness ~BY Kimberly A. Kingston, J.D. ((? 4-:3 63 31 Wanted by the FBI m] Law Enforcement Bulletin United States Department of Justice Published by the Office of The Cover: Federal Bureau of Investigation Congressional and Public Affairs, A media computer network system facilitates William M. Baker, Assistant Director the Interaction between a law enforcement agency Washington, DC 20535 and the local media by offering more-comprehen sive news coverage. -

A 2X52' Documentary by ANNE VERON

AB INTERNATIONAL DISTRIBUTION PRESENTS A 2X52’ documentary by ANNE VERON THE AMERICAN & SICILIAN MAFIAS : TWO FACTIONS THAT HAVE GIVEN CRIME A LEGENDARY STATUS A 2X52’ documentary by ANNE VERON SYNOPSIS NOTE OF INTENTION It has inspired the biggest directors. Be it the images of corpses strewn on This documentary in two episodes will One only needs to look at the photographs Plenty writers have helped immortalise the streets of New York or Palermo, of recount the history of the Cosa Nostra of Luciano Leggio when appearing at his it. The Cosa Nostra is the aristocracy of a disembowelled highway, blown up from its beginning in Sicily in the ‘50s until trial at the tribunal of Palermo in 1974: he organised crime. With its codes, its ho- by half a ton of explosives to get rid of these days. seems to have been set upon resembling nour-system, the omerta, the vendettas… a magistrate having become a thorn in Marlon Brando as Don Corleone with his The Cosa Nostra also encompasses all of the eye…The everyday drama of mob This story is told through testimonials of cigar, his heavy jaw and his arrogant de- the superlatives: the most mythical, ele- violence, the blood of the victims and repented mobsters, historians, magis- meanour The godfather of the movie was gant, violent, secret, the most popular… the tears of those who survived have trates, and journalists. We will depict their an image of how the mobsters liked to see the most fascinating. It’s the organisation forever left its print on the 20th century. -

David Seymour’S Album on the Fight Against Illiteracy in Calabria As a Tool of Mediatization: Material Traces of Editing and Visual Storytelling 263

They Did Not Stop at Eboli / Au-delà d’Eboli Edited by / Éditrices Giovanna Hendel, Carole Naggar & Karin Priem Appearances – Studies in Visual Research Edited by Tim Allender, Inés Dussel, Ian Grosvenor, Karin Priem Vol. 1 They Did Not Stop at Eboli: UNESCO and the Campaign against Illiteracy in a Reportage by David “Chim” Seymour and Texts by Carlo Levi (1950) Au-delà d’Eboli : l’UNESCO et la campagne contre l’analphabétisme, dans un reportage de David « Chim » Seymour et des textes de Carlo Levi (1950) Edited by / Éditrices Giovanna Hendel, Carole Naggar & Karin Priem Published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France, and Walter De Gruyter GmbH, Genthiner Strasse 13, D-10785 Berlin, Germany. © UNESCO and De Gruyter 2019 ISBN 978-3-11-065163-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-065559-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-065175-1 UNESCO ISBN 978-92-3-000084-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019951949 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbyncsa-en). -

Infoitaliaspagna 14 BIS.Indd

Infoitaliaspagna all’interno Rivista bimestrale gratuita n. quattordici anno 2 4 Camere di commercio italiane a Madrid web: www.infoitaliaspagna.com e Saragozza e-mail: [email protected] 6 Le nuove terminologie nella crisi dei mercati [email protected] finanziari Fax: + 34 –952 96 47 35 7 I piani adottati dai principali Governi europei mov. + 34 –670 46 35 04 8 Madrid come Milano per delinquenza giovanile Pubblicità: + 34 - 687 83 70 65 10 Intervista a Giuseppe Dossetti sul recupero Depósito legal MA -564 -2006 dei tossicodipendenti Impreso en los talleres Gráficas del Guadalhorce 14 Testimonianze da l’Europeo su chi tornava sconfitto dall’Argentina Direttore 17 Il rapporto 2008 sugli italiani nel mondo Patrizia Floder Reitter 18 Immagini del Vespucci in Spagna 23 Musica italiana in Andorra e a Santander Realizzazione grafica 24 Maschio e i suoi prodotti Prime Uve Graziella Tonucci 27 La Rubrica Legale 28 Valladolid e la medicina di Salerno 30 Arte e mostre 32 50 anni di Zecchino d’Oro 33 Il ponte di Calatrava a Venezia 34 Contatti utili in Spagna Se volete ricevere la rivista in abbonamento: + 34 –952 96 47 35 Foto Copertina: Ponte Santa Trinità a Firenze di Rita Kramer e Plaza de toros a Ronda di Ylebiann Cerchiamo collaboratori per la vendita Pag 12: Foto Gazzetta di Reggio di spazi pubblicitari. Pag 18 -19-20-21-22: Foto Domenico Recchia e Denis Maggi Per contatti: + 34 - 687 83 70 65 Pag. 23: Foto Dorte Passer Le altre foto: archivio Infoitaliaspagna e Internet l’editoriale di Patrizia Floder Reitter direttore La Borsa perde, il manager guadagna Quando una retribuzione diventa scandalosa.