Libraries Address the Challenges Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RECKONINGS Newsletter of the Department of Mathematical Sciences at the University of Delaware Chair’S Message in Memoriam John A

RECKONINGS Newsletter of the Department of Mathematical Sciences at the University of Delaware Chair’s Message In Memoriam John A. Pelesko Professor Wenbo V. Li, of the Department tute of Mathematical Statistics. The citation Dear Students, Alumni, Colleagues, and of Mathematical Sciences, died of a heart at- stated he was honored “for his distinguished Friends, tack on Saturday, January 26, near his home research in the theory of Gaussian processes This past year in Newark, Delaware, at the age of 49. Profes- and in using this theory to solve many impor- has been both an sor Li joined the University of Delaware di- tant problems in diverse areas of probability.’’ exciting year and rectly upon completing his Ph.D. at the Uni- Professor Li a sad year for versity of Wisconsin-Madison in 1992. He advised numerous the Department was promoted to Associate Professor in 1996 graduate students of Mathemati- and the rank of Professor in 2002. He held during his career cal Sciences. In an adjunct position with the Department of and was an active January, we very Electrical and Computer Engineering at UD, mentor for many unexpectedly an adjunct position with the Department of undergraduate lost Professor Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics research students. Wenbo V. Li to a heart attack. Professor at Delaware State University, and an adjunct Since joining the Li was an integral part of our department, position in the Department of Mathematics university, Profes- a tremendous friend and mentor to our at the Harbin Institute of Technology in Har- sor Li spearheaded students, and a world-renowned researcher bin, China. -

SPECTRUM Appreciation Day

TODAY’S EDITION See page 3 for information on Staff SPECTRUM Appreciation Day. VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY http://www.unirel.vt.edu/spectrum/ VOLUME 22 NUMBER 28 FRIDAY, APRIL 14, 2000 Presidential Installation to highlight activities An Open Letter to the Roselle to speak at Founders Day 2000 University Community By David Nutter Studies in 1981. He left Virginia Tech to become September 20. The highlight of this year’s Founders Day is always a special David Roselle, president of the president of the University of Kentucky. He has convocation will be the installation of Charles occasion, but this year it is unusually sig- University of Delaware and former provost been president of the University of Delaware Steger as Virginia Tech’s fifteenth president. nificant. As part of this year’s Founders of Virginia Tech, will be a guest speaker at since 1989. Steger will share with the university community Day activities, Charles Steger will be in- the Founders Day 2000 and Presidential The Founders Day/Presidential Installation his vision for the university’s future. stalled as the 15th president of Virginia Installation ceremony on Friday, April 28. convocation will begin at 3 p.m. in Burruss The ceremony will also be carried live on Polytechnic Institute and State Univer- Roselle served as Tech’s provost from auditorium. This year’s Founders Day marks a Channel 6 of the campus cable system and the sity. An opportunity to be part of such a 1983 until 1987. He came to Tech as a major departure from previous programs. The Channel 15 on the Blacksburg cable system. -

Alleged KA Sexual Assault Goes Unprosecuted

ln Section 2 In Sports An Associated Collegiate Press Sick kids Do Hens Four-Star All-American Newspaper make the get a medicinal grade? - page BlO education page B 1 I Non-profit Org. FREE U.S. Postage Pa1d FRIDAY Newark, DE Volume 122, Number 40 250 Student Center, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716 Permit No. 26 March 8, 1996 Alleged KA sexual assault goes unprosecuted conviction is wrong." are taken to the attorney general's before reporting an assault. such as the one previously alleged, Delay in reporting the incident cited as Speaking hypothetically , office to decide if there is enough "What does it tell men?" she we do believe that the attorney reason for dismissal; Sigma Kappa says Pederson said, if there is a evidence to prosecute, whereas the asked, her face flushed. "Nothing. If general's decision is a fair one, significant gap between the rape and university's judicial system is I were a guy, I would fear nothing.'' clearly made after carefully decision tells men to 'fear nothing' its reporting, you not only lose the designed to deal with non-criminal Interfraternity Council President investigating the matter in full." physical evidence, but it gives those code of conduct violations on Bill Werde disagreed , saying the When asked to respond to the BY KIM WALKER said. involved a chance to corroborate r------- campus. case conveys the opposite message. charge that Sigma Kappa was Managing Nt:ws Editor ··we did not find enough their stories. Dana Gereghty, "The message [the decision] sent punished while the former fraternity evidence that could lead to a The former Kappa Alpha Order Dean of Students Timothy F. -

Eastern Kentucky

~-- • ----;-r -- - () - -------------~.::.:...::.,.~~....:.~~..:::.;::..:;;~~::.......;.;..:.;__.;__..,.,'1/q/g1Oct. 3 1988 'rl ';)'/l-'fk :JO - I~ . 0 If .:i.o I ~ MSU Clip Sheet CCI- A rmpllq of ncent artlcla of lllterat to Morehad State Ualvcnlty MEDIA RELATIONS • MOREHEAD STATE UNIVERSITY • UPO BOX 1100 • MOREHEAD, KY 40351-1689 • 606-783-2030 ~EXINGTON,HERAlEl-LEAElER, ~NGTQN;,KY.,.·SAJURpA'!',·OCTQBEIH,,19811 rrn9iversrtres· ·. want~'·"oigger•,>•p1_e:, ~- ,., · -llte- fonnula· estab)ished a ra tional, formal basis for splitting the .·n·or~ratrer·~srrces state funding pie, she said. It is a .1 ' 1·. k~d- .,. ·- -.i:,...,.;o.,..,..:."";il Robert Bell,- chairtnan' ·of' Ken'~ !=Qmpl!,Jf, .5e! of components. used to ' By··oal'll181•r..'t1C V. • tucky Advocates for f!igher Edu~ calciiliife how much money each Her~td.-Le.a~er education write.r, - . ~ · tion, ,urgi;d, the .council tQ ~p up scliooLneeds 'to carry out its mis , -" IP 'corifrast to "the bi~, ~ its review quickly 311d begm ~ sfoil, coinpared ,with average fund, · divisive .l>irth· of formula ftm.dm~ paring for .a sJ:M.!(:ial l~la~v~.~- . ing at.1simitar:"schools in. other . s~·years ago, Kentucky's,,publi~ sion that Gov. Wallace I W11kirison stafes.,The-main component of the . universities have shown strong um has promised for, early next year. fo!ii;i~,is ~llment. : - ,' ty. as}he fonnula ~derg<M:5 its first Though Wilkinson has said he · :,·· The:·state• provides about 84 formal-review, offioals said;yester- does not plan to .put higher educa percent, of: the money needed to tion on the agenda;; Belr said 'the : daY;,~; real issue m: edu~tio~ \~ universities must be ready to push - fpn9;W,ej~rmu1a fullr. -

Class Notes 2010 by the Alumni Council, Please Visit Our Web Site At

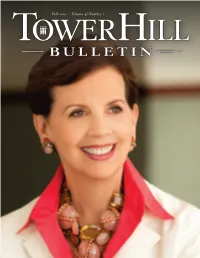

Update your e-mail address / towerhill.org / Go to Login and My Profile Stay Connected Fall 2010 Class Volume 47.Number Notes 1 2010 Tower Hill Bulletin Fall 2010 1 Aerial view of the Tower Hill School campus in May 2010 after the completion of the renovations of Walter S. Carpenter Field House in the upper left-hand corner. Headmaster Christopher D. Wheeler, Ph.D. in this issue... 2010-2011 Board of Trustees 2...............Headmaster letter David P. Roselle, Board Chair ..............Exceptional Alumni During Extraordinary Times Ellen J. Kullman ’74, Board Vice Chair 3 William H. Daiger, Jr., Board Treasurer 4..............Adrienne Arsht ’60: A Lifetime of Leadership Linda R. Boyden, Board Secretary in Business and Philanthropy Michael A. Acierno Theodore H. Ashford III Dr. Earl J. Ball III 8..............Mike Castle ’57 and Chris Coons ’81: A Delaware Election Robert W. Crowe, Jr. ’90 with National Consequences is a Green-White Contest Ben du Pont ’82 Charles M. Elson W. Whitfield Gardner ’81 10............Morgan Hendry ’01: NASA’s 21st Century Breed of Rocket Scientist Marc L. Greenberg ’81 Thomas D. Harvey 12............Casey Owens ’01: A New Generation Pierre duP. Hayward ’66 Michael P. Kelly ’75 of Americans with a Global Perspective Michelle Shepherd Matthew T. Twyman III ’88 14............Ron “Pathfinder” Strickland ’61: Lance L. Weaver Trail Developer, Dennis Zeleny Chief Advancement Officer Conservationist Julie R. Topkis-Scanlan and Author Editor, Communications Director Nancy B. Schuckert 16............Allison Barlow ’82: Associate Director of Advancement Cultivating a Future for Kim A. Murphy Native American Youth Director of Alumni Programs & Development Office Special Events Kathryn R. -

Who Is Stephanie Leveene?

In Sports In Sution2 An Associated Collegiate Press Four-Star All-American Newspaper Men thunder Straight up: to twelfth the particulars straight win of posture page 85 page B1 TUESDAY Police net Steady ... -~r--..,. Recruiter resigns, $22,000 takes national post ~l?r1r~g~,.:,v~or gets someone who cares about social and ;~~s!f/oncerns of students [in RISE).; in raid Fran.k A. Wells Jr. officially resigned as the director of the Resources to Insure An elected delegation of RISE studenti Successful Engineers (RISE) program was formed last semester to act as a liaisod Police from six Delaware Friday. between students and administration to Wells, who became director of the express concern about the future of thct departments conclude College of Engineering's minority program. recruitment program in 1987, announced his With the resignation of Wells members of two-month investigation resignation in early January and will begin the delegation said they want to be included his new job at the New York-based National in the search committee. By Sara H. Weiss Action Council for Minorities in President David P. Roselle said the Ciry News Edilor Engineering this month. university will miss Wells' leadership. Officers from six police departments "It's hard to be happy about the new job," "One of the beuer representations of across the state seized $22,000 worth of Wells said. "I'm still very concerned about African American students is in the College crack cocaine Thursday at the College who will come in and take over RISE." of Engineering and that's due to the Square Shopping Center which police Currently Ronald F. -

WOMEN and the MAA Women's Participation in the Mathematical Association of America Has Varied Over Time And, Depending On

WOMEN AND THE MAA Women’s participation in the Mathematical Association of America has varied over time and, depending on one’s point of view, has or has not changed at all over the organization’s first century. Given that it is difficult for one person to write about the entire history, we present here three separate articles dealing with this issue. As the reader will note, it is difficult to deal solely with the question of women and the MAA, given that the organization is closely tied to the American Mathematical Society and to other mathematics organizations. One could therefore think of these articles as dealing with the participation of women in the American mathematical community as a whole. The first article, “A Century of Women’s Participation in the MAA and Other Organizations” by Frances Rosamond, was written in 1991 for the book Winning Women Into Mathematics, edited by Patricia Clark Kenschaft and Sandra Keith for the MAA’s Committee on Participation of Women. The second article, “Women in MAA Leadership and in the American Mathematical Monthly” by Mary Gray and Lida Barrett, was written in 2011 at the request of the MAA Centennial History Subcommittee, while the final article, “Women in the MAA: A Personal Perspective” by Patricia Kenschaft, is a more personal memoir that was written in 2014 also at the request of the Subcommittee. There are three minor errors in the Rosamond article. First, it notes that the first two African- American women to receive the Ph.D. in mathematics were Evelyn Boyd Granville and Marjorie Lee Browne, both in 1949. -

UA3/8/1 President's Office-Meredith Correspondence / Subject File

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® WKU Archives Collection Inventories WKU Archives 2015 UA3/8/1 President's Office-Meredith Correspondence / Subject File WKU Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_ua_fin_aid Part of the African American Studies Commons, Construction Engineering Commons, Higher Education Administration Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Landscape Architecture Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation WKU Archives, "UA3/8/1 President's Office-Meredith Correspondence / Subject File" (2015). WKU Archives Collection Inventories. Paper 460. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_ua_fin_aid/460 This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in WKU Archives Collection Inventories by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Western Kentucky University UA3 President’s Office Series 8 Thomas Meredith Subseries 1 Correspondence / Subject File Contact information: WKU Archives 1906 College Heights Blvd.#11092 Bowling Green, KY 42101-1092 Phone: 270-745-4793 Email: [email protected] Home page: https://wku.edu/library/archive © 2019 WKU Archives, Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Administrative History: The president's office was created in 1906. The search for a new president began with Kern Alexander's resignation announcement on April 11, 1988. The Board of Regents elected Thomas Meredith as president August 5 and installed September 21, 1988. Under Meredith's leadership, the campus expanded with the purchase of the Bowling Green Center, creation the Institute of Economic Development and the implementation of the first strategic plan Western XXI. He also hired WKU's first female vice president, Barbara Burch. -

Celebrate Spring in a Symphony of Color and Sound

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE CELEBRATE SPRING IN A SYMPHONY April 15, 2015 OF COLOR AND SOUND WITH WINTERTHUR AND UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE CHORALE “Forgotten People and Beautiful Things” to be Performed April 26 in Copeland Hall WINTERTHUR, DELAWARE—Celebrate spring in a symphony of color and sound as The internationally renowned University of the internationally acclaimed University of Delaware Chorale performs Sunday, Delaware Chorale. Photo Courtesy of UD. April 26, in Winterthur’s Copeland Hall. The concert, “Forgotten People and Beautiful Things,” will feature moving selections based on folk songs from the MEDIA CONTACT Baltic states, which all but disappeared with the formation of the Union of Soviet th Liz Farrell Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.) in the early 20 century. [email protected] Phone: 302.888.4803 “Winterthur is delighted to host this springtime celebration of culture, heritage, Fax: 302.888.4950 and beauty with the exceptional talent of the University of Delaware Chorale,” said Dr. David Roselle, Director of Winterthur. Winterthur—known worldwide for its preeminent collection of American Dr. Paul Head, Unidel Professor and Director of Choral Studies at the University decorative arts, naturalistic gardens, of Delaware, said the program was designed to inspire, making it a perfect match and research library for the study of American art and material culture— for Winterthur, the former home of Henry Francis du Pont that features a world- offers a variety of tours, exhibitions, class museum, garden, and library. The garden’s azaleas will paint a brilliant programs, and activities throughout landscape of lavenders, pinks, corals, reds, and more. -

Dupont: the Explosives Era

DuPont: The Explosives Era DuPont Science & Discovery Raymond Loewy Hagley Museum and Library Annual Report 2002 DuPont: The Explosives Era In 2002, Hagley installed three exhibits; two that are permanent, and one DuPont Science & Discovery that received such acclaim that its stay was extended by seven months. Raymond Loewy 1 President’s Report Edward B. du Pont This was a year of transitions. DuPont; Howard E. Cosgrove, former Mostly notable was Glenn Porter’s CEO of Conectiv; Edie Hedlin, decision to retire as director and the Director of Archives for the Board of Trustees’ careful search for a Smithsonian Institution; Margaretta successor. Dr. Porter’s career at Hagley (Peg) Stabler, a du Pont family was outstanding, and the board member with long service at Hagley honored him appropriately for his and other area institutions; and me. I excellent stewardship and strong role have enjoyed serving on Hagley’s Tin building the library and archives to board and wish to thank my fellow its present renown. We wish him and board members for their faithful his wife Barbara Butler a happy and service to Hagley over the years. productive retirement in New Mexico. At year’s end, the board elected two In George L. Vogt, Glenn’s new members. These are Ann Copeland successor, the board found an Rose, granddaughter of Mr. and Mrs. experienced leader who has directed Lammot du Pont Copeland, who were the South Carolina Department of instrumental in creating and building Archives and History and, most Hagley Museum and Library; and Robert recently, the Wisconsin Historical V. -

Keepers Family to File Suit Against UD

An Associated Collegiate Press Four-Star All-American Newspaper TUESDAY March 11 , 1997 Volume 123 • THE • Number 39 Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage Paid Newark, DE 250 Student Center• University of Delaware • Newark, DE 19716 Pennit No. 26 Keepers family to file suit against UD BY KIM WALKER and servicers acted in ·'willful misconduct 1974 when he fe ll f rom the 17th fl oor force, said Arnold Jabin, the Keepers' Both Keepers and Slatkin were Mauagin'! Maga::ine Editor and reckless indifference'' by placing air window in the same building. fa mily lawyer. standin g on the radiator when they fell. A negligence suit was fil ed against the conditioning units under the windows and Experts hired by the estate of the ''The rooms s ho uld never have bee n R eports s ho wed Keepers· b lood university Thursday by the parents of a ins ta lling plated instead of tempered student, Howard Sla tkin, testified that if designed with those windows," he said . alcohol content was 0.096. In Delaware. a freshman who fe ll to his death from hi s glass. the glass had been tempered instead of The s uit said the university did not level of 0.10 is considered legal ly drunk. 13th-floor window in the Christiana East Robert A. Keepers Jr.. 19 , was trying plated . hi s acc ident would not have correct the hazards revea led in the Slatkin John Balaguer. who is representing the Tower 18 months ago. to co nnect with someone over e-mail occurred. -

SEC Record Book

2018-20192018-2019 RecordRecord BookBook The history of SEC Men’s & Women’s Golf, Men’s & Women’s Swimming & Diving, Women’s Equestrian, Men’s & Women’s Tennis, Men’s & Women’s Cross Country, Men’s & Women’s Indoor Track & Field, and Men’s & Women’s Outdoor Track & Field. www.SECsports.comwww.secsports.com IT JUST MEANS MORE. In February, the Southeastern Conference was named HÄUHSPZ[MVY[OL:WVY[Z)\ZPULZZ1V\YUHS»Z3LHN\LVM[OL [OL:,*LZ[HISPZOLK[^VHKKP[PVUHSPUUV]H[P]LWYVJLZZLZ[V Year, which recognizes excellence over the past year. The PTWYV]LVMÄJPH[PUN!HJVSSHIVYH[P]LYLWSH`Z`Z[LTPUTLU»Z SEC was the only college athletics conference named to a basketball and expanded experimental replay rules in list that included the Ladies Professional Golf Association baseball. 37.(4HQVY3LHN\L)HZLIHSS43)4HQVY3LHN\L :VJJLY43:HUK[OL5H[PVUHS)HZRL[IHSS(ZZVJPH[PVU ;OL:,*»ZSLHKLYZOPWILSPL]LZZ[YVUNS`[OH[PU[LYJVSSLNPH[L 5)( athletic conferences have an obligation to aid in Student- Scholars. Champions. Leaders. These are the pillars of the Athlete Development, both academically and athletically. Southeastern Conference, and together they represent the (ZZ\JO[OL:,*^HZ[OLÄYZ[JVUMLYLUJL[VLZ[HISPZOH vision for an 85-year-old intercollegiate athletic conference Student-Athlete Career Tour designed to prepare students for that experienced unparalleled success during the past year. professions after graduation, and this year the Conference Ranging from record-breaking accomplishments by student- ^LSJVTLKZ[\KLU[Z[V([SHU[HMVYHT\S[PKH`ZLYPLZVM H[OSL[LZHUKHKTPUPZ[YH[VYZ[VZPNUPÄJHU[NYV^[OPUTLKPH meetings and development. And the SEC has integrated its sponsorship, and branding, the SEC proved on every front student-athlete leadership councils into its annual meetings ^O`P[PZ:,*VUK[V5VUL [VNP]LP[Z`V\UNWLVWSLHNYLH[LY]VPJLPU[OLPYV^U collegiate experience.