Serious Infectious Complications Related to Extremity Cast/Splint Placement in Children B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kellie ID Emergencies.Pptx

4/24/11 ID Alert! recognizing rapidly fatal infections Susan M. Kellie, MD, MPH Professor of Medicine Division of Infectious Diseases, UNMSOM Hospital Epidemiologist UNMHSC and NMVAHCS Fever and…. Rash and altered mental status Rash Muscle pain Lymphadenopathy Hypotension Shortness of breath Recent travel Abdominal pain and diarrhea Case 1. The cross-country trucker A 30 year-old trucker driving from Oklahoma to California is hospitalized in Deming with fever and headache He is treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, but deteriorates with obtundation, low platelet count, and a centrifugal petechial rash and is transferred to UNMH 1 4/24/11 What is your diagnosis? What is the differential diagnosis of fever and headache with petechial rash? (in the US) Tickborne rickettsioses ◦ RMSF Bacteria ◦ Neisseria meningitidis Key diagnosis in this case: “doxycycline deficiency” Key vector-borne rickettsioses treated with doxycycline: RMSF-case-fatality 5-10% ◦ Fever, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, anorexia and headache ◦ Maculopapular rash progresses to petechial after 2-4 days of fever ◦ Occasionally without rash Human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis (HGA): case-fatality<1% Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME): case fatality 2-3% 2 4/24/11 Lab clues in rickettsioses The total white blood cell (WBC) count is typicallynormal in patients with RMSF, but increased numbers of immature bands are generally observed. Thrombocytopenia, mild elevations in hepatic transaminases, and hyponatremia might be observed with RMSF whereas leukopenia -

Cutaneous Melioidosis Dermatology Section

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18823.8463 Case Report Cutaneous Melioidosis Dermatology Section BASAVAPRABHU ACHAPPA1, DEEPAK MADI2, K. VIDYALAKSHMI3 ABSTRACT Melioidosis is an emerging infection in India. It usually presents as pneumonia. Melioidosis presenting as cutaneous lesions is uncommon. We present a case of cutaneous melioidosis from Southern India. Cutaneous melioidosis can present as an ulcer, pustule or as crusted erythematous lesions. A 22-year-old gentleman known case of diabetes mellitus was admitted in our hospital with an ulcer over the left thigh. Discharge from the ulcer grew Burkholderia pseudomallei. He was successfully treated with ceftazidime. Melioidosis must be considered in the differential diagnosis of nodular or ulcerative cutaneous lesion in a diabetic patient. Keywords: B. pseudomallei, Diabetes Mellitus, Skin ulcer CASE REPORT melioidosis is a rare entity. Cutaneous melioidosis may be primary A 22-year-old gentleman was admitted in our hospital with (presenting symptom is skin infection) or secondary (melioidosis complaints of an ulcer over the left thigh of seven days duration. at other sites in the body with incidental skin involvement) [3]. History of fever was present for four days. He also complained of There is limited published data from India documenting cutaneous pain in the thigh. The patient initially noticed a nodule on the left melioidosis. thigh which eventually progressed to form a discharging ulcer. He B. pseudomallei reside in soil and water [4]. Inoculation, inhalation was a known case of diabetes mellitus (type 1) on insulin. Clinical or ingestion of infected food or water are the modes of transmission examination revealed a 5cm× 5cm ulcer on the left thigh with [5]. -

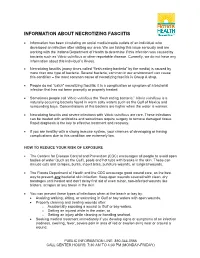

Necrotizing Fasciitis

INFORMATION ABOUT NECROTIZING FASCIITIS • Information has been circulating on social media/media outlets of an individual who developed an infection after visiting our area. We are taking this issue seriously and are working with the Indiana Department of Health to determine if this infection was caused by bacteria such as Vibrio vulnificus or other reportable disease. Currently, we do not have any information about this individual’s illness. • Necrotizing fasciitis (many times called “flesh eating bacteria” by the media) is caused by more than one type of bacteria. Several bacteria, common in our environment can cause this condition – the most common cause of necrotizing fasciitis is Group A strep. • People do not “catch” necrotizing fasciitis; it is a complication or symptom of a bacterial infection that has not been promptly or properly treated. • Sometimes people call Vibrio vulnificus the “flesh eating bacteria.” Vibrio vulnificus is a naturally occurring bacteria found in warm salty waters such as the Gulf of Mexico and surrounding bays. Concentrations of this bacteria are higher when the water is warmer. • Necrotizing fasciitis and severe infections with Vibrio vulnificus are rare. These infections can be treated with antibiotics and sometimes require surgery to remove damaged tissue. Rapid diagnosis is the key to effective treatment and recovery. • If you are healthy with a strong immune system, your chances of developing or having complications due to this condition are extremely low. HOW TO REDUCE YOUR RISK OF EXPOSURE • The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) encourages all people to avoid open bodies of water (such as the Gulf), pools and hot tubs with breaks in the skin. -

Staging of Necrotizing Fasciitis Based on the Evolving Cutaneous Features

ReportBlackwellOxford,IJDInternational0011-905945 UK Publishing Journal LtdLtd,of Dermatology 2006 StagingWang,Case report Wong, of necrotizing and Tay fascitis of necrotizing fasciitis based on the evolving cutaneous features Yi-Shi Wang, MBBS, MRCP, Chin-Ho Wong, MBBS, MRCS, and Yong-Kwang Tay, MBBS, FRCP From the Division of Dermatology, Changi Abstract General Hospital, Department of Plastic Background Necrotizing fasciitis is a severe soft-tissue infection characterized by a fulminant Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, course and high mortality. Early recognition is difficult as the disease is often clinically Singapore General Hospital, Singapore indistinguishable from cellulitis and other soft-tissue infections early in its evolution. Our aim was Correspondence to study the manifestations of the cutaneous signs of necrotizing fasciitis as the disease evolves. Yi-Shi Wang, MBBS, MRCP Methods This was a retrospective study on patients with necrotizing fasciitis at a single Division of Dermatology institution. Their charts were reviewed to document the daily cutaneous changes from the time Changi General Hospital of presentation (day 0) through to day 4 from presentation. 2 Simei Street 3 Singapore 529889 Results Twenty-two patients were identified. At initial assessment (day 0), almost all patients E-mail: [email protected] presented with erythema, tenderness, warm skin, and swelling. Blistering occurred in 41% of patients at presentation whereas late signs such as skin crepitus, necrosis, and anesthesia Presented at the European Academy of were infrequently seen (0–5%). As time elapsed, more patients had blistering (77% had blisters Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) 14th at day 4) and eventually the late signs of necrotizing fasciitis characterized by skin crepitus, Congress, London, October 12 to 16, 2005. -

Louisiana Morbidity Report

Louisiana Morbidity Report Office of Public Health - Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section P.O. Box 60630, New Orleans, LA 70160 - Phone: (504) 568-8313 www.dhh.louisiana.gov/LMR Infectious Disease Epidemiology Main Webpage BOBBY JINDAL KATHY KLIEBERT GOVERNOR www.infectiousdisease.dhh.louisiana.gov SECRETARY September - October, 2015 Volume 26, Number 5 Cutaneous Leishmaniasis - An Emerging Imported Infection Louisiana, 2015 Benjamin Munley, MPH; Angie Orellana, MPH; Christine Scott-Waldron, MSPH In the summer of 2015, a total of 3 cases of cutaneous leish- and the species was found to be L. panamensis, one of the 4 main maniasis, all male, were reported to the Department of Health species associated with progression to metastasized mucosal and Hospitals’ (DHH) Louisiana Office of Public Health (OPH). leishmaniasis in some instances. The first 2 cases to be reported were newly acquired, a 17-year- The third case to be reported in the summer of 2015 was from old male and his father, a 49-year-old male. Both had traveled to an Australian resident with an extensive travel history prior to Costa Rica approximately 2 months prior to their initial medical developing the skin lesion, although exact travel history could not consultation, and although they noticed bug bites after the trip, be confirmed. The case presented with a non-healing skin ulcer they did not notice any flies while traveling. It is not known less than 1 cm in diameter on his right leg. The ulcer had been where transmission of the parasite occurred while in Costa Rica, present for 18 months and had not previously been treated. -

Necrotizing Fasciitis Report of 39 Pediatric Cases

STUDY Necrotizing Fasciitis Report of 39 Pediatric Cases Antonio Fustes-Morales, MD; Pedro Gutierrez-Castrellon, MD; Carola Duran-Mckinster, MD; Luz Orozco-Covarrubias, MD; Lourdes Tamayo-Sanchez, MD; Ramon Ruiz-Maldonado, MD Background: Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a severe, Results: We examined 39 patients with NF (0.018% of life-threatening soft tissue infection. General features all hospitalized patients). Twenty-one patients (54%) were and risk factors for fatal outcome in children are not boys. Mean age was 4.4 years. Single lesions were seen in well known. 30 (77%) of patients, with 21(54%) in extremities. The most frequent preexisting condition was malnutrition in 14 pa- Objective: To characterize the features of NF in chil- tients (36%). The most frequent initiating factor was vari- dren and the risk factors for fatal outcome. cella in 13 patients (33%). Diagnosis of NF at admission was made in 11 patients (28%). Bacterial isolations in 24 Design: Retrospective, comparative, observational, and patients (62%) were polymicrobial in 17 (71%). Pseudo- longitudinal trial. monas aeruginosa was the most frequently isolated bacte- ria; gram-negative isolates, the most frequently associated Setting: Dermatology department of a tertiary care pe- bacteria. Complications were present in 33 patients (85%), diatric hospital. mortality in 7 (18%), and sequelae in 29 (91%) of 32 sur- viving patients. The significant risk factor related to a fatal Patients: All patients with clinical and/or histopatho- outcome was immunosuppression. logical diagnosis of NF seen from January 1, 1971, through December 31, 2000. Conclusions: Necrotizing fasciitis in children is fre- quently misdiagnosed, and several features differ from those Main Outcome Variables: Incidence, age, sex, num- of NF in adults. -

Reportable Diseases and Conditions by Year 2012-2016

County of San Diego Reportable Diseases and Conditions by Year 2012-2016 July 3, 2017 Disease/Condition and Case Inclusion Criteria (C, P, S)1 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Amebiasis2 C 64 34 62 36 5 Anaplasmosis/Ehrlichiosis C,P 1 0 0 0 0 Anthrax C,P 0 0 0 0 0 Babesiosis C,P 0 0 0 0 1 Botulism, Foodborne C 0 0 0 0 1 Botulism, Infant C 0 0 1 1 4 Botulism, Wound C 1 0 0 0 0 Brucellosis C,P 7 1 1 1 4 Campylobacteriosis C,P 728 589 848 649 786 Chicken Pox, Hospitalization or Death C,P 8 2 2 2 3 Chikungunya3 C,P 0 0 7 13 6 Chlamydia C,S 16,538 16,042 15,633 17,396 18,904 Cholera C 0 0 0 0 0 Ciguatera Fish Poisoning C 1 1 0 0 0 Coccidioidomycosis C 159 126 117 168 158 Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease C,P 0 6 6 7 4 Cryptococcosis C 1 0 1 1 0 Cryptosporidiosis C,P 30 24 36 24 35 Cyclosporiasis C,P 0 0 0 1 1 Cysticercosis C,P 0 2 5 0 1 Dengue Virus Infection C,P 11 12 6 17 23 Diptheria C,P 0 0 0 0 0 Domoic Acid Poisoning C 0 0 0 0 0 Encephalitis, Aseptic/Viral C 12 9 25 27 21 Encephalitis, Bacterial C 0 3 1 6 5 Encephalitis, Fungal C 0 0 0 0 3 Encephalitis, Parasitic C 1 0 0 1 0 Encephalitis, Other and Unknown C 27 32 25 46 42 Giardiasis C,P 242 264 262 314 397 Gonorrhea C,S 2,597 2,865 3,393 3,686 4,992 Haemophilus influenzae , Invasive Disease4 C,P 4 2 3 5 4 Hantavirus Infection C 1 0 0 0 0 Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome5 C,P 3 2 1 1 3 Hepatitis A, Acute C 38 40 15 21 26 Hepatitis B, Acute C 13 12 8 12 3 Hepatitis B, Chronic C,P 847 853 960 863 865 Hepatitis C, Acute6 C,P 4 2 0 2 1 Epidemiology and Immunization Services Branch 619-692-8499 www.sdepi.org Page -

June 08 Lyme Disease

DuPage County Health Department CD REVIEW Volume 4, No. 6 June 2008 The purpose of this two-page surveillance update is to promote the control and prevention of communicable disease (CD) by providing clinically relevant information and resources to healthcare professionals in DuPage County. 111 North County Farm Road For questions or to report a suspect or Wheaton, IL 60187 known case of Lyme disease, please call the (630) 682-7400 Under the Microscope DuPage County Health Department at www.dupagehealth.org Lyme Disease (630) 682-7400, ext. 7553. Linda Kurzawa Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and is transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected black-legged President, Board of Health tick (Ixodes scapularis, also known as the deer tick).1 The first clinical marker for the disease is usually a circular skin lesion (i.e., erythema migrans [EM]) that occurs in 70%-80% of patients at the site of a tick bite after an incubation period of 3-30 days.1 Maureen McHugh Typical symptoms include fever, headache, Executive Director fatigue, and EM. If left untreated, late manifes- Reported Cases of Lyme Disease by Month of Illness Onset tations can occur involving the joints (e.g., in DuPage County , 2003 - 2007 (n = 55) Rashmi Chugh, MD, MPH arthritis in one or a few joints), heart (e.g., acute 35 Medical Officer onset of atrioventricular conduction defects), 31 and nervous system (e.g., facial palsy).1 30 25 With approximately 20,000 new cases reported 20 Contact Information in the United States each year, Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the 15 9 Communicable Disease United States.2 Cases peak during summer 10 7 months, reflecting transmission by nymphal Number of Cases (630) 682-7400, ext. -

Adrenal Gland Hemorrhage in Patients with Fatal Bacterial Infections

Modern Pathology (2008) 21, 1113–1120 & 2008 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/08 $30.00 www.modernpathology.org Adrenal gland hemorrhage in patients with fatal bacterial infections Jeannette Guarner1, Christopher D Paddock2, Jeanine Bartlett2 and Sherif R Zaki2 1Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA and 2Infectious Diseases Pathology Branch, Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA A wide spectrum of adrenal gland pathology is seen during bacterial infections. Hemorrhage is particularly associated with meningococcemia, while abscesses have been described with several neonatal infections. We studied adrenal gland histopathology of 65 patients with bacterial infections documented in a variety of tissues by using immunohistochemistry. The infections diagnosed included Neisseria meningitidies, group A streptococcus, Rickettsia rickettsii, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Ehrlichia sp., Bacillus anthracis, Leptospira sp., Clostridium sp., Klebsiella sp., Legionella sp., Yersinia pestis, and Treponema pallidum. Bacteria were detected in the adrenal of 40 (61%) cases. Adrenal hemorrhage was present in 39 (60%) cases. Bacteria or bacterial antigens were observed in 31 (79%) of the cases with adrenal hemorrhage including 14 with N. meningitidis, four with R. rickettsii, four with S. pneumoniae, three with group A streptococcus, two with S. aureus, two with B. anthracis, one with T. pallidum, and one with Legionella sp. Bacterial antigens were observed in nine of 26 non-hemorrhagic adrenal glands that showed inflammatory foci (four cases), edema (two cases), congestion (two cases), or necrosis (one case). Hemorrhage is the most frequent adrenal gland pathology observed in fatal bacterial infections. -

Clinical Syndromes/Conditions with Required Level Or Precautions

Clinical Syndromes/Conditions with Required Level or Precautions This resource is an excerpt from the Best Practices for Routine Practices and Additional Precautions (Appendix N) and was reformatted for ease of use. For more information please contact Public Health Ontario’s Infection Prevention and Control Department at [email protected] or visit www.publichealthontario.ca Clinical Syndromes/Conditions with Required Level or Precautions This is an excerpt from the Best Practices for Routine Practices and Additional Precautions (Appendix N) Table of Contents ABSCESS DECUBITUS ULCER HAEMORRHAGIC FEVERS NOROVIRUS SMALLPOX OPHTHALMIA ADENOVIRUS INFECTION DENGUE HEPATITIS, VIRAL STAPHYLOCOCCAL DISEASE NEONATORUM AIDS DERMATITIS HERPANGINA PARAINFLUENZA VIRUS STREPTOCOCCAL DISEASE AMOEBIASIS DIARRHEA HERPES SIMPLEX PARATYPHOID FEVER STRONGYLOIDIASIS ANTHRAX DIPHTHERIA HISTOPLASMOSIS PARVOVIRUS B19 SYPHILIS ANTIBIOTIC-RESISTANT EBOLA VIRUS HIV PEDICULOSIS TAPEWORM DISEASE ORGANISMS (AROs) ARTHROPOD-BORNE ECHINOCOCCOSIS HOOKWORM DISEASE PERTUSSIS TETANUS VIRAL INFECTIONS ASCARIASIS ECHOVIRUS DISEASE HUMAN HERPESVIRUS PINWORMS TINEA ASPERGILLOSIS EHRLICHIOSIS IMPETIGO PLAGUE TOXOPLASMOSIS INFECTIOUS BABESIOSIS ENCEPHALITIS PLEURODYNIA TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME MONONUCLEOSIS ENTEROBACTERIACEAE- BLASTOMYCOSIS INFLUENZA PNEUMONIA TRENCHMOUTH RESISTANT BOTULISM ENTEROBIASIS KAWASAKI SYNDROME POLIOMYELITIS TRICHINOSIS PSEUDOMEMBRANOUS BRONCHITIS ENTEROCOLITIS LASSA FEVER TRICHOMONIASIS COLITIS -

Nebraska Reportable Disease Chart

Nebraska Reportable Diseases Title 173 Regulations Immediate Notification: Douglas Co. (402)444-7214 (after hrs 402- 444-7000) Lancaster Co (402) 441-8053 (after hrs 402-440-1817) All Other Counties 402-471-1983 Nebraska Public Health Laboratory 24/7 pager 402-888-5588 Labs- automated ELR Labs reporting manually Healthcare providers Updated 5/3/2017 Condition immediate within 7 days monthly immediate within 7 days monthly immediate within 7 days monthly Acinetobacter spp . (all species) x Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), as described in 173 NAC 1- 005.01C2 xxx Adenovirus x Aeromonas spp. x Amebae-associated infection (Acanthamoeba spp, Entamoeba histolytica , and Naegleria fowleri )xxx Anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) * ^ xx x Arboviral infections (including, but not limited to, West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, Western Equine encephalitis virus, Chikungunya virus, Rift Valley fever virus, Zika and Dengue virus) xxx Astrovirus x Babesiosis (Babesia species) x x x Botulism (Clostridium botulinum )* x x x Brucellosis (Brucella abortus^, B. melitensis^, and B. suis)*^ xx x Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) pseudomallei *^ xx x Campylobacteriosis (Campylobacter species )Do not forward to NPHL for banking or subtyping unless requested xxx Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (suspected or confirmed)^** xx x Carbon monoxide poisoning (Use break point for non-smokers) xxx Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi ) ± x x x Chikungunya virus xxx Citrobacter spp. x Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae x Chlamydia trachomatis infections (nonspecific urethritis, cervicitis, salpingitis, neonatal conjunctivitis, pneumonia)± xxx Cholera (Vibrio cholerae ) ^ x x x Clostridium difficile xxx Coccidiodomycosis (Coccidioides immitis/posadasii )xx x Coronavirus (Not MERS) x Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease [transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (14-3-3 protein from CSF or any laboratory analysis of brain tissue suggestive of CJD)] xxx Cryptosporidiosis (C. -

Healthy Brookline Volume

HEALTHY BROOKLINE VOLUME XVI Communicable Diseases in Brookline Brookline Department of Public Health 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by Janelle Mellor, MPH, with support from Natalie Miller, MPH, Barbara Westley, RN, and Lynne Karsten, MPH, under the direction of Alan Balsam, PhD, MPH, Director of Public Health and Human Services in Brookline. Thanks are also due to the Division Directors at the Brookline Department of Public Health for their support and input: Lynne Karsten, MPH Patrick Maloney, MPAH Mary Minott, LICSW Patricia Norling Gloria Rudisch, MD, MPH Dawn Sibor, MEd Barbara Westley, RN A special thanks to the Brookline Advisory Council on Public Health Bruce Cohen, PhD-Chair Roberta Gianfortoni, MA Milly Krakow, PhD Cheryl Lefman, MA Patricia Maher, RN/NP, MA/MA Anthony Schlaff, MD, MPH Support and data were also provided by: Susan Soliva, MPH, Massachusetts Department of Public Health The Healthy Brookline Chartbooks represent a partnership with a variety of funding sources: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Brigham & Women’s Hospital Children’s Hospital Farnsworth Trust Tufts Medical Center St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Brookline Community Foundation Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation Tufts Health Plan We thank them all for their generous support. Table of Contents Section 1: Communicable Disease Surveillance and Reporting .................................................................. 1 Surveillance and Reporting ......................................................................................................................