Necrotizing Fasciitis Report of 39 Pediatric Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kellie ID Emergencies.Pptx

4/24/11 ID Alert! recognizing rapidly fatal infections Susan M. Kellie, MD, MPH Professor of Medicine Division of Infectious Diseases, UNMSOM Hospital Epidemiologist UNMHSC and NMVAHCS Fever and…. Rash and altered mental status Rash Muscle pain Lymphadenopathy Hypotension Shortness of breath Recent travel Abdominal pain and diarrhea Case 1. The cross-country trucker A 30 year-old trucker driving from Oklahoma to California is hospitalized in Deming with fever and headache He is treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, but deteriorates with obtundation, low platelet count, and a centrifugal petechial rash and is transferred to UNMH 1 4/24/11 What is your diagnosis? What is the differential diagnosis of fever and headache with petechial rash? (in the US) Tickborne rickettsioses ◦ RMSF Bacteria ◦ Neisseria meningitidis Key diagnosis in this case: “doxycycline deficiency” Key vector-borne rickettsioses treated with doxycycline: RMSF-case-fatality 5-10% ◦ Fever, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, anorexia and headache ◦ Maculopapular rash progresses to petechial after 2-4 days of fever ◦ Occasionally without rash Human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis (HGA): case-fatality<1% Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME): case fatality 2-3% 2 4/24/11 Lab clues in rickettsioses The total white blood cell (WBC) count is typicallynormal in patients with RMSF, but increased numbers of immature bands are generally observed. Thrombocytopenia, mild elevations in hepatic transaminases, and hyponatremia might be observed with RMSF whereas leukopenia -

Cutaneous Melioidosis Dermatology Section

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18823.8463 Case Report Cutaneous Melioidosis Dermatology Section BASAVAPRABHU ACHAPPA1, DEEPAK MADI2, K. VIDYALAKSHMI3 ABSTRACT Melioidosis is an emerging infection in India. It usually presents as pneumonia. Melioidosis presenting as cutaneous lesions is uncommon. We present a case of cutaneous melioidosis from Southern India. Cutaneous melioidosis can present as an ulcer, pustule or as crusted erythematous lesions. A 22-year-old gentleman known case of diabetes mellitus was admitted in our hospital with an ulcer over the left thigh. Discharge from the ulcer grew Burkholderia pseudomallei. He was successfully treated with ceftazidime. Melioidosis must be considered in the differential diagnosis of nodular or ulcerative cutaneous lesion in a diabetic patient. Keywords: B. pseudomallei, Diabetes Mellitus, Skin ulcer CASE REPORT melioidosis is a rare entity. Cutaneous melioidosis may be primary A 22-year-old gentleman was admitted in our hospital with (presenting symptom is skin infection) or secondary (melioidosis complaints of an ulcer over the left thigh of seven days duration. at other sites in the body with incidental skin involvement) [3]. History of fever was present for four days. He also complained of There is limited published data from India documenting cutaneous pain in the thigh. The patient initially noticed a nodule on the left melioidosis. thigh which eventually progressed to form a discharging ulcer. He B. pseudomallei reside in soil and water [4]. Inoculation, inhalation was a known case of diabetes mellitus (type 1) on insulin. Clinical or ingestion of infected food or water are the modes of transmission examination revealed a 5cm× 5cm ulcer on the left thigh with [5]. -

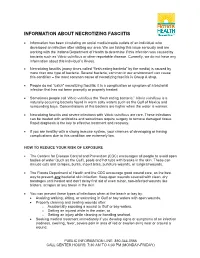

Necrotizing Fasciitis

INFORMATION ABOUT NECROTIZING FASCIITIS • Information has been circulating on social media/media outlets of an individual who developed an infection after visiting our area. We are taking this issue seriously and are working with the Indiana Department of Health to determine if this infection was caused by bacteria such as Vibrio vulnificus or other reportable disease. Currently, we do not have any information about this individual’s illness. • Necrotizing fasciitis (many times called “flesh eating bacteria” by the media) is caused by more than one type of bacteria. Several bacteria, common in our environment can cause this condition – the most common cause of necrotizing fasciitis is Group A strep. • People do not “catch” necrotizing fasciitis; it is a complication or symptom of a bacterial infection that has not been promptly or properly treated. • Sometimes people call Vibrio vulnificus the “flesh eating bacteria.” Vibrio vulnificus is a naturally occurring bacteria found in warm salty waters such as the Gulf of Mexico and surrounding bays. Concentrations of this bacteria are higher when the water is warmer. • Necrotizing fasciitis and severe infections with Vibrio vulnificus are rare. These infections can be treated with antibiotics and sometimes require surgery to remove damaged tissue. Rapid diagnosis is the key to effective treatment and recovery. • If you are healthy with a strong immune system, your chances of developing or having complications due to this condition are extremely low. HOW TO REDUCE YOUR RISK OF EXPOSURE • The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) encourages all people to avoid open bodies of water (such as the Gulf), pools and hot tubs with breaks in the skin. -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Staging of Necrotizing Fasciitis Based on the Evolving Cutaneous Features

ReportBlackwellOxford,IJDInternational0011-905945 UK Publishing Journal LtdLtd,of Dermatology 2006 StagingWang,Case report Wong, of necrotizing and Tay fascitis of necrotizing fasciitis based on the evolving cutaneous features Yi-Shi Wang, MBBS, MRCP, Chin-Ho Wong, MBBS, MRCS, and Yong-Kwang Tay, MBBS, FRCP From the Division of Dermatology, Changi Abstract General Hospital, Department of Plastic Background Necrotizing fasciitis is a severe soft-tissue infection characterized by a fulminant Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, course and high mortality. Early recognition is difficult as the disease is often clinically Singapore General Hospital, Singapore indistinguishable from cellulitis and other soft-tissue infections early in its evolution. Our aim was Correspondence to study the manifestations of the cutaneous signs of necrotizing fasciitis as the disease evolves. Yi-Shi Wang, MBBS, MRCP Methods This was a retrospective study on patients with necrotizing fasciitis at a single Division of Dermatology institution. Their charts were reviewed to document the daily cutaneous changes from the time Changi General Hospital of presentation (day 0) through to day 4 from presentation. 2 Simei Street 3 Singapore 529889 Results Twenty-two patients were identified. At initial assessment (day 0), almost all patients E-mail: [email protected] presented with erythema, tenderness, warm skin, and swelling. Blistering occurred in 41% of patients at presentation whereas late signs such as skin crepitus, necrosis, and anesthesia Presented at the European Academy of were infrequently seen (0–5%). As time elapsed, more patients had blistering (77% had blisters Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) 14th at day 4) and eventually the late signs of necrotizing fasciitis characterized by skin crepitus, Congress, London, October 12 to 16, 2005. -

Bacterial Infections Diseases Picture Cause Basic Lesion

page: 117 Chapter 6: alphabetical Bacterial infections diseases picture cause basic lesion search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Impetigo page: 118 6.1 Impetigo alphabetical Bullous impetigo Bullae with cloudy contents, often surrounded by an erythematous halo. These bullae rupture easily picture and are rapidly replaced by extensive crusty patches. Bullous impetigo is classically caused by Staphylococcus aureus. cause basic lesion Basic Lesions: Bullae; Crusts Causes: Infection search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Impetigo page: 119 alphabetical Non-bullous impetigo Erythematous patches covered by a yellowish crust. Lesions are most frequently around the mouth. picture Lesions around the nose are very characteristic and require prolonged treatment. ß-Haemolytic streptococcus is cause most frequently found in this type of impetigo. basic lesion Basic Lesions: Erythematous Macule; Crusts Causes: Infection search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Ecthyma page: 120 6.2 Ecthyma alphabetical Slow and gradually deepening ulceration surmounted by a thick crust. The usual site of ecthyma are the legs. After healing there is a permanent scar. The pathogen is picture often a streptococcus. Ecthyma is very common in tropical countries. cause basic lesion Basic Lesions: Crusts; Ulcers Causes: Infection search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Folliculitis page: 121 6.3 Folliculitis -

Pseudomonas Skin Infection Clinical Features, Epidemiology, and Management

Am J Clin Dermatol 2011; 12 (3): 157-169 THERAPY IN PRACTICE 1175-0561/11/0003-0157/$49.95/0 ª 2011 Adis Data Information BV. All rights reserved. Pseudomonas Skin Infection Clinical Features, Epidemiology, and Management Douglas C. Wu,1 Wilson W. Chan,2 Andrei I. Metelitsa,1 Loretta Fiorillo1 and Andrew N. Lin1 1 Division of Dermatology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 2 Department of Laboratory Medicine, Medical Microbiology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Contents Abstract........................................................................................................... 158 1. Introduction . 158 1.1 Microbiology . 158 1.2 Pathogenesis . 158 1.3 Epidemiology: The Rise of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ............................................................. 158 2. Cutaneous Manifestations of P. aeruginosa Infection. 159 2.1 Primary P. aeruginosa Infections of the Skin . 159 2.1.1 Green Nail Syndrome. 159 2.1.2 Interdigital Infections . 159 2.1.3 Folliculitis . 159 2.1.4 Infections of the Ear . 160 2.2 P. aeruginosa Bacteremia . 160 2.2.1 Subcutaneous Nodules as a Sign of P. aeruginosa Bacteremia . 161 2.2.2 Ecthyma Gangrenosum . 161 2.2.3 Severe Skin and Soft Tissue Infection (SSTI): Gangrenous Cellulitis and Necrotizing Fasciitis. 161 2.2.4 Burn Wounds . 162 2.2.5 AIDS................................................................................................. 162 2.3 Other Cutaneous Manifestations . 162 3. Antimicrobial Therapy: General Principles . 163 3.1 The Development of Antibacterial Resistance . 163 3.2 Anti-Pseudomonal Agents . 163 3.3 Monotherapy versus Combination Therapy . 164 4. Antimicrobial Therapy: Specific Syndromes . 164 4.1 Primary P. aeruginosa Infections of the Skin . 164 4.1.1 Green Nail Syndrome. 164 4.1.2 Interdigital Infections . 165 4.1.3 Folliculitis . -

Louisiana Morbidity Report

Louisiana Morbidity Report Office of Public Health - Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section P.O. Box 60630, New Orleans, LA 70160 - Phone: (504) 568-8313 www.dhh.louisiana.gov/LMR Infectious Disease Epidemiology Main Webpage BOBBY JINDAL KATHY KLIEBERT GOVERNOR www.infectiousdisease.dhh.louisiana.gov SECRETARY September - October, 2015 Volume 26, Number 5 Cutaneous Leishmaniasis - An Emerging Imported Infection Louisiana, 2015 Benjamin Munley, MPH; Angie Orellana, MPH; Christine Scott-Waldron, MSPH In the summer of 2015, a total of 3 cases of cutaneous leish- and the species was found to be L. panamensis, one of the 4 main maniasis, all male, were reported to the Department of Health species associated with progression to metastasized mucosal and Hospitals’ (DHH) Louisiana Office of Public Health (OPH). leishmaniasis in some instances. The first 2 cases to be reported were newly acquired, a 17-year- The third case to be reported in the summer of 2015 was from old male and his father, a 49-year-old male. Both had traveled to an Australian resident with an extensive travel history prior to Costa Rica approximately 2 months prior to their initial medical developing the skin lesion, although exact travel history could not consultation, and although they noticed bug bites after the trip, be confirmed. The case presented with a non-healing skin ulcer they did not notice any flies while traveling. It is not known less than 1 cm in diameter on his right leg. The ulcer had been where transmission of the parasite occurred while in Costa Rica, present for 18 months and had not previously been treated. -

Skin Disease and Disorders

Sports Dermatology Robert Kiningham, MD, FACSM Department of Family Medicine University of Michigan Health System Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest ◼ None Goals and Objectives ◼ Review skin infections common in athletes ◼ Establish a logical treatment approach to skin infections ◼ Discuss ways to decrease the risk of athlete’s acquiring and spreading skin infections ◼ Discuss disqualification and return-to-play criteria for athletes with skin infections ◼ Recognize and treat non-infectious skin conditions in athletes Skin Infections in Athletes ◼ Bacterial ◼ Herpetic ◼ Fungal Skin Infections in Athletes ◼ Very common – most common cause of practice-loss time in wrestlers ◼ Athletes are susceptible because: – Prone to skin breakdown (abrasions, cuts) – Warm, moist environment – Close contacts Cases 1 -3 ◼ 21 year old male football player with 4 day h/o left axillary pain and tenderness. Two days ago he noticed a tender “bump” that is getting bigger and more tender. ◼ 16 year old football player with 3 day h/o mildly tender lesions on chin. Started as a single lesion, but now has “spread”. Over the past day the lesions have developed a dark yellowish crust. ◼ 19 year old wrestler with a 3 day h/o lesions on right side of face. Noticed “tingling” 4 days ago, small fluid filled lesions then appeared that have now started to crust over. Skin Infections Bacterial Skin Infections ◼ Cellulitis ◼ Erysipelas ◼ Impetigo ◼ Furunculosis ◼ Folliculitis ◼ Paronychea Cellulitis Cellulitis ◼ Diffuse infection of connective tissue with severe inflammation of dermal and subcutaneous layers of the skin – Triad of erythema, edema, and warmth in the absence of underlying foci ◼ S. aureus or S. pyogenes Erysipelas Erysipelas ◼ Superficial infection of the dermis ◼ Distinguished from cellulitis by the intracutaneous edema that produces palpable margins of the skin. -

Z:\My Documents\WPDOCS\IACUC

ZOONOTIC DISEASES OF LABORATORY, AGRICULTURAL, AND WILDLIFE ANIMALS July, 2007 Michael S. Rand, DVM, DACLAM University Animal Care University of Arizona PO Box 245092 Tucson, AZ 85724-5092 (520) 626-6705 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ahsc.arizona.edu/uac Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Amebiasis ............................................................................................................................................... 5 B Virus .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Balantidiasis ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Brucellosis ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Campylobacteriosis ................................................................................................................................ 7 Capnocytophagosis ............................................................................................................................ 8 Cat Scratch Disease ............................................................................................................................... 9 Chlamydiosis ..................................................................................................................................... -

Reportable Diseases and Conditions by Year 2012-2016

County of San Diego Reportable Diseases and Conditions by Year 2012-2016 July 3, 2017 Disease/Condition and Case Inclusion Criteria (C, P, S)1 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Amebiasis2 C 64 34 62 36 5 Anaplasmosis/Ehrlichiosis C,P 1 0 0 0 0 Anthrax C,P 0 0 0 0 0 Babesiosis C,P 0 0 0 0 1 Botulism, Foodborne C 0 0 0 0 1 Botulism, Infant C 0 0 1 1 4 Botulism, Wound C 1 0 0 0 0 Brucellosis C,P 7 1 1 1 4 Campylobacteriosis C,P 728 589 848 649 786 Chicken Pox, Hospitalization or Death C,P 8 2 2 2 3 Chikungunya3 C,P 0 0 7 13 6 Chlamydia C,S 16,538 16,042 15,633 17,396 18,904 Cholera C 0 0 0 0 0 Ciguatera Fish Poisoning C 1 1 0 0 0 Coccidioidomycosis C 159 126 117 168 158 Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease C,P 0 6 6 7 4 Cryptococcosis C 1 0 1 1 0 Cryptosporidiosis C,P 30 24 36 24 35 Cyclosporiasis C,P 0 0 0 1 1 Cysticercosis C,P 0 2 5 0 1 Dengue Virus Infection C,P 11 12 6 17 23 Diptheria C,P 0 0 0 0 0 Domoic Acid Poisoning C 0 0 0 0 0 Encephalitis, Aseptic/Viral C 12 9 25 27 21 Encephalitis, Bacterial C 0 3 1 6 5 Encephalitis, Fungal C 0 0 0 0 3 Encephalitis, Parasitic C 1 0 0 1 0 Encephalitis, Other and Unknown C 27 32 25 46 42 Giardiasis C,P 242 264 262 314 397 Gonorrhea C,S 2,597 2,865 3,393 3,686 4,992 Haemophilus influenzae , Invasive Disease4 C,P 4 2 3 5 4 Hantavirus Infection C 1 0 0 0 0 Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome5 C,P 3 2 1 1 3 Hepatitis A, Acute C 38 40 15 21 26 Hepatitis B, Acute C 13 12 8 12 3 Hepatitis B, Chronic C,P 847 853 960 863 865 Hepatitis C, Acute6 C,P 4 2 0 2 1 Epidemiology and Immunization Services Branch 619-692-8499 www.sdepi.org Page -

Skin and Soft Ssue Infec On

Skin and so* +ssue infec+on N.Nuntachit MD. Non purulent SSTI • Impe+go, ecthyma • Celluli+s, Erysipelas • Erysipeloid • Necro+zing infec+on • Etc eg Glanders, bubonic plaque Purulent SSTI • Furuncle • Carbuncle • Abscess • Etc eg Tularemia SSTI severity • Purulent SSTI – Mild infec+on: I&D is indicated – Moderate: + systemic signs – Severe: failed I&D + ABT, systemic signs • Non purulent SSTI – Mild infec+on: no focus of purulence – Moderate: + systemic signs – Severe: failed oral ABTs, systemic signs, compromised, signs of deeper infecon Impe+go, Ecthyma • S.aureus or Beta hemoly+c streptococci • Difference – Depth – Scar • ABT should be ac+ve against both S. aureus and streptococci • Systemic therapy preferred – Pts with numerous lesions – Outbreaks Treatment An#bio#c Dosage Comment Dicloxacillin 250 mg po qid Cephalexin 250 mg po qid Erythromycin 250 mg po qid Some strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes may be resistant Clindamycin 300-400 mg po qid Amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg po bid Retapamulin ointment Apply lesions bid For paents with limited number of lesions Mupirocin ointment Apply lesions bid For paents with limited number of lesions Celluli+s, Erysipelas • Erysipelas • Cellulis – Upper dermis – Deeper dermis, – Delineated border subcutaneous fat – May be refer to celluli+s – No clear border of face • Areas of erythema, swelling, tenderness, and warmth, some+mes accompanied by lymphangi+s and inflammaon of the regional lymph nodes. The skin surface may resemble an orange peel (peau d’orange) Celluli+s,