Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relazione Analisi Corretta

111 PREMESSA 3 1.11.11.1 RIFERIMENTI ALL’INCARICO 3 1.21.21.2 RIFERIMENTI NORMATIVI 4 1.31.31.3 VALIDITÀ DEL PIANO EEE OBIETTIVI GENERALI 5 222 ANALISI 7 2.12.12.1 METODOLOGIA 7 2.1.1 ANALISI DEL CONTESTO TERRITORIALE 8 2.1.2 ANALISI FORESTALE E RILIEVI IN CAMPO 9 2.1.3 INDIVIDUAZIONE DELLE STRATEGIE MEDIANTE ANALISI SWOT 10 333 DATI SINTETICI DI PIPIANOANO 12 444 ASPETTI SOCIOECONOMISOCIOECONOMICICICICI 13 4.14.14.1 DINAMICA DELLA POPOLAZIONE 13 4.24.24.2 ILILIL SISTEMA SOCIOSOCIO----ECONOMICOECONOMICO EEE LELELE DINAMICHE DEL MERCATO DEL LAVOLAVORORORORO 14 4.34.34.3 COMPARTO TURISTICO 14 4.3.1 IL SISTEMA TURISTICO DELLE OROBIE BERGAMASCHE 15 4.44.44.4 COMPARTO AGRICOLO 16 4.54.54.5 FILIERA FORESTAFORESTA----LEGNOLEGNO EEE FILIERE CONNESSE 19 4.5.1 GENERALITÀ DEL SETTORE 19 4.5.2 DENUNCE TAGLIO BOSCO : CHI TAGLIA E QUANTO . 22 4.64.64.6 TRASFORMAZIONI DEL BOSCO PREGRESSE EDEDED INTERVENTI COMPENSATIVI 30 555 ASPETTI TERRITORIALI E AMBIENTALI 33 5.15.15.1 INQUADRAMENTO GEOGRAFICO 33 5.25.25.2 INQUADRAMENTO AMMINISTRATIVO 35 5.35.35.3 INQUADRAMENTO CLIMATOLOGICO 36 5.45.45.4 INQUADRAMENTO GEOMORFOLOGICO, LITOLOGICO EEE CLIVOMETRICLIVOMETRICOCOCOCO 44 5.55.55.5 PAI, RISCHIO IDROGEOLOGICO EEE DINAMICHE DISSESTIVE INININ ATTO 47 PIF Valle Brembana inferiore – Bozza proposta di piano Relazione fase di analisi 666 PIANIFICAZIONE TERRITERRITORIALETORIALE SOVRAORDINATSOVRAORDINATAA E COMPLEMENTACOMPLEMENTARERERERE 49 6.16.16.1 ILILIL PIANO TERRITORIALE DIDIDI COORDINAMENTO PROVINCIALE 49 6.26.26.2 ILILIL PIANO FAUNISTICOFAUNISTICO----VENATORIOVENATORIO -

A Hydrographic Approach to the Alps

• • 330 A HYDROGRAPHIC APPROACH TO THE ALPS A HYDROGRAPHIC APPROACH TO THE ALPS • • • PART III BY E. CODDINGTON SUB-SYSTEMS OF (ADRIATIC .W. NORTH SEA] BASIC SYSTEM ' • HIS is the only Basic System whose watershed does not penetrate beyond the Alps, so it is immaterial whether it be traced·from W. to E. as [Adriatic .w. North Sea], or from E. toW. as [North Sea . w. Adriatic]. The Basic Watershed, which also answers to the title [Po ~ w. Rhine], is short arid for purposes of practical convenience scarcely requires subdivision, but the distinction between the Aar basin (actually Reuss, and Limmat) and that of the Rhine itself, is of too great significance to be overlooked, to say nothing of the magnitude and importance of the Major Branch System involved. This gives two Basic Sections of very unequal dimensions, but the ., Alps being of natural origin cannot be expected to fall into more or less equal com partments. Two rather less unbalanced sections could be obtained by differentiating Ticino.- and Adda-drainage on the Po-side, but this would exhibit both hydrographic and Alpine inferiority. (1) BASIC SECTION SYSTEM (Po .W. AAR]. This System happens to be synonymous with (Po .w. Reuss] and with [Ticino .w. Reuss]. · The Watershed From .Wyttenwasserstock (E) the Basic Watershed runs generally E.N.E. to the Hiihnerstock, Passo Cavanna, Pizzo Luceridro, St. Gotthard Pass, and Pizzo Centrale; thence S.E. to the Giubing and Unteralp Pass, and finally E.N.E., to end in the otherwise not very notable Piz Alv .1 Offshoot in the Po ( Ticino) basin A spur runs W.S.W. -

L'alpeggio Nelle Alpi Lombarde Tra Passato E Presente

L’ alpeggio nelle Alpi lombarde tra passato e presente di Michele Corti* Sommario 1. Introduzione: tra presente e passato 2. Il dualismo delle voci “alpe” e “malga” in Lombardia (alcuni aspetti linguistici) 3. Tipologie insediative e strutture edilizie d’alpeggio 4. La migrazione alpina (spostamenti tra una valle e l’altra) 5. Proprietà delle alpi: aspetti storici 6. I conflitti sui diritti d’alpeggio 7. Forme di gestione e modalità di fruizione dei diritti di pascolo nel medioevo e nell’età moderna (statuti) 8. Tra XIX e XX secolo: le conseguenze sul sistema d’alpeggio della rottura di equilibri economici e demografici e dei cambiamenti politici 9. Spirito individualistico e spirito associativo nella gestione degli alpeggi sino alla metà del XX secolo 10. Credenze, leggende, riti 11. Gli sviluppi dalla seconda metà del XX secolo ad oggi: passato e presente Bibliografia * una versione del presente saggio è stata pubblicata in: SM Annali di San Michele, vol. 17, 2004, pp. 31- 155 1. Introduzione: tra presente e passato Nell’immaginario turistico le alpi pascolive sono maggiormente associate ad altre regioni dell’Arco Alpino piuttosto che alla Lombardia; eppure, secondo stime dei servizi veterinari regionali, riferite al 20011, ben il 46% di esse si trovavano in Lombardia, che ne conta ben 612, contro 409 di Piemonte e Valle d’Aosta e 306 del Triveneto. Secondo le stesse fonti, in Lombardia si trasforma il 30% di tutto il latte prodotto e lavorato nelle alpi pascolive dell’Arco Alpino, ma è caricato solo il 13% di tutti i capi bovini alpeggiati. -

PIANO DI GESTIONE DEL SIC IT2040028 “Valle Del Bitto Di Albaredo” - PIANO PILOTA

PIANO DI GESTIONE DEL SIC IT2040028 “Valle del Bitto di Albaredo” - PIANO PILOTA - Sondrio, anno 2010 Foto copertina: prati montani da fieno e mosaico ambientale nei pressi di Loc. Madonna delle Grazie Autore: G. Parolo 2 AUTORI Supervisione: Dott. Claudio La Ragione (Direttore Parco delle Orobie Valtellinesi, Ente Gestore del SIC). Coordinamento e responsabilità scientifica: Dr. Gilberto Parolo e Prof. Graziano Rossi (Dipartimento di Ecologia del Territorio - Università di Pavia). Quadro conoscitivo, pianificazione e aspetti socio-economici: Dott.ssa Marzia Fioroni (Sondrio). Fauna: Dott. Enrico Bassi (Bormio, SO). Flora e habitat: Dott. Franco Angelini (Delebio, SO), Dr. Gilberto Parolo (Università di Pavia). Gestione partecipata: Dott.ssa Chiara Pirovano (WWF, Milano). RINGRAZIAMENTI Ringraziamo sentitamente tutte le persone che hanno contribuito alla realizzazione di questo piano di gestione, fornendo materiali ed informazioni utili, in particolare il sindaco di Albaredo per San Marco, Sig.ra Antonella Furlini, e il suo Assessore Albertino Del Nero, e il Sindaco di Bema, Sig. Giacomino Lanza. Si ringraziano sentitamente il Dott. Paride Dioli (Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Morbegno) e il Dott. Nicola Pilon (Milano) senza il cui aiuto, prezioso e disinteressato, non sarebbe stato possibile presentare un quadro preliminare dell’entomofauna presente. Un grazie particolare va ai Signori Giovanni Pelucchi e Albino Caroli del Comprensorio Alpino di Morbegno che hanno collaborato significativamente sia fornendo le segnalazioni inerenti i galliformi sia altre segnalazioni relative ad altre specie faunistiche. Grazie anche agli Agenti del Corpo di Polizia Provinciale di Sondrio: in particolare si ringraziano Ettore Mozzetti, Antonio Ronconi e Fausto Luciani per la disponibilità dimostrata durante i sopralluoghi e per le inedite segnalazioni fornite. -

Asset: Accordi Per Lo Sviluppo Socio Economico Dei Territori Montani

ASSET: ACCORDI PER LO SVILUPPO SOCIO ECONOMICO DEI TERRITORI MONTANI SCHEDA DI SINTESI DEL PROGETTO Soggetto Capofila Comune di Olmo al Brembo (Denominazione, Dati ana- Sindaco Carmelo Goglio grafici del rappresentante le- Via Roma 12 - 24010 Olmo al Brembo BG gale) Email: [email protected] Referente Operativo Funzionario Incaricato: Mara Monaci (Servizio Ragioneria) del Capofila Tel.: 0345 87021 - Email: [email protected] Consulente di progetto: Oliviero Cresta (TradeLab) (nome e contatto tele- Tel.: 347 8944314 – Email: [email protected] fonico/e-mail) Denominazione del Sapori in Alta Quota Progetto Obiettivi e finalità del Obiettivi del progetto progetto 1. Favorire il mantenimento del tessuto commerciale e turistico − Descrizione degli della zona di intervento mediante la promozione dell’integra- obiettivi del progetto zione tra commercio, turismo e valorizzazione delle produzioni − Descrizione del con- agroalimentari. testo (corredato dai 2. Favorire la resilienza (capacità di resistere e adattarsi agli shock dati) esterni) della comunità locale, sfruttando gli asset a disposi- − Localizzazione geo- zione. grafica 3. Contrastare la desertificazione commerciale favorendo la na- − Descrizione sintetica scita di nuove imprese, specialmente giovanili, e il ricambio ge- degli interventi previ- nerazionale che mantiene i giovani sul territorio, frenandone sti l’emigrazione verso altre aree. Localizzazione geografica e territorio di riferimento Il progetto “Sapori ad alta quota” riguarda 16 comuni dell’Alta Valle -

Quaderni Brembani 19 28/10/20 09.34 Pagina 1

Quaderni Brembani 19 28/10/20 09.34 Pagina 1 QUADERNI BREMBANI19 CORPONOVE Quaderni Brembani 19 28/10/20 09.34 Pagina 2 QUADERNI BREMBANI Bollettino del Centro Storico Culturale Valle Brembana “Felice Riceputi” Viale della Vittoria, 49, San Pellegrino Terme (BG) Tel. Presidente: 366-4532151; Segreteria: 366-4532152 www.culturabrembana.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Cultura Brembana Coordinamento editoriale: Arrigo Arrigoni, Tarcisio Bottani IN COPERTINA: Boscaioli dell’Alta Valle Brembana con attrezzo tirafili (fine XIX - inizio XX sec). Dalla mostra “Il fotografo ritrovato, la Valle Brembana, e non solo, nelle fotografie di Andrea Milesi di Ornica (1867-1938)” Corponove BG - novembre 2020 Quaderni Brembani 19 28/10/20 09.34 Pagina 3 CENTRO STORICO CULTURALE VALLE BREMBANA “Felice Riceputi” QUADERNI BREMBANI19 Anno 2021 Quaderni Brembani 19 28/10/20 09.34 Pagina 4 CENTRO STORICO CULTURALE VALLE BREMBANA “FELICE RICEPUTI” Consiglio Direttivo Presidente: Tarcisio Bottani Vice Presidente: Simona Gentili Consiglieri: Giacomo Calvi Erika Locatelli Mara Milesi Marco Mosca Antonella Pesenti Comitato dei Garanti: Lorenzo Cherubelli Carletto Forchini Giuseppe Gentili Collegio dei Revisori dei Conti: Raffaella Del Ponte Pier Luigi Ghisalberti Vincenzo Rombolà Segretario: GianMario Arizzi Quaderni Brembani 19 28/10/20 09.34 Pagina 5 Quaderni Brembani 19 Sommario Le finalità del CENTRO STORICO CULTURALE 9 VALLE BREMBANA “FELICE RICEPUTI” (dall’atto costitutivo) Sostenitori, collaboratori e referenti 10 Presentazione 11 Attività dell’anno 2020 12 Il fotografo ritrovato 18 La Valle Brembana, e non solo, nelle fotografie di Andrea Milesi di Ornica (1867-1938), scattate tra il 1890 e il 1910 a cura del Direttivo Bortolo Belotti. -

Associazioni VALLE BREMBANA

INQUADRAME CONTATTI NTO TERRITORIO DI NOME ASSOCIAZIONE AREA TEMATICA GIURIDICO ATTIVITA' PREVALENTE RIFERIMENTO SEDE PRESIDENTE REFERENTE telefono e-mail sito Si occupa della promozione della donazione di Via Chiesa 3, fraz. sangue e dell'organizzazione di donazioni Algua-Bracca- Ascensione, 24010 0345/68019 A.V.I.S ALGUA-BRACCA-COSTA SERINA Sociale e Sanitaria Volontariato collettive. Costa Serina Costa Serina Cortinovis Mario Ghirardi Elio 347/3737910 [email protected] Protezione Civile e Tiene vive e tramanda le tradizioni degli alpini fraz. Frerola Micheli GRUPPO ALPINI FREROLA Ambientale Volontariato e il ricordo dei caduti di tutte le guerre. Algua 24010 Algua Micheli Giovanni Giovanni 0345 97163 [email protected] Ha cura del territorio e interviene in via don Tondini 16 occasione di calamità naturali; si occupa della Comunità c/o sede comunità SQUADRA LOCALE DI PROTEZIONE CIVILE Protezione Civile e sicurezza pubblica in occasione di importanti Montana Valle Montana Piazza Mazzoleni fioronaroberto@vallebrem E ANTINCENDIO BOSCHIVO Ambientale Volontariato manifestazioni. Brembana Brembana Alberto Fiorona Roberto 0345/81177 bana.bg.it Culturale/Ricreativa/ Coordina tutte le associazioni presenti nel Promozione del paese. Organizza feste, attività di promozione via Rigosa, 64 Marconi William 333/6043937 PRO LOCO RIGOSA Territorio Pro Loco culturale e del territorio. Algua 24010 Algua Marconi William Mattia Noris 332 3297486 [email protected] Si occupa della promozione culturale e Culturale/Ricreativa/ turistica del territorio, in stretta Promozione del collaborazione con il Comune e le fraz. Sambusita 0345/68019 ENTE LOCALE DEL TURISMO Territorio Pro Loco Associazioni presenti. Algua 24010 Algua Felappi Rino Ghirardi Elio 347/3737910 fraz. -

Documento-Di-Piano-Ptra-Valli-Alpine

PIANO TERRITORIALE REGIONALE D’AREA VALLI ALPINE OROBIE BERGAMASCHE E ALTOPIANO VALSASSINA Coordinatore: arch. G.A. Bravo (Ordine degli Architetti, P.P.C. - Prov. VA n°655) Progettista: arch. M. Federici (Ordine degli Architetti, P.P.C. - Prov. MI n°7074) Collaboratori principali: arch. W. Callini (Ordine degli Architetti, P.P.C. - Prov. VA n°1022) (Ordine degli Architetti, P.P.C. - Prov. MI n°3376) arch. P. Garbelli Ufficio di Piano: DG Territorio, Urbanistica e Difesa del Suolo Avviato dalla Giunta con DGR n. 4101 del 27.09.2012 Adottato dalla Giunta con DGR n. 2134 del 11.07.2014 Approvato dal Consiglio con DCR n. 654 del 10.03.2015 DOCUMENTO DI PIANO Aggiornamento 2019 ALLEGATO A ALLA DCR N. 654 DEL 10.03.2015 PTRA VALLI ALPINE COORDINAMENTO ISTITUZIONALE Viviana Beccalossi, Assessore al Territorio, Urbanistica e Difesa del suolo GRUPPO DI PROGETTO DI PIANO: Coordinatore del Progetto Arch. Gian Angelo Bravo (Iscritto all’Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori Prov. Varese n°655) Progettista Responsabile PTRA Arch. Maurizio Federici (Iscritto all’Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori Prov. Milano n°7074) Responsabile del Documento di Piano Arch. Walter Callini (Iscritto all’Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori Prov. Varese n°1022) Responsabile della Valutazione Ambientale Strategica Arch. Piero Garbelli (Iscritto all’Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori Prov. Milano n°3376) Collaboratori principali (DG Territorio, Urbanistica e Difesa del suolo) Fabio Cremascoli, Silvio de Andrea, Mauro Filì, Alberto Galazzetti, Alberto Giudici, Barbara Grosso, Matteo Ibatici, Antonio Lampugnani, Silvia Montagnana, Giovanni Morini, Chiara Penco, Antonella Pivotto, Rossella Radice, Sandra Zappella, Antonella Zucca. -

Skitouren Am Comer See Freudenschwünge Über Dem Lario

Skitouren am Comer See FREUDENSCHWÜNGE ÜBER DEM LARIO Der Comer See – oder „Lario“ – bietet Besuchern nicht nur malerische Dörfer und exzellente italienische Gastronomie in den Restaurants und Bars an seinem Ufer. Er ist von Bergen umrahmt, die zu Skitouren mit prächtigen Ausblicken einladen. Wenn genug Schnee liegt ... Text und Fotos von Christine Kopp ller Anfang ist schwer. Das gilt gebot an Literatur ist spärlich. Immerhin Dörfer und Berge oder wegen des einzig- auch, wenn man sich den Ski- ist rechtzeitig zur Saison ein neuer Skitou- artigen Gefühls, das sich durch die Ver- touren am Comer See annähert: ren-Führer erschienen (siehe Infokasten). bindung einer Skitour mit Cappuccino Nicht jeder Winter hier ist Wer die Hürden überwindet – auch dank und Brioche am Seeufer davor und italie- Aschneesicher, die Schneelage kann sich der stets hilfsbereiten Einheimischen –, nischer Kulinarik danach einstellt. Rich- schnell verändern und ist oft stark vom wird allerdings begeistert sein: etwa we- tig mediterran, und das hier, im Norden Nordwind beeinflusst, die Anfahrten sind gen der herrlichen Aussicht von einem der Lombardei. Und was den vielseitigen nicht ganz einfach zu finden, und das An- Gipfel wie dem Monte Bregagno auf See, Bergsportler freuen dürfte: Hier kann 84 DAV 1/2014 Comer See REPORTAGE FREUDENSCHWÜNGE ÜBER DEM LARIO man in guten Wintern durchaus einen kenwald hinter sich, geht es in offenem gang aufsteigen: Der Blick schweift von Skitouren-Urlaub mit einem Tag Klettern Gelände entlang des Dosso di Naro hoch. dem Rücken über die Schneekuppen, die im ärmellosen Shirt verbinden, etwa am Man möchte am liebsten im Rückwärts- hier oft vom Nordwind gewellt sind, hin- sonnenverwöhnten Sasso di Pelo in der unter zum See mit seinen eng verschach- Gemeinde von Gravedona oder an der telten Dörfern. -

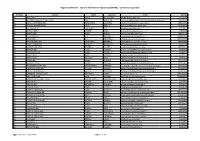

Sitab) - Comuni Con Operatori

Regione Lombardia - Sistema Informativo Taglio Bosco (SITaB) - Comuni con operatori Provincia Comune Nome Cognome Email Telefono BG ALGUA (BG) PAOLA DEL VECCHIO [email protected] 034597009 BG ALMENNO SAN BARTOLOMEO (BG) LORIS MAGGIONI [email protected] 0364434490 BG ALZANO LOMBARDO (BG) ALESSANDRO COLOMBO [email protected] 0354492961 BG ALZANO LOMBARDO (BG) IVAN NOVELLI [email protected] 0354389730 BG AVERARA (BG) LOREDANA BUSI [email protected] 034580313 BG AVIATICO (BG) WALTER MILESI [email protected] 035763250 BG AZZONE (BG) GIADA BETTONI [email protected] 0346/51133 BG BERBENNO (BG) IVO MANZINALI [email protected] 03488134268 BG BLELLO (BG) IVO MANZINALI [email protected] 03491593591 BG BONATE SOPRA (BG) MGIOVANNA BREMBILLA [email protected] 0364434043 BG BONATE SOPRA (BG) PATRIZIA MEDOLAGO [email protected] 0364434490 BG BONATE SOTTO (BG) VENANZIO LOCATELLI [email protected] 0364434012 BG BOSSICO (BG) lorenzo savoldelli [email protected] 035968020 BG BOTTANUCO (BG) MORIS PAGANELLI1 [email protected] 035906631 BG BRACCA (BG) ALAN CHIAPPA [email protected] 034597123 BG BRACCA (BG) Giuseppe Giassi [email protected] 034597123 BG BRANZI (BG) Saverio De Vuono [email protected] 0345/71006 BG BREMBATE (BG) Claudia Del Prato [email protected] 0362396354 BG -

L'italie Et Ses Dialectes

L’Italie et ses dialectes Franck Floricic, Lucia Molinu To cite this version: Franck Floricic, Lucia Molinu. L’Italie et ses dialectes. Lalies (Paris), Paris: Presses de l’Ecole normale supérieure, 2008, 28, pp.5-107. halshs-00756839 HAL Id: halshs-00756839 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00756839 Submitted on 26 Nov 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LALIES 28 L’ITALIE ET SES DIALECTES1 FRANCK FLORICIC ET LUCIA MOLINU 0. INTRODUCTION GÉNÉRALE En dépit du fait que les langues romanes soient particulièrement bien étudiées et, généralement, bien connues dans leurs structures fondamentales, le domaine linguistique italien reste pour une grande part à défricher. Rohlfs observait que peu de domaines linguistiques offrent une fragmentation et une hétérogénéité analogues à celles que présente le domaine italo-roman. Inutile de dire dans ces conditions qu’il est impossible de rendre compte – même en ayant à sa disposition plus d’espace qu’à l’accoutumée – d’une telle diversité et d’une telle variété ; il va sans dire aussi qu’un article de synthèse ne peut que décevoir le lecteur désireux d’y trouver une description exhaustive des caractéristiques de tel ou tel dialecte. -

Prot 15545 Del 10.12.2020 Ato Bergamo Osservazioni

" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " FOPPOLOFOPPOLO " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " MEZZOLDO " MEZZOLDO " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " CARONACARONA " " " " VALLEVEVALLEVE VALBONDIONEVALBONDIONE " " " " SCHILPARIOSCHILPARIO " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " O " " " " B " " M " " " " " AVERARA " " AVERARA " " E " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " R " " " GANDELLINO " " " GANDELLINO " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " B VILMINORE " " VILMINORE " " D I S C A L V E " ORNICA " " O SANTASANTA " " E " " PIAZZATORRE " BRIGIDABRIGIDA PIAZZATORRE " " " B " CUSIOCUSIO " M " " BRANZIBRANZI " " " M " " U " " " " " " E I " " VALTORTAVALTORTA VALGOGLIOVALGOGLIO " " " R F " " " AZZONEAZZONE " " B II S S O O L L A A DD I I " " " " FONDRAFONDRA " GROMO " PIAZZOLO GROMO " " " PIAZZOLO " " " " " " " E " " " " " " " " " " " " " " COLERECOLERE " " " " M O I O D E ` " " M " " CALVI CALVI " " O L M O A L " " BREMBO " BREMBO " " U " " VALNEGRAVALNEGRA " " CASSIGLIOCASSIGLIO I " " " OLTRESSENDA PIAZZAPIAZZA OLTRESSENDA " F RONCOBELLORONCOBELLO " ALTA " BREMBANABREMBANA ALTA