RRC Body Refs Changed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brochure FINAL 1A.Docx

Name(s) Mr, Mrs. Ms. other RAILWAY & CANAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY .......................................................................... Address 1: ................................................................ The Railway & Canal Historical Society was founded in 1954. Its objective is to bring together all ..................................................Post Code..................... Industrial Heritage Day those seriously interested in the history of transport, Address 2: ................................................................. with particular reference to railways and waterways, EMIAC 96 ..................................................Post Code..................... although the Society also caters for those interested Saturday 11th May 2019 Email: .......................................................................... in roads, docks, coastal shipping and air transport To be held at the The Summit Centre Pavilion Road, Kirkby in Ashfield, NG17 7LL. Telephone: ................................................................... The East Midlands Group normally meets on the Society (if any): first Friday evening of each month from October to Mansfield & Pinxton Railway .......................................................................... April in Beeston. During the summer months tours (1819) and visits are made to places of historical interest Would you like to be informed about future EMIAC events and importance in the transport field. Full details of Introduction by e-mail.? YES/NO. the R & C H S can be obtained -

BE PREPARED for Major Disruptions at Nottingham Station 20 July – 25 August

BE PREPARED FOR MAJOR DISRUPTIONS AT NOTTINGHAM STATION 20 July – 25 AuguST Avoid the worry by registering for updates at eastmidlandstrains.co.uk/nottingham we’ll be helping yOU TO STAY ON THE MOVE MAJOR RESIGNALLING WORKS 20 July – 25 AuguST This summer, Nottingham station will be affected by the Nottingham resignalling project, which will cause major disruptions to train services between 20 July and 25 August. In this leaflet you’ll find information about the works and how service changes will affect you, so that you can be prepared and plan your journeys without worry. WHAT IS THE NOTTINGHAM RESIGNALLING PROJECT? It is a project by Network Rail to improve Nottingham station and transform the railways around the city. Big changes to tracks and signalling will mean more reliable services and fewer delays at Nottingham station, and the railways will be able to cope with an increasing demand for rail travel in the future. WHAT WILL THE PROJECT INVOLVE? • £100 million investment • A new platform at Nottingham station • 143 new signals • Six miles of new track • Three new signal boxes • Two renewed level crossings • Two level crossings replaced with footbridges. SIGN UP NOW Register online today for the latest updates at eastmidlandstrains.co.uk/nottingham 2 AT A GLANCE Below is a summary of the changes to the train services for each of the affected routes. Details and a map for each route can be found further on within this leaflet. NOTTINGHAM – LONDON (p.5) Train services to/from london will start and terminate at East Midlands Parkway, with three services per hour running between East Midlands Parkway and london. -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

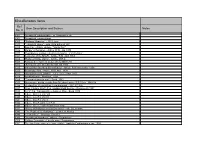

Miscellaneous Items Ref Item Description and Source Notes No

Miscellaneous Items Ref Item Description and Source Notes No. X X003 Scrapbook, photographs - ex. Magazines etc. X004 Scrapbook, newscuttings X007 "Railway Magazine" - 1912 June X012 "Travels at Home" - pub. With authy of G.C X015 Sam Fay - Article, picture, "Vanity Fair" X016 Murder in Pennines - Article, R.W. Jan 1970 X017 Past Glories, station refreshment rooms - V.R.Webster X021 A veteran of the MSLR - Article, R.M. April 1959 X022 Wadsley bridge station - Article, M.R.C X023 Railway development at Aylesbury BM No 55 X024 Diversions over Woodhead RM Jan 1970 X025 Manchester-Sheffield Electrification - Article, R.M. November 1954 X026 Bowbridge Pilot - Article, R.M. Nov. 1954 X027 Abandonment of SAMR? - letter, Dec. 22nd. 1837 X028 Accident book - Mexboro', 1925 X029 "Transport goes to war" - Book, 1942 X033 Occurrence books, mainly from Mexboro' area - B.R 16 no. 1948-58 X036 Prospectus, Preservation Loughborough - G.C.R 1976 X037 Prop. Closure Sheff.-Pen.-Huddersfield Service - Documents 1981 X038 S.Y.P.T.E. Transport Development Plan - Book 1978 X039 Index - G.C.R.J Vol. VIII X040 Index - G.C.R.J Vol. IX X041 Index - G.C.R.J Vol. X X042 Index - G.C.R articles in R.M X043 Index - G.C.R. LDECR articles in R.M X044 History of Railways around Doncaster - Ms, D.L.Franks X045 "The Plight of the Railways" - Leaflet, G.Huxley X046 "I remember" - Glossop - Booklet X049 "Woodhead Wanderer" railtour - Programme X050 Railtour Doncaster - Lincoln area - Programme X051 The Iron horse comes to town - Article, Appleby-Frodingham news, 1959 X054 The Yarborough Hotel - Notes, from Bradshaw 1853 X055 When service had meaning, The Story of and Early Railwayman's life - D.L Franks X056 Seven ages of Rlys - Ms, D.L. -

Golfer's Guide for the United Kingdom

Gold Medals Awarded at International Exhibitions. AS USED BY HUNDREDS THE OF CHAMPION UNSOLICITED PLAYERS. TESTIMONIALS. Every Ball Guaranteed in Properly Matured Condition. Price Ms. per dozen. The Farthest Driving- and Surest Putting- Ball in the Market. THORNTON GOLF CLUBS. All Clubs made from Best Materials, Highly Finished. CLUB COVERS AND CASES. Specialities in aboue possessing distinct improuements in utility and durability. Every Article used in Golf in Perfection of Quality and Moderation in Price. PKICE LIST ON APPLICATION. THORNTON & CO., Golf Appliance Manufacturers, 78 PRINCES STREET, EDINBURGH. BRANCHES—, LEEDS, BRADFORD, aqd BELFAST. ' SPECI A L.1TIE S. WEDDING PRESEF ELECTRO-SILVER PLATE JAMES GRAY & SON'S NEW STOCK of SILVER-PLATED TEA and COFFEE SETS, AFTER- NOON TEA SETS, CASES "I FRUIT and FISH KNIVES and FORKS, in Pearl or Ivory Handles, FINE CASES OF MEAT AND FISH CARVERS, TEA and FELLY SPOONS In CASES. CASES of SALTS, CREAM, and SUGAR STANDS. ENTREE DISHES, TABLE CUTLERY, and many very Attractive and Useful Novelties, suitable for Marriage and other Present*. NEW OIL LAMPS. JAMES GRAY & SON Special De*lgn« made for their Exclusive Sale, In FINEST HUNGARIAN CHINA, ARTISTIC TABLE and FLOOR EXTENSION [.AMI'S In Brass, Copper,and Wrougnt-Iroti, Also a very Large Selection of LAMP SHADES, NBWMT DJUUQWB, vary moderate In price. The Largest and most Clioieo Solootion in Scotland, and unequallod in value. TnspecHon Invited. TAb&ral Heady Money Dlgcount. KITCHEN RANGES. JAMES GRAY & SON Would draw attention to their IMPROVED CONVERTIBLE CLOSE or OPEN FIRE RANGE, which is a Speciality, constructed on Liu :best principles FOR HEATINQ AND ECONOMY IN FUEL. -

The London Gazette, 27 March, 1923

2344. THE LONDON GAZETTE, 27 MARCH, 1923. (Derbyshire Lines), bridge carrying the Scottish Railway (Blackwell Branch) over road from Tibshelf to Sawpit Lane over Fordbridge Lane. -the London and North Eastern Railway Parish of Tibshelf— (Tibshelf Colliery Branch). Bridges carrying the London, Midland (D) Roads under the following bridges:— and Scottish Railway over the roads from Tibshelf to Westhouses and from Tibshelf In the urban district of Sutton-in-Ash- to Morton, bridge carrying the London, fieldt— Midland and Scottish Railway (Tibshelf Bridge carrying the London and North and Pleasley) over Newton Lane, bridges Eastern Railway (Mansfield Railway) over carrying the London and North Eastern Coxmoor Road. Railway (Derbyshire Lines) over Newton Lane and Pit Lane, bridge carrying the In the urban district of Kirkby-in-Ash- London and North Eastern Railway (Tib- field:— shelf Colliery Branch) over Sawpit Lane. Bridge carrying the London, Midland and (E) Railways: — Scottish Railway (Mansfield and Pinxton) over Mill Lane, bridge carrying the In the urban district of Sutton-in-Ash- •London, Midland and Scottish Railway field: — (Bentinck Branch) over Park Lane, bridge Level crossings of the London, Midland carrying the London and North Eastern and Scottish Railway (Nottingham and Railway (Langton Colliery Branch) over Mansfield) in Station Road and Coxmoor the road from Kirkby-in-Ashfield to Road. - Finxton, bridges carrying^ mineral rail- ways at Kirkby Colliery over Southwell In the urban district of Huthwaiter — Lane, bridge carrying mineral railway at Level crossing of mineral railway from Bentinck Colliery over Mill Lane. New Hucknall Colliery in Common Road. In the urban district of Kirkby-in-Ash- In the rural district of Basford: — field: — Parish of Linby— Bridge carrying the London and NortL .Level crossings of the London, Midland Eastern Railway over the road from and Scottish Railway (Nottingham and Linby to Annesley. -

Kings Clipstone History Guide

Kings Clipstone The royal heart of ancient Sherwood Forest The guide to the royal heart of ancient Sherwood £2.00 www.HeartOfAncientSherwood.co.uk The Village The village layout in 2005. The layout of Kings Clipstone has probably altered little in 1000 years. The 1630 map of the village shows it to be remarkably similar to the present day village with the houses strung out along the road between the Castle Field and the Great Pond with most of the dwellings to the north of the road with plots down to the river. It would never have been easy to make a living from the poor sandy soil. The villagers of 1630 would have had important rights to use the forest but the middle years of the 17 th century saw most of the forest around the village destroyed to produce charcoal for the iron forges. The second half of the 18th century saw the enclosure of 2000 acres of open land. The 1832 directory described the village as being in a sad state, one of the worst in Bassetlaw. As part of his irrigation scheme, the Duke of Portland demolished most of the houses on the side of the village nearest the Maun and replaced them with a model village. The semi-detached houses had a large paddock each, so that the residents, who worked on the estate, could be more self-sufficient. By 1842 the description of the village had changed to ‘ being in danger of becoming one of the neatest’. The 1630 & 1754 maps transposed onto a modern map. -

Designating Local Green Space Technical Paper, 2015

Mansfield District Council Local Plan Consultation Draft Designating Local Green Space Technical Paper December 2015 www.mansfield.gov.uk Designating Local Green Space in Mansfield District 1 What is local green space? 2 1.1 A new way of protecting green spaces 2 1.2 Local green space designation criteria 3 Contents 2 The district at a glance 7 2.1 Places and connections 7 2.2 Considering protected green space 7 3 Identifying local green spaces in Mansfield district 8 3.1 Public consultation 8 3.2 Reviewing the submissions 9 3.3 Assessing nominated sites - applying the criteria 10 4 Draft local green space sites 14 5 Protecting and enhancing green spaces, connections and the countryside 18 6 Next steps 19 6.1 Consultation of the local plan 19 6.2 Local green space policy 19 6.3 Local plan adoption - formalising the local green space designations and policy 19 Appendices Appendix A Public consultation website information 20 Appendix B Local green space public nomination form 23 Appendix C Officer site visit assessment sheet 26 Appendix D Individual site maps and selection criteria for nominated sites 28 Appendix E Public consultation exercise 70 1 What is local green space? 1.1 This paper is an evidence base for the Local Plan (up to 2033) concerning designated areas of Local Green Space. The following sections set out site were identified for protection and inclusion on the Mansfield District Local Plan proposal's map. 1.1 A new way of protecting green spaces 1.2 In March 2012, the Government made it possible for green spaces with a special community importance to qualify for a new protection status. -

Stapleford to Nuthall

High Speed Two Phase 2b ww.hs2.org.uk October 2018 Working Draft Environmental Statement High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report | Volume 2 | LA06 LA06: Stapleford to Nuthall High Speed Two (HS2) Limited Two Snowhill, Snow Hill Queensway, Birmingham B4 6GA Freephone: 08081 434 434 Minicom: 08081 456 472 Email: [email protected] H17 hs2.org.uk October 2018 High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report LA06: Stapleford to Nuthall H17 hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Two Snowhill Snow Hill Queensway Birmingham B4 6GA Telephone: 08081 434 434 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. © High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2018, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. -

George E. Tillitson Collection on Railroads M0165

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1j49n53k No online items Guide to the George E. Tillitson Collection on Railroads M0165 Department of Special Collections and University Archives 1999 ; revised 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the George E. Tillitson M0165 1 Collection on Railroads M0165 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: George E. Tillitson collection on railroads creator: Tillitson, George E. Identifier/Call Number: M0165 Physical Description: 50.5 Linear Feet(9 cartons and 99 manuscript storage boxes) Date (inclusive): 1880-1959 Abstract: Notes on the history of railroads in the United States and Canada. Conditions Governing Access The collection is open for research. Note that material is stored off-site and must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. Provenance Gift of George E. Tillitson, 1955. Special Notes One very useful feature of the material is further described in the two attached pages. This is the carefully annotated study of a good many of the important large railroads of the United States complete within their own files, these to be found within the official state of incorporation. Here will be included page references to the frequently huge number of small short-line roads that usually wound up by being “taken in” to the larger and expending Class II and I roads. Some of these files, such as the New York Central or the Pennsylvania Railroad are very big themselves. Michigan, Wisconsin, Oregon, and Washington are large because the many lumber railroads have been extensively studied out. -

O Winston Link 1957 25.00 102 Realistic Track

To contact us, please either phone us on 07592-165263 or 07778-184954 or email us at [email protected] List created June 28th 2021 “Night Trick” on the Norfolk and Western card cover, 16 pages, edges Railway (USA) O Winston Link 1957 rubbed, otherwise good 25.00 102 realistic track plans (USA) 2008 Kalmbach light card cover, good 2.00 150 years of the Lancashire & Yorkshire Hawkshill Railway Noel Coates Publishing 1900349116 card cover, new 10.00 16mm Scale Live Steam Model Nelson & card cover, cup mark to rear, Locomotives Vol 1 16mm narrow gauge Peter Dobson 1985 Saunders Ltd 0947750010 otherwise good 12.00 1948 British Railways Locomotives Orig 1948 combined volume, complete list of all reprint hardback, dust jacket marked, no engines in service in 1948 1966 Ian Allan underlines, otherwise good 8.00 Karl R 20th Century Limited (USA) Zimmermann 2002 MBI Publishing 0760314225 hardback, dust jacket & book good 30.00 Steve le Cheminant, Vernon Murphy, Tele Rail 21st Century Extreme Steam (China) Michael Rhodes 2003 Publications 0953789012 hardback, dust jacket & book good 4.00 25 Years of Railway Research Colin J Marsden 1989 OPC 0860934411 hardback, dust jacket & book good 5.00 3000 Strangers, navvy life on the Kettering to Manton railway J Ann Paul 2003 Silver Link 1857942124 card cover, good 4.00 4ft 8½ and all that, a sort of railway hardback, dust jacket edges history W Mills 1964 Ian Allan rubbed, otherwise good 2.00 4ft 8½ and all that, a sort of railway history W Mills 2007 Ian Allan 0711009611 hardback, dust jacket & book -

Green Network News

‘Iv ‘@165 .» F R E E A BREATH OF FRESH AIR No.41 June 1995 2 gggggétitkti tiéillié Inside... Nottingham Women’s Environmental Network The National WEN campaign ‘Ease the Wheeze ’ ...‘..._..._..‘.'._._. _ . ‘ . _ . I . I . I. ...--.-...-.|-...<. (NWEN) is increasingly concerned about the aims to - h . ._._._._. ._._1_._. - Transport Focus effects of air pollution on our quality of life and ~ promote affordable and reliable - Green Videos health, and is focusing its effortsthis summer on alternatives to the car A - Composting Offer - promote traffic-free routes within the a ‘Breath of Fresh Air’ Campaign. /' community -_ "‘ -\ K 1/» Vehicles are now the greatest air polluters in the - encourage women’sinvolvementinlocal ' "', \ ,___.,~ r GLOBAL FUTURE UK. Recent research has clearly demonstrated planning and decision making processes P ’ I -\...F-_.__. links between the alarming increase in respiratory / /s“ _-J“? illnesses such as asthma (especially in children) WEN will be informing people about the effects /T.» ‘§. \’_ .--"""_ The ‘Our Global Future’ festival for the and the ever increasing amount of air pollution of air pollution and how they can reduce their I ’ _. __, \\\__- environment took place from 18-21 May at caused by vehicle emissions. exposure to pollutants, reduce their impact on is __.--‘"5’ I‘ /; 5 the Harvey Hadden Sports Centre in the environment, and campaign for change. J __ Bilborough. More than 150 exhibitors =§ -;. \ Despite this evidence, there is still no real ' )\ -"1 provided over 10,000 square metres of commitment from the govemment to reduce the Nottingham WEN’ s own demonstration will take entertainment and information.