Kings Clipstone History Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nottinghamshire's Sustainable Community Strategy

Nottinghamshire’s Sustainable Community Strategy the nottinghamshire partnership all together better 2010-2020 Contents 1 Foreword 5 2 Introduction 7 3 Nottinghamshire - our vision for 2020 9 4 How we put this strategy together What is this document based on? 11 How this document links with other important documents 11 Our evidence base 12 5 Nottinghamshire - the timeline 13 6 Nottinghamshire today 15 7 Key background issues 17 8 Nottinghamshire’s economy - recession and recovery 19 9 Key strategic challenges 21 10 Our priorities for the future A greener Nottinghamshire 23 A place where Nottinghamshire’s children achieve their full potential 27 A safer Nottinghamshire 33 Health and well-being for all 37 A more prosperous Nottinghamshire 43 Making Nottinghamshire’s communities stronger 47 11 Borough/District community strategies 51 12 Next steps and contacts 57 Nottinghamshire’s Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-2020 l p.3 Appendices I The Nottinghamshire Partnership 59 II Underpinning principles 61 III Our evidence base 63 IV Consultation 65 V Nottinghamshire - the timeline 67 VI Borough/District chapters Ashfield 69 Bassetlaw 74 Broxtowe 79 Gedling 83 Mansfield 87 Newark and Sherwood 92 Rushcliffe 94 VII Case studies 99 VIII Other relevant strategies and action plans 105 IX Performance management - how will we know that we have achieved our targets? 107 X List of acronyms 109 XI Glossary of terms 111 XII Equality impact assessment 117 p.4 l Nottinghamshire’s Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-2020 1 l Foreword This document, the second community strategy for Nottinghamshire, outlines the key priorities for the county over the next ten years. -

Brochure FINAL 1A.Docx

Name(s) Mr, Mrs. Ms. other RAILWAY & CANAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY .......................................................................... Address 1: ................................................................ The Railway & Canal Historical Society was founded in 1954. Its objective is to bring together all ..................................................Post Code..................... Industrial Heritage Day those seriously interested in the history of transport, Address 2: ................................................................. with particular reference to railways and waterways, EMIAC 96 ..................................................Post Code..................... although the Society also caters for those interested Saturday 11th May 2019 Email: .......................................................................... in roads, docks, coastal shipping and air transport To be held at the The Summit Centre Pavilion Road, Kirkby in Ashfield, NG17 7LL. Telephone: ................................................................... The East Midlands Group normally meets on the Society (if any): first Friday evening of each month from October to Mansfield & Pinxton Railway .......................................................................... April in Beeston. During the summer months tours (1819) and visits are made to places of historical interest Would you like to be informed about future EMIAC events and importance in the transport field. Full details of Introduction by e-mail.? YES/NO. the R & C H S can be obtained -

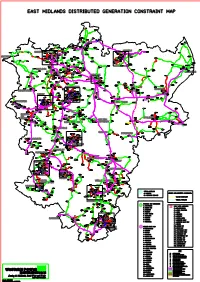

East Midlands Constraint Map-Default

EAST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP MISSON MISTERTON DANESHILL GENERATION NORTH WHEATLEY RETFOR ROAD SOLAR WEST GEN LOW FARM AD E BURTON MOAT HV FARM SOLAR DB TRUSTHORPE FARM TILN SOLAR GENERATION BAMBERS HALLCROFT FARM WIND RD GEN HVB HALFWAY RETFORD WORKSOP 1 HOLME CARR WEST WALKERS 33/11KV 33/11KV 29 ORDSALL RD WOOD SOLAR WESTHORPE FARM WEST END WORKSOPHVA FARM SOLAR KILTON RD CHECKERHOUSE GEN ECKINGTON LITTLE WOODBECK DB MORTON WRAGBY F16 F17 MANTON SOLAR FARM THE BRECK LINCOLN SOLAR FARM HATTON GAS CLOWNE CRAGGS SOUTH COMPRESSOR STAVELEY LANE CARLTON BUXTON EYAM CHESTERFIELD ALFORD WORKS WHITWELL NORTH SHEEPBRIDGE LEVERTON GREETWELL STAVELEY BATTERY SW STN 26ERIN STORAGE FISKERTON SOLAR ROAD BEVERCOTES ANDERSON FARM OXCROFT LANE 33KV CY SOLAR 23 LINCOLN SHEFFIELD ARKWRIGHT FARM 2 ROAD SOLAR CHAPEL ST ROBIN HOOD HX LINCOLN LEONARDS F20 WELBECK AX MAIN FISKERTON BUXTON SOLAR FARM RUSTON & LINCOLN LINCOLN BOLSOVER HORNSBY LOCAL MAIN NO4 QUEENS PARK 24 MOOR QUARY THORESBY TUXFORD 33/6.6KV LINCOLN BOLSOVER NO2 HORNCASTLE SOLAR WELBECK SOLAR FARM S/STN GOITSIDE ROBERT HYDE LODGE COLLERY BEEVOR SOLAR GEN STREET LINCOLN FARM MAIN NO1 SOLAR BUDBY DODDINGTON FLAGG CHESTERFIELD WALTON PARK WARSOP ROOKERY HINDLOW BAKEWELL COBB FARM LANE LINCOLN F15 SOLAR FARM EFW WINGERWORTH PAVING GRASSMOOR THORESBY ACREAGE WAY INGOLDMELLS SHIREBROOK LANE PC OLLERTON NORTH HYKEHAM BRANSTON SOUTH CS 16 SOLAR FARM SPILSBY MIDDLEMARSH WADDINGTON LITTLEWOOD SWINDERBY 33/11 KV BIWATER FARM PV CT CROFT END CLIPSTONE CARLTON ON SOLAR FARM TRENT WARTH -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire Further electoral review December 2005 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 15 2 Current electoral arrangements 19 3 Submissions received 23 4 Analysis and draft recommendations 25 Electorate figures 26 Council size 26 Electoral equality 27 General analysis 28 Warding arrangements 28 a Clipstone, Edwinstowe and Ollerton wards 29 b Bilsthorpe, Blidworth, Farnsfield and Rainworth wards 30 c Boughton, Caunton and Sutton-on-Trent wards 32 d Collingham & Meering, Muskham and Winthorpe wards 32 e Newark-on-Trent (five wards) 33 f Southwell town (three wards) 35 g Balderton North, Balderton West and Farndon wards 36 h Lowdham and Trent wards 38 Conclusions 39 Parish electoral arrangements 39 5 What happens next? 43 6 Mapping 45 Appendices A Glossary and abbreviations 47 B Code of practice on written consultation 51 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

Broomhill Lodge, Off Mansfield Road, Edwinstowe, Notts, NG21 9HG for Sale: £695 Per Calendar Month Or to Let: £695 Per Calendar Month

CHARTERED SURVEYORS AUCTIONEERS VALUERS ESTATE AGENTS barnes EST. 1932 Broomhill Lodge, Off Mansfield Road, Edwinstowe, Notts, NG21 9HG For Sale: £695 Per calendar month or To Let: £695 Per calendar month We are delighted to offer for let this lovely character detached property which is well presented throughout with three bedrooms. Located within a rural position with fabulous views over open farmland. The property stands on a good sized plot with mature gardens and in brief comprises of entrance porch, entrance hall, spacious living room with open coal fire, separate dining room and modern breakfast kitchen (built in oven/hob) with utility room off. To the first floor are three good sized bedrooms plus family bathroom having 3 piece suite and shower over the bath. There is a detached garage and driveway. We would recommend an early viewing so not to be disappointed as these type of properties rarely come onto the market for let. Excellent employers references essential. Please NO PETS. EPC Rating E copy of which is available upon request. Ready for immediate let. Bond £795 VIEWING ACCOMPANIED NOTE:- W A BARNES LLP FEES PAYABLE AS FOLLOWS:- £20 inclusive of VAT (non-refundable) per applicant over the age of 18 years to undertake a credit check. An additional fee of £150 inclusive of VAT per property will be charged when signing the 6 month Assured Shorthold Tenancy Agreement •Lovely Character home • Three good sized bedrooms • Ready for immediate let •Views over open farmland • First floor bathroom/w.c • Please No pets as working •Modern kitchen -oven & hob • Good sized gardens with farm •Two reception rooms • garage and driveway • EPC Rating E • Bond £795 W A BARNES LLP PORTLAND SQUARE SUTTON IN ASHFIELD NOTTINGHAMSHIRE NG17 1DA tel 01623 554084 / 553929 fax 01623 550764 email [email protected] web www.wabarnes.co.uk barnes EST. -

Licensing Committee 3 September 2020

LICENSING COMMITTEE 3 SEPTEMBER 2020 UPDATE ON PERFORMANCE AND ENFORCEMENT MATTERS 1.0 Purpose of Report 1.1 To inform Committee of the activity and performance of the licensing team between 1 January and 30 June 2020 inclusive and to provide Members with details of current going enforcement issues. 2.0 Background 2.1 This report covers the period from 1 January and 30th June 2020 inclusive and sets out the range and number of licence applications during this period. It also highlights any activity required as a result of the applications. Activity Report for 1 January to 30 June 2020 Number Number Number Application Type Comments Received Issued Refused Personal Licence 15 15 Vary the Designated Premise 26 26 Supervisor Transfer of Premise Licence 12 12 Minor Variation 3 3 Variation to Premise Licence 5 5 New Premise licence 7 6 1 pending Change of Premise Name 0 0 Notification of Interest 1 1 Temporary Event Notices 53 53 2.2 By way of comparison, the number of Temporary Event Notices received for the same period last year was 192. 2.3 Enforcement Activity Ongoing Enforcement Activity 1 January and 30 June 2020 Location Summary Of Action Taken So Far Date Case Complaint/Reason Opened For Visit Black Swan Noise complaint 2.1.2020 LEO visited premise and advice given High Street to DPS. Edwinstowe Further noise complaints 2/2/2020 – NG21 9QR DPS issued with written warning The Old Post Office Premise licence 13.1.2020 All in order Kirk Gate check Newark On Trent NG24 1AB The Rutland Arms Premise licence 13.1.2020 All in order 13 Barnby Gate check Newark On Trent NG24 1PX The White Hart Premise licence 13.1.2020 All in order 5 White Hart Yard check Newark On Trent NG24 1DX The Mayze Premise licence 13.1.2020 All in order 7 Castle Gate check Newark On Trent NG24 1AZ Haywood Oaks Golf Premise licence 14.1.2020 2 action points to be followed up. -

Southwell and Nottingham

Locality Church Name Parish County Diocese Date Grant reason ALLENTON Mission Church ALVASTON Derbyshire Southwell 1925 New Church ASKHAM St. Nicholas ASKHAM Nottinghamshire Southwell 1906-1908 Enlargement ATTENBOROUGH St. Mary Magdalene ATTENBOROUGH Nottinghamshire Southwell 1948-1950 Repairs ATTENBOROUGH St. Mary Magdalene ATTENBOROUGH Nottinghamshire Southwell 1956-1957 Repairs BALDERTON St. Giles BALDERTON Nottinghamshire Southwell 1930-1931 Reseating/Repairs BAWTRY St. Nicholas BAWTRY Yorkshire Southwell 1900-1901 Reseating/Repairs BLIDWORTH St. Mary & St. Laurence BLIDWORTH Nottinghamshire Southwell 1911-1914 Reseating BLYTH St. Mary & St. Martin BLYTH Derbyshire Southwell 1930-1931 Repairs BOLSOVER St. Mary & St. Laurence BOLSOVER Derbyshire Southwell 1897-1898 Rebuild BOTHAMSALL St. Peter BOTHAMSALL Nottinghamshire Southwell 1929-1930 Repairs BREADSALL All Saints BREADSALL Derbyshire Southwell 1914-1916 Enlargement BRIDGFORD, EAST St. Peter BRIDGFORD, EAST Nottinghamshire Southwell 1901-1905 Repairs BRIDGFORD, EAST St. Peter BRIDGFORD, EAST Nottinghamshire Southwell 1913-1916 Repairs BRIDGFORD, EAST St. Peter BRIDGFORD, EAST Nottinghamshire Southwell 1964-1969 Repairs BUXTON St. Mary BUXTON Derbyshire Southwell 1914 New Church CHELLASTON St. Peter CHELLASTON Derbyshire Southwell 1926-1927 Repairs CHESTERFIELD Christ Church CHESTERFIELD, Holy Trinity Derbyshire Southwell 1912-1913 Enlargement CHESTERFIELD St. Augustine & St. Augustine CHESTERFIELD, St. Mary & All Saints Derbyshire Southwell 1915-1931 New Church CHILWELL Christ Church CHILWELL Nottinghamshire Southwell 1955-1957 Enlargement CLIPSTONE All Saints, New Clipstone EDWINSTOWE Nottinghamshire Southwell 1926-1928 New Church CRESSWELL St. Mary Magdalene CRESSWELL Derbyshire Southwell 1913-1914 Enlargement DARLEY St. Mary the Virgin, South Darley DARLEY, St. Mary the Virgin, South Darley Derbyshire Southwell 1884-1887 Enlargement DERBY St. Dunstan by the Forge DERBY, St. James the Great Derbyshire Southwell 1889 New Church DERBY St. -

JULY 2019 Plan Review - Allocations & Development Management Issues Paper

PLAN REVIEW REVIEW OF THE NEWARK & SHERWOOD LOCAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK CORE STRATEGY & ALLOCATIONS ALLOCATIONS & DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT ISSUES PAPER JULY 2019 Plan Review - Allocations & Development Management Issues Paper 1.0 Introduction 1.1 The District Council has been reviewing the various elements of Newark & Sherwood’s Development Plan over the past four years. The plan is now made up of the Amended Core Strategy (Adopted 7th March 2019), the Allocations & Development Management DPD (Adopted 2013) and ‘made’ Neighbourhood Plans’ (currently including those for Farnsfield, Fernwood, Kings Clipstone, Southwell and Thurgarton). 1.2 Following the Adoption of the Amended Core Strategy DPD earlier this year, the remaining elements of the Plan Review, which are made up of the allocations and development management policies contained within the Allocations and Development Management DPD will now need to be progressed; along with a new strategy and allocations to meet future housing need for Gypsy & Travellers in the District. It should be noted that as part of updating the general housing and employment section of the DPD we are not intending to identify any other new allocations (see section 8). 1.3 It should also be noted that in July 2018 the Government published an updated National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), which was subject to further clarifications and re-issued in February 2019. It is therefore necessary to ensure that all elements of the Development Plan continue to be in compliance with national policy. 1.4 The remainder of this paper provides a position statement on the Plan Review: Section 2 considers the new NPPF and the various issues of conformity with regard to the Adopted Amended Core Strategy and the Development Management Policies that are still being considered as part of the Plan Review. -

King John's Palace

Kings Clipstone A royal residence for the Plantagenet Kings King John’s Palace or the The King’s Houses cost £2.00 www.HeartOfAncientSherwood.co.uk The ruins known as King John’s Palace are only a small part of this important royal residence. The part of the site that has been investigated has yielded a wealth of information that confirms there was a complex of high status buildings on this site. Royal records show that this was the favoured residence for the Plantagenet Kings when in the area. It was only during the 20th century that the ruins became known as a hunting lodge. The visible ruins adult standing on the site The ruined walls you can see are only a very small part of the site. The early History of the site The earliest archaeological remains on the site date from 2 nd century AD. The proximity to the river Maun and the Ramper brook make this one of the few sites suitable for settlement within the ancient forest of Sherwood. Field walking has yielded shards of Roman pottery. Also the excavation by Rahtz in 1956 and the geophysics survey in 2004 both identify the line of a typical J shaped Roman defensive ditch, probably excavated to protect a Roman villa. The Domesday survey of 1185 shows a Saxon Manor in the village held before the conquest by Osbern and Ulsi. The Manor of Clipstone was granted by William the Conqueror to Roger de Busli, just one of 107 he held. The amount of land reclaimed from the forest and under cultivation was considerably more than in surrounding villages. -

Miscellaneous Items Ref Item Description and Source Notes No

Miscellaneous Items Ref Item Description and Source Notes No. X X003 Scrapbook, photographs - ex. Magazines etc. X004 Scrapbook, newscuttings X007 "Railway Magazine" - 1912 June X012 "Travels at Home" - pub. With authy of G.C X015 Sam Fay - Article, picture, "Vanity Fair" X016 Murder in Pennines - Article, R.W. Jan 1970 X017 Past Glories, station refreshment rooms - V.R.Webster X021 A veteran of the MSLR - Article, R.M. April 1959 X022 Wadsley bridge station - Article, M.R.C X023 Railway development at Aylesbury BM No 55 X024 Diversions over Woodhead RM Jan 1970 X025 Manchester-Sheffield Electrification - Article, R.M. November 1954 X026 Bowbridge Pilot - Article, R.M. Nov. 1954 X027 Abandonment of SAMR? - letter, Dec. 22nd. 1837 X028 Accident book - Mexboro', 1925 X029 "Transport goes to war" - Book, 1942 X033 Occurrence books, mainly from Mexboro' area - B.R 16 no. 1948-58 X036 Prospectus, Preservation Loughborough - G.C.R 1976 X037 Prop. Closure Sheff.-Pen.-Huddersfield Service - Documents 1981 X038 S.Y.P.T.E. Transport Development Plan - Book 1978 X039 Index - G.C.R.J Vol. VIII X040 Index - G.C.R.J Vol. IX X041 Index - G.C.R.J Vol. X X042 Index - G.C.R articles in R.M X043 Index - G.C.R. LDECR articles in R.M X044 History of Railways around Doncaster - Ms, D.L.Franks X045 "The Plight of the Railways" - Leaflet, G.Huxley X046 "I remember" - Glossop - Booklet X049 "Woodhead Wanderer" railtour - Programme X050 Railtour Doncaster - Lincoln area - Programme X051 The Iron horse comes to town - Article, Appleby-Frodingham news, 1959 X054 The Yarborough Hotel - Notes, from Bradshaw 1853 X055 When service had meaning, The Story of and Early Railwayman's life - D.L Franks X056 Seven ages of Rlys - Ms, D.L. -

The London Gazette, 27 March, 1923

2344. THE LONDON GAZETTE, 27 MARCH, 1923. (Derbyshire Lines), bridge carrying the Scottish Railway (Blackwell Branch) over road from Tibshelf to Sawpit Lane over Fordbridge Lane. -the London and North Eastern Railway Parish of Tibshelf— (Tibshelf Colliery Branch). Bridges carrying the London, Midland (D) Roads under the following bridges:— and Scottish Railway over the roads from Tibshelf to Westhouses and from Tibshelf In the urban district of Sutton-in-Ash- to Morton, bridge carrying the London, fieldt— Midland and Scottish Railway (Tibshelf Bridge carrying the London and North and Pleasley) over Newton Lane, bridges Eastern Railway (Mansfield Railway) over carrying the London and North Eastern Coxmoor Road. Railway (Derbyshire Lines) over Newton Lane and Pit Lane, bridge carrying the In the urban district of Kirkby-in-Ash- London and North Eastern Railway (Tib- field:— shelf Colliery Branch) over Sawpit Lane. Bridge carrying the London, Midland and (E) Railways: — Scottish Railway (Mansfield and Pinxton) over Mill Lane, bridge carrying the In the urban district of Sutton-in-Ash- •London, Midland and Scottish Railway field: — (Bentinck Branch) over Park Lane, bridge Level crossings of the London, Midland carrying the London and North Eastern and Scottish Railway (Nottingham and Railway (Langton Colliery Branch) over Mansfield) in Station Road and Coxmoor the road from Kirkby-in-Ashfield to Road. - Finxton, bridges carrying^ mineral rail- ways at Kirkby Colliery over Southwell In the urban district of Huthwaiter — Lane, bridge carrying mineral railway at Level crossing of mineral railway from Bentinck Colliery over Mill Lane. New Hucknall Colliery in Common Road. In the urban district of Kirkby-in-Ash- In the rural district of Basford: — field: — Parish of Linby— Bridge carrying the London and NortL .Level crossings of the London, Midland Eastern Railway over the road from and Scottish Railway (Nottingham and Linby to Annesley.