King John's Palace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nottinghamshire's Sustainable Community Strategy

Nottinghamshire’s Sustainable Community Strategy the nottinghamshire partnership all together better 2010-2020 Contents 1 Foreword 5 2 Introduction 7 3 Nottinghamshire - our vision for 2020 9 4 How we put this strategy together What is this document based on? 11 How this document links with other important documents 11 Our evidence base 12 5 Nottinghamshire - the timeline 13 6 Nottinghamshire today 15 7 Key background issues 17 8 Nottinghamshire’s economy - recession and recovery 19 9 Key strategic challenges 21 10 Our priorities for the future A greener Nottinghamshire 23 A place where Nottinghamshire’s children achieve their full potential 27 A safer Nottinghamshire 33 Health and well-being for all 37 A more prosperous Nottinghamshire 43 Making Nottinghamshire’s communities stronger 47 11 Borough/District community strategies 51 12 Next steps and contacts 57 Nottinghamshire’s Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-2020 l p.3 Appendices I The Nottinghamshire Partnership 59 II Underpinning principles 61 III Our evidence base 63 IV Consultation 65 V Nottinghamshire - the timeline 67 VI Borough/District chapters Ashfield 69 Bassetlaw 74 Broxtowe 79 Gedling 83 Mansfield 87 Newark and Sherwood 92 Rushcliffe 94 VII Case studies 99 VIII Other relevant strategies and action plans 105 IX Performance management - how will we know that we have achieved our targets? 107 X List of acronyms 109 XI Glossary of terms 111 XII Equality impact assessment 117 p.4 l Nottinghamshire’s Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-2020 1 l Foreword This document, the second community strategy for Nottinghamshire, outlines the key priorities for the county over the next ten years. -

Advisory Visit Rivers Meden and Maun, Thoresby Estate

Advisory Visit Rivers Meden and Maun, Thoresby Estate, Nottinghamshire January 2018 1.0 Introduction This report is the output of a site visit undertaken by Tim Jacklin of the Wild Trout Trust to the Rivers Meden and Maun on the Thoresby Estate, Nottinghamshire on 4th January, 2018. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visit and discussions with Andrew Dobson (River Warden, Thoresby Estate) and Ryan Taylor (Environment Agency). Normal convention is applied throughout the report with respect to bank identification, i.e. the banks are designated left hand bank (LHB) or right hand bank (RHB) whilst looking downstream. 2.0 Catchment / Fishery Overview The River Meden rises to the north of Mansfield and flows east-north- eastwards through a largely rural catchment. The River Maun rises in the conurbation of Mansfield and flows north-eastwards past Ollerton to join the River Meden at Conjure Alders (SK6589872033). The rivers then separate again and re-join approximately 6km downstream near West Drayton (SK7027875118) to form the River Idle (a Trent tributary with its confluence at West Stockwith SK7896894718). Both rivers flow over a geology comprising sandstone with underlying coal measures and there is a history of extensive deep coal mining in the area. Table 1 gives a summary of data collected by the Environment Agency to assess the quality of the rivers for the Water Framework Directive. Both rivers appear to have a similar ecological quality and closer inspection of the categories which make up this assessment reveal that fish and invertebrates were both ‘high’ and ‘good’ for the Meden and Maun respectively in 2016. -

Nottinghamshire County Council Sherwood Living Legend Geo-Environmental Desk Study Report

Nottinghamshire County Council Sherwood Living Legend Geo-environmental Desk Study Report This report is prepared by Atkins Limited for the sole and exclusive use of Nottinghamshire County Council in response to their particular instructions. No liability is accepted for any costs claims or losses arising from the use of this report or any part thereof for any purpose other than that for which it was specifically prepared or by any party other than Nottingham County Council. Nottinghamshire County Council Sherwood Forest Living Legend Geo-environmental Desk Study Report Nottinghamshire County Council Sherwood Living Legend Desk Study Report JOB NUMBER: 5048377 DOCUMENT REF: Sherwood Living Legend Desk Study v2.doc - Draft for Client approval TJC JPB MP NAW Dec-06 1 Final TJC JPB MP NAW Jan-06 Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date Revision Purpose Description Nottinghamshire County Council Sherwood Living Legend Geo-environmental Desk Study Report CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 General 1-1 1.2 Information Reviewed 1-1 1.3 Scope of Works 1-2 2. SITE AREA 2-1 2.1 Site Location 2-1 2.2 Site Description 2-1 2.3 Adjacent Areas 2-1 2.4 Historical Development 2-2 2.5 Archaeology 2-4 2.6 National Monument Records 2-4 3. PUBLISHED GEOLOGICAL INFORMATION 3-1 3.1 Solid and Drift Geology 3-1 3.2 BGS Borehole Logs 3-2 3.3 Hydrology 3-2 3.4 Hydrogeology 3-2 3.5 Mining 3-3 3.6 Radon 3-4 3.7 Additional Geo-environmental Information. 3-4 4. -

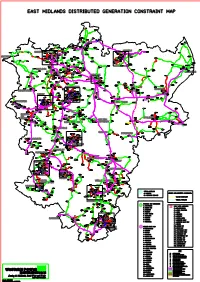

East Midlands Constraint Map-Default

EAST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP MISSON MISTERTON DANESHILL GENERATION NORTH WHEATLEY RETFOR ROAD SOLAR WEST GEN LOW FARM AD E BURTON MOAT HV FARM SOLAR DB TRUSTHORPE FARM TILN SOLAR GENERATION BAMBERS HALLCROFT FARM WIND RD GEN HVB HALFWAY RETFORD WORKSOP 1 HOLME CARR WEST WALKERS 33/11KV 33/11KV 29 ORDSALL RD WOOD SOLAR WESTHORPE FARM WEST END WORKSOPHVA FARM SOLAR KILTON RD CHECKERHOUSE GEN ECKINGTON LITTLE WOODBECK DB MORTON WRAGBY F16 F17 MANTON SOLAR FARM THE BRECK LINCOLN SOLAR FARM HATTON GAS CLOWNE CRAGGS SOUTH COMPRESSOR STAVELEY LANE CARLTON BUXTON EYAM CHESTERFIELD ALFORD WORKS WHITWELL NORTH SHEEPBRIDGE LEVERTON GREETWELL STAVELEY BATTERY SW STN 26ERIN STORAGE FISKERTON SOLAR ROAD BEVERCOTES ANDERSON FARM OXCROFT LANE 33KV CY SOLAR 23 LINCOLN SHEFFIELD ARKWRIGHT FARM 2 ROAD SOLAR CHAPEL ST ROBIN HOOD HX LINCOLN LEONARDS F20 WELBECK AX MAIN FISKERTON BUXTON SOLAR FARM RUSTON & LINCOLN LINCOLN BOLSOVER HORNSBY LOCAL MAIN NO4 QUEENS PARK 24 MOOR QUARY THORESBY TUXFORD 33/6.6KV LINCOLN BOLSOVER NO2 HORNCASTLE SOLAR WELBECK SOLAR FARM S/STN GOITSIDE ROBERT HYDE LODGE COLLERY BEEVOR SOLAR GEN STREET LINCOLN FARM MAIN NO1 SOLAR BUDBY DODDINGTON FLAGG CHESTERFIELD WALTON PARK WARSOP ROOKERY HINDLOW BAKEWELL COBB FARM LANE LINCOLN F15 SOLAR FARM EFW WINGERWORTH PAVING GRASSMOOR THORESBY ACREAGE WAY INGOLDMELLS SHIREBROOK LANE PC OLLERTON NORTH HYKEHAM BRANSTON SOUTH CS 16 SOLAR FARM SPILSBY MIDDLEMARSH WADDINGTON LITTLEWOOD SWINDERBY 33/11 KV BIWATER FARM PV CT CROFT END CLIPSTONE CARLTON ON SOLAR FARM TRENT WARTH -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire Further electoral review December 2005 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 15 2 Current electoral arrangements 19 3 Submissions received 23 4 Analysis and draft recommendations 25 Electorate figures 26 Council size 26 Electoral equality 27 General analysis 28 Warding arrangements 28 a Clipstone, Edwinstowe and Ollerton wards 29 b Bilsthorpe, Blidworth, Farnsfield and Rainworth wards 30 c Boughton, Caunton and Sutton-on-Trent wards 32 d Collingham & Meering, Muskham and Winthorpe wards 32 e Newark-on-Trent (five wards) 33 f Southwell town (three wards) 35 g Balderton North, Balderton West and Farndon wards 36 h Lowdham and Trent wards 38 Conclusions 39 Parish electoral arrangements 39 5 What happens next? 43 6 Mapping 45 Appendices A Glossary and abbreviations 47 B Code of practice on written consultation 51 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

Broomhill Lodge, Off Mansfield Road, Edwinstowe, Notts, NG21 9HG for Sale: £695 Per Calendar Month Or to Let: £695 Per Calendar Month

CHARTERED SURVEYORS AUCTIONEERS VALUERS ESTATE AGENTS barnes EST. 1932 Broomhill Lodge, Off Mansfield Road, Edwinstowe, Notts, NG21 9HG For Sale: £695 Per calendar month or To Let: £695 Per calendar month We are delighted to offer for let this lovely character detached property which is well presented throughout with three bedrooms. Located within a rural position with fabulous views over open farmland. The property stands on a good sized plot with mature gardens and in brief comprises of entrance porch, entrance hall, spacious living room with open coal fire, separate dining room and modern breakfast kitchen (built in oven/hob) with utility room off. To the first floor are three good sized bedrooms plus family bathroom having 3 piece suite and shower over the bath. There is a detached garage and driveway. We would recommend an early viewing so not to be disappointed as these type of properties rarely come onto the market for let. Excellent employers references essential. Please NO PETS. EPC Rating E copy of which is available upon request. Ready for immediate let. Bond £795 VIEWING ACCOMPANIED NOTE:- W A BARNES LLP FEES PAYABLE AS FOLLOWS:- £20 inclusive of VAT (non-refundable) per applicant over the age of 18 years to undertake a credit check. An additional fee of £150 inclusive of VAT per property will be charged when signing the 6 month Assured Shorthold Tenancy Agreement •Lovely Character home • Three good sized bedrooms • Ready for immediate let •Views over open farmland • First floor bathroom/w.c • Please No pets as working •Modern kitchen -oven & hob • Good sized gardens with farm •Two reception rooms • garage and driveway • EPC Rating E • Bond £795 W A BARNES LLP PORTLAND SQUARE SUTTON IN ASHFIELD NOTTINGHAMSHIRE NG17 1DA tel 01623 554084 / 553929 fax 01623 550764 email [email protected] web www.wabarnes.co.uk barnes EST. -

Licensing Committee 3 September 2020

LICENSING COMMITTEE 3 SEPTEMBER 2020 UPDATE ON PERFORMANCE AND ENFORCEMENT MATTERS 1.0 Purpose of Report 1.1 To inform Committee of the activity and performance of the licensing team between 1 January and 30 June 2020 inclusive and to provide Members with details of current going enforcement issues. 2.0 Background 2.1 This report covers the period from 1 January and 30th June 2020 inclusive and sets out the range and number of licence applications during this period. It also highlights any activity required as a result of the applications. Activity Report for 1 January to 30 June 2020 Number Number Number Application Type Comments Received Issued Refused Personal Licence 15 15 Vary the Designated Premise 26 26 Supervisor Transfer of Premise Licence 12 12 Minor Variation 3 3 Variation to Premise Licence 5 5 New Premise licence 7 6 1 pending Change of Premise Name 0 0 Notification of Interest 1 1 Temporary Event Notices 53 53 2.2 By way of comparison, the number of Temporary Event Notices received for the same period last year was 192. 2.3 Enforcement Activity Ongoing Enforcement Activity 1 January and 30 June 2020 Location Summary Of Action Taken So Far Date Case Complaint/Reason Opened For Visit Black Swan Noise complaint 2.1.2020 LEO visited premise and advice given High Street to DPS. Edwinstowe Further noise complaints 2/2/2020 – NG21 9QR DPS issued with written warning The Old Post Office Premise licence 13.1.2020 All in order Kirk Gate check Newark On Trent NG24 1AB The Rutland Arms Premise licence 13.1.2020 All in order 13 Barnby Gate check Newark On Trent NG24 1PX The White Hart Premise licence 13.1.2020 All in order 5 White Hart Yard check Newark On Trent NG24 1DX The Mayze Premise licence 13.1.2020 All in order 7 Castle Gate check Newark On Trent NG24 1AZ Haywood Oaks Golf Premise licence 14.1.2020 2 action points to be followed up. -

Nottinghamshire. 59

DIRECTORY.) NOTTINGHAMSHIRE. EDWINSTOWE • 59 • of the Bishop of Manchester, and held since 1884 by the Sexton, George Markham. Rev. William John Sparrow H.A. of University College, Durham, who resides at Gamston. Lieut.-Col. Henry Letters through Retford, which is the nearest telegraph office, arrive at 8 a.m.; the nearest money order office is Denison R.E., J".P. of Eaton Hall, is lord of the manor and principal landowner. The soil is clayey and sandy loam ; London road, Retford. Wall Letter Box cleared at 5.3() subsoil, marl and limestone. The land is chiefly arable, p.m. on week days only principally growing wheat and barley. The area is 1,519 Public Elementary School, built by the late H. Bridgeman acres of land and 7 of water ; assessable value, £2,961 ; the Simpson esq. for 60 children; average attendance, 50; population in 1901 was 144. Mrs. Whitesmith. mistress Denison Lieut.-Col. Henry R.E., ;r.P. Andersen Charles, farmer Spooner William, farmer Eaton hall Booth John, farmer • Tinker Charles, farmer, Eaton grange COMMERCIAL. Cole William, farmer Wheeldon Robert, farmer Allen Henry 'Villiam, cowkeeper Curtis Edwin & John, fanners EDINGLEY is a pleasant village and parish, near the chapel, erected in 1838, was re-seated and a new porch river Greet, on the road between Southwell and Mans- added in 1898, and affords sittings for 80 persons. The field, with a station called Kirklington and Edingley on charities amount to £7 8s. yearly. The Manor House is. the Mansfield and Newark line of the Midland railway, one an old building, now occupied as a farmhouse. -

Southwell and Nottingham

Locality Church Name Parish County Diocese Date Grant reason ALLENTON Mission Church ALVASTON Derbyshire Southwell 1925 New Church ASKHAM St. Nicholas ASKHAM Nottinghamshire Southwell 1906-1908 Enlargement ATTENBOROUGH St. Mary Magdalene ATTENBOROUGH Nottinghamshire Southwell 1948-1950 Repairs ATTENBOROUGH St. Mary Magdalene ATTENBOROUGH Nottinghamshire Southwell 1956-1957 Repairs BALDERTON St. Giles BALDERTON Nottinghamshire Southwell 1930-1931 Reseating/Repairs BAWTRY St. Nicholas BAWTRY Yorkshire Southwell 1900-1901 Reseating/Repairs BLIDWORTH St. Mary & St. Laurence BLIDWORTH Nottinghamshire Southwell 1911-1914 Reseating BLYTH St. Mary & St. Martin BLYTH Derbyshire Southwell 1930-1931 Repairs BOLSOVER St. Mary & St. Laurence BOLSOVER Derbyshire Southwell 1897-1898 Rebuild BOTHAMSALL St. Peter BOTHAMSALL Nottinghamshire Southwell 1929-1930 Repairs BREADSALL All Saints BREADSALL Derbyshire Southwell 1914-1916 Enlargement BRIDGFORD, EAST St. Peter BRIDGFORD, EAST Nottinghamshire Southwell 1901-1905 Repairs BRIDGFORD, EAST St. Peter BRIDGFORD, EAST Nottinghamshire Southwell 1913-1916 Repairs BRIDGFORD, EAST St. Peter BRIDGFORD, EAST Nottinghamshire Southwell 1964-1969 Repairs BUXTON St. Mary BUXTON Derbyshire Southwell 1914 New Church CHELLASTON St. Peter CHELLASTON Derbyshire Southwell 1926-1927 Repairs CHESTERFIELD Christ Church CHESTERFIELD, Holy Trinity Derbyshire Southwell 1912-1913 Enlargement CHESTERFIELD St. Augustine & St. Augustine CHESTERFIELD, St. Mary & All Saints Derbyshire Southwell 1915-1931 New Church CHILWELL Christ Church CHILWELL Nottinghamshire Southwell 1955-1957 Enlargement CLIPSTONE All Saints, New Clipstone EDWINSTOWE Nottinghamshire Southwell 1926-1928 New Church CRESSWELL St. Mary Magdalene CRESSWELL Derbyshire Southwell 1913-1914 Enlargement DARLEY St. Mary the Virgin, South Darley DARLEY, St. Mary the Virgin, South Darley Derbyshire Southwell 1884-1887 Enlargement DERBY St. Dunstan by the Forge DERBY, St. James the Great Derbyshire Southwell 1889 New Church DERBY St. -

JULY 2019 Plan Review - Allocations & Development Management Issues Paper

PLAN REVIEW REVIEW OF THE NEWARK & SHERWOOD LOCAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK CORE STRATEGY & ALLOCATIONS ALLOCATIONS & DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT ISSUES PAPER JULY 2019 Plan Review - Allocations & Development Management Issues Paper 1.0 Introduction 1.1 The District Council has been reviewing the various elements of Newark & Sherwood’s Development Plan over the past four years. The plan is now made up of the Amended Core Strategy (Adopted 7th March 2019), the Allocations & Development Management DPD (Adopted 2013) and ‘made’ Neighbourhood Plans’ (currently including those for Farnsfield, Fernwood, Kings Clipstone, Southwell and Thurgarton). 1.2 Following the Adoption of the Amended Core Strategy DPD earlier this year, the remaining elements of the Plan Review, which are made up of the allocations and development management policies contained within the Allocations and Development Management DPD will now need to be progressed; along with a new strategy and allocations to meet future housing need for Gypsy & Travellers in the District. It should be noted that as part of updating the general housing and employment section of the DPD we are not intending to identify any other new allocations (see section 8). 1.3 It should also be noted that in July 2018 the Government published an updated National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), which was subject to further clarifications and re-issued in February 2019. It is therefore necessary to ensure that all elements of the Development Plan continue to be in compliance with national policy. 1.4 The remainder of this paper provides a position statement on the Plan Review: Section 2 considers the new NPPF and the various issues of conformity with regard to the Adopted Amended Core Strategy and the Development Management Policies that are still being considered as part of the Plan Review. -

Edwinstowe Archaeoastronomical and Topographic Survey 2017

Archaeoastronomical and Topographic Survey at St Mary’s Church, Edwinstowe in Sherwood Forest Nottinghamshire. (SK 62519 66941). Archaeoastronomical and Topographic Survey Report Andy Gaunt Mercian Archaeological Services CIC 06/09/2017 Ref: EDWINGAU17001 Report MAS030 © Mercian Archaeological Services 2017. Mercian Archaeological Services CIC is a limited company registered in England and Wales. Company Reg No. 08347842. 1 © Mercian Archaeological Services CIC 2017. www.mercian-as.co.uk Archaeoastronomical and Topographic Survey at St Mary’s Church, Edwinstowe in Sherwood Forest Nottinghamshire. Archaeoastronomical and Topographic Survey Report (SK 62519 66941). Andy Gaunt MA BSc (Hons) CertHE FGS FRGS Mercian Archaeological Services CIC MAS030 Title: Archaeoastronomical and Topographic Survey at St Mary’s Church, Edwinstowe in Sherwood Forest Nottinghamshire. Author: Andy Gaunt MA BSc (Hons) CertHE FGS FRGS Derivation: - Date of Origin: 01/02/2017 Version Number: 2.2 Date of Last Revision: 06/09/2017 Revisers: Status: Final Summary of Changes: Bibliography edited Mercian Project Identifier: EDWINGAU17001 Client: Mercian Archaeological Services CIC Checked / Approved for Sean Crossley Release by: MA PGDip BSc (Hons) 2 © Mercian Archaeological Services CIC 2017. www.mercian-as.co.uk Archaeoastronomical and Topographic Survey at St Mary’s Church, Edw instowe in Sherw ood Forest, Nottinghamshire. 2017. Contents Page 1. Summary 6 2. Project Location, Topography and Geology 13 3. Archaeological and Historical Background 14 4. Research Aims and Objectives 22 5. Methodology 24 6. Results 37 7. Discussion 43 8. Bibliography 74 9. Acknowledgments 78 10. Disclaimer 78 Appendix 80 3 © Mercian Archaeological Services CIC 2017. www.mercian-as.co.uk Archaeoastronomical and Topographic Survey at St Mary’s Church, Edw instowe in Sherw ood Forest, Nottinghamshire. -

Housing Background Paper Addendum 2 September 2017

Housing Background Paper Addendum 2 September 2017 CONTENTS Page Introduction 3 Local Planning Document Submission and Hearing Sessions 3 Five Year Land Supply update 2017 4 Conclusion 12 Appendix A: Housing Supply 2011-2028 13 Appendix B: Deliverability Notes 16 Appendix C: Schedule of Deliverable and Developable Sites in the Plan Period 2011 to 2028 19 Appendix D: Detailed Housing Trajectory 42 Appendix E: Windfall Allowance 46 Appendix E1: Sites which comprise the small windfall completions 2007 to 2017 53 Appendix E2: Sites that were not previously in the SHLAA database 2011 to 2017 63 2 Introduction 1.1 This Addendum 2 to the Housing Background Paper (May 2016) (LPD/BACK/01) supersedes the following:- Housing Background Paper Addendum (December 2016) (EX/22); Revised Housing Background Paper Addendum (March 2017) (EX/104); Update to the Revised Housing Background Paper Addendum – April 2017 (April 2017) (EX/111); and Further Revised Housing Background Paper Addendum (May 2017) (EX/102A). 1.2 Appendix A provides the full breakdown of housing supply to meet the housing requirement of 7,250 homes. 1.3 Appendix B refers to the deliverability assumptions and includes a map of the sub market areas. This appendix updates Appendix A of the Housing Background Paper (May 2016). 1.4 Appendix C provides the list of sites that make up the five year supply (i.e. 2017 to 2022) and the housing supply for the plan period (i.e. 2011 to 2028). Sites that have been completed during 2011 and 2017 are not listed individually, rather a figure for total completions is provided.