Swiss International Cooperation Annual Report 2015 CONTENT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

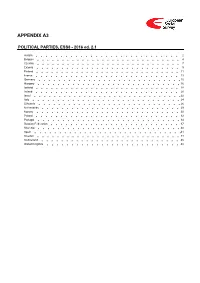

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Alternatives in a World of Crisis

ALTERNATIVES IN A WORLD OF CRISIS GLOBAL WORKING GROUP BEYOND DEVELOPMENT MIRIAM LANG, CLAUS-DIETER KÖNIG EN AND ADA-CHARLOTTE REGELMANN (EDS) ALTERNATIVES IN A WORLD OF CRISIS INTRODUCTION 3 I NIGERIA NIGER DELTA: COMMUNITY AND RESISTANCE 16 II VENEZUELA THE BOLIVARIAN EXPERIENCE: A STRUGGLE TO TRANSCEND CAPITALISM 46 III ECUADOR NABÓN COUNTY: BUILDING LIVING WELL FROM THE BOTTOM UP 90 IV INDIA MENDHA-LEKHA: FOREST RIGHTS AND SELF-EMPOWERMENT 134 V SPAIN BARCELONA EN COMÚ: THE MUNICIPALIST MOVEMENT TO SEIZE THE INSTITUTIONS 180 VI GREECE ATHENS AND THESSALONIKI: BOTTOM-UP SOLIDARITY ALTERNATIVES IN TIMES OF CRISIS 222 CONCLUSIONS 256 GLOBAL WORKING GROUP BEYOND DEVELOPMENT Miriam Lang, Claus-Dieter König and Ada-Charlotte Regelmann (Eds) Brussels, April 2018 SEEKING ALTERNATIVES BEYOND DEVELOPMENT Miriam Lang and Raphael Hoetmer ~ 2 ~ INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION ~ 3 ~ This book is the result of a collective effort. In fact, it has been written by many contribu- tors from all over the world – women, men, activists, and scholars from very different socio-cultural contexts and political horizons, who give testimony to an even greater scope of social change. Their common concern is to show not only that alternatives do exist, despite the neoliberal mantra of the “end of history”, but that many of these alternatives are currently unfolding – even if in many cases they remain invisible to us. This book brings together a selection of texts portraying transformative processes around the world that are emblematic in that they been able to change their situated social realities in multiple ways, addressing different axes of domination simultaneously, and anticipating forms of social organization that configure alternatives to the commodi- fying, patriarchal, colonial, and destructive logics of modern capitalism. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

Swiss Political System Introduction

SWIss POLITICAL SYSTEM INTRODUCTION Switzerland is a small country in Western roots date back to 1291, whereas the Europe with 7.8 million inhabitants. With modern nation state was founded in 1848. its 41,285 square kilometres, Switzerland Switzerland’s population is 1.5 % of Europe; accounts for only 0.15 % of the world’s total however, the country is economically com- surface area. It borders Germany in the paratively strong. north, Austria and Liechtenstein in the east, Italy in the south and France in the west. The population is diverse by language as well as by religious affiliation. Its historical FEDERAL SYSTEM Switzerland is a federation; the territory is divided into 26 cantons. The cantons themselves are the aggregate of 2,600 municipalities (cities and villages). ELECTIONS AND The political system is strongly influenced by DIRECT DEMOCRACY direct participation of the people. In addition to the participation in elections, referenda and ini- tiatives are the key elements of Switzerland’s well-established tradition of direct democracy. CONSENSUS The consensus type democracy is a third char- DEMOCRACY acteristic of Swiss political system. The institu- tions are designed to represent cultural diver- sity and to include all major political parties in a grand-coalition government. This leads to a non- concentration of power in any one hand but the diffusion of power among many actors. COMPARATIVE After the elaboration of these three important PERSPECTIVES elements of the Swiss political system, a com- parative perspective shall exemplify the main differences of the system vis-à-vis other western democracies CONTENTS PUBliCATION DaTA 2 FEDERAL SYSTEM Switzerland is a federal state with three ■■ The decentralised division of powers is political levels: the federal govern- also mirrored in the fiscal federal structure ment, the 26 cantons and around 2,600 giving the cantonal and municipal level own municipalities. -

Pandemic Populism”: the COVID-19 Crisis and Anti-Hygienic Mobilisation of the Far-Right

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article The “New Normal” and “Pandemic Populism”: The COVID-19 Crisis and Anti-Hygienic Mobilisation of the Far-Right Ulrike M. Vieten School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT7 1NN, UK; [email protected] Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 15 September 2020; Published: 22 September 2020 Abstract: The paper is meant as a timely intervention into current debates on the impact of the global pandemic on the rise of global far-right populism and contributes to scholarly thinking about the normalisation of the global far-right. While approaching the tension between national political elites and (far-right) populist narratives of representing “the people”, the paper focuses on the populist effects of the “new normal” in spatial national governance. Though some aspects of public normality of our 21st century urban, cosmopolitan and consumer lifestyle have been disrupted with the pandemic curfew, the underlying gendered, racialised and classed structural inequalities and violence have been kept in place: they are not contested by the so-called “hygienic demonstrations”. A digital pandemic populism during lockdown might have pushed further the mobilisation of the far right, also on the streets. Keywords: far-right populism; structural violence; national elites; normalisation; COVID-19; “anti-hygienic” demonstrations in Germany 1. Introduction1 In 1953, Hannah Arendt argued that the subject of a totalitarian state is the individual, who cannot distinguish between fact and fiction and, in consequence, the totalitarian threat could be witnessed to the degree to which the individuals’ capacity of differentiating true from false information is undermined (Arendt 1953). -

MAPPING the EUROPEAN LEFT Socialist Parties in the EU ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG NEW YORK OFFICE by Dominic Heilig Table of Contents

MAPPING THE EUROPEAN LEFT Socialist Parties in the EU ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG NEW YORK OFFICE By Dominic Heilig Table of Contents The Rise of the European Left. By the Editors 1 Mapping the European Left Socialist Parties in the EU 2 By Dominic Heilig 1. The Left in Europe: History and Diversity 2 2. Syriza and Europe’s Left Spring 10 3. The Black Autumn of the Left in Europe: The Left in Spain 17 4. DIE LINKE: A Factor for Stability in the Party of the European Left 26 5. Strategic Tasks for the Left in Europe 33 Published by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, New York Office, April 2016 Editors: Stefanie Ehmsen and Albert Scharenberg Address: 275 Madison Avenue, Suite 2114, New York, NY 10016 Email: [email protected]; Phone: +1 (917) 409-1040 With support from the German Foreign Office The Rosa Luxemburg Foundation is an internationally operating, progressive non-profit institution for civic education. In cooperation with many organizations around the globe, it works on democratic and social participation, empowerment of disadvantaged groups, alternatives for economic and social development, and peaceful conflict resolution. The New York Office serves two major tasks: to work around issues concerning the United Nations and to engage in dialogue with North American progressives in universities, unions, social movements, and politics. www.rosalux-nyc.org The Rise of the European Left The European party system is changing rapidly. As a result of the ongoing neoliberal attack, the middle class is shrinking quickly, and the decades-old party allegiance of large groups of voters has followed suit. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Going to Extremes Politics After Financial Crises, 1870–2014

European Economic Review ∎ (∎∎∎∎) ∎∎∎–∎∎∎ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect European Economic Review journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/eer Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870–2014 Manuel Funke a, Moritz Schularick b,d,e,n, Christoph Trebesch c,d,e a Free University of Berlin, John F. Kennedy Institute, Department of Economics, Germany b University of Bonn, Department of Economics, Germany c University of Munich, Department of Economics, Germany d CEPR, United Kingdom e CESIfo, Germany article info abstract Article history: Partisan conflict and policy uncertainty are frequently invoked as factors contributing to Received 9 March 2016 slow post-crisis recoveries. Recent events in Europe provide ample evidence that the Accepted 26 March 2016 political aftershocks of financial crises can be severe. In this paper we study the political fall-out from systemic financial crises over the past 140 years. We construct a new long- JEL classification: run dataset covering 20 advanced economies and more than 800 general elections. Our D72 key finding is that policy uncertainty rises strongly after financial crises as government G01 majorities shrink and polarization rises. After a crisis, voters seem to be particularly E44 attracted to the political rhetoric of the extreme right, which often attributes blame to minorities or foreigners. On average, far-right parties increase their vote share by 30% Keywords: after a financial crisis. Importantly, we do not observe similar political dynamics in normal Financial crises recessions or after severe macroeconomic shocks that are not financial in nature. Economic voting & Polarization 2016 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Policy uncertainty 1. -

Political Stability and the Fragmentation of Online Publics in Multilingual States Working Paper

Political stability and the fragmentation of online publics in multilingual states Working paper Francesco Bailo The University of Sydney [email protected] 16th September 2016 Abstract In this paper I compare users’ interactions on Facebook pages of parties and politicians in four different European multilingual countries: Switzerland, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Ukraine. The focus is on measuring the political and linguistic divide of online publics and their association with measures of political stability of the respective countries. The four countries are interesting case studies because although all ethnolinguistic heterogeneous produce very different levels of political stability. In political science literature, fragmentation and polarisation are often read as malaises and possibly facilitated and fomented by Internet communication technologies. As the theory goes, the fragmentation of deliberating publics, or the absence of cross-groups communication channels because of assortative tendencies, might exacerbate polarisation by reducing the exposure to diverse views and moving members of groups towards more extreme positions, reducing political stability and increasing conflictuality. But the results presented in this paper suggest that ethnolinguistic fragmentation is not associated with stability and in fact less politically stable countries might have more integrated online publics. Keywords: Facebook; Belgium; Ukraine; Switzerland; Bosnia; Online politics; Political stability; Exponential Random Graph Models; Networks Contents 1 Political and ethnolinguistic fragmentation . 2 2 Factionalisation, group grievance and political stability in Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegov- ina, Ukraine and Switzerland . 3 3 Data ................................................ 4 3.1 Data collection . 4 3.2 Country demographics and Facebook adoption . 5 1 Political stability and the fragmentation of online publics in multilingual states 3.3 Political position of parties . -

Contemporary Far Left Parties in Europe from Marxism to the Mainstream?

Internationale Politikanalyse International Policy Analysis Luke March Contemporary Far Left Parties in Europe From Marxism to the Mainstream? The far left is increasingly a stabilised, consolidated and permanent ac- tor on the EU political scene, although it remains absent in some countries and in much of former communist Eastern Europe. The far left is now ap- proaching a post–Cold War high in several countries. The far left is becoming the principal challenge to mainstream social democratic parties, in large part because its main parties are no longer extreme, but present themselves as defending the values and policies that social democrats have allegedly abandoned. The most successful far left parties are those that are pragmatic and non-ideological, and have charismatic leaders. The most successful strate- gies include an eco-socialist strategy that emphasises post-material white- collar concerns and populist anti-elite mobilisation. The contemporary so- cio-economic and political environment within the EU is likely to increase the future appeal of a populist strategy above all. Policy-makers should not seek to demonise or marginalise far left par- ties as a rule; such policies are likely to backfire or be successful only in the short term, especially by increasing the tendency to anti-establishment populist mobilisation. A successful strategy towards the far left would involve engaging and cooperating with its most pragmatic actors where necessary, whilst seek- ing to address the fundamental socio-economic and political concerns that provide the long-term basis for its success. Imprint Orders All texts are available online: NOVEMBER 2008 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung www.fes.de/ipa International Policy Analysis International Policy Analysis The views expressed in this publication Division for International Dialogue z. -

Switzerland: the Green Party and the Alternative Greens

Switzerland: the Green Party and the Alternative Greens Michael Brändle and Andreas Ladner erscheint in: RIHOUX, Benoît, LUCARDIE, Paul, and FRANKLAND, E. Gene (eds) (forthcoming), Green Parties in Transition : the End of Grass-Roots Democracy?, Albany, State University of New York Press. A) Emergence and development of the Swiss green parties Green and alternative-left movements and parties claim to be different from established parties. In respect to their organizational structure and their intra-party decision making processes they refer to the notions of grass-roots or direct democracy and differ from established hierarchical (elite- oriented) and centralized party organizations. As Poguntke states for the German Greens, grass- roots democracy as a normative goal means “that lower organizational levels should have as much autonomy as possible and that individual party members (or supporters) should have a maximum of participatory opportunities at all organizational levels and in the parliamentary activities of the party” (Poguntke 1994: 4). The organizational implementation of these principles is generally associated with decentralized structures and formalized direct democratic decision making processes as well as rules of democratic control (Fogt 1984: 97). The translation of participatory elements into organizational structures and rules may be realized in many different ways, but always occurs within specific institutional conditions that impede or favour their realization. The case of the German Greens shows that the full realization of grass- roots democratic ideals is hindered by systemic constraints as for instance immanent mechanisms of the parliamentary system (Poguntke 1987: 630). In contrast, the Swiss political system seems to anticipate quite a few of the main goals of grass-roots democracy: the decentralized structure including a high degree of autonomy of the lower state units, the far reaching direct democratic means of participation, and consociational decision making as a core feature of the political system and the political culture. -

Radical Left in Europe 2017

Radical Left in Europe 2017 Documentation of contributions about the radical Left in Europe in addition of the Work- shop of Transform and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation July 7- 9 2016 Cornelia Hildebrandt/Luci Wagner 30.07.2017 DOCUMENTATION: RADIKAL LEFT IN EUROPE AND BERLIN SEMINAR 2016 2 Content Preface ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Hildebrandt, Cornelia and Baier, Walter ............................................................................................... 10 Radical Left Transnational Organisation Brie, Michael and Candeias, Mario........................................................................................................ 29 The Return of Hope. For an offensive double strategy Dellheim, Judith ..................................................................................................................................... 42 On scenarios of EU development Jokisch, René ......................................................................................................................................... 54 Reconstruction of the EU legislation and Institutions with consequences for the Left Cabanes, de Antoine ............................................................................................................................. 57 The metamorphosis of the Front National Lichtenberger, Hanna ...........................................................................................................................