“Notre Place”: Franco-Ontarians' Search for a Musical Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIERSFIERS !! Des Tonnes D'idées D'activités Pour Célébrer Notre Fierté Pendant Toute L'année…

FIERSFIERS !! Des tonnes d'idées d'activités pour célébrer notre fierté pendant toute l'année… ! La rentrée (septembre) 2 ! La Fête du drapeau franco-ontarien (25 septembre) 4 ! La musique, nos artistes et la Nuit sur l'étang (octobre) 12 ! La Journée des enseignantes et enseignants (octobre) 21 ! La Journée des enfants (novembre) 24 ! La création de la FESFO et « l'Organizzaction! » (novembre) 25 ! Le Jour du souvenir (11 novembre) 29 ! La Fête de la Sainte-Catherine (25 novembre) 30 ! La Journée contre la violence faite aux femmes (6 décembre) 33 ! Le Temps des Fêtes (décembre) 38 ! Une « Bonne année » remplie de fierté! (janvier) 41 ! La Journée anti-toxicomanie (janvier) 46 ! La Victoire sur le règlement 17 (février) 47 ! Le Mois de l'Histoire des Noirs (février) 50 ! La Saint-Valentin (14 février) 52 ! Le Carnaval (février) 53 ! La Semaine de la francophonie (mi-mars) 57 ! La Chaîne humaine SOS Montfort (20 au 22 mars) 63 ! La Journée « Mettons fin au racisme! » (21 mars) 64 ! Le Théâtre et la scène franco-ontarienne (avril) 66 ! La Journée de l'environnement (avril) 68 ! La Semaine du bénévolat (avril) 69 ! La Semaine de l'Éducation (début mai) 70 ! La Semaine des Jeux franco-ontariens (mi-mai) 72 ! La Fête de Dollard (jour de congé férié en mai) 75 ! L'aventure touristique en Ontario français (juin) 77 ! L'arrivée de l'été! (21 juin) 80 ! La Fête de la Saint-Jean Baptiste (24 juin) 81 ! Les « Au revoir »… (fin juin) 82 ! Remerciements 84 AUTRES INFORMATIONS À DÉCOUVRIR ! ! Explications historiques des fêtes du calendrier : Rubrique -

'Sbodpqipof Xffl Foejoh Xjui Nvtjd Boe Nfssjnfou

)&DEHJ>;HDB?<;"<H?:7O"C7H9>()"(&&- MEM Showtimes for the week of Mar. 23rd, 2007 to Mar. 29th, 2007 Zodiac (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 8:00 MON - THU: 8:00 'SBODPQIPOFXFFL Fido (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 3:05 9:20 MON - THU: 9:20 Reno 911: Miami (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 3:15 9:15 MON - THU: 9:15 Norbit (PG) FRI & SAT & SUN: 1:05 7:05 FOEJOHXJUINVTJD MON - THU: 7:05 Breach (PG) FRI & SAT & SUN: 12:50 7:00 MON - THU: 7:00 Because I Said So (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 6:55 9:10 MON - THU: 6:55 9:10 BOENFSSJNFOU Black Snake Moan (14A) FRI & SAT & SUN: 3:20 9:00 MON - THU: 9:00 Music And Lyrics (PG) BY BILL BRADLEY Les Breastfeeders are a FRI & SAT & SUN: 12:55 6:45 MON - THU: 6:45 [email protected] Montreal group guaranteed Stomp The Yard (PG) FRI & SAT & SUN: 9:05 La Nuit sur l’etang is, and to rock the house. Many of MON - THU: 9:05 Happily Never After (G) always has been, a showcase their songs have made it on to FRI & SAT & SUN: 12:45 3:00 Night At The Museum (G) for francophone culture. the charts and its two videos FRI & SAT & SUN: 1:10 3:25 6:50 MON - THU: 6:50 La Nuit sur l’etang has been enjoyed strong rotation on Happy Feet (PG) Musique Plus. Their song FRI & SAT & SUN: 12:45 3:10 exciting audiences with the best of francophone RAINBOW CENTRE Best Movie Deal in Rainbow Country! entertainment for 34 MATINEES, SENIORS, CHILDREN $4.24 years, says president ADULTS EVENINGS $6.50 $4.24 TUESDAYS Gino St. -

Université D'ottawa University of Ottawa

Université d'Ottawa University of Ottawa UNIVERSITÉ D'OTTAWA DEPARTEMENT DE MUSIQUE Musique populaire et identité kanco-ontmiennes La Nuit sur l'étang Marie-Hélène Pichett e (Ci Thèse présentée à l'École des études supérieures et de la recherche en vue de l'obtention du grade de Maîtrise ès arts (ethnomusicohgie) Février 2000 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services biblographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. me Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KiA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothéque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fk., de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Remerciements Cette thèse n'aurait pas été possible sans l'aide d'un grand nombre de personnes qui, par leur temps, leur collaboration ou leur soutien, ont contriiué, de près ou de loin, à la réalisation de ce travail. Je tiens d'abord à remercier mes infomteus, Paul Demas, Nicolas Doyon, Jacqueline Gauthier, Réjean Grenier, Jean-Guy Labeile, Jem-Marc Lalonde, Fritz Larivièxq Robert Paquette et Gaston Tremblay, qui se sont déplacés ou m'ont généreusement accueillie dans leur demeure ou leur milieu de travail pour répondre à mes questions. -

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to The

Brief Regarding the Future of Regional News Submitted to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage By The Fédération nationale des communications – CSN April 18, 2016 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The role of the media in our society ..................................................................................................................... 7 The informative role of the media ......................................................................................................................... 7 The cultural role of the media ................................................................................................................................. 7 The news: a public asset ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Recent changes to Quebec’s media landscape .................................................................................................. 9 Print newspapers .................................................................................................................................................... -

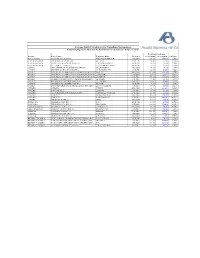

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures As Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit

Average Daily Circulation for Canadian Newspapers Preliminary Figures as Filed with the Audit Bureau of Circulations -- Subject to Audit Total Paid Circulation Province City (County) Newspaper Name Frequency As of 9/30/09 As of 9/30/08 % Change NOVA SCOTIA HALIFAX (HALIFAX CO.) CHRONICLE-HERALD AVG (M-F) 108 182 110 875 -2,43% NEW BRUNSWICK FREDERICTON (YORK CO.) GLEANER MON-FRI 20 863 21 553 -3,20% NEW BRUNSWICK MONCTON (WESTMORLAND CO.) TIMES-TRANSCRIPT MON-FRI 36 115 36 656 -1,48% NEW BRUNSWICK ST. JOHN (ST. JOHN CO.) TELEGRAPH-JOURNAL MON-FRI 32 574 32 946 -1,13% QUEBEC CHICOUTIMI (LE FJORD-DU-SAGUENAY) LE QUOTIDIEN AVG (M-F) 26 635 26 996 -1,34% QUEBEC GRANBY (LA HAUTE-YAMASKA) LA VOIX DE L'EST MON-FRI 14 951 15 483 -3,44% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE -DE-MONTREAL)GAZETTE AVG (M-F) 147 668 143 782 2,70% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LE DEVOIR AVG (M-F) 26 099 26 181 -0,31% QUEBEC MONTREAL (COMMUNAUTE-URBAINE- DE-MONTREAL)LA PRESSE AVG (M-F) 198 306 200 049 -0,87% QUEBEC QUEBEC (COMMUNAUTE- URBAINE-DE-QUEBEC) LE SOLEIL AVG (M-F) 77 032 81 724 -5,74% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) LA TRIBUNE AVG (M-F) 31 617 32 006 -1,22% QUEBEC SHERBROOKE (SHERBROOKE CO.) RECORD MON-FRI 4 367 4 539 -3,79% QUEBEC TROIS-RIVIERES (FRANCHEVILLE CEN. DIV. (MRC) LE NOUVELLISTE AVG (M-F) 41 976 41 886 0,21% ONTARIO OTTAWA CITIZEN AVG (M-F) 118 373 124 654 -5,04% ONTARIO OTTAWA-HULL LE DROIT AVG (M-F) 35 146 34 538 1,76% ONTARIO THUNDER BAY (THUNDER BAY DIST.) CHRONICLE-JOURNAL AVG (M-F) 25 495 26 112 -2,36% ONTARIO TORONTO GLOBE AND MAIL AVG (M-F) 301 820 329 504 -8,40% ONTARIO TORONTO NATIONAL POST AVG (M-F) 150 884 190 187 -20,67% ONTARIO WINDSOR (ESSEX CO.) STAR AVG (M-F) 61 028 66 080 -7,65% MANITOBA BRANDON (CEN. -

Prescribed by Law/Une Règle De Droit©

PRESCRIBED BY LAW/UNE RÈGLE © DE DROIT ∗ ROBERT LECKEY In Multani, the Supreme Court of Canada’s Dans l’affaire Multani sur le port du kirpan, les kirpan case, judges disagree over the proper juges de la Cour suprême du Canada exprimèrent approach to reviewing administrative action under leur désaccord au sujet de l’approche adéquate au the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The contrôle des décisions administratives en vertu de la concurring judges questioned the leading judgment, Charte canadienne des droits et libertés. Les juges Slaight Communications, on the basis that it is minoritaires remirent en question l’arrêt Slaight inconsistent with the French text of section 1. This Communications, arguant que ce précédent était disagreement stimulates reflections on language and incompatible avec la version française de l’article culture in Canadian constitutional and administrative premier de la Charte. Ce désaccord soulève des law. A reading of both language versions of section 1, réflexions au sujet du rôle du langage et de la culture Slaight, and the critical scholarship reveals a au sein du droit constitutionnel et administratif linguistic dualism in which scholars read one version canadien. Une lecture des versions anglaise et of the Charter and of the judgment and write about française de l’article premier et de Slaight et de la them in that language. The separate streams doctrine revèle un dualisme linguistique par lequel undermine the idea of a shared, bilingual public law. les juristes lisent une seule version de la Charte et du Yet the differences exceed language. The article jugement et les commentent en cette même langue. -

Sherbrooke : Sa Place Dans La Vie De Relations Des Cantons De L’Est Pierre Cazalis

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 05:11 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Sherbrooke : sa place dans la vie de relations des Cantons de l’Est Pierre Cazalis Volume 8, numéro 16, 1964 Résumé de l'article Because they are due to economic contingencies rather than to unfavourable URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/020498ar natural conditions, present-day regional disparities compel the geographer to DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/020498ar modify his concept of the region. Whereas in the past the region was considered essentially as a physical entity, to many authors it appears today to Aller au sommaire du numéro be « a functional area, based on communication and exchange, and as such defined less by its limits than by its centre » (Juillard). It is this concept which will be used in regional planning. Éditeur(s) Taking the city of Sherbrooke as a nodal centre, the author attempts to define such a region through an analysis and graphical representation of the Département de géographie de l'Université Laval complementary roles in influence and attraction played by the city in the fundamental aspects of employment, trade, finance, education, ISSN communication, health and government. Although it is already well-developed in the secondary sector, with more than 9,000 workers employed in industry 0007-9766 (imprimé) and an annual production worth more than $100 million, Sherbrooke bas a 1708-8968 (numérique) power of attraction and influence which is due essentially to its tertiary sector : wholesale trade, insurance, education, communication. Ac-cording to the Découvrir la revue criteria mentioned above, the area dominated by Sherbrooke includes the whole of the following counties : Sherbrooke, Stanstead, Richmond, Wolfe and Compton ; and the greater part of Frontenac, Mégantic, Artbabaska, Citer cet article Drummond and Brome counties. -

Le Passage Du Canada Français À La Francophonie Mondiale : Mutations Nationales, Démocratisation Et Altruisme Au Mouvement Richelieu, 1944 – 1995

Le passage du Canada français à la Francophonie mondiale : mutations nationales, démocratisation et altruisme au mouvement Richelieu, 1944 – 1995 par Serge Dupuis A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Serge Dupuis 2013 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Je déclare par la présente que je suis le seul auteur de cette thèse. Il s’agit d’une copie réelle de la thèse, y compris toute révision finale requise, telle qu’acceptée par les examinateurs. Je comprends que ma thèse pourrait être rendue disponible électroniquement au public. Serge Dupuis 30 August 2013 ii Abstract / Résumé This thesis argues that French Canada did not simply fragment into regional and provincial identities during the 1960s and 1970s, but was also kept afloat by the simultaneous emergence of a francophone supranational reference. In order to demonstrate this argument, I have studied the archives of the Richelieu movement, a French Canadian society founded in 1944 in Ottawa, which was internationalized in the hopes of developing relationships amongst the francophone elite around the world. This thesis also considers the process of democratization and the evolution of conceptions of altruism within the movement, signalling again the degree to which the global project of the Francophonie captivated the spirits of Francophones in North America, but also in Europe, the Caribbean and Africa. -

The FCHS NEWSLETTER President A

The FCHS NEWSLETTER www.frenchcolonial.org President A. J. B. (John) Johnston April 2002 Newsletter Parks Canada, Atlantic Service Center 1869 Upper Water St. 2nd Floor, Pontac House Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 1S9 Tel. 902-426-9805 Fax. 902-426-7012 e-mail: [email protected] This issue of the Newsletter is packed with useful information, including the preliminary Past President Dale Miquelon program for the upcoming New Haven meeting. History Department Please send in your registration forms as soon as University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Sask. S7N 0W0 possible so that the conference organizers can plan Tel. 306-242-1745 accordingly for the Mystic Seaport trip and the Fax 306-966-5852 Saturday banquet. Also included in this issue are e-mail: [email protected] the minutes from our last meeting in Detroit, Vice President notices, a message from the President, a final update Robert S. DuPlessis Department of History on the transition from the Proceedings to a journal Swarthmore College format, and a call for papers for the 2003 meeting to 500 College Ave be held in Toulouse, France. Swarthmore, PA 19081-1397 Tel. 610-328-8131 Also enclosed with this edition of the Fax 610-328-8171 Newsletter is an advertisement insert for two e-mail [email protected] volumes of potential interest published by the Secretary-Treasurer University of Rochester Press. William Newbigging Finally, the webpage continues to attract Department of History Algoma University College interest from potential new members and contains a 1520 Queen Street East useful list of links. As usual, information for Sault Ste. -

030140236.Pdf

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ À L'UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À TROIS-RIVIÈRES COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN ÉTUDES QUÉBÉCOISES PAR CATHERINE LAMPRON-DESAULNIERS LA VIE CULTURELLE À TROIS-RIVIÈRES DANS LES ANNÉES 1960 : DÉMOCRATISA TI ON DE LA CUL TURE, DÉMOCRATIE CUL TU REL LE ET CUL TURE JEUNE. HISTOIRE D'UNE TRANSITION MARS 2010 Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Service de la bibliothèque Avertissement L’auteur de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse a autorisé l’Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières à diffuser, à des fins non lucratives, une copie de son mémoire ou de sa thèse. Cette diffusion n’entraîne pas une renonciation de la part de l’auteur à ses droits de propriété intellectuelle, incluant le droit d’auteur, sur ce mémoire ou cette thèse. Notamment, la reproduction ou la publication de la totalité ou d’une partie importante de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse requiert son autorisation. RÉSUMÉ L'objectif principal de cette recherche vise à mettre en lumière la transition culturelle qui s'effectue à Trois-Rivières au cours des années 1960. Le milieu culturel se transforme à plusieurs niveaux: les lieux de diffusion culturelle, les acteurs ainsi que la programmation culturelle en sont des exemples. L'analyse démontre tout le processus de démocratisation de la culture cultivée pris en charge par l'élite ainsi que l'émergence, à la fin de la décennie, de la démocratie culturelle mise de l'avant par une jeunesse qui sait s'imposer. Ces deux groupes ont su démontrer les caractéristiques dominantes de la diffusion de la culture cultivée dans une ville moyenne comme Trois-Rivières. -

White Paper on Francophone Arts and Culture in Ontario Arts and Culture

FRANCOPHONE ARTS AND CULTURE IN ONTARIO White Paper JUNE 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 05 BACKGROUND 06 STATE OF THE FIELD 09 STRATEGIC ISSUES AND PRIORITY 16 RECOMMANDATIONS CONCLUSION 35 ANNEXE 1: RECOMMANDATIONS 36 AND COURSES OF ACTION ARTS AND CULTURE SUMMARY Ontario’s Francophone arts and culture sector includes a significant number of artists and arts and culture organizations, working throughout the province. These stakeholders are active in a wide range of artistic disciplines, directly contribute to the province’s cultural development, allow Ontarians to take part in fulfilling artistic and cultural experiences, and work on the frontlines to ensure the vitality of Ontario’s Francophone communities. This network has considerably diversified and specialized itself over the years, so much so that it now makes up one of the most elaborate cultural ecosystems in all of French Canada. However, public funding supporting this sector has been stagnant for years, and the province’s cultural strategy barely takes Francophones into account. While certain artists and arts organizations have become ambassadors for Ontario throughout the country and the world, many others continue to work in the shadows under appalling conditions. Cultural development, especially, is currently the responsibility of no specific department or agency of the provincial government. This means that organizations and actors that increase the quality of life and contribute directly to the local economy have difficulty securing recognition or significant support from the province. This White Paper, drawn from ten regional consultations held throughout the province in the fall of 2016, examines the current state of Francophone arts and culture in Ontario, and identifies five key issues. -

AUTHOR Guindon, Rene; Poulin, Pierre Francophones in Canada: A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 441 FL 025 787 AUTHOR Guindon, Rene; Poulin, Pierre TITLE Francophones in Canada: A Community of Interests. New Canadian Perspectives . Les liens dans la francophonie canadienne. Nouvelles Perspectives Canadiennes. INSTITUTION Canadian Heritage, Ottawa (Ontario). ISBN ISBN-0-662-62279-0 ISSN ISSN-1203-8903 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 112p. AVAILABLE FROM Official Languages Support Programs, Department of Canadian Heritage, 15 Eddy, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A-0M5 (Cat. no. CH-2/1-1996); Tel: 819-994-2224; Web site: http://www.pch.gc.ca/offlangoff/perspectives/index.htm (free). PUB TYPE Books (010)-- Reports Descriptive (141)-- Multilingual/Bilingual Materials (171) LANGUAGE English, French EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Exchange; Demography; Economic Factors; Educational Mobility; Educational Policy; Faculty Mobility; Foreign Countries; *French; *French Canadians; Information Dissemination; *Intergroup Relations; Kinship; *Land Settlement; *Language Minorities; *Language Role; Mass Media; Migration Patterns; Shared Resources and Services; Social Networks; Social Support Groups; Tourism IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Francophone Education (Canada); Francophonie ABSTRACT This text examines the ties that bind Francophones across Canada to illustrate the diversity and depth of the Canadian Francophone community. Observations are organized into seven chapters. The first looks at the kinship ties of Canadian Francophones, including common ancestral origins, settlement of the Francophone regions, and existence of two particularly large French Canadian families, one in Acadia and one in Quebec. The second chapter outlines patterns of mobility in migration, tourism, and educational exchange. Chapter three looks at the circulation of information within and among Francophone communities through the mass media, both print and telecommunications. The status of cultural exchange (literary, musical, and theatrical) is considered next.