Tantra 1 Tantra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science Behind Sandhya Vandanam

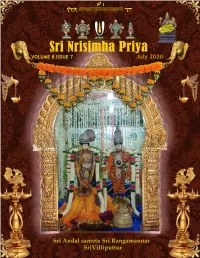

|| 1 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 Sri Vaidya Veeraraghavan – Nacchiyar Thirukkolam - Thiruevvul 2 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 �ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || Sri Nrisimha Priya ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ AN AU T H O R I S E D PU B L I C A T I O N OF SR I AH O B I L A M A T H A M H. H. 45th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham H.H. 46th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham Founder Sri Nrisimhapriya (E) H.H. Sri Lakshminrisimha H.H. Srivan Sathakopa Divya Paduka Sevaka Srivan Sathakopa Sri Ranganatha Yatindra Mahadesikan Sri Narayana Yatindra Mahadesikan Ahobile Garudasaila madhye The English edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya not only krpavasat kalpita sannidhanam / brings to its readers the wisdom of Vaishnavite Lakshmya samalingita vama bhagam tenets every month, but also serves as a link LakshmiNrsimham Saranam prapadye // between Sri Matham and its disciples. We confer Narayana yatindrasya krpaya'ngilaraginam / our benediction upon Sri Nrisimhapriya (English) Sukhabodhaya tattvanam patrikeyam prakasyate // for achieving a spectacular increase in readership SriNrsimhapriya hyesha pratigeham sada vaset / and for its readers to acquire spiritual wisdom Pathithranam ca lokanam karotu Nrharirhitam // and enlightenment. It would give us pleasure to see all devotees patronize this spiritual journal by The English Monthly Edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya is becoming subscribers. being published for the benefit of those who are better placed to understand the Vedantic truths through the medium of English. May this magazine have a glorious growth and shine in the homes of the countless devotees of Lord Sri Lakshmi Nrisimha! May the Lord shower His benign blessings on all those who read it! 3 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 4 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || CONTENTS Sri Nrisimha Priya Owner: Panchanga Sangraham 6 H.H. -

Kirtan Leelaarth Amrutdhaara

KIRTAN LEELAARTH AMRUTDHAARA INSPIRERS Param Pujya Dharma Dhurandhar 1008 Acharya Shree Koshalendraprasadji Maharaj Ahmedabad Diocese Aksharnivasi Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Hariswaroopdasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Dharmanandandasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) PUBLISHER Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple (Kenton-Harrow) (Affiliated to Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj – Kutch) PUBLISHED 4th May 2008 (Chaitra Vad 14, Samvat 2064) Produced by: Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton Harrow All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. © Copyright 2008 Artwork designed by: SKSS Temple I.T. Centre © Copyright 2008 Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton, Harrow Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple Westfield Lane, Kenton, Harrow Middlesex, HA3 9EA, UK Tel: 020 8909 9899 Fax: 020 8909 9897 www.sksst.org [email protected] Registered Charity Number: 271034 i ii Forword Jay Shree Swaminarayan, The Swaminarayan Sampraday (faith) is supported by its four pillars; Mandir (Temple), Shastra (Holy Books), Acharya (Guru) and Santos (Holy Saints & Devotees). The growth, strength and inter- supportiveness of these four pillars are key to spreading of the Swaminarayan Faith. Lord Shree Swaminarayan has acknowledged these pillars and laid down the key responsibilities for each of the pillars. He instructed his Nand-Santos to write Shastras which helped the devotees to perform devotion (Bhakti), acquire true knowledge (Gnan), practice righteous living (Dharma) and develop non- attachment to every thing material except Supreme God, Lord Shree Swaminarayan (Vairagya). There are nine types of bhakti, of which, Lord Shree Swaminarayan has singled out Kirtan Bhakti as one of the most important and fundamental in our devotion to God. -

Thirumangai Azhwar's Thirukkurunthandakam

Thirumangai AzhwAr’s ThirukkurunthANdakam Annotated Commentary in English By: Oppiliappan Koil SrI VaradAchAri SaThakopan sadagopan.org CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 Paasuram 1 6 Paasuram 2 8 Paasuram 3 10 Paasuram 4 & 5 11 Paasuram 6 13 Paasuram 7 & 8 14 Paasuram 9 & 10 15 Paasuram 11 & 12 16 Paasuram 13 & 14 18 Paasuram 15 & 16 19 Paasuram 17 & 18 21 Paasuram 19 22 Paasuram 20 23 sadagopan.org Nigamanam 24 sadagopan.org THIRUMANGAI AZHWAR VAIBHAVAM Parakalan at Ahobilam Thirumangai AzhwAr was the last of the Twelve AzhwArs. His Taniyan is: KaarthikE KrittikA Jaatham chathushkavi SikhAmaNim ShaDprabhandha kruthaM Saarnga-mUrthim kaliyamAsrayE sadagopan.org Thirumangai AzhwAr known as Kaliyan, ParakAlan was born in Nala samvathsaram, VriscchikA Maasam, PourNami dinam. It was a Thursday and KritthikA Nakshathram was in ascendance. His place of birth is Thirukkurayaloor near ThiruvAli-Thirunahari. His given name at birth was Neelan. He was born in Chathurtha VarNam and he mastered svakula Vidhyai of DhanussAsthram. With his mastery of archery and weapons handling, he was formidable in fights. He became a chieftain of a district in the kingdom of ChOLAs and served the ChOLA king. He had four ministers with the names of ThALUthuvAN, Neer-mEl NadappAn, Nizhalil MaRaivAn and ThOlA Vazhakkan. With their help and the carrying power of his horse with the name of AadalmA, Neelan was able to drive away many enemies of the ChOLA king and enjoyed an honoured status in the ChOLA Kingdom. Meanwhile, in a nearby village, there was a female child born as BhUmyamsai in an Aambal pond (Kumuda saras) and a Vaisyan took that child home and adopted it as his own. -

Decline in the Popularity of Sun Worship Chapter- Vi

CJI--IAPTER - V[ DECLINE IN THE POPULARITY OF SUN WORSHIP CHAPTER- VI DECLINE IN THE POPULARITY OF SUN WORSHIP The popularity of the Sun worship in Bengal down to the end of Hindu rule is indicated by the opening verse in the copperplates of Visvarupasena and Suryasena in praise of the Sun god. The extant remains of the icons of Surya, dated or undated, also suggest the continuity of Sun worship until at least the early mediaeval period. Perhaps. this popularity was partly the cause as well as effect of the deep-rooted belief recorded on the pedestal of a Surya image from BairhaHa (Dinajpur District) that the god was the healer of all diseases ('samasta-roganiim harllii l However, since the early part of the 13'h century A.D. things began to change in the disfavour of the Sun-cult. In actuality. the process started long back, specifically since the Sena Period. The northern style SGrya and his worship probably did not last long alter the Varman-Sena period: at least we hardly come across any such images aflerwards. There could be various reasons t(1r the subsequent decline in the importance and anthropomorphic worship of the Sun in early Bengal. However. it is also to be kept in mind that the solar worship in the t(ml1S stated alxl\e did not only disappear from this part of eastern India, but also from the rest of the Indian sub-continent. Naturally. the question rises as to what led to the decline of the solar-cult. No mysticism, symbolism or high philosophy around SOrya: The daily visibility of the Sun to naked eye prevented the sectarians to develop any mysticism, symbolism or high philosophy centering round him. -

Tantra and Hatha Yoga

1 Tantra and Hatha Yoga. A little history and some introductory thoughts: These areas of practice in yoga are really all part of the same, with Tantra being the historical development in practice that later spawned hatha yoga. Practices originating in these traditions form much of what we practice in the modern day yoga. Many terms, ideas and theories that we use come from this body of knowledge though we may not always fully realise it or understand or appreciate their original context and intent. There are a huge number of practices described that may or may not seem relevant to our current practice and interests. These practices are ultimately designed for complete transformation and liberation, but along the way there are many practices designed to be of therapeutic value to humans on many levels and without which the potential for transformation cannot happen. Historically, Tantra started to emerge around the 6th to 8th Centuries A.D. partly as a response to unrealistic austerities in yoga practice that some practitioners were espousing in relation to lifestyle, food, sex and normal householder life in general. Tantra is essentially a re-embracing of all aspects of life as being part of a yogic path; the argument being that if indeed all of life manifests from an underlying source and is therefore all interconnected then all of life is inherently spiritual or worthy of our attention. And indeed, if we do not attend to all aspects of life in our practice this can lead to problems and imbalances. This embracing of all of life includes looking at our shadows and dark sides and integrating or transforming them, ideas which also seem to be embraced in modern psychology. -

Bharatanatyam: Eroticism, Devotion, and a Return to Tradition

BHARATANATYAM: EROTICISM, DEVOTION, AND A RETURN TO TRADITION A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Religion In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Taylor Steine May/2016 Page 1! of 34! Abstract The classical Indian dance style of Bharatanatyam evolved out of the sadir dance of the devadāsīs. Through the colonial period, the dance style underwent major changes and continues to evolve today. This paper aims to examine the elements of eroticism and devotion within both the sadir dance style and the contemporary Bharatanatyam. The erotic is viewed as a religious path to devotion and salvation in the Hindu religion and I will analyze why this eroticism is seen as religious and what makes it so vital to understanding and connecting with the divine, especially through the embodied practices of religious dance. Introduction Bharatanatyam is an Indian dance style that evolved from the sadir dance of devadāsīs. Sadir has been popular since roughly the 6th century. The original sadir dance form most likely originated in the area of Tamil Nadu in southern India and was used in part for temple rituals. Because of this connection to the ancient sadir dance, Bharatanatyam has historic traditional value. It began as a dance style performed in temples as ritual devotion to the gods. This original form of the style performed by the devadāsīs was inherently religious, as devadāsīs were women employed by the temple specifically to perform religious texts for the deities and for devotees. Because some sadir pieces were dances based on poems about kings and not deities, secularism does have a place in the dance form. -

TANTRA RETREAT Online with Radha & Yogi Vishnu Panigrahi

TANTRA RETREAT online with Radha & Yogi Vishnu Panigrahi 12/13/14 june “Tantra says to accept whatever you are. This is the fundamental characteristic: total acceptance, and only through total acceptance will it be possible for you to grow. " Program: First day 9 pm entrance ceremony with Puja 930 1030 pm tantra philosophy with Vishnu 1045 12 pm tantra yoga practice with Radha Second day 1pm-230 pm tantra philosophy with Vishnu 245-430pm Tantra yoga with Radha Third day 1-230 pm tantra philosophy with Vishnu 245-430 pm hours Yoga tantra with Radha In this process you will be given Tantra yoga techniques, some of which come from the Kaula tradition. The student will learn some Nyasa practices (a means of consecrating the physical body by entering an elevated awareness or divine consciousness in various parts of the body during tantric rituals. This is widely described in Mahanirvana Tantra. The word "nyasa" therefore means " superimpression ”through conscious touch), some specific tantric sequences to transfigure, transcend and sublimate sexual energy, mudras and mantras that allow us to recognize this energy and celebrate it as a sacred essence, ancient practices of tantric Yoginis to recognize the female power present in each of us, sacred visualizations (yantra) to be performed before, in the meantime and after the act of union between the divine shiva (lingam) and the divine shakti (yoni). The course is open to all people who have a pure and high interest. The Philosophical study of tantra texts conducted by Vishnu will be of fundamental importance to enter the sacredness of physical practice and with great ability and dedication will lead you to truly understand the essence of Tantra in all its aspects. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Dasti Yoga © 2015 by Richard Merrill Dasti Yoga Is a Spiritual Practice of Devotion Through Craft and Art, As Well As Other Handwork

Dasti Yoga © 2015 by Richard Merrill Dasti Yoga is a spiritual practice of devotion through craft and art, as well as other handwork. The word dasti means “of the hand, or pertaining to the hand.”i It is associated with kriya yoga, or karma yoga, of which there are many variants. Lekh Raj Puriii defines Dasti Yoga as yoga “with the hands,” in such activities as the telling of rosary beads, as well as in the handcrafts and trades. Dasti yoga can involve any activity with the hands, from washing dishes to playing a violin sonata. It is the remembering of God while performing good and useful actions. Its relationship to karma yoga is in the performing of actions as worship, without any desire for benefit or rewardiii. Sri Swami Satchidananda quotes a Hindu saying, ‘ “Man me Ram, hath me kam.” “There is work in the hand, but Ram [God] in the mind.” iv This is the state of one who has realized the goal of Dasti yoga. One example of an ancient Dasti practice is Dasti Attam, or dasi attam, sacred temple dancing once performed as worship in southern India by devadasis, or “servants of God”v. Indira dasi, a classical dancer and authority on the history of the dance arts in India, writes in Classical Indian Temple Dancevi that the devas or demi-gods were sent to earth by their father to perform drama and dance in order to lift a curse that had been placed upon them. They founded the arts as they are known today. This is the mythic origin of the Indian classical dance form Bharatha Natyam, widely recognized as India’s national dance. -

Contents by Tradition Vii Contents by Country Ix Contributors Xi

CONTENTS Contents by Tradition vii Contents by Country ix Contributors xi Introduction • David Gordon White 1 Note for Instructors • David Gordon White 24 Foundational Yoga Texts 29 1. The Path to Liberation through Yogic Mindfulness in Early Āyurveda • Dominik Wujastyk 31 2. A Prescription for Yoga and Power in the Mahābhārata • James L. Fitzgerald 43 3. Yoga Practices in the Bhagavadgītā • Angelika Malinar 58 4. Pātañjala Yoga in Practice • Gerald James Larson 73 5. Yoga in the Yoga Upanisads: Disciplines of the Mystical OM Sound • Jeffrey Clark Ruff 97 6. The Sevenfold Yoga of the Yogavāsistha • Christopher Key Chapple 117 7. A Fourteenth-Century Persian Account of Breath Control and • Meditation Carl W. Ernst 133 Yoga in Jain, Buddhist, and Hindu Tantric Traditions 141 8. A Digambara Jain Description of the Yogic Path to • Deliverance Paul Dundas 143 • 9. Saraha’s Queen Dohās Roger R. Jackson 162 • 10. The Questions and Answers of Vajrasattva Jacob P. Dalton 185 11. The Six-Phased Yoga of the Abbreviated Wheel of Time Tantra n • (Laghukālacakratantra) according to Vajrapā i Vesna A. Wallace 204 12. Eroticism and Cosmic Transformation as Yoga: The Ātmatattva sn • of the Vai ava Sahajiyās of Bengal Glen Alexander Hayes 223 White.indb 5 8/18/2011 7:11:21 AM vi C O ntents m 13. TheT ransport of the Ha sas: A Śākta Rāsalīlā as Rājayoga in Eighteenth-Century Benares • Somadeva Vasudeva 242 Yoga of the Nāth Yogīs 255 14. The Original Goraksaśataka • James Mallinson 257 T 15. Nāth Yogīs, Akbar, and the “Bālnāth illā” • William R. Pinch 273 16. -

Tantra As Experimental Science in the Works of John Woodroffe

Julian Strube Tantra as Experimental Science in the Works of John Woodroffe Abstract: John Woodroffe (1865–1936) can be counted among the most influential authors on Indian religious traditions in the twentieth century. He is credited with almost single-handedly founding the academic study of Tantra, for which he served as a main reference well into the 1970s. Up to that point, it is practically impossible to divide his influence between esoteric and academic audiences – in fact, borders between them were almost non-existent. Woodroffe collaborated and exchangedthoughtswithscholarssuchasSylvainLévi,PaulMasson-Oursel,Moriz Winternitz, or Walter Evans-Wentz. His works exerted a significant influence on, among many others, Heinrich Zimmer, Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, Mircea Eliade, Carl Gustav Jung, Agehananda Bharati or Lilian Silburn, as they did on a wide range of esotericists such as Julius Evola. In this light, it is remarkable that Woodroffe did not only distance himself from missionary and orientalist approaches to Tantra, buthealsoidentifiedTantrawithCatholicism and occultism, introducing a univer- salist, traditionalist perspective. This was not simply a “Western” perspective, since Woodroffe echoed Bengali intellectuals who praised Tantra as the most appropriate and authen- tic religious tradition of India. In doing so, they stressed the rational, empiri- cal, scientific nature of Tantra that was allegedly based on practical spiritual experience. As Woodroffe would later do, they identified the practice of Tantra with New Thought, spiritualism, and occultism – sciences that were only re-discovering the ancient truths that had always formed an integral part of “Tantrik occultism.” This chapter situates this claim within the context of global debates about modernity and religion, demonstrating how scholarly approaches to religion did not only parallel, but were inherently intertwined with, occultist discourses. -

A History of Legal and Moral Regulation of Temple Dance in India

Naveiñ Reet: Nordic Journal of Law and Social Research (NNJLSR) No.6 2015, pp. 131-148 Dancing Through Laws: A History of Legal and Moral Regulation of Temple Dance in India Stine Simonsen Puri Introduction In 1947, in the state of Tamil Nadu in South India, an Act was passed, “The Tamil Nadu Devadasis (Prevention of Dedication) Act,” which among other things banned the dancing of women in front of Hindu temples. The Act was to target prostitution among the so-called devadasis that were working as performers within and beyond Hindu temples, and who, according to custom also were ritually married or dedicated to temple gods. The Act was the culmination of decades of public and legal debates centred on devadasis, who had come to symbolize what was considered a degenerated position of women within Hindu society. Concurrent with this debate, the dance of the devadasis which had developed through centuries was revived and reconfigured among the Indian upper class; and eventually declared one of Indian national dances, called bharatanatyam (which can translate as Indian dance). Today, while parts of the devadasi tradition have been banned, bharatanatyam is a popular activity for young girls and women among the urban middle and upper classes in all parts of India. The aim of this article is to examine moral boundaries tied to the female moving body in India. I do so by looking into the ways in which the regulation of a certain kind of dancers has framed the moral boundaries for contemporary young bharatanatyam dancers. A focus on legal and moral interventions in dance highlights the contested role of the female body in terms of gender roles, religious ideology, and moral economy.