Tantra As Experimental Science in the Works of John Woodroffe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress

THEOSOPHY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS By Mark Bevir Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley Berkeley CA 94720 USA [E-mail: [email protected]] ABSTRACT A study of the role of theosophy in the formation of the Indian National Congress enhances our understanding of the relationship between neo-Hinduism and political nationalism. Theosophy, and neo-Hinduism more generally, provided western-educated Hindus with a discourse within which to develop their political aspirations in a way that met western notions of legitimacy. It gave them confidence in themselves, experience of organisation, and clear intellectual commitments, and it brought them together with liberal Britons within an all-India framework. It provided the background against which A. O. Hume worked with younger nationalists to found the Congress. KEYWORDS: Blavatsky, Hinduism, A. O. Hume, India, nationalism, theosophy. 2 REFERENCES CITED Archives of the Theosophical Society, Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras. Banerjea, Surendranath. 1925. A Nation in the Making: Being the Reminiscences of Fifty Years of Public Life . London: H. Milford. Bharati, A. 1970. "The Hindu Renaissance and Its Apologetic Patterns". In Journal of Asian Studies 29: 267-88. Blavatsky, H.P. 1888. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy . 2 Vols. London: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1972. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology . 2 Vols. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1977. Collected Writings . 11 Vols. Ed. by Boris de Zirkoff. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. Campbell, B. 1980. Ancient Wisdom Revived: A History of the Theosophical Movement . Berkeley: University of California Press. -

Tantric Texts Series Edited by Arthur Avalon (John Woodroffe)

KAMAKALAVILASA First Published 1922 Second Edition 1953 Printed by D. V. Syamala Rau, at the Vasanta Press, The Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madias 20 SHRI YANTRA DESCRIPTION OF THE CAKE AS FROM THE CENTRE OUTWARD 1 . Red Point— Sarvfmandamaya. (vv. 22-24, 37, 38). 2. White triangle inverted— Sarvasiddhiprada. (vv. 25, iYi). 3. Eight red triangles -Sarvarogahara. (vv. 29, 40). 4. Ten blue triangles — Sarvaraksakara. (vv. 30, 41). 5. Ten red triangles —Sarvarthasadhaka. (vv. 30, 31, 42). 6. Fourteen blue triangles — Sarvasaubhagyadayaka. (vv. 31, 43). 7. Eight-petalled red lotus — Sarvasarhksobhana. (vv. 33, 41). .S. Sixteen-petalled blue lotus —Sarvasaparipuraka. (vv. 33, 45). 9. Yellow surround —Trailokyamohana. (vv. 34, 46-49). KAMAKALAVILASA BY PUNYANANDANATHA WITH THE COMMENTARY OF NATANANANDANATHA TRANSLATED WITH COMMENTARY BY ARTHUR AVALON WITH NATHA-NAVARATNAMALIKA WITH COMMENTARY MANjUSA Bv BHASKARARAYA 2nd Edition Revised and enlarged Publishers : GANE8H & Co., (MADRAS) Ltd., MADRAS— 17 1958 PUBLISHERS' NOTE The Orientalists' system of transliteration has been followed in this work. 3T a, 3T1 i, I, r, a, f f S u, 5 u, 3£ r, <5 1, c| J " ^ e, ^ ai, oft o, ^ au, m or rh, : h. f k, ^ kh, JTg, ^ gh, S n, Z t, $ th, S d, Z tfh, qT n, ^ t, ^ th, <? d, * dh, ^ n, *Tp, <Jiph, ^b, flbh, ^m, \ y, ^ r, 53 1, W v, ss * s, ^ s, ^ h, 55 1. PREFACE The KamakalA"vila*sa is an important work in S'rlvidya by Punya"nanda an adherent of the Hadimata, who is also the commentator on the Yoginihrdaya, a section called Uttara- catuhs'ati of the great Vamakes'vara Tantra. -

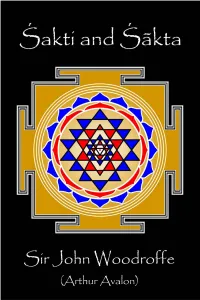

Essays and Addresses on the Śākta Tantra-Śāstra

ŚAKTI AND ŚĀKTA ESSAYS AND ADDRESSES ON THE ŚĀKTA TANTRAŚĀSTRA BY SIR JOHN WOODROFFE THIRD EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED Celephaïs Press Ulthar - Sarkomand - Inquanok – Leeds 2009 First published London: Luzac & co., 1918. Second edition, revised and englarged, London: Luzac and Madras: Ganesh & co., 1919. Third edition, further revised and enlarged, Ganesh / Luzac, 1929; many reprints. This electronic edition issued by Celephaïs Press, somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills, and mani(n)fested in the waking world in Leeds, England in the year 2009 of the common error. This work is in the public domain. Release 0.95—06.02.2009 May need furthur proof reading. Please report errors to [email protected] citing release number or revision date. PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION. HIS edition has been revised and corrected throughout, T and additions have been made to some of the original Chapters. Appendix I of the last edition has been made a new Chapter (VII) in the book, and the former Appendix II has now been attached to Chapter IV. The book has moreover been very considerably enlarged by the addition of eleven new Chapters. New also are the Appendices. The first contains two lectures given by me in French, in 1917, before the Societé Artistique et Literaire Francaise de Calcutta, of which Society Lady Woodroffe was one of the Founders and President. The second represents the sub- stance (published in the French Journal “Le Lotus bleu”) of two lectures I gave in Paris, in the year 1921, before the French Theosophical Society (October 5) and at the Musée Guimet (October 6) at the instance of L’Association Fran- caise des amis de L’Orient. -

Abhinavagupta's Theory of Relection a Study, Critical Edition And

Abhinavagupta’s Theory of Relection A Study, Critical Edition and Translation of the Pratibimbavāda (verses 1-65) in Chapter III of the Tantrāloka with the commentary of Jayaratha Mrinal Kaul A Thesis In the Department of Religion Presented in Partial Fulilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Religion) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada August 2016 © Mrinal Kaul, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Mrinal Kaul Entitled: Abhinavagupta’s Theory of Relection: A Study, Critical Edition and Translation of the Pratibimbavāda (verses 1-65) in Chapter III of the Tantrāloka with the commentary of Jayaratha and submitted in partial fulillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Religion) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the inal Examining Committee: _____________________________Chair Dr Christine Jourdan _____________________________External Examiner Dr Richard Mann _____________________________External to Programme Dr Stephen Yeager _____________________________Examiner Dr Francesco Sferra _____________________________Examiner Dr Leslie Orr _____________________________Supervisor Dr Shaman Hatley Approved by ____________________________________________________________ Dr Carly Daniel-Hughes, Graduate Program Director September 16, 2016 ____________________________________________ Dr André Roy, Dean Faculty of Arts and Science ABSTRACT Abhinavagupta’s Theory of Relection: A Study, Critical Edition and Translation of the Pratibimbavāda (verses 1-65) in the Chapter III of the Tantrāloka along with the commentary of Jayaratha Mrinal Kaul, Ph.D. Religion Concordia University, 2016 The present thesis studies the theory of relection (pratibimbavāda) as discussed by Abhinavagupta (l.c. 975-1025 CE), the non-dualist Trika Śaiva thinker of Kashmir, primarily focusing on what is often referred to as his magnum opus: the Tantrāloka. -

The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen

The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen To cite this version: Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen. The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and philological papers on a Vedic tradition. Arlo Griffiths; Annette Schmiedchen. 11, Shaker, 2007, Indologica Halensis, 978-3-8322-6255-6. halshs-01929253 HAL Id: halshs-01929253 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01929253 Submitted on 5 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Griffiths, Arlo, and Annette Schmiedchen, eds. 2007. The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and Philological Papers on a Vedic Tradition. Indologica Halensis 11. Aachen: Shaker. Contents Arlo Griffiths Prefatory Remarks . III Philipp Kubisch The Metrical and Prosodical Structures of Books I–VII of the Vulgate Atharvavedasam. hita¯ .....................................................1 Alexander Lubotsky PS 8.15. Offense against a Brahmin . 23 Werner Knobl Zwei Studien zum Wortschatz der Paippalada-Sam¯ . hita¯ ..................35 Yasuhiro Tsuchiyama On the meaning of the word r¯as..tr´a: PS 10.4 . 71 Timothy Lubin The N¯ılarudropanis.ad and the Paippal¯adasam. hit¯a: A Critical Edition with Trans- lation of the Upanis.ad and Nar¯ ayan¯ . a’s D¯ıpik¯a ............................81 Arlo Griffiths The Ancillary Literature of the Paippalada¯ School: A Preliminary Survey with an Edition of the Caran. -

Contents by Tradition Vii Contents by Country Ix Contributors Xi

CONTENTS Contents by Tradition vii Contents by Country ix Contributors xi Introduction • David Gordon White 1 Note for Instructors • David Gordon White 24 Foundational Yoga Texts 29 1. The Path to Liberation through Yogic Mindfulness in Early Āyurveda • Dominik Wujastyk 31 2. A Prescription for Yoga and Power in the Mahābhārata • James L. Fitzgerald 43 3. Yoga Practices in the Bhagavadgītā • Angelika Malinar 58 4. Pātañjala Yoga in Practice • Gerald James Larson 73 5. Yoga in the Yoga Upanisads: Disciplines of the Mystical OM Sound • Jeffrey Clark Ruff 97 6. The Sevenfold Yoga of the Yogavāsistha • Christopher Key Chapple 117 7. A Fourteenth-Century Persian Account of Breath Control and • Meditation Carl W. Ernst 133 Yoga in Jain, Buddhist, and Hindu Tantric Traditions 141 8. A Digambara Jain Description of the Yogic Path to • Deliverance Paul Dundas 143 • 9. Saraha’s Queen Dohās Roger R. Jackson 162 • 10. The Questions and Answers of Vajrasattva Jacob P. Dalton 185 11. The Six-Phased Yoga of the Abbreviated Wheel of Time Tantra n • (Laghukālacakratantra) according to Vajrapā i Vesna A. Wallace 204 12. Eroticism and Cosmic Transformation as Yoga: The Ātmatattva sn • of the Vai ava Sahajiyās of Bengal Glen Alexander Hayes 223 White.indb 5 8/18/2011 7:11:21 AM vi C O ntents m 13. TheT ransport of the Ha sas: A Śākta Rāsalīlā as Rājayoga in Eighteenth-Century Benares • Somadeva Vasudeva 242 Yoga of the Nāth Yogīs 255 14. The Original Goraksaśataka • James Mallinson 257 T 15. Nāth Yogīs, Akbar, and the “Bālnāth illā” • William R. Pinch 273 16. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

The Malleability of Yoga: a Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 25 Article 4 November 2012 The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Jain, Andrea R. (2012) "The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 25, Article 4. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1510 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Jain: The Malleability of Yoga The Malleability of Yoga: A Response to Christian and Hindu Opponents of the Popularization of Yoga Andrea R. Jain Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis FOR over three thousand years, people have yoga is Hindu. This assumption reflects an attached divergent meanings and functions to understanding of yoga as a homogenous system yoga. Its history has been characterized by that remains unchanged by its shifting spatial moments of continuity, but also by divergence and temporal contexts. It also depends on and change. This applies as much to pre- notions of Hindu authenticity, origins, and colonial yoga systems as to modern ones. All of even ownership. Both Hindu and Christian this evidences yoga’s malleability (literally, the opponents add that the majority of capacity to be bent into new shapes without contemporary yogis fail to recognize that yoga breaking) in the hands of human beings.1 is Hindu.3 Yet, today, a movement that assumes a Suspicious of decontextualized vision of yoga as a static, homogenous system understandings of yoga and, consequently, the rapidly gains momentum. -

The Amṛtasiddhi: Haṭhayoga'stantric Buddhist

chapter 17 The Amṛtasiddhi: Haṭhayoga’s Tantric Buddhist Source Text James Mallinson Like many of the contributors to this volume, I had the great fortune to have Professor Sanderson as the supervisor of my doctoral thesis, which was a critical edition of an early text on haṭhayoga called the Khecarīvidyā. At the outset of my work on the text, and for several subsequent years, I expected that Sander- son’s encyclopedic knowledge of the Śaiva corpus would enable us to find within it forerunners of khecarīmudrā, the haṭhayogic practice central to the Khecarīvidyā. However, notwithstanding a handful of instances of teachings on similar techniques, the fully-fledged practice does not appear to be taught in earlier Śaiva works. In subsequent years, as I read more broadly in the corpus of early texts on haṭhayoga (which, in comparison to the vast Śaiva corpus, is relatively small and thus may easily be read by one individual), I came to the realisation that almost all of the practices which distinguish haṭhayoga from other methods of yoga were unique to it at the time of their codification and are not to be found in the corpus of earlier Śaiva texts, despite repeated asser- tions in secondary literature that haṭhayoga was a development from Śaivism (or “tantra” more broadly conceived). The texts of the haṭhayoga corpus do, however, couch their teachings in tantric language. The name of the haṭhayogic khecarīmudrā, for example, is also that of an earlier but different Śaiva practice. When I was invited to speak at the symposium in Professor -

Tantric Texts Series Edited by Arthur Avalon (John Woodroffe)

HYMN TO KALI KARPURADI-STOTRA Second Edition 1953 Printed by D. V. Syamala Rau, at the Vasanta Press. The Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras 20 HYMN TO KALI KARPURADI-STOTRA BY ARTHUR AVALON WITH INTRODUCTION AND COMMENTARY By VIMALSNANDA-S'VSMI 2nd Edition Revised and enlarged PUBLISHEES : GANESH & Co., (MADRAS) Ltd., MADRAS— 17 1958 PUBLISHERS* NOTE The Orientalists' system of transliteration has been followed in this work. sr a, «n a, i, i, 3 u, l, * f 5 n, *j r, 5£ f, ^ ^ i ~ ^ e, ^ ai, aft o, ®ft au, m or rh, : h. %k, ^ kh, *{ g, ^ gh, * n, *% c, ^ ch, ^ j, ^ jh, *[ fi, ^ t, $ th, f d, S dh, or n, ^ t, ^ th, ^ d, ^ dh, ^ n, ^p, <J>ph, ^b, <Tbh, ^m, \ y, \ r, 3 1, ^ v, ^ s', ^ s, ^ s, ^ h, 55 I. CONTENTS PAGE . 1-42 Preface .... Hymn to Kali ..... 43-96 . • • • U\ 5Hf^TO%Tf^cP'R .... «*KI«ri\u| SjqtiR5«H^ .... n«raWrarsRWR .... m-m VI PAGE #5Rqi^f <KS$fclWP^ .... \\\ Appendix I ^?T*TflTfa5|iT and g^tf^t . ii sWrgapr: . \M in ?iSTft?fe: . v sqn?qi%Ticram>w^qT5nH35fiq: . JM-tv — By the same Author SHAKTI AND SHAKTA Essays and Addresses on the Shakta Tantra Shastra CONTENTS Section 1.—Introductory—Chapters I—XIII Bharata Dharma—The World as Power (Shakti)—The Tantras—Tantra and Veda Shastras—The Tantras and Religion of the Shaktas— Shakti and Shakta—Is Shakti Force ? —Chlnachara—Tantra Shastras in China—A Tibetan Tantra— Shakti in Taoism—Alleged Conflict of Shastras Sarvanandanatha. Section 2.—Doctrinal—Chapters XIV—XX Chit Shakti—Maya Shakti—Matter and Consciousness Shakti and Maya—Shakta Advaitavada—Creation—The Indian Magna Mater. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature. -

The Texts of Alice A. Bailey: an Inquiry Into the Role of Esotericism in Transforming Consciousness

THE TEXTS OF ALICE A. BAILEY: AN INQUIRY INTO THE ROLE OF ESOTERICISM IN TRANSFORMING CONSCIOUSNESS I Wightman Doctor of Philosophy 2006 University of Western Sydney. IN APPRECIATION This thesis would not have been possible without the care, support, enthusiasm and intellectual guidance of my supervisor, Dr Lesley Kuhn, who has followed my research journey with dedicated interest throughout. I also acknowledge the loving kindness of Viveen at Sydney Goodwill, who has continuously praised and encouraged my work, and provided me with background material on the kind of activities that the worldwide community of Alice A. Bailey students are involved in. I sincerely appreciate the role my husband, Greg, played, as my cosmic co-traveller. Without him this thesis would never have materialized, his tireless engagement throughout these years has bolstered my drive to proceed to the very end. Finally, I acknowledge my children, Victoria and Elizabeth, for tolerating my reclusive behaviour, and giving me the space I have needed to write. Philosophy, in one of its functions, is the critic of cosmologies. It is its function to harmonise, refashion, and justify divergent intuitions as to the nature of things. It has to insist on the scrutiny of ultimate ideas, and on the retention of the whole of the evidence in shaping our cosmological scheme. Its business is to render explicit, and –so far as may be – efficient, a process which otherwise is unconsciously performed without rational tests (Alfred North Whitehead 1938:7). TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Letter Code for the Bailey Texts v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Researching the work of Alice A.