No Brainer: the Early Modern Tragedy of Torture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intersecting Discourses of Renaissance Torture

Marshall Studies by Undergraduate Researchers at Guelph Vol. 1, No. 1, Fall 2007, 15-21 The body and truth: Intersecting discourses of Renaissance torture Laura Marshall This essay was prepared for ENGL*4040 Medieval and Early Modern Literature under the supervision of Prof. Alan Shepard, School of English and Theatre Studies, College of Arts. From the 13th to the 17th century torture became a component of the judicial system, the goal of which was to discover the veracity of the accused. Two primary, competing discourses developed in order to explain the epistemological value of torture, the dicens veritatis and the dicens dubitatis . In the first discourse, torture exists as a producer of legitimate truth, while in the second the use of torture necessarily casts doubt on the obtained confession. This essay examines the ways in which the victim can undermine the torture process through the manipulation of these discourses. This is done within the dicens veritatis when the victim claims innocence and forces the torturer to accept this as truth. Within the dicens dubitatis , this is accomplished by forcing torturers to acknowledge the flawed nature of their own discourse through the telling of lies. The first component of my examination explores the transcripts of the legal proceedings against Domenico Scandella and Jean Bourdil, identifying the differing ways these victims employ both discourses to create a resistance to the torturer’s predetermined narrative of events. The second component scrutinizes the depiction of the body within the philosophical writings of contemporary periods, thereby establishing the epistemological relationship between the body and pain. -

The Word They Still Shall Let Remain

The Word they still shall let remain: A Reformation pop-up exhibit This exhibit marks the 500th anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. We invite you to explore different perspectives on the Reformation, including the impact of print in producing the German, Swiss, radical, and English reform movements, as well as the response from the Catholic Church and the political ramifications of reform. Indulgences granted by several Popes of Rome in the several churches of Rome collected by William Crashaw in Fiscus Papalis, 1621. V.a.510(8), fol. 1-2v In 1095, Pope Urban II first introduced indulgences as pardons for sin to entice fighters to join the crusades. Later, these ephemeral sheets of forgiveness were granted for completed pilgrimages, for purchase to release souls from purgatory (the doctrine itself authorized in 1439), and were sold to cover sins during life out of the “Treasury of Merits,” a spiritual coffer that contained redemption through the deaths of martyrs and Christ. Rome officially announced the sale of indulgences in exchange for pardon of sin in 1476, 41 years before the 95 Theses. Pope Leo X provided the bishopric of Mainz to Albrecht of Brandenburg and then allowed him to sell indulgences to pay back personal debts. Indulgences are granted to this day for receiving Holy Communion, reciting the rosary, the exercise of the Stations of the Cross and reading scripture, among other acts. Here we see a manuscript account of the various indulgences offered and received, copied from Crashaw’s Fiscus Papalis and provides information on the amount of time remitted from purgatory. -

Preface Introduction

Notes Preface 1. Strong, “Popular Celebration,” 88. 2. Abrams, Historical Sociology, p. 192. Introduction 1. Raine, Depositions From the Courts of Durham, p. 160. 2. SP 15/15, no. 29(i). 3. Norton, “A Warning Against the Dangerous Practises of Papists,” sig. A5v; Strype, Annals, I, ii, p. 323; SP 15/17, nos. 72 and 73. 4. DUL DDR/EJ.CCD/1/2, f. 195;DDCL Raine MS. 124, ff. 180–82d. Most of the relevant Durham material is included in Raine, Depositions From the Courts of Durham. 5. CPR Elizabeth I, vol. VI, no. 1230. 6. Corporation of London Record Office, Repertories of the Court of Aldermen, vol. 16, fol. 520d. 7. Reid, “Rebellion of the Earls,” 171–203; MacCaffrey, Elizabethan Regime, p. 337; Wood, Riot, Rebellion and Popular Politics, pp. 72–3. Diarmaid MacCulloch and Anthony Fletcher differ somewhat in allowing that bastard feudal tenant loyalty had to be reinforced by “religious propaganda” to gather forces, but offer an explanation that remains focused on the lords and politics: The earls rebelled because denied the place in central affairs they thought rightfully theirs, and the significance of their failed efforts lie primarily in proving “that northern feudalism and particularism could no longer rival Tudor centralization”: Tudor Rebellions, pp. 102–16. 8. James, “Concept of Order,” 83. See also Meikle, “Godly Rogue,” 139. Meikle notes that Lord Hunsdon’s oft-quoted statement that the north “knew no prince but a Percy” should not be taken as accurate but rather as a “desperate plea for more military aid at the height of the rebellion.” 9. -

1 UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS 2 3 for the SECOND CIRCUIT 4 5 August Term, 2008 6 7 8 (In Banc Rehearing: December 9, 2008 Decided: November 2, 2009) 9 10 Docket No

06-4216-cv Arar v. Ashcroft 1 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS 2 3 FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT 4 5 August Term, 2008 6 7 8 (In Banc Rehearing: December 9, 2008 Decided: November 2, 2009) 9 10 Docket No. 06-4216-cv 11 12 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x 13 14 MAHER ARAR, 15 16 Plaintiff-Appellant, 17 18 - v.- 19 20 JOHN ASHCROFT, Attorney General of the 21 United States, LARRY D. THOMPSON, 22 formerly Acting Deputy Attorney General, 23 TOM RIDGE, Secretary of Homeland Security, 24 J. SCOTT BLACKMAN, formerly Regional 25 Director of the Regional Office of 26 Immigration and Naturalization Services, 27 PAULA CORRIGAN, Regional Director of 28 Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 29 EDWARD J. MCELROY, formerly District 30 Director of Immigration and Naturalization 31 Services for New York District, and now 32 Customs Enforcement, ROBERT MUELLER, 33 Director of the Federal Bureau of 34 Investigation, John Doe 1-10, Federal 35 Bureau of Investigation and/or Immigration 36 and Naturalization Service Agents, and JAMES 37 W. ZIGLAR, formerly Commissioner for 38 Immigration and Naturalization Services, 39 United States, 40 41 Defendants-Appellees. 42 43 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x 1Before: JACOBS, Chief Judge, McLAUGHLIN,** CALABRESI, * 2 CABRANES, POOLER, SACK,** SOTOMAYOR,*** PARKER,** 3 RAGGI, WESLEY, HALL, and LIVINGSTON, Circuit 4 Judges. KATZMANN, Circuit Judge, took no part in 5 the consideration or decision of the case. 6 7 JACOBS, C.J., filed the majority opinion in which MCLAUGHLIN, 8 CABRANES, RAGGI, WESLEY, HALL, and LIVINGSTON, JJ., joined. 9 10 CALABRESI, J., filed a dissenting opinion in which POOLER, SACK, 11 and PARKER, JJ., joined. -

Protestant Polemic in the 1570S: Elizabethan Responses to the Northern Rising, the Papal Bull and the Massacre of St Bartholomew‟S Day

Protestant Polemic in the 1570s: Elizabethan responses to the Northern Rising, the Papal Bull and the Massacre of St Bartholomew‟s Day by Mark Frederick Wilson A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures The University of Birmingham August 2013 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Between 1569 and 1572, a series of events, domestic and continental, occurred that shook the confidence of many Elizabethans, including those who served the Privy Council and Parliament. The Northern Rising (1569), the issue of Pius V‟s Papal Bull (1570) and the St Bartholomew‟s Day Massacre (1572), in Paris, all triggered political and polemical responses from those connected with the political institutions outlined above. The Protestant polemical print I have investigated, issued warnings to Elizabethans, via the perceived threats of foreign invasions, the fear of Papal power, sedition, treason, moral evils -

Torture Flights : North Carolina’S Role in the Cia Rendition and Torture Program the Commission the Commission

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 LIST OF COMMISSIONERS 4 FOREWORD Alberto Mora, Former General Counsel, Department of the Navy 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A Summary of the investigation into North Carolina’s involvement in torture and rendition by the North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torture (NCCIT) 8 FINDINGS 12 RECOMMENDATIONS CHAPTER ONE 14 CHAPTER SIX 39 The U.S. Government’s Rendition, Detention, Ongoing Challenges for Survivors and Interrogation (RDI) Program CHAPTER SEVEN 44 CHAPTER TWO 21 Costs and Consequences of the North Carolina’s Role in Torture: CIA’s Torture and Rendition Program Hosting Aero Contractors, Ltd. CHAPTER EIGHT 50 CHAPTER THREE 26 North Carolina Public Opposition to Other North Carolina Connections the RDI Program, and Officials’ Responses to Post-9/11 U.S. Torture CHAPTER NINE 57 CHAPTER FOUR 28 North Carolina’s Obligations under Who Were Those Rendered Domestic and International Law, the Basis by Aero Contractors? for Federal and State Investigation, and the Need for Accountability CHAPTER FIVE 34 Rendition as Torture CONCLUSION 64 ENDNOTES 66 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 78 APPENDICES 80 1 WWW.NCTORTUREREPORT.ORG TORTURE FLIGHTS : NORTH CAROLINA’S ROLE IN THE CIA RENDITION AND TORTURE PROGRAM THE COMMISSION THE COMMISSION THE COMMISSION THE COMMISSION FRANK GOLDSMITH (CO-CHAIR) JAMES E. COLEMAN, JR. PATRICIA MCGAFFAGAN DR. ANNIE SPARROW MBBS, MRCP, FRACP, MPH, MD Frank Goldsmith is a mediator, arbitrator and former civil James E. Coleman, Jr. is the John S. Bradway Professor Patricia McGaffagan worked as a psychologist for twenty rights lawyer in the Asheville, NC area. Goldsmith has of the Practice of Law, Director of the Center for five years at the Johnston County, NC Mental Health Dr. -

Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Blakeley, Ruth and Raphael, Sam (2013) Dirty Little Secrets: State and Corporate Complicity in Rendition, Secret Detention and Torture. In: British International Studies Association Annual Conference, June 2013, Birmingham. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/44066/ Document Version Pre-print Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Dirty Little Secrets Mapping State and Corporate Complicity in the Global Rendition System The Case of the UK Ruth Blakeley, University of Kent Sam Raphael, Kingston University Paper presented at the British International Studies Association Annual Conference Birmingham, 20 June 2013 Draft: Please seek permission from the authors before citing or circulating Abstract Based on a comprehensive investigation into the nature and evolution of the global rendition system, this paper seeks to provide an account of the extent of British involvement in and knowledge of that system. -

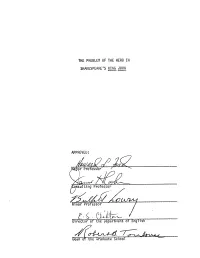

THE PROBLEM of the HERO in SHAKESPEARE's KING JOHN APPROVED: R Professor Suiting Professor Minor Professor Partment of English

THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN APPROVED: r Professor / suiting Professor Minor Professor l-Q [Ifrector of partment of English Dean or the Graduate School THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Wilbert Harold Ratledge, Jr., B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1970 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE MILIEU OF KING JOHN 7 III. TUDOR HISTORIOGRAPHY 12 IV. THE ENGLISH CHRONICLE PLAY 22 V. THE SOURCES OF KING JOHN 39 VI. JOHN AS HERO 54 VII. FAULCONBRIDGE AS HERO 67 VIII. ENGLAND AS HERO 82 IX. WHO IS THE VILLAIN? 102 X. CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY 118 in CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION During the last twenty-five years Shakespeare scholars have puolished at least five major works which deal extensively with Shakespeare's history plays. In addition, many critical articles concerning various aspects of the histories have been published. Some of this new material reinforces traditional interpretations of the history plays; some offers new avenues of approach and differs radically in its consideration of various elements in these dramas. King John is probably the most controversial of Shakespeare's history plays. Indeed, almost everything touching the play is in dis- pute. Anyone attempting to investigate this drama must be wary of losing his way among the labyrinths of critical argument. Critical opinion is amazingly divided even over the worth of King John. Hardin Craig calls it "a great historical play,"^ and John Masefield finds it to be "a truly noble play . -

April 21, 1967 Shock Opportunism and the Greek Junta

Yannick Verberckmoes 00903164 Master Program in American Studies Academic year: 2013-2014 April 21, 1967 Shock Opportunism and the Greek Junta Supervisor: Prof. Dr. J. Ken Kennard In this thesis we will investigate the concept of shock opportunism relating to the Greek colonels’ regime, that governed Greece from 1967 to 1974. Shock opportunism is defined as the use of a possibly premeditated collective shock, e.g. a natural disaster, war or coup d’état, as an opportunity to radically implement neoliberal economic reforms. On the one hand we will look at why and how this was done and on the other, we will link the case of Greece to similar examples of authoritarian regimes during the Cold War to come to a better analysis of this dark period in Greek history. Although writing a thesis is a very solitary endeavor, its merits can never be accredited to just one person. I would therefore like to express my gratitude to the following people: Prof. Dr. J. Ken Kennard: for yelling at me for about thirty minutes one week after the Easter break and explaining to me in quite straightforward English that my first draft still needed a lot of work, as this was a testimony to the great care and effort he displayed in helping me throughout the research and writing process. Prof. Dr. Victor Gavin: for his useful advice. Gizem Özbeko ğlu: for her undying support and access to the library of Boğaziçi University (Istanbul). Both of which were absolutely essential to the completion of this dissertation. Jannik Held: for introducing me to Naomi Klein’s book The Shock Doctrine over a couple of beers. -

Taking Psychological Torture Seriously

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2019 Taking Psychological Torture Seriously: The Torturous Nature of Credible Death Threats and the Collateral Consequences for Capital Punishment John Bessler University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation John Bessler, Taking Psychological Torture Seriously: The Torturous Nature of Credible Death Threats and the Collateral Consequences for Capital Punishment, 11 Northeastern University Law Review 1 (2019). Available at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/1080 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL. 11, NO. 1 NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 1 Taking Psychological Torture Seriously: The Torturous Nature of Credible Death Threats and the Collateral Consequences for Capital Punishment By John D. Bessler* * Associate Professor, University of Baltimore School of Law; Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University Law Center; Visiting Scholar/Research Fellow, Human Rights Center, University of Minnesota Law School (Spring 2018); Of Counsel, Berens & Miller, P.A., Minneapolis, Minnesota. 2 Bessler Table of Contents I. Introduction ...................................................................................3 II. The Illegality and Torturous Nature of Threats of Death ....... 14 A. Existing Legal Protections Against Death Threats Against Individuals.................................................................................... 14 B. Death Threats, Persecution, and the U.S. -

Tortured Testimonies

ACTA HISTRIAE • 19 • 2011 • 3 received: 2010-02-14 UDC 343.102:930.2"15/16" original scientific article TORTURED TESTIMONIES John JEFFRIES MARTIN Duke University, History Department, 114 Campus Drive, Box 90719, NC 27708 Durham, USA e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Manuals of jurisprudence in early modern Europe stipulated that the notary rec- ord not only the words but also the grimaces and the screams of the defendant during interrogations under torture. This paper explores these "tortured testimonies" from the Roman Inquisition, problematizes them as historical sources, and offers sugges- tions about how historians might approach them. The article examines the documents under two lights: (1) in relation to the institutional structures and protocols which gave them their particular form; and (2) in relation to the cultural assumptions that shaped a ritual in which pain was seen as an index of the conscience of the accused. Key words: inquisition, torture, testimony, notary, pain, trauma TORTURA E DEPOSIZIONI SINTESI I manuali di giurisprudenza risalenti agli inizi dell'Europa moderna stabilivano che il notaio registrasse non solo le parole ma anche le espressioni facciali e le grida dell'accusato durante gli interrogatori sotto tortura. L'articolo esplora alcune deposizioni sotto tortura presso l'Inquisizione romana, problematizzandole come fonti storiche e proponendo suggerimenti sulle modalità di accostamento a esse da parte degli storici. L'articolo esamina i documenti sotto due ottiche, vale a dire: (1) in relazione alle strutture istituzionali e ai protocolli che stanno alla base della loro forma peculiare; (2) in relazione alle assunzioni culturali che davano forma a un rituale in cui il dolore era visto come indice della coscienza dell'accusato. -

The Pit and the Pendulum Story Quest

The pit and the pendulum story quest Continue Introduction: Edgar Allan Poe Yam and pendulum set against the backdrop of the Spanish Inquisition. Throughout this WebQuest, you will become familiar with the Inquisition and why Po used it as the subject of his terrible story. Title Replies Views Last post Welcome to Dark Tales: Edgar Allan Poe's Pit and Pendulum Collector's Edition Forum 1,787 Please follow any TECH ISSUES for dark fairy tales: Edgar Allan Poe's Pit and Pendulum CE here. 20 3,057 Please answer your REVIEWS for dark fairy tales: Edgar Allan Poe in the pit and the CE pendulum here. 15 1,627 Dark Tales Series List 2 562 Bonus Games 3,935 Bonus Games Help Please 5 1178 Skull at the bottom of the cave 0 277 Runtime Bug 1 373 It needs an antibotic 1,489 This is where I go 0 414 Achievements 0 482 Skull in the Cave Bottom 0 0 0 314 2 achievements left (except gramophone) 5 1026 Piano Music 0 452 Skull Game 1,454 Bonus Game 4 630 bonus game 1,558 Can't break a bottle in the basement 1 416 Dark Tales: Edgar Allan Poe's Pit and Pendulum Collector's Edition 1,828 Can't Play 3,638 KEY: Unread Sticky Locked Ad Moved Moderator In preparation for lesson, review of online version of Pit and pendulum story by Edgar Allan Poe Yam and Pendulum Text Check Visual Poe More Visuals As you look at visual effects playing in the background to set the scene.