Title of Thesis Or Dissertation, Worded Exactly As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

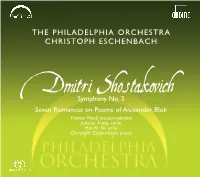

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

Marx, Bakunin, and the Question of Authoritarianism - David Adam

Marx, Bakunin, and the question of authoritarianism - David Adam Historically, Bakunin’s criticism of Marx’s “authoritarian” aims has tended to overshadow Marx’s critique of Bakunin’s “authoritarian” aims. This is in large part due to the fact that mainstream anarchism and Marxism have been polarized over a myth—that of Marx’s authoritarian statism—which they both share. Thus, the conflict in the First International is directly identified with a disagreement over anti-authoritarian principles, and Marx’s hostility toward Bakunin is said to stem from his rejection of these principles, his vanguardism, etc. Anarchism, not without justification, posits itself as the “libertarian” alternative to the “authoritarianism” of mainstream Marxism. Because of this, nothing could be easier than to see the famous conflict between the pioneering theorists of these movements—Bakunin and Marx—as a conflict between absolute liberty and authoritarianism. This essay will bring this narrative into question. It will not do this by making grand pronouncements about Anarchism and Marxism in the abstract, but simply by assembling some often neglected evidence. Bakunin’s ideas about revolutionary organization lie at the heart of this investigation. Political Philosophy We will begin by looking at some differences in political philosophy between Marx and Bakunin that will inform our understanding of their organizational disputes. In Bakunin, Marx criticized first and foremost what he saw as a modernized version of Proudhon’s doctrinaire attitude towards politics—the -

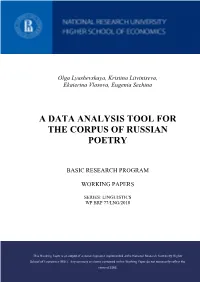

A Data Analysis Tool for the Corpus of Russian Poetry

Olga Lyashevskaya, Kristina Litvintseva, Ekaterina Vlasova, Eugenia Sechina A DATA ANALYSIS TOOL FOR THE CORPUS OF RUSSIAN POETRY BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: LINGUISTICS WP BRP 77/LNG/2018 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE. SERIES: LINGUISTICS Olga Lyashevskaya1, Kristina Litvintseva2, Ekaterina Vlasova3, Eugenia Sechina4 A Data Analysis Tool for the Corpus of Russian Poetry5 A data analysis tool of the Corpus of Russian Poetry (a part of the Russian National Corpus) is designed for quantitative research in various areas of versology and linguistics aspects of the poetic texts. The core part, a frequency database of the corpus, includes annotation at the level of texts, verses, words as well as patterns of words, letters, and stress. The tool allows a user to study certain properties (e. g. rhyming patterns, lexical co-occurrence) taken alone and in their interaction, both in the whole corpus and in subcorpora. Besides that, it facilitates the contrastive studies of two chosen subcorpora. The paper reports a few case studies demonstrating applicable descriptive and exploratory methods and potential for further research in the field of the digital literary studies. JEL Classification: Z. Keywords: poetic corpora, quantitative linguistics, lexical markers, lexical diversity, rhyme, linguistic poetics, versology, Russian language, Russian National Corpus 1. Introduction Russian versology has always heavily relied on statistics data as the basis for predictions and generalizations on meter, rhyme, and other formal and linguistic features of poetic language (see Gasparov 2005, Taranovsky 2010, Jakobson et al. -

Albert Camus' Dialogue with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky Sean Derek Illing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Between nihilism and transcendence : Albert Camus' dialogue with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky Sean Derek Illing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Illing, Sean Derek, "Between nihilism and transcendence : Albert Camus' dialogue with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1393. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1393 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BETWEEN NIHILISM AND TRANSCENDENCE: ALBERT CAMUS’ DIALOGUE WITH NIETZSCHE AND DOSTOEVSKY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Sean D. Illing B.A., Louisiana State University, 2007 M.A., University of West Florida, 2009 May 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the product of many supportive individuals. I am especially grateful for Dr. Cecil Eubank’s guidance. As a teacher, one can do no better than Professor Eubanks. Although his Socratic glare can be terrifying, there is always love and wisdom in his instruction. It is no exaggeration to say that this work would not exist without his support. At every step, he helped me along as I struggled to articulate my thoughts. -

Russian Poets and the October Revolution: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin and Others

Sylaiev, O., Razumenko, I., Tararak, O., Vorozhbit-Horbatiuk, V., Prokopchuk, I. / Volume 9 - Issue 27: 436-444 / March, 2020 436 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.34069/AI/2020.27.03.48 Russian Poets and the October Revolution: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin and Others Русские поэты и Октябрьская революция: Александр Блок, Сергей Есенин, Михаил Кузьмин и другие Poetas rusos y la revolución de octubre: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin y otros Received: January 22, 2020 Accepted: March 21, 2020 Written by: Oleksandr Sylaiev151 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-2388-5951 Iryna Razumenko152 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-3221-4340 Oleksandr Tararak153 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-9740-0750 Viktoriia Vorozhbit-Horbatiuk154 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5138-9226 Inna Prokopchuk155 ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9353-2169 Abstract Аннотация The article considers the question of the В статье рассматривается вопрос об идейно- ideological and creative evolution of famous творческой эволюции известных русских Russian poets at a turning point in the history of поэтов на переломном этапе истории ХХ the twentieth century - during the years of the столетия – в годы активного формирования active formation of a totalitarian state system тоталитарного государственного устройства и and its aesthetic socialist-realist doctrine. его эстетической соцреалистической Revolutionary maximalism, the idea of a доктрины. Революционный максимализм, идея complete renewal of all being, came not only полного обновления всего бытия шла не только from Marxism and the Bolsheviks, but was also от марксизма и большевиков, но prepared by literature, long before the подготавливалась и литературой, задолго до revolution, it had already “artistically matured” революции уже «вызрела» художественно в in the poetry of Alexander Blok, Sergey поэзии Александра Блока, Сергея Есенина, Yesenin, Osip Mandelstam, Vladimir Осипа Мандельштама, Владимира Mayakovsky and many others. -

Construction and Tradition: the Making of 'First Wave' Russian

Construction and Tradition: The Making of ‘First Wave’ Russian Émigré Identity A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of History from The College of William and Mary by Mary Catherine French Accepted for ____Highest Honors_______________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Frederick C. Corney, Director ________________________________________ Tuska E. Benes ________________________________________ Alexander Prokhorov Williamsburg, VA May 3, 2007 ii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Part One: Looking Outward 13 Part Two: Looking Inward 46 Conclusion 66 Bibliography 69 iii Preface There are many people to acknowledge for their support over the course of this process. First, I would like to thank all members of my examining committee. First, my endless gratitude to Fred Corney for his encouragement, sharp editing, and perceptive questions. Sasha Prokhorov and Tuska Benes were generous enough to serve as additional readers and to share their time and comments. I also thank Laurie Koloski for her suggestions on Romantic Messianism, and her lessons over the years on writing and thinking historically. Tony Anemone provided helpful editorial comments in the very early stages of the project. Finally, I come to those people who sustained me through the emotionally and intellectually draining aspects of this project. My parents have been unstinting in their encouragement and love. I cannot express here how much I owe Erin Alpert— I could not ask for a better sounding board, or a better friend. And to Dan Burke, for his love and his support of my love for history. 1 Introduction: Setting the Stage for Exile The history of communities in exile and their efforts to maintain national identity without belonging to a recognized nation-state is a recurring theme not only in general histories of Europe, but also a significant trend in Russian history. -

Editorial: Postanarchism

Editorial: Postanarchism SAUL NEWMAN Postanarchism is emerging as an important new current in anarchist thought, and it is the source of growing interest and debate amongst anarchist activists and scholars alike, as well as in broader academic circles. Given the number of internet sites, discussion groups, and new books and journal publications appearing on postanarchism, it is time that the challenges it poses to classical anarchist thought and practice are taken more seriously. Postanarchism refers to a wide body of theory – encompassing political theory, philosophy, aesthetics, literature and film studies – which attempts to explore new directions in anarchist thought and politics. While it includes a number of different perspectives and trajectories, the central contention of postanarchism is that classical anarchist philosophy must take account of new theoretical directions and cultural phenomena, in particular, postmodernity and poststructuralism. While these theoretical categories have had a major impact on different areas of scholarship and thought, as well as politics, anarchism tends to have remained largely resistant to these developments and continues to work within an Enlightenment humanist epistemological framework1 which many see as being in need of updating. At the same time, anarchism – as a form of political theory and practice – is becoming increasingly important to radical struggles and global social movements today, to a large extent supplanting Marxism. Postanarchism seeks to revitalise anarchist theory in light of these new struggles and forms of resistance. However, rather than dismissing the tradition of classical anarchism, postanarchism, on the contrary, seeks to explore its potential and radicalise its possibilities. It remains entirely consistent, I would suggest, with the libertarian and egal- itarian horizon of anarchism; yet it seeks to broaden the terms of anti-authoritarian thought to include a critical analysis of language, discourse, culture and new modalities of power. -

Letter to Sergey Nechayev

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Letter to Sergey Nechayev Mikhail Bakunin 1870 2 June 1870 Locarno DEAR FRIEND, I now address you and, through you, your and our Committee. I trust that you have now reached a safe place where, free from petty squabbles and cares, you can quietly consider your own and our common situation, the situation of our common cause. Let us begin by admitting that our first campaign which started in 1869 is lost and we are beaten. Beaten because of two main Mikhail Bakunin causes; first – the people, who we had every right to hope would Letter to Sergey Nechayev rise, did not rise. It appears that its cup of suffering, the mea- 1870 sure of its patience, has not yet overflowed. Apparently no self- Retrieved on 2020-08-26 from https://sovversiva.wordpress.com/ confidence, no faith in its rights and its power, has yet kindled 2011/12/30/bakunin-letter-to-sergey-nechayev/ within it, and there were not enought men acting in common and From Michael Confino: “Daughter of a Revolutionary: natalie dispersed throughout Russia capable of arousing this confidence. Herzen and the Bakunin/Nechayev Circle”, transl. by Hilary Second cause: our organization was found wanting both in quality Sternberg and Lydia Bott. Library Press, LaSalle, Illinois 1974. and quantity of its members and in its structure. That is why we were defeated and lost much strength and many valuable people. usa.anarchistlibraries.net This is an undisputable fact which we ought to realize without equivocation in order to make it a point departure for further de- liberations and deeds. -

3 Joining the International War Against Anarchism the Dutch Police and Its Push Towards Transnational Cooperation, 1880–1914

3 Joining the international war against anarchism The Dutch police and its push towards transnational cooperation, 1880–1914 Beatrice de Graaf* and Wouter Klem Introduction The Netherlands were much less targeted by anarchist violence than France, the Russian Empire, Spain, Italy, the United States or Germany.1 No heads of state or ministers were targeted, no casualties fell. Archival records, however, do reveal a number of reports and incidents regarding anarchist violence and visiting anarchists from abroad. The Dutch socialist leader Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis pointed in his autobiography from 1910 to the spurious contacts he had with (violent) anarchists comrades from Russia or Germany.2 Not much has been written about Dutch experiences with anarchist violence. Literature on the socialist movement does mention its clashes with anarchist ideology and activists, but remains silent on the violent aspects and international contacts between fugitive dynamitards in the Netherlands and well-known socialists such as Domela Nieuwenhuis.3 Even a recent biography on Domela Nieuwenhuis only touches upon his contacts in the anarchist scene in passing, and avoids discussing his ambivalent attitude towards political violence.4 In this chapter, some first findings are presented on the struggle against anarchist violence in the Netherlands around the end of the nineteenth century. The hypothesis is that this struggle should not merely be described as a reaction to concrete incidents and attacks, but should also be considered an expression of administrative and political agenda-setting, closely connected to the ambition of creating a modern, centralized and standardized police force, with corresponding mission statements and security ideas. -

Appendix! Fyodor Dostoevsky and Vladimir Solovyov*

Appendix! Fyodor Dostoevsky and Vladimir Solovyov* (In memory of Dr Nicolas M. Zernov, 1898-1980) The volume and scope of critical and commentarial literature devoted to Dostoevsky's thought in the century since his death is clear evidence of the richness and complexity encountered in his works. In the figure of Vladimir Solovyov - both in his person and his writings - we also encounter a high degree of complexity. Tracing the patterns of his thought, we find certain tensions and a number of striking incongruities. Here was - a man who was, at heart, a monarchist, but aroused the anger and suspicions of the Tsar and Holy Synod through his advocacy of theocratic government; a man who embraced so much that was characteristic of the Slavophiles, and yet was a staunch supporter of their arch-enemy, Peter the Great; a man so seemingly keen to reaffirm the worth of contemplative spirituality, but who personally resisted the decision to join a monastery, a step that he at one time regarded as 'flight' from the world. Those who knew Solovyov at first hand stressed what they regarded either as his sanctity or his eccentricity (his chudachestvo ). Accounts of the excitement generated by his university lectures on philosophy certainly show that he commanded a surprising degree of authority and respect. On the other hand, Solovyov had to contend with numerous uncharitable gibes and with accusations to the effect that he had set himself up as a 'prophet'. Perhaps his best response to adverse criticism of this kind was to deflate his *A Paper delivered at the VI Symposium of the International Dostoevsky Society, 9-16 August 1986, University of Nottingham. -

How Should One Evaluate the Soviet Revolution?

A&K Analyse & Kritik 2017; 39(2):199–221 Vittorio Hosle*¨ How Should One Evaluate the Soviet Revolution? https://doi.org/10.1515/auk-2017-0013 Abstract: The essay begins by discussing different ways of evaluating and making sense of the Soviet Revolution from Crane Brinton to Hannah Arendt. In a sec- ond part, it analyses the social, political and intellectual background of tsarist Russia that made the revolution possible. After a survey of the main changes that occurred in the Soviet Union, it appraises its ends, the means used for achieving them, and the unintended side-effects. The Marxist philosophy of history is inter- preted as an ideological tool of modernization attractive to societies to which the liberal form of modernization was precluded. Keywords: Ethical evaluation of social events, Soviet revolution, continuities be- tween pre-revolutionary and Soviet Russia 1 Introduction We may want to let the short twentieth century begin in 1914 or in 1917, but the So- viet Revolution will remain one of the most important events in the past century. To its comprehensive evaluation a century after the fact, perhaps a philosopher may contribute something useful. For the Soviet Revolution is, first, such a com- plex phenomenon that the perspectives of a single discipline, and even of various single disciplines juxtaposed to each other, will miss something important about this historical event. A philosopher, although a dilettante concerning each indi- vidual facet of the phenomenon, may enjoy a bird’s eye view, which can never replace but can maybe complement the specialists’ analyses. There is, second, the need for a normative evaluation of what happened to the Soviet Union and Russia in the course of the last hundred years. -

Poetry and Psychiatry

POETRY AND PSYCHIATRY Essays on Early Twentieth-Century Russian Symbolist Culture S t u d i e S i n S l av i c a n d R u ss i a n l i t e R at u R e S , c u lt u R e S , a n d H i S to Ry Series Editor: Lazar FLeishman (Stanford University) POETRY a n d PSYCHIATRY Essays on Early Twentieth-Century Russian Symbolist Culture Magnus L junggren Translated by Charles rougle Boston / 2014 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2014 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-61811-350-4 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61811-361-0 (electronic) ISBN 978-1-61811-369-6 (paper) Book design by Ivan Grave On the cover: Sergey Solovyov and Andrey Bely, 1904. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2014 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W.