Studies in Cern History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 1998, Vol

S T A N F O R D L I N E A R A CCELERATOR CENTER Spring 1998, Vol. 28, No.1 A PERIODICAL OF PARTICLE PHYSICS SPRING 1998 VOL. 28, N UMBER 1 Editors RENE DONALDSON, BILL KIRK Contributing Editors MICHAEL RIORDAN, GORDON FRASER JUDY JACKSON, PEDRO WALOSCHEK Editorial Advisory Board GEORGE BROWN, LANCE DIXON JOEL PRIMACK, NATALIE ROE ROBERT SIEMANN, GEORGE TRILLING KARL VAN BIBBER Illustrations TERRY A NDERSON Distribution Lake CRYSTAL TILGHMAN Soudan Superior Duluth The Beam Line is published quarterly by the MN Lake Stanford Linear Accelerator Center WI Michigan PO Box 4349, Stanford, CA 94309. Telephone: (650) 926-2585 Madison INTERNET: [email protected] MI FAX: (650) 926-4500 IA Issues of the Beam Line are accessible electronically on the World Wide Web at http://www.slac.stanford.edu/ Fermilab pubs/beamline IL IN SLAC is operated by Stanford University under contract with the U.S. Department of Energy. The opinions of the authors do not necessarily reflect the policy of the MO Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. Cover:The cover photo was taken in 1917, plus or minus about one year. The photographer is unknown or unre- membered. The young lad shown in the photo with his telescope in the garden of his home in Pretoria, South Africa, is Alan Cousins, at the age of about fourteen (he was born in 1903). Dr. Cousins’ first contribution to the astronomical literature was published in 1924. Seventy-four years have passed since then, but Alan William James Cousins is still at work at his home base, the South African Astronomical Observatory (SAAO), having recently published his latest paper (“Atmospheric Extinc- tion,” The Observatory, April 1998). -

I~ Ml 11111111 CM-P00043005

CHS-16 May 1985 CERN LIBRARIES, GENEY A -'°I Cf.l ::i:: u 11111111111111111~111~11111111111'1 ~II I~ I~ ml 11111111 CM-P00043005 STUDIES IN CERN HISTORY From the provisional organization to the permanent CERN May 1952 - September 1954 II. Case studies of some important decisions. John Krige *> GENEVA 1985 The Study of CERN History is a project financed by Institutions in several CERN Member Countries. This report presents preliminary findings, and is intended for incorporation into a more comprehensive study of CERN's history. It is distributed primarily to historians and scientists to provoke discussion, and no part of it should be cited or reproduced without written permission from the Team Leader. Comments are welcome and should be sent to: Study Team for CERN History c/oCERN CH-1211GENEVE23 Switzerland © Copyright Study Team for CERN History, Geneva 1985 CHS-16 May 1985 STUDIES IN CERN HISTORY From the provisional organization to the permanent CERN May 1952 - September 1954 II. Case studies of some important decisions. John Krige*) GENEVA 1985 *) Supported by a grant from the JOINT ESRC/SERC COMMITTEE, United Kingdom. The Study of CERN History is a project financed by Institutions in several CERN Member Countries. This report presents preliminary findings, and is intended for incorporation into a more comprehensive study of CERN's history. It is distributed primarily to historians and scientists to provoke discussion, and no part of it should be cited or reproduced without written permission from the Team Leader. Comments are welcome and should be sent to: Study Team for CERN History c/oCERN CH-1211 GENEVE 23 Switzerland © Copyright Study Team for CERN History, Geneva 1985 CERN - Service d'information scientifique - 300 - juillet 1985 From the provisional organization to the permanent CERN May 1952 - September 1954 II. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Goede humor, slechte smaak: een sociologie van de mop Kuipers, G.M.M. Publication date 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kuipers, G. M. M. (2001). Goede humor, slechte smaak: een sociologie van de mop. Boom. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:24 Sep 2021 LITERATUUR R Alford,, Finnegan & Richard Alford 19811 A Holo-cultural Study of Humor. Ethos9(2), 149-164. Ambrose,, Anthony 19633 Age of Onset of Ambivalence in Early Childhood: Indications from the Study of Laughter. JournalJournal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 4, 167-181. Anoniem m 18755 Mijn oom de majoor. In: Almanak van het Leidsche Studentencorps, 111-113. Leiden: P. -

Cornelis J. Bakker

Cornelis J. Bakker Autor(en): [s.n.] Objekttyp: Obituary Zeitschrift: Archives des sciences [1948-1980] Band (Jahr): 14 (1961) Heft 1 PDF erstellt am: 30.09.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch NÉCROLOGIE 139 La séance administrative est suivie de la séance publique qui s'ouvre par la lecture des nécrologies de MM. Cornelis Bakker et Arnold Borloz, présentées par MM. Poldini et Lanterno. Puis le nouveau président, M. Emile Dottrens, présente une conférence qu'on voudrait voir mise à la disposition d'un public plus étendu et intitulée: « La place de l'espèce humaine dans la nature ». -

Versione 3-6-2003

Department of Political Science Master’s Degree in International Relations Chair of History of the Americas TOMORROW THE STARS Italian Space Policy between the US and Europe 1954 - 1988 SUPERVISOR: CANDIDATE: Prof. Gregory Alegi Andrea Urbano ASSISTANT SUPERVISOR: Student ID 623972 Prof. Federico Niglia ACADEMIC YEAR 2014/2015 2 “The Space adventure is no more an episode of a single nation. Supranational collaboration and multidisciplinary research are increasingly necessary” Luigi Broglio 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgments .................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 6 Chapter I - Space: The new front in the Cold War ............................................... 14 1 . The United States toward the Moon Conquest ..................................... 15 2. Eastern Block Strategy in the “Space Race” ...................................... 36 Chapter II – The Beginning of the Italian Space Policy: “The Broglio Era” ........ 54 1. Relations between the US and Italy in the San Marco Project ............. 55 2. San Marco 2 - The beginning of the Italian Equatorial Space Launches ................................................................................................. 68 3. From San Marco 3 to the end of the Santa Rita Space Launches ........ 74 Chapter III – The difficult dialogue between Academics and Industries The new European concepts of Space ............................................. -

CERN – from Birth to Success

1 CERN – from birth to success 1 Herwig Schopper CERN and University of Hamburg A historical review is given of the development of CERN from its foundation to the present from a personal view of the author. Keywords: International organisation, accelerators, colliders, detectors, management. 1.CERN – a unique organization In each volume of RAST an article entitled “person of the volume” is published describing a large laboratory shaped largely by that person. When I was asked to write an article about CERN it was clear that this was impossible since so many personalities have played an essential role over the more than 50 years of CERN’s history, from its establishment to the most recent successes. Indeed there has always been a smooth transition from one Director General to the next, while project leaders have successively passed his tasks on smoothly to their successors. This is the way of CERN, whose international nature has meant that the Organization has had to accommodate a range of approaches, traditions and languages right from the start.1 From its very beginning CERN was a unique organisation based on two quite different initiatives. European physicists started the first initiative as early as 1946. They realized that competition with the USA was only possible if European countries2 joined forces. The first discussions were launched in the framework of UNESCO by Eduardo Amaldi from Italy3, the two French physicists Pierre Auger and Lew Kowarski and the American, Isidor Rabi. A second, and rather independent, initiative that is much less well known was that of the Swiss writer Denis de Rougemont who had spent the war at Princeton where he had met and interviewed Einstein. -

'We Vieren Het Pas Als Iedereen Terug

‘We vieren het pas als iedereen terug is’ RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN ‘We vieren het pas als iedereen terug is’ Terschelling in de Tweede Wereldoorlog Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Letteren aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 1 maart 2007 om 16.15 uur door Johan van der Wal geboren op 11 juli 1946 te Harlingen Promotores: Prof. dr. D.F.J. Bosscher Prof. dr. M.G.J. Duijvendak Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. dr. J.C.H. Blom Prof. dr. F.S. Gaastra Prof. dr. P. Kooij ISBN: 978 90 3672 9741 NUR-code 689 Woord vooraf Zoals meer dissertaties, kent ook deze een lange voorgeschiedenis. In feite startte die al op 31 maart 1930, toen mijn vader in Amsterdam aanmonsterde op het ss ‘Venezuela’. Hij was een ty- pisch slachtoffer van de economische crisis in die periode. Het zonneschermfabriekje dat hij in Harlingen als jonge ondernemer was gestart raakte in korte tijd failliet. Hij ging echter niet bij de pakken neerzitten maar spoedde zich direct naar de hoofdstad toen hij hoorde dat de Konink- lijke Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij schepelingen zocht. Als scheepstimmerman ging hij het zeegat uit, een beroep dat hij tot aan zijn pensionering in 1964 zou blijven uitoefenen. Zo maakte mijn vader, Lolke Johannes van der Wal (1904-1978) ook de Tweede Wereldoorlog op zee mee. De duur van het reisje van zes weken dat hij in het vroege voorjaar van 1940 aanving liep dan ook uit tot bijna zes jaar. De schepen waarop hij in de oorlog voer waren, net als de zeelieden zelf, in geallieerde dienst. -

First Name Last Name City State Michael O'neill DPO AE Cornelis

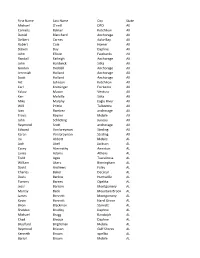

First Name Last Name City State Michael O'neill DPO AE Cornelis Bakker Ketchikan AK Daniel Blanchard Anchorage AK Delbert Carnes Auke Bay AK Robert Cole Homer AK Steven Day Daphne AK John Ellison Faiebanks AK Randall Farleigh Anchorage AK John Hardwick Sitka AK Gordon Heddell Anchorage AK Jeremiah Holland Anchorage AK Scott Holland Anchorage AK Art Johnson Ketchikan AK Carl Kretsinger Fairbanks AK Yakov Mazon Ventura AK Ken Melville Sitka AK Mike Murphy Eagle River AK Willi Prittie Talkeetna AK Ivan Ramirez anchorage AK Travis Rayner Mobile AK John Schlicting Juneau AK Raymond Scott anchorage AK Edward Von breyman Sterling AK Karen Von breyman Sterling AK Ira Abbott Mobile AL Josh Abell Jackson AL Casey Abernathy Anniston AL Lance Adams Athens AL Todd Agee Tuscaloosa AL William Akers Birmingham AL David Andrews Foley AL Charles Baker Decatur AL Davis Barlow Huntsville AL Tommy Barnes Opelika AL Jessr Barrom Montgomery AL Murrsy Beck Mountain Brook AL James Bennett Montgomery AL Kevin Bennett Hazel Green AL Brian Blackman Sterrett AL Sheldon Bradley Daphne AL Michael Bragg Randolph AL Chad Breaux Daphne AL Bradford Brightman Mobile AL Raymond Brisson Gulf Shores AL Kenneth Brown opelika AL Barry l. Brown Mobile AL Raymond Brown Lillian AL Bill Buchannon jr. Alexander City AL Eric Budinich Mobile AL Robert Burns Warrior AL Robert Burton Orange Beach AL Haas Byrd Tuscaloosa AL Cleveland Callaway Daphne AL Oliver Carlota Athens AL Ronnie Carlton Vestavia AL Randy Carnley theodore AL Dennis Carroll Mobile AL Thomas Carter Birmingham AL Gerald -

Geschichte Des CERN

i Michael Krause: Wo Menschen und Teilchen aufeinanderstoßen — i Chap. c01 — 2013/6/26 —page1 —le-tex i i 1 Geschichte des CERN »Je weiter man zurückblicken kann, desto weiter wird man vorausschauen.« Winston Spencer Churchill (1874–1965, Nobelpreis für Literatur 1953) Die Gründungsgeschichte des CERN, der Europäischen Organi- sation für Kernforschung, enthüllt in vielen historisch und wissen- schaftlich interessanten Details die Einzigartigkeit dieses Projekts. CERN ist das erste Joint Venture eines nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg langsam wieder zusammenwachsenden Europa und ein Sinnbild für die Fruchtbarkeit des europäischen Gedankens, der sich in der Geschichte des CERN als eine der überzeugendsten Grundideen be- wiesen hat. Viele der Strukturen des heutigen CERN lassen sich auf die Geschichte seiner Gründung zurückverfolgen und dadurch ver- ständlich machen. In der Gründungsphase des CERN entsteht der Geist, der noch heute an diesem auf der ganzen Welt einzigartigen Wissenschaftsstandort zu verspüren ist. Der Geist Europas – die Züricher Rede Churchills Winston Churchill, seit dem Jahr 1900 Mitglied des englischen Un- terhauses und Premierminister Englands ab 1940,warnochwährend der Potsdamer Konferenz, auf der wichtige Entscheidungen über das weitere Vorgehen der Alliierten USA, Russland und Großbritanni- en in Deutschland und gegen Japan entschieden wurden, bei den Wahlen zum britischen Unterhaus abgewählt worden. Er musste sei- nen Posten als Premierminister an den Labour-Politiker Clemens Att- lee abgeben. Churchill blieb weiterhin politisch aktiv und präsentier- te im März 1946 seineIdeevomEisernenVorhang,diewährenddes Kalten Krieges das Bild Europas und die Politik zwischen Ost und West bestimmen sollte. Am 19. September 1946 hielt Churchill vor Studenten der Züri- cher Universität seine berühmt gewordene Züricher Rede. -

Download De Pdf Van Dit Proefschrift

‘We vieren het pas als iedereen terug is’ RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN ‘We vieren het pas als iedereen terug is’ Terschelling in de Tweede Wereldoorlog Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Letteren aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 1 maart 2007 om 16.15 uur door Johan van der Wal geboren op 11 juli 1946 te Harlingen Promotores: Prof. dr. D.F.J. Bosscher Prof. dr. M.G.J. Duijvendak Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. dr. J.C.H. Blom Prof. dr. F.S. Gaastra Prof. dr. P. Kooij ISBN: 978 90 3672 9741 NUR-code 689 Woord vooraf Zoals meer dissertaties, kent ook deze een lange voorgeschiedenis. In feite startte die al op 31 maart 1930, toen mijn vader in Amsterdam aanmonsterde op het ss ‘Venezuela’. Hij was een ty- pisch slachtoffer van de economische crisis in die periode. Het zonneschermfabriekje dat hij in Harlingen als jonge ondernemer was gestart raakte in korte tijd failliet. Hij ging echter niet bij de pakken neerzitten maar spoedde zich direct naar de hoofdstad toen hij hoorde dat de Konink- lijke Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij schepelingen zocht. Als scheepstimmerman ging hij het zeegat uit, een beroep dat hij tot aan zijn pensionering in 1964 zou blijven uitoefenen. Zo maakte mijn vader, Lolke Johannes van der Wal (1904-1978) ook de Tweede Wereldoorlog op zee mee. De duur van het reisje van zes weken dat hij in het vroege voorjaar van 1940 aanving liep dan ook uit tot bijna zes jaar. De schepen waarop hij in de oorlog voer waren, net als de zeelieden zelf, in geallieerde dienst. -

Jul/Aug 2019 Edition

CERNJuly/August 2019 cerncourier.com COURIERReporting on international high-energy physics WLCOMEE GELL-MANN’S CERN Courier – digital edition COLOURFUL LEGACY Welcome to the digital edition of the July/August 2019 issue of CERN Courier. n p When CERN was just five years old, and the Proton Synchrotron was preparing for beams, Director-General Cornelis Bakker founded a new Λ Σ0 periodical to inform staff what was going on. It was eight-pages long with a Σ– Σ+ print run of 1000, but already a section called “Other people’s atoms” carried news from other labs and regions. Sixty years and almost 600 Couriers later, high-energy physicists are plotting a new path into the unknown, with the – 0 + update of the European Strategy bringing into focus how much traditional K0 K+ Ξ Ξ K*0 K* thinking is shifting, with new ideas and strong opinions in abundance. η0 –0 The first mention of quarks in theCourier was in March 1964, a few π– π+ ρ– ρp ρ+ months after they were dreamt up almost simultaneously on either side of 0 0 0 ω0 ϕϕ0 the Atlantic by George Zweig and Murray Gell-Mann, who passed away in ηʹ π May, and whose wide-ranging legacy is explored in this issue. Back then, the – 0 idea of fractionally charged, sub-nucleonic entities seemed preposterous. K– K0 K* K* It’s a reminder of how difficult it is to know what will be the next big thing – 0 + ++ in the fundamental-exploration business. On other pages, LHCb unfolds Δ Δ Δ Δ a ground-breaking analysis of CP violation in three-body B+ decays, nonagenarian former CERN Director-General Herwig Schopper reflects on lessons from LEP, and Nick Mavromatos and Jim Pinfold report on the cut and thrust of a Royal Society meeting on topologically non-trivial solutions of quantum field theory. -

Hsduwphqw 8Qlyhuvlw\ Ri $Dukxv

+LVWRU\RI6FLHQFH'HSDUWPHQW 8QLYHUVLW\RI$DUKXV KLAUS RASMUSSEN Det danske engagement i CERN 1950-70 +RVWD1R :RUNLQ3URJUHVV Hosta (History Of Science and Technology, Aarhus) is a series of publications initiated in 2000 at the History of Science Department at the University of Aarhus in order to provide opportunity for historians of science and technology outside the Department to get a glimpse of some of the ongoing or recent works at the Department by reserachers and advanced students. As most issues contain work in progress, comments to the authors are greatly valued. Publication is only made electronically on the web site of the Department (www.ifa.au.dk/ivh/hosta/home.dk.htm). The issues can freely be printed as pdf-documents. The web site also contains a full list of issues. ISSN: 1600-7433 History of Science Department University of Aarhus Ny Munkegade, building 521 DK-8000 Aarhus C Denmark English summary This thesis is a narrative about the Danish involvement in the emergence of the joint European collaboration CERN. Its primary objective is to describe events relating to CERN, in which Danish scientists, politicians and government officials took part. The secondary objective is to interpret the events in terms of Big Science characteristics, to see how a small country reacted to this new scale of scientific investigations. In the years from 1950 to 1954 Danish scientists, and most prominently Niels Bohr, managed to wield substantial influence in the debate concerning how this European endeavor should be carried out. Even though the Danes were not successful in promoting their preferred style of cooperation, they managed to obtain a relatively central part of it: The Theoretical Study group located at Niels Bohr’s institute in Copenhagen.