Institutional Breton Language Policy After Language Shift

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bro Nevez 155 As You Will Read in These Pages of Bro Nevez, Brittany

No. 155 Sept. 2020 1 Editorial Bro Nevez 155 As you will read in these pages of Bro Nevez, Brittany has not stood still during the Covid-19 pandemic. As a September 2020 more rural area it has been less impacted by other areas of France and Europe, but nevertheless Brittany’s economy has been hit hard. While tourism ISSN 0895 3074 flourished other areas suffered, and this was especially so in the cultural world where festivals, concerts and festoù-noz were very limited or cancelled. But I have EDITOR’S ADRESS & E-MAIL no doubt that dancing and music making and the socializing that is so much a central part of these will be back as soon as Bretons are able to amp things Lois Kuter, Editor back up. LK Bro Nevez 605 Montgomery Road On the Cover – See a book review of this new work by Ambler, PA 19002 U.S.A. Thierry Jigourel later in this issue of Bro Nevez (page 9). 215 886-6361 [email protected] A New School Year for the Breton Language U.S. ICDBL website: www.icdbl.org The Ofis Publik ar Brezhoneg posts numbers each year for the school year and the presence of Breton in the classroom. Despite Covid-19, bilingual programs The U.S. Branch of the International Committee for the continue to grow with 20 new sites at the pre- and Defense of the Breton Language (U.S. ICDBL) was primary school levels this fall. incorporated as a not-for-profit corporation on October 20, 1981. Bro Nevez (“new country” in the Breton language) is In the Region of Brittany (four departments) under the Rennes Academy Diwan opened a third Breton the newsletter produced by the U.S. -

PDF Download Enacting Brittany 1St Edition Pdf Free Download

ENACTING BRITTANY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patrick Young | 9781317144076 | | | | | Enacting Brittany 1st edition PDF Book At Tregor, boudins de Calage hand-bricks were the typical form of briquetage, between 2. Since , Brittany was re-established as a Sovereign Duchy with somewhat definite borders, administered by Dukes of Breton houses from to , before falling into the sphere of influence of the Plantagenets and then the Capets. Saint-Brieuc Main article: Duchy of Brittany. In the camp was closed and the French military decided to incorporate the remaining 19, Breton soldiers into the 2nd Army of the Loire. In Vannes , there was an unfavorable attitude towards the Revolution with only of the city's population of 12, accepting the new constitution. Prieur sought to implement the authority of the Convention by arresting suspected counter-revolutionaries, removing the local authorities of Brittany, and making speeches. The rulers of Domnonia such as Conomor sought to expand their territory including holdings in British Devon and Cornwall , claiming overlordship over all Bretons, though there was constant tension between local lords. It is therefore a strategic choice as a case study of some of the processes associated with the emergence of mass tourism, and the effects of this kind of tourism development on local populations. The first unified Duchy of Brittany was founded by Nominoe. This book was the world's first trilingual dictionary, the first Breton dictionary and also the first French dictionary. However, he provides less extensive access to how ordinary Breton inhabitants participated in the making of Breton tourism. And herein lies the central dilemma that Young explores in this impressive, deeply researched study of the development of regional tourism in Brittany. -

Copyright by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey 2010

Copyright by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey 2010 The Dissertation Committee for Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Planning language practices and representations of identity within the Gallo community in Brittany: A case of language maintenance Committee: _________________________________ Jean-Pierre Montreuil, Supervisor _________________________________ Cinzia Russi _________________________________ Carl Blyth _________________________________ Hans Boas _________________________________ Anthony Woodbury Planning language practices and representations of identity within the Gallo community in Brittany: A case of language maintenance by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2010 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents and my family for their patience and support, their belief in me, and their love. I would like to thank my supervisor Jean-Pierre Montreuil for his advice, his inspiration, and constant support. Thank you to my committee members Cinzia Russi, Carl Blyth, Hans Boas and Anthony Woodbury for their guidance in this project and their understanding. Special thanks to Christian Lefeuvre who let me stay with him during the summer 2009 in Langan and helped me realize this project. For their help and support, I would like to thank Rosalie Grot, Pierre Gardan, Christine Trochu, Shaun Nolan, Bruno Chemin, Chantal Hermann, the associations Bertaèyn Galeizz, Chubri, l’Association des Enseignants de Gallo, A-Demórr, and Gallo Tonic Liffré. For financial support, I would like to thank the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin for the David Bruton, Jr. -

Celts and Celtic Languages

U.S. Branch of the International Comittee for the Defense of the Breton Language CELTS AND CELTIC LANGUAGES www.breizh.net/icdbl.htm A Clarification of Names SCOTLAND IRELAND "'Great Britain' is a geographic term describing the main island GAIDHLIG (Scottish Gaelic) GAEILGE (Irish Gaelic) of the British Isles which comprises England, Scotland and Wales (so called to distinguish it from "Little Britain" or Brittany). The 1991 census indicated that there were about 79,000 Republic of Ireland (26 counties) By the Act of Union, 1801, Great Britain and Ireland formed a speakers of Gaelic in Scotland. Gaelic speakers are found in legislative union as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and all parts of the country but the main concentrations are in the The 1991 census showed that 1,095,830 people, or 32.5% of the population can Northern Ireland. The United Kingdom does not include the Western Isles, Skye and Lochalsh, Lochabar, Sutherland, speak Irish with varying degrees of ability. These figures are of a self-report nature. Channel Islands, or the Isle of Man, which are direct Argyll and Bute, Ross and Cromarly, and Inverness. There There are no reliable figures for the number of people who speak Irish as their dependencies of the Crown with their own legislative and are also speakers in the cities of Edinburgh, Glasgow and everyday home language, but it is estimated that 4 to 5% use the language taxation systems." (from the Statesman's handbook, 1984-85) Aberdeen. regularly. The Irish-speaking heartland areas (the Gaeltacht) are widely dispersed along the western seaboards and are not densely populated. -

Options for Intervention at the Regional Level Taken Brittany As an Example1 Susanne Lesk (Vienna University of Economics and Business)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by JournaLIPP (Graduate School Language & Literature - Class of Language, LMU München) Institutional Work of Regional Language Movements: Options for Intervention at the Regional Level Taken Brittany as an Example1 Susanne Lesk (Vienna University of Economics and Business) Abstract According to the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, the Breton language is severely endangered. While there were over 1 million Breton speakers around 1950, only 194,500 remained in 2007. The annual decrease in Breton speakers by 8,300 cannot be compensated at present, leading to the crossing of the threshold of 100,000 Breton speakers in about a quarter of a century. The constitutional amendment in 2008, according, for the first time, an official status to regional languages in France, did not provide any real benefits either, except for a higher legitimacy for regional politicians and other actors of regional language movements to implement language- sensitive promotional measures. In this regard, the region of Brittany is a pioneer, as it has demonstrated a high commitment to the promotion of the Breton language since the mid-nineties. In this context, this paper investigates what possibilities exist for local- level authorities and other strategic actors in the field to encourage the social use of a regional language in all domains of life. First, the sociolinguistic situation in Brittany is outlined and evaluated using secondary data. Second, a qualitative study (in-depth interviews) was conducted to provide further insights into the interdependencies between the different actors in the field of the Breton language policy, and revealed options for policy instrument development by regional governments. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 447 692 FL 026 310 AUTHOR Breathnech, Diarmaid, Ed. TITLE Contact Bulletin, 1990-1999. INSTITUTION European Bureau for Lesser Used Languages, Dublin (Ireland). SPONS AGENCY Commission of the European Communities, Brussels (Belgium). PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 398p.; Published triannually. Volume 13, Number 2 and Volume 14, Number 2 are available from ERIC only in French. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) LANGUAGE English, French JOURNAL CIT Contact Bulletin; v7-15 Spr 1990-May 1999 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Ethnic Groups; Irish; *Language Attitudes; *Language Maintenance; *Language Minorities; Second Language Instruction; Second Language Learning; Serbocroatian; *Uncommonly Taught Languages; Welsh IDENTIFIERS Austria; Belgium; Catalan; Czech Republic;-Denmark; *European Union; France; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iceland; Ireland; Italy; *Language Policy; Luxembourg; Malta; Netherlands; Norway; Portugal; Romania; Slovakia; Spain; Sweden; Ukraine; United Kingdom ABSTRACT This document contains 26 issues (the entire output for the 1990s) of this publication deaicated to the study and preservation of Europe's less spoken languages. Some issues are only in French, and a number are in both French and English. Each issue has articles dealing with minority languages and groups in Europe, with a focus on those in Western, Central, and Southern Europe. (KFT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. N The European Bureau for Lesser Used Languages CONTACT BULLETIN This publication is funded by the Commission of the European Communities Volumes 7-15 1990-1999 REPRODUCE AND PERMISSION TO U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research DISSEMINATE THIS and Improvement BEEN GRANTEDBY EDUCATIONAL RESOURCESINFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) This document has beenreproduced as received from the personor organization Xoriginating it. -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

Standard Breton, Neo-Breton and Traditional Dialects Mélanie Jouitteau

Children Prefer Natives; A study on the transmission of a heritage language; Standard Breton, Neo-Breton and traditional dialects Mélanie Jouitteau To cite this version: Mélanie Jouitteau. Children Prefer Natives; A study on the transmission of a heritage language; Standard Breton, Neo-Breton and traditional dialects. Maria Bloch-Trojnar and Mark Ó Fionnáin. Centres and Peripheries in Celtic Linguistics, Peter Lang, pp.75, 2018, Sounds - Meaning - Commu- nication, 9783631770825. hal-02023362 HAL Id: hal-02023362 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02023362 Submitted on 27 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Children Prefer Natives A study on the transmission of a heritage language; Standard Breton, 1 Neo-Breton and traditional dialects Mélanie Jouitteau IKER, CNRS, UMR 5478 Abstract I present a linguistic effect by which heritage language speakers over- represent traditional input in their acquisition system. I propose that native young adults children of the missing link generation disqualify the input of insecure L2 speakers of Standard and prefer the input of linguistically secure speakers in the making of their own generational variety. Given the socio-linguistics of Breton, this effect goes both against statistical and sociological models of acquisition because speakers disregard features of Standard Breton, which is the socially valorised variety accessible to them and valued by school and media. -

Scandinavian Loanwords in English in the 15Th Century

Studia Celtica Posnaniensia Vol 4 (1), 2019 doi: 10.2478/scp-2019-0004 GENDER-FAIR LANGUAGE IN A MINORITY SETTING: THE CASE OF BRETON1 MICHAEL HORNSBY Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań ABSTRACT This paper explores the use of the Breton language (Brittany, North-West France) in contexts where speakers wish to signal their commitment to social equality through their linguistic practices. This is done with reference to examples of job advertisements which have pioneered the use of gender-fair language in Breton. Linguistic minorities are often portrayed as clinging to the past. This paper, however, sheds a different light on current minority language practices and demonstrates a progressive and egalitarian response to modernity among some current speakers of Breton, in their attempts to assume gender-fair stances. Key words: Breton, minority language, gender-fair language, new speakers 1. Introduction In this article, we examine first how linguistic minorities in France are somehow rendered invisible, or ‘erased’ (referring to Irving and Gal’s (2000) work on erasure) and then extend this sense of erasure to challenge the frequent imagined homogenization of minority groups, in which marginalized populations within identified minority groups are further erased. In Brittany, 1 The author would like to warmly thank Drs Julie Abbou (Aix-Marseille University), Joanna Chojnicka (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań) and Karolina Rosiak (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań) for their reader comments on the present article. © Copyright by The Faculty of English, Adam Mickiewicz University 60 M. Hornsby this has begun to be challenged through the emerging use of ‘gender-fair language’ to reflect the presence of people other than men in public and institutional life. -

Linguicide in the Digital Age: Problems and Possible Solutions

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College French Summer Fellows Student Research 7-22-2021 Linguicide in the Digital Age: Problems and Possible Solutions Michael Adelson Ursinus College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/french_sum Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Civil Law Commons, Comparative and Historical Linguistics Commons, French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons, Language Description and Documentation Commons, Modern Languages Commons, Other Law Commons, and the Typological Linguistics and Linguistic Diversity Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Adelson, Michael, "Linguicide in the Digital Age: Problems and Possible Solutions" (2021). French Summer Fellows. 3. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/french_sum/3 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in French Summer Fellows by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Linguicide in the Digital Age: Problems and Possible Solutions Michael Adelson Summer Fellows 2021 Ursinus College Advisor: Dr. Céline Brossillon Linguicide in the Digital Age 1 Abstract Language is perhaps the most fundamental, elemental biological function of human beings. Language communicates emotions, thoughts, ideas, innovations, hardships, and most importantly, is an expression of culture. With languages disappearing at an accelerated rate today, this paper serves to provide insight into the health and status of seven endangered languages and the methods for their linguistic rejuvenation. The languages in question are Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Irish, Hopi, Navajo, Breton, and Occitan. -

Project Manager's Note

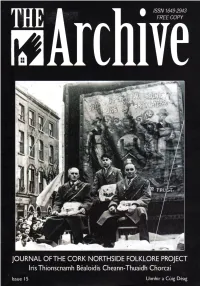

Project Manager’s Note As you may have already noticed, there are big changes in Issue #15 of The Archive. First, we have a new name and are now officially the Cork Northside Folklore Project, CNFP, making our identity in the wider world a little clearer. Secondly, we have made a dramatic visual leap into colour, Picking 'Blackas' 3 while retaining our distinctive black and white exterior. It was A Safe Harbour for Ships 4-5 good fun planning this combination, and satisfying being able Tell the Mason the Boss is on the Move 6-7 to use colour where it enhances an image. The wonders of dig- Street Games 8 ital printing make it possible to do this with almost no addi- The Day The President Came to Town 9 tional cost. We hope you approve! The Coppingers of Ballyvolane 10-11 The Wireless 11 As is normal, our team is always evolving and changing with Online Gaming Culture 12 the comings and goings of our FÁS staff, but this year we have Piaras Mac Gearailt, Cúirt na mBurdún, agus had the expansion of our UCC Folklore & Ethnology Depart- ‘Bata na Bachaille’ in Iarthar Déise 13 ment involvement. Dr Clíona O’Carroll has joined Dr Marie- Cork Memory Map 14-15 Annick Desplanques as a Research Director, and Ciarán Ó Sound Excerpts 16-17 Gealbháin has contributed his services as Editorial Advisor for Burlesque in Cork 18-19 this issue. We would like to thank all three of them very much Restroom Graffiti 19 for their time and energies. -

THE BRETON of the CANTON of BRIEG 11 December

THE BRETON OF THE CANTON OF BRIEC1 PIERRE NOYER A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Celtic Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2019 1 Which will be referred to as BCB throughout this thesis. CONCISE TABLE OF CONTENTS DETAILED TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ 3 DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................... 21 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS WORK ................................................................................. 24 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 29 2. PHONOLOGY ........................................................................................................................... 65 3. MORPHOPHONOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 115 4. MORPHOLOGY ....................................................................................................................... 146 5. SYNTAX .................................................................................................................................... 241 6. LEXICON.................................................................................................................................. 254 7. CONCLUSION.........................................................................................................................