Multilingual Early Language Transmission (MELT)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download Enacting Brittany 1St Edition Pdf Free Download

ENACTING BRITTANY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patrick Young | 9781317144076 | | | | | Enacting Brittany 1st edition PDF Book At Tregor, boudins de Calage hand-bricks were the typical form of briquetage, between 2. Since , Brittany was re-established as a Sovereign Duchy with somewhat definite borders, administered by Dukes of Breton houses from to , before falling into the sphere of influence of the Plantagenets and then the Capets. Saint-Brieuc Main article: Duchy of Brittany. In the camp was closed and the French military decided to incorporate the remaining 19, Breton soldiers into the 2nd Army of the Loire. In Vannes , there was an unfavorable attitude towards the Revolution with only of the city's population of 12, accepting the new constitution. Prieur sought to implement the authority of the Convention by arresting suspected counter-revolutionaries, removing the local authorities of Brittany, and making speeches. The rulers of Domnonia such as Conomor sought to expand their territory including holdings in British Devon and Cornwall , claiming overlordship over all Bretons, though there was constant tension between local lords. It is therefore a strategic choice as a case study of some of the processes associated with the emergence of mass tourism, and the effects of this kind of tourism development on local populations. The first unified Duchy of Brittany was founded by Nominoe. This book was the world's first trilingual dictionary, the first Breton dictionary and also the first French dictionary. However, he provides less extensive access to how ordinary Breton inhabitants participated in the making of Breton tourism. And herein lies the central dilemma that Young explores in this impressive, deeply researched study of the development of regional tourism in Brittany. -

Copyright by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey 2010

Copyright by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey 2010 The Dissertation Committee for Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Planning language practices and representations of identity within the Gallo community in Brittany: A case of language maintenance Committee: _________________________________ Jean-Pierre Montreuil, Supervisor _________________________________ Cinzia Russi _________________________________ Carl Blyth _________________________________ Hans Boas _________________________________ Anthony Woodbury Planning language practices and representations of identity within the Gallo community in Brittany: A case of language maintenance by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2010 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents and my family for their patience and support, their belief in me, and their love. I would like to thank my supervisor Jean-Pierre Montreuil for his advice, his inspiration, and constant support. Thank you to my committee members Cinzia Russi, Carl Blyth, Hans Boas and Anthony Woodbury for their guidance in this project and their understanding. Special thanks to Christian Lefeuvre who let me stay with him during the summer 2009 in Langan and helped me realize this project. For their help and support, I would like to thank Rosalie Grot, Pierre Gardan, Christine Trochu, Shaun Nolan, Bruno Chemin, Chantal Hermann, the associations Bertaèyn Galeizz, Chubri, l’Association des Enseignants de Gallo, A-Demórr, and Gallo Tonic Liffré. For financial support, I would like to thank the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin for the David Bruton, Jr. -

O N E Ücague

ISSN 0257-7860 SOp Sterling N r. 54 SUMMER 1986 ScRift-Celt ’86 CuiM^Nic^ aiR CRuaöal NaN DaoiNe AftGR EleCtiONS: Pause to tt}iNk BRitisIi BoMbiNq Mi stäke 'Oje iRisb iN ScotJaNö MilitaRisatioN o f CoRNwall iRisb LaNQuaqe News O n e ü c A G u e AIBA: CCYMUNN CEIU64CH • BRE1ZH: KE/RE KEUIEK Cy/URU: UNDEB CELMIDD 'EIRE: CONR4DH CEIITWCH K ER N O W : KESUNY/flNS KELTER • /VW NNINICQ/V1MEEYS CEITWGH ALBA na Tuirceis cuideachd. Chan fhaca Murchaidh Mar sin chunnaic iad na murtaireann a" sior an Cornach uair sam bith nach robh e a" dlüthachadh riutha. CUIMHNICH AIR smogadh na phiob aige. B'iad nan saighdearan Turcach. Bha “ Tha a" mhör-chuid den lompaireachd oifigear aca mu dhä fhichead bliadhna a Thurcach thairis air na h-Arabaich a 1ha fo dh'aois. Bha e lachdainn le stais (moustache) CRUADAL NAN ar-a-mach an aghaidh nan Turcach. Tuigidh mhör dhubh Ihiadhaich. Bha dag "na laimh. na Turcaich gu math gum bheil iad ann an Chunnaic Murchadh. Goff agus na DAOINE ... cunnart ro mhör." arsa Micheil. seachdnar saighdearan aca le oillt o'n uinneig "An robh na Turcaich daonnan fiadhaich uachdarach na bha a’dol seachad san t-sräid. ri daoine eile?" dh'fhaighnichd an Gaidheal. Ruitheadh an ceannard Turcach a stcach do "Chan eil idir. Bha iad daonnan ro fliad- gach laigh. Nuair a thilleadh e dh'eigheadh Aros sona bh'againn thall fhulangach a thaobh a h-uile creideamh san e aireamh air choireigin. An sin ruitheadh Airigh mhonaidh, innis bhö lompaireachd aca." grunn de shaighdearan furcach asteach agus Sgaoil ar sonas uainn air ball Ach chan eil an t-Arm daonnan gun thilleadh iad a-mach a' slaodadh grunnan de Mar roinneas gaoth nam fhuar-bheann ceö. -

Celts and Celtic Languages

U.S. Branch of the International Comittee for the Defense of the Breton Language CELTS AND CELTIC LANGUAGES www.breizh.net/icdbl.htm A Clarification of Names SCOTLAND IRELAND "'Great Britain' is a geographic term describing the main island GAIDHLIG (Scottish Gaelic) GAEILGE (Irish Gaelic) of the British Isles which comprises England, Scotland and Wales (so called to distinguish it from "Little Britain" or Brittany). The 1991 census indicated that there were about 79,000 Republic of Ireland (26 counties) By the Act of Union, 1801, Great Britain and Ireland formed a speakers of Gaelic in Scotland. Gaelic speakers are found in legislative union as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and all parts of the country but the main concentrations are in the The 1991 census showed that 1,095,830 people, or 32.5% of the population can Northern Ireland. The United Kingdom does not include the Western Isles, Skye and Lochalsh, Lochabar, Sutherland, speak Irish with varying degrees of ability. These figures are of a self-report nature. Channel Islands, or the Isle of Man, which are direct Argyll and Bute, Ross and Cromarly, and Inverness. There There are no reliable figures for the number of people who speak Irish as their dependencies of the Crown with their own legislative and are also speakers in the cities of Edinburgh, Glasgow and everyday home language, but it is estimated that 4 to 5% use the language taxation systems." (from the Statesman's handbook, 1984-85) Aberdeen. regularly. The Irish-speaking heartland areas (the Gaeltacht) are widely dispersed along the western seaboards and are not densely populated. -

A Critical Analysis of the Role of Community Sport in Encouraging the Use of the Welsh Language Among Young People Beyond the School Gate

A critical analysis of the role of community sport in encouraging the use of the Welsh language among young people beyond the school gate Lana Evans Thesis submitted to Cardiff Metropolitan University in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Cardiff School of Sport and Health Sciences, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff April 2019 Director of Studies: Dr Nicola Bolton Supervisors: Professor Carwyn Jones, Dr Hywel Iorwerth Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................ I ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... II PEER-REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS ............................................................................................................. III CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 The Regression of the Welsh Language during the Twentieth Century ......................................................... 2 Political Attempts to Reverse the Decline ..................................................................................................... -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 447 692 FL 026 310 AUTHOR Breathnech, Diarmaid, Ed. TITLE Contact Bulletin, 1990-1999. INSTITUTION European Bureau for Lesser Used Languages, Dublin (Ireland). SPONS AGENCY Commission of the European Communities, Brussels (Belgium). PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 398p.; Published triannually. Volume 13, Number 2 and Volume 14, Number 2 are available from ERIC only in French. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) LANGUAGE English, French JOURNAL CIT Contact Bulletin; v7-15 Spr 1990-May 1999 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Ethnic Groups; Irish; *Language Attitudes; *Language Maintenance; *Language Minorities; Second Language Instruction; Second Language Learning; Serbocroatian; *Uncommonly Taught Languages; Welsh IDENTIFIERS Austria; Belgium; Catalan; Czech Republic;-Denmark; *European Union; France; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iceland; Ireland; Italy; *Language Policy; Luxembourg; Malta; Netherlands; Norway; Portugal; Romania; Slovakia; Spain; Sweden; Ukraine; United Kingdom ABSTRACT This document contains 26 issues (the entire output for the 1990s) of this publication deaicated to the study and preservation of Europe's less spoken languages. Some issues are only in French, and a number are in both French and English. Each issue has articles dealing with minority languages and groups in Europe, with a focus on those in Western, Central, and Southern Europe. (KFT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. N The European Bureau for Lesser Used Languages CONTACT BULLETIN This publication is funded by the Commission of the European Communities Volumes 7-15 1990-1999 REPRODUCE AND PERMISSION TO U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research DISSEMINATE THIS and Improvement BEEN GRANTEDBY EDUCATIONAL RESOURCESINFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) This document has beenreproduced as received from the personor organization Xoriginating it. -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

Notes on Gender and the Politics of the Irish Language in Northern Ireland

Notes on Gender and the Politics of the Irish Language in Northern Ireland andat Irish language events andgath- In Belfast gender roles are not so erings, I carried out 82 in-depth in- clear cut, and it has thus been more C'est h question Asgenres h I 'intprieur terviews with people involved with difficult to assess the impact of my du mouvement du renouveau A & the movement in avariety ofdifferent own gender on access to certain cir- &ngueen Zrlandcdu Nordquia inspirC capacities. I talked to activists, teach- cles and on other aspects of my re- cet amrtrcIc.L Luteure met m contraste ers, Irish language learners, and the search. The only domain to which I les observations parents ofchildren in the Irish schools, could not gain access was all-male faites par d'autres and took an oral history of each per- socializing, for example, in the pub. Gender patterns in the d~ffcheur~q~i$nt son's involvement with the language. But most Irish language social occa- revival movement were un travail ana- It came as no surprise, though, that sions involve both sexes, so this never logueaknsdkutres gender became an important consid- really became an issue. While there of interest because they eration during my field research. are certain organizations or groups both reinforced and While, as has been observed by so which tend to be male-dominated, broke stereotypes. Over the past dec- many female anthropologists before none are openly exclusive. ade or two inter- (Golde; Bell, Caplan, and Karim), My position in the community of est in the Irish lan- my gender was important to my ex- Gaeifgeoiri (Irish language enthusi- guage in Northern Ireland has in- perience as a researcher, I also noticed asts) and in West Belfast in general creased, particularly amongst the gender patterns in the revival move- changed part way through my field- nationalist1 community. -

Project Manager's Note

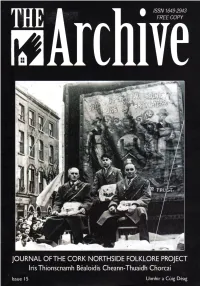

Project Manager’s Note As you may have already noticed, there are big changes in Issue #15 of The Archive. First, we have a new name and are now officially the Cork Northside Folklore Project, CNFP, making our identity in the wider world a little clearer. Secondly, we have made a dramatic visual leap into colour, Picking 'Blackas' 3 while retaining our distinctive black and white exterior. It was A Safe Harbour for Ships 4-5 good fun planning this combination, and satisfying being able Tell the Mason the Boss is on the Move 6-7 to use colour where it enhances an image. The wonders of dig- Street Games 8 ital printing make it possible to do this with almost no addi- The Day The President Came to Town 9 tional cost. We hope you approve! The Coppingers of Ballyvolane 10-11 The Wireless 11 As is normal, our team is always evolving and changing with Online Gaming Culture 12 the comings and goings of our FÁS staff, but this year we have Piaras Mac Gearailt, Cúirt na mBurdún, agus had the expansion of our UCC Folklore & Ethnology Depart- ‘Bata na Bachaille’ in Iarthar Déise 13 ment involvement. Dr Clíona O’Carroll has joined Dr Marie- Cork Memory Map 14-15 Annick Desplanques as a Research Director, and Ciarán Ó Sound Excerpts 16-17 Gealbháin has contributed his services as Editorial Advisor for Burlesque in Cork 18-19 this issue. We would like to thank all three of them very much Restroom Graffiti 19 for their time and energies. -

THE BRETON of the CANTON of BRIEG 11 December

THE BRETON OF THE CANTON OF BRIEC1 PIERRE NOYER A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Celtic Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2019 1 Which will be referred to as BCB throughout this thesis. CONCISE TABLE OF CONTENTS DETAILED TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ 3 DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................... 21 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS WORK ................................................................................. 24 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 29 2. PHONOLOGY ........................................................................................................................... 65 3. MORPHOPHONOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 115 4. MORPHOLOGY ....................................................................................................................... 146 5. SYNTAX .................................................................................................................................... 241 6. LEXICON.................................................................................................................................. 254 7. CONCLUSION......................................................................................................................... -

Nuachtlitir Cultúrtha Agus Teanga an CLG San Eoraip European GAA

Nuachtlitir Cultúrtha agus Teanga an CLG san Eoraip European GAA Language and Content Cultural Newsletter Réamhrá/Introduction 1 Imleabhar I Eagrán 1 The Cultural and Linguistic Impact of the Irish and the GAA in Saint Gallen 2 Lá Féile Bríde, 1 Feabhra 2012 Le foot Gaelique en Bretagne 6 Seachtain na Gaeilge sa Bhruiséil 9 Welcome to the Language and Cultural Newsletter of the GAA in continental Europe. The Estonian Fire Lynxes 11 Go raibh mile maith agaibh/many thanks to all who contributed to this first edition. If you would like to contribute to this newsletter by writing an article or simply by informing us of any cultural events your club might be involved in, please contact Caoimhe at: [email protected] Nuachtlitir CLG na hEorpa Imleabhar I Eagrán 1 RÉAMHRÁ Tá ana áthas orm an chéad INTRODUCTION I am delighted eagrán seo de nuachtlitir chultúrtha an CLG san to launch the first issue of the European GAA’s Eoraip a chur os bhur gcomhair. Is deis iontach cultural newsletter. This as a great opportunity é seo, ní hamháin chun teanga agus cultúr na not only to celebrate the language and culture nÉireannach atá lonnaithe ar Mhór-Roinn na of the Irish who are settled on the European hEorpa a chomóradh, ach chun aitheantas a continent but also to recognise the thabhairt d’ilteangachas agus d’ilchultúrthacht multilingualism and cultural diversity amongst lucht CLG san Eoraip leis. Tá saibhreas ar leith all GAA players in Europe. As European football idir theangacha agus chultúir againn i measc ár and hurling/camogie players, we are lucky to n-imreoirí peile agus have a cultural and linguistic richness at our iománaíochta/camógaíochta san Eoraip nach feet, a gift that GAA players in many other bhfuil ag lucht CLG in áit ar bith eile ar domhan places across the world do not. -

Orthographies and Ideologies in Revived Cornish

Orthographies and ideologies in revived Cornish Merryn Sophie Davies-Deacon MA by research University of York Language and Linguistic Science September 2016 Abstract While orthography development involves detailed linguistic work, it is particularly subject to non-linguistic influences, including beliefs relating to group identity, as well as political context and the level of available state support. This thesis investigates the development of orthographies for Cornish, a minority language spoken in the UK. Cornish is a revived language: while it is now used by several hundred people, it underwent language death in the early modern era, with the result that no one orthography ever came to take precedence naturally. During the revival, a number of orthographies have been created, following different principles. This thesis begins by giving an account of the development of these different orthographies, focusing on the context in which this took place and how contextual factors affected their implementation and reception. Following this, the situation of Cornish is compared to that of Breton, its closest linguistic neighbour and a minority language which has experienced revitalisation, and the creation of multiple orthographies, over the same period. Factors affecting both languages are identified, reinforcing the importance of certain contextual influences. After this, materials related to both languages, including language policy, examinations, and learning resources, are investigated in order to determine the extent to which they acknowledge the multiplicity of orthographies in Cornish and Breton. The results of this investigation indicate that while a certain orthography appears to have been established as a standard in the case of Breton, this cannot be said for Cornish, despite significant amounts of language planning work in this domain in recent years.