Whither Cross-Strait Relations? Convergence, Collision, and Reconciliation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater China: the Next Economic Superpower?

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Murray Weidenbaum Publications Government, and Public Policy Contemporary Issues Series 57 2-1-1993 Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower? Murray L. Weidenbaum Washington University in St Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Weidenbaum, Murray L., "Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower?", Contemporary Issues Series 57, 1993, doi:10.7936/K7DB7ZZ6. Murray Weidenbaum Publications, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers/25. Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy — Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1027, St. Louis, MO 63130. Other titles available in this series: 46. The Seeds ofEntrepreneurship, Dwight Lee Greater China: The 47. Capital Mobility: Challenges for Next Economic Superpower? Business and Government, Richard B. McKenzie and Dwight Lee Murray Weidenbaum 48. Business Responsibility in a World of Global Competition, I James B. Burnham 49. Small Wars, Big Defense: Living in a World ofLower Tensions, Murray Weidenbaum 50. "Earth Summit": UN Spectacle with a Cast of Thousands, Murray Weidenbaum Contemporary 51. Fiscal Pollution and the Case Issues Series 57 for Congressional Term Limits, Dwight Lee February 1993 53. Global Warming Research: Learning from NAPAP 's Mistakes, Edward S. Rubin 54. The Case for Taxing Consumption, Murray Weidenbaum 55. Japan's Growing Influence in Asia: Implications for U.S. Business, Steven B. Schlossstein 56. The Mirage of Sustainable Development, Thomas J. DiLorenzo Additional copies are available from: i Center for the Study of American Business Washington University CS1- Campus Box 1208 One Brookings Drive Center for the Study of St. -

Greater China Beef & Sheepmeat Market Snapshot

MARKET SNAPSHOT l BEEF & SHEEPMEAT Despite being the most populous country in the world, the proportion of Chinese consumers who can regularly afford to buy Greater China high quality imported meat is relatively small in comparison to more developed markets such as the US and Japan. However, (China, Hong Kong and Taiwan) continued strong import demand for premium red meat will be driven by a significant increase in the number of wealthy households. Focusing on targeted opportunities with a differentiated product will help to build preference in what is a large, complex and competitive market. Taiwan and Hong Kong are smaller by comparison but still important markets for Australian red meat, underpinned by a high proportion of affluent households. China meat consumption 1 2 Population Household number by disposable income per capita3 US$35,000+ US$75,000+ 1,444 13% million 94.3 23% 8% 50 kg 56% 44.8 China grocery spend4 10.6 24.2 3.3 5.9 million million 333 26 3.0 51 16.1 Australia A$ Australia Korea China Korea Australia China US US China US Korea 1,573 per person 1,455 million by 2024 5% of total households 0.7% of total households (+1% from 2021) (9% by 2024) (1% by 2024) Australian beef exports to China have grown rapidly, increasing 70-fold over the past 10 years, with the country becoming Australia’s largest market in 2019. Australian beef Australian beef Australia’s share of Australian beef/veal exports – volume5 exports – value6 direct beef imports7 offal cuts exports8 4% 3% 6% 6% 3% Tripe 21% 16% Chilled grass Heart 9% A$ Chilled grain Chilled Australia Tendon Other Frozen grass Frozen 10% 65 71% Tail 17% countries million Frozen grain 84% Kidney 67% Other Total 303,283 tonnes swt Total A$2.83 billion Total 29,687 tonnes swt China has rapidly become Australia’s single largest export destination for both lamb and mutton. -

Reinforcing the U.S.-Taiwan Relationship

Reinforcing the U.S.-Taiwan Relationship Testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific United States House of Representatives Mark Stokes Executive Director The Project 2049 Institute Tuesday, April 17, 2018 Mr. Chairman and esteemed subcommittee members, thank you for the opportunity to testify today alongside my two distinguished colleagues. My remarks address the United States and future policy options in the Taiwan Strait. With the inauguration of President Tsai Ing-wen and the administration of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in May 2016, the Republic of China (Taiwan) completed its third peaceful transition of presidential power and the first transfer of power within its legislature in history. Since that time, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and its ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have sought to further isolate Taiwan internationally and coerce its democratically-elected government militarily. Panama and Sao Tome and Príncipe's abrupt shifts in diplomatic relations from the ROC to PRC are recent examples. Authorities in Beijing also have leveraged their financial influence to shut Taiwan out of international organizations, such as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), and the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), among others. Tourists holding ROC passports are denied entry into the United Nations. The Chinese Communist Party has long sought the political subordination of people on Taiwan under its formula for unification -- “One Country, Two Systems.” Under this so- called “One China Principle,” there is One China, Taiwan is part of China, and the PRC is the sole representative of China in the international community. -

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

Communists Take Power in China

2 Communists Take Power in China MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES REVOLUTION After World War II, China remains a Communist •Mao Zedong • Red Guards Chinese Communists defeated country and a major power in • Jiang Jieshi • Cultural Revolution Nationalist forces and two the world. • commune separate Chinas emerged. SETTING THE STAGE In World War II, China fought on the side of the victo- rious Allies. But the victory proved to be a hollow one for China. During the war, Japan’s armies had occupied and devastated most of China’s cities. China’s civilian death toll alone was estimated between 10 to 22 million persons. This vast country suffered casualties second only to those of the Soviet Union. However, conflict did not end with the defeat of the Japanese. In 1945, opposing Chinese armies faced one another. TAKING NOTES Communists vs. Nationalists Recognizing Effects Use a chart to identify As you read in Chapter 14, a bitter civil war was raging between the Nationalists the causes and effects and the Communists when the Japanese invaded China in 1937. During World of the Communist War II, the political opponents temporarily united to fight the Japanese. But they Revolution in China. continued to jockey for position within China. Cause Effect World War II in China Under their leader, Mao Zedong (MOW dzuh•dahng), 1. 1. the Communists had a stronghold in northwestern China. From there, they mobi- 2. 2. lized peasants for guerrilla war against the Japanese in the northeast. Thanks to 3. 3. their efforts to promote literacy and improve food production, the Communists won the peasants’ loyalty. -

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

Shaken, Not Stirred: Markus Wolfâ•Žs Involvement in the Guillaume Affair

Voces Novae Volume 4 Article 6 2018 Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf’s Involvement in the Guillaume Affair and the Evolution of Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR Jason Hiller Chapman University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Recommended Citation Hiller, Jason (2018) "Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf’s Involvement in the Guillaume Affair nda the Evolution of Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR," Voces Novae: Vol. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol4/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hiller: Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf’s Involvement in the Guillaume A Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, Vol 3, No 1 (2012) HOME ABOUT USER HOME SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES PHI ALPHA THETA Home > Vol 3, No 1 (2012) > Hiller Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf's Involvement in the Guillaume Affair and the Evolution of Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR Jason Hiller "The principal link in the chain of revolution is the German link, and the success of the world revolution depends more on Germany than upon any other country." -V.I. Lenin, Report of October 22, 1918 The game of espionage has existed longer than most people care to think. However, it is not important how long ago it started or who invented it. What is important is the progress of espionage in the past decades and the impact it has had on powerful nations. -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

The One China Policy and Taiwan: Trump Is Playing with Fire Next to A

January 2017 1/2017 Jyrki Kallio The Finnish Institute of International Affairs The One China policy and Taiwan:Trump is playing with fire next to a powder keg Will the Taiwan Issue once again become central to US-China relations once Donald Trump’s presidential term gets underway or is it just a storm in a teacup? US President-elect Donald Trump still officially considered a province, recognizes the government of the indicated in a TV news interview in although its factual independence is PRC as the sole legal government of December 2016: “I don’t know why tolerated in practice. Internationally, China. At the same time, according we have to be bound by a One China Taiwan can be considered a sovereign to the EEAS factsheet on EU-Taiwan policy unless we make a deal with nation in many aspects – the most relations, it insists that any arrange- China having to do with other things, significant exception being the lack ment between the two sides of the including trade”. The sentiment of recognition by the majority of the Taiwan Strait can only be achieved that China is playing by unfair rules world’s countries and international on a mutually acceptable basis, is widely shared in the US, but the organizations like the UN. “with reference also to the wishes suggestion of using the One China The One China policy is central of the Taiwanese population”. This policy as a bargaining chip was new. to the PRC’s diplomatic relations. means that the EU, similarly to the To make matters worse for China, It means that any country that US, does not unconditionally accept the Taiwanese leader, Tsai Ing-wen, recognizes the PRC must break the PRC’s claim over Taiwan. -

Explaining Irredentism: the Case of Hungary and Its Transborder Minorities in Romania and Slovakia

Explaining irredentism: the case of Hungary and its transborder minorities in Romania and Slovakia by Julianna Christa Elisabeth Fuzesi A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Government London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2006 1 UMI Number: U615886 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615886 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. Signature Date ....... 2 UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Abstract of Thesis Author (full names) ..Julianna Christa Elisabeth Fiizesi...................................................................... Title of thesis ..Explaining irredentism: the case of Hungary and its transborder minorities in Romania and Slovakia............................................................................................................................. ....................................................................................... Degree..PhD in Government............... This thesis seeks to explain irredentism by identifying the set of variables that determine its occurrence. To do so it provides the necessary definition and comparative analytical framework, both lacking so far, and thus establishes irredentism as a field of study in its own right. The thesis develops a multi-variate explanatory model that is generalisable yet succinct. -

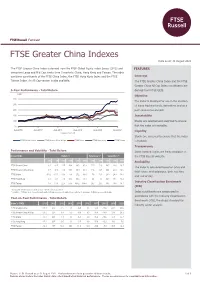

FTSE Greater China Indexes

FTSE Russell Factsheet FTSE Greater China Indexes Data as at: 31 August 2021 bmkTitle1 The FTSE Greater China Index is derived from the FTSE Global Equity Index Series (GEIS) and FEATURES comprises Large and Mid Cap stocks from 3 markets: China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The index combines constituents of the FTSE China Index, the FTSE Hong Kong Index and the FTSE Coverage Taiwan Index. An All Cap version is also available. The FTSE Greater China Index and the FTSE Greater China All Cap Index constituents are 5-Year Performance - Total Return derived from FTSE GEIS. (HKD) Objective 300 The index is designed for use in the creation 250 of index tracking funds, derivatives and as a 200 performance benchmark. 150 Investability 100 Stocks are selected and weighted to ensure 50 that the index is investable. Aug-2016 Aug-2017 Aug-2018 Aug-2019 Aug-2020 Aug-2021 Liquidity Data as at month end Stocks are screened to ensure that the index FTSE Greater China FTSE Greater China All Cap FTSE China FTSE Hong Kong FTSE Taiwan is tradable. Transparency Performance and Volatility - Total Return Index methodologies are freely available on Index (HKD) Return % Return pa %* Volatility %** the FTSE Russell website. 3M 6M YTD 12M 3YR 5YR 3YR 5YR 1YR 3YR 5YR Availability FTSE Greater China -8.1 -8.7 -1.7 10.4 38.5 81.0 11.5 12.6 18.5 20.6 16.7 The index is calculated based on price and FTSE Greater China All Cap -7.5 -7.6 -0.6 11.5 38.9 80.3 11.6 12.5 18.1 20.4 16.6 total return methodologies, both real time FTSE China -13.2 -17.0 -11.6 -3.9 25.2 63.4 7.8 10.3 23.3 24.0 19.0 and end of day. -

Schießbefehl and the Issues of Retroactivity Within the East German Border Guard Trials Keegan Mcmurry Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2018 Schießbefehl and the Issues of Retroactivity Within the East German Border Guard Trials Keegan McMurry Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, Legal Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation McMurry, Keegan, "Schießbefehl and the Issues of Retroactivity Within the East German Border Guard Trials" (2018). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 264. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/264 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schießbefehl1 and the Issues of Retroactivity Within the East German Border Guard Trials Keegan J. McMurry History 499: Senior Seminar June 5, 2018 1 On February 5th, 1989, 20-year old Chris Gueffroy and his companion, Christian Gaudin, were running for their lives. Tired of the poor conditions in the German Democratic Republic and hoping to find better in West Germany, they intended to climb the Berlin Wall that separated East and West Berlin using a ladder. A newspaper account states that despite both verbal warnings and warning shots, both young men continued to try and climb the wall until the border guards opened fire directly at them. Mr. Gaudin survived the experience after being shot, however, Mr.