Organized Animal Protection in the United

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPANION Disorientation and Depression

INSIDE Love at First A “Kneady” Cat Nevins Farm Pet Horoscopes! Sight Gets the Care Winter Page 7 Page 2 She Needs Festival —Come Page 3 Meet Santa! Page 4 Holiday Poison Control Animal Poison Control Hotline 877-2ANGELL Along with holiday and winter fun come a exaggerated, mild stomach upset could still host of hazards for pets — ingested occur if ingested. substances that can be harmful or 5. Yeast dough: If swallowed, even cause death. To help pet uncooked yeast dough can rise in caretakers deal with these the stomach and cause extreme emergencies, the Angell Animal discomfort. Pets who have eaten Medical Centers have teamed up bread dough may experience with the ASPCA’s board-certified abdominal pain, bloat, vomiting, veterinary toxicologists to offer a COMPANION disorientation and depression. unique 24-hour, seven-days-a-week Since a breakdown product of poison hotline. Help is now just a rising dough is alcohol, it can Fall/Winter 2005 phone call away. Call the also potentially cause alcohol Angell Animal Poison Control Chocolate causes indigestion. poisoning. Many yeast Hotline at 877-2ANGELL. Here ingestions require surgical removal of is a list of 10 items that you should keep the dough, and even small amounts can away from your pets this holiday season: be dangerous. 1. Chocolate: Clinical effects can 6. Table food (fatty, spicy), moldy be seen with the ingestion of Sam was in desperate need of blood due to foods, poultry bones: Poultry as little as 1/4 ounce of the severity of her condition. Luckily, Angell bones can splinter and cause baking chocolate by a is able to perform blood transfusions on-site. -

Rev. Kim K. Crawford Harvie Arlington Street Church 3 October, 2010

1 Rev. Kim K. Crawford Harvie Arlington Street Church 3 October, 2010 Love Dogs One night a man was crying, Allah! Allah! His lips grew sweet with the praising, until a cynic said, “So! I have heard you calling out, but have you ever gotten any response?” The man had no answer to that. He quit praying and fell into a confused sleep. He dreamed he saw Khidr,1 the guide of souls, in a thick, green foliage. “Why did you stop praising?” [he asked] “Because I've never heard anything back.” [Khidr, the guide of souls, spoke:] This longing you express is the return message. The grief you cry out from draws you toward union. Your pure sadness that wants help is the secret cup. Listen to the moan of a dog for its master. That whining is the connection. There are love dogs 1 possibly pronounced KY-derr 2 no one knows the names of. Give your life to be one of them.2 That's our friend Rumi, the13th century Persian Sufi mystic: Give your life to be a love dog. George Thorndike Angell was born in 1823. Perhaps because of a childhood in poverty, he had deep convictions about social change. He was already well known for his fourteen year partnership with the antislavery activist Samuel E. Sewall when, one day in March of 1868, two horses, each carrying two riders over forty miles of rough road, were raced until they both dropped dead. George Angell was appalled. He penned a letter of protest that appeared in the Boston Daily Advertiser, “where it caught the attention of Emily Appleton, a prominent Bostonian who deeply loved animals and was already nurturing the first stirrings of an American anticruelty movement. -

A Study of Problematisations in the Live Export Policy Debates

ANIMAL CRUELTY, DISCOURSE, AND POWER: A STUDY OF PROBLEMATISATIONS IN THE LIVE EXPORT POLICY DEBATES Brodie Lee Evans Bachelor of Arts (Politics, Economy, and Society; Literary Studies) Bachelor of Justice (First Class Honours) Graduate Certificate in Business (Accounting) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Queensland University of Technology 2018 School of Justice | Faculty of Law This page intentionally left blank Statement of Originality Under the Copyright Act 1968, this thesis must be used only under the normal conditions of scholarly fair dealing. In particular, no results or conclusions should be extracted from it, nor should it be copied or closely paraphrased in whole or in part without the written consent of the author. Proper written acknowledgement should be made for any assistance obtained from this thesis. The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made. Brodie Evans QUT Verified Signature ……………………………………………………………………….. Signature October 2018 ……………………………………………………………………….. Date i Dedication For Scottie. ii Abstract Since the release of video footage exposing the treatment of animals in the live export industry in 2011, ‘animal cruelty’ has increasingly been a major concern in mainstream Australian discourse. Critiques over the inadequacy of current legal protections afforded to animals have had a significant impact on how we debate animal welfare issues and the solutions to them. -

Animal Abuse As a Sentinel for Human Violence: a Critique ∗ Emily G

Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 65, No. 3, 2009, pp. 589--614 Animal Abuse as a Sentinel for Human Violence: A Critique ∗ Emily G. Patterson-Kane American Veterinary Medical Association Heather Piper Manchester Metropolitan University It has been suggested that acts of violence against human and nonhuman an- imals share commonalities, and that animal abuse is a sentinel for current or future violence toward people. The popular and professional acceptance of strong connections between types of violence is beginning to be used to justify social work interventions and to influence legal decision making, and so requires greater scrutiny. Examination of the limited pool of empirical data suggests that animal abuse is relatively common among men, with violent offenders having an increased probability of reporting prior animal abuse—with the majority of violent offend- ers not reporting any animal abuse. Causal explanations for “the link,” such as empathy impairment or conduct disorder, suffer from a lack of validating research and, based on research into interhuman violence, the assumption that violence has a predominant, single underlying cause must be questioned. An (over)emphasis on the danger that animal abusers pose to humans serves to assist in achieving a consensus that animal abuse is a serious issue, but potentially at the cost of failing to focus on the most common types of abuse, and the most effective strategies for reducing its occurrence. Nothing in this review and discussion should be taken as minimizing the importance of animals as frequent victims of violence, or the co-occurrence of abuse types in “at-risk” households. -

Exploring Human – Animal Interactions a Multidisciplinary Approach from Behavioral and Social Sciences

Proceedings Exploring Human – Animal Interactions a multidisciplinary approach from behavioral and social sciences Barcelona 7th – 10th of July 2016 INTRODUCTION Vision, Goals and Objectives Animals were domesticated thousands of years ago and are now present in almost every human society around the world. Nevertheless, only recently scientists have begun to analyse both positive and negative aspects of human-animal relationships. For centuries people have recognised the value of animals for obvious economical reasons, but also as an important source of physical and emotional wellbeing. Indeed, people’s attitudes towards animals depend on a variety of factors, including socio-economical relationships with each particular species, cultural background, religious believes, as well as individual differences regarding behaviour and personality. A proper understanding of these differences requires a multidisciplinary approach, from psychology, social psychology and anthropology to psychiatry and neuroscience. The main goal of the conference would be to provide delegates with an updated and multi-disciplinary overview of human-animal interactions. Selected topics would include but are not limited to: • The concept of empathy in the study of human-animals interactions. • The concept of protected values (or sacred values) in human-animal interactions. • Understanding cultural views on animals. We will also organise a Satellite Meeting (10th of July) on the state of the art of the abandonment of companion animals and global strategies to prevent the abandonment. ISAZ grateFULLY acKnoWLedges the generous support OF the 2016 conFerence FroM the FOLLOWing sponsors and COLLaborators Sponsors Collaborators 2 PROGRAM Thursday 7th July Friday 8th July 19:00 – 20:30 8:00 – 18:30 Welcome Ceremony Registration at the PRBB Barcelona City Council 9:00 – 9:15 Opening address 9:15 – 10:15 Keynote Speaker Dr. -

Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe's Stories

Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories A Tale of a Ragged Mountain, The Black Cat,Ttale - Tell Heart THESIS Nurin Aliyafi Romadhoni (10320105) ENGLISH LETTERS AND LANGUAGE DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITY THE STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2014 i Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories A Tale of a Ragged Mountain, The Black Cat,Tale - Tell Heart THESIS Presented to: State Islamic University Maulana Malik Ibrahim of Malang in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra (S1) in English Letters and Language Department Nurin Aliyafi Romadhoni (10320105) Supervisor : Ahmad Ghozi, M.A. ENGLISH LETTERS AND LANGUAGE DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITY THE STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2014 ii APPROVAL SHEET This is to certify that Nurin Aliyafi Romadhoni’s thesis entitled Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories has been approved by the thesis advisor For further approval by the Board of Examiners. Malang, 5 june 2014 Approved by Acknowledged by The Advisor, The Head of the Department of English Language and Literature, Ahmad Ghozi, M. A. Dr. Syamsuddin, M.Hum NIP. 1976911222006041001 Approved by The Dean of Faculty of Humanities Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University Malang Dr. Hj. Istiadah, M.A NIP. 19670313 1991032 2 001 iii LEGITIMATION SHEET This is to certify that Nurin Aliyafi Romadhoni’s thesis entitled Animal Symbols in Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories has been approved by the Board of Examiners as the requirement for the degree of Sarjana Sastra The Board of Examiners Signatures Andarwati, M. A. (Main Examiner) ___________ NIP. -

Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ANIMAL WELFARE Marc Bekoff Editor Greenwood Press Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ANIMAL WELFARE Edited by Marc Bekoff with Carron A. Meaney Foreword by Jane Goodall Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of animal rights and animal welfare / edited by Marc Bekoff with Carron A. Meaney ; foreword by Jane Goodall. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–29977–3 (alk. paper) 1. Animal rights—Encyclopedias. 2. Animal welfare— Encyclopedias. I. Bekoff, Marc. II. Meaney, Carron A., 1950– . HV4708.E53 1998 179'.3—dc21 97–35098 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 1998 by Marc Bekoff and Carron A. Meaney All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97–35098 ISBN: 0–313–29977–3 First published in 1998 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Cover Acknowledgments: Photo of chickens courtesy of Joy Mench. Photo of Macaca experimentalis courtesy of Viktor Reinhardt. Photo of Lyndon B. Johnson courtesy of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library Archives. Contents Foreword by Jane Goodall vii Preface xi Introduction xiii Chronology xvii The Encyclopedia 1 Appendix: Resources on Animal Welfare and Humane Education 383 Sources 407 Index 415 About the Editors and Contributors 437 Foreword It is an honor for me to contribute a foreword to this unique, informative, and exciting volume. -

MSPCA-AR2-14-Final.Pdf

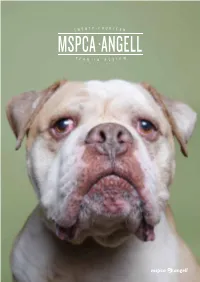

MSPCA ANGELL THE MISSION OF THE MASSACHUSETTS SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALS AND THE ANGELL ANIMAL MEDICAL CENTER IS TO PROTECT ANIMALS, RELIEVE THEIR SUFFERING, ADVANCE THEIR HEALTH ONE OF THE THINGS I LOVE ABOUT THIS PLACE AND WELFARE, PREVENT CRUELTY, AND WORK “PREVENTION IS BETTER THAN CURE” FOR A JUST AND COMPASSIONATE SOCIETY. Desiderius Erasmus, classical scholar, 16th century Around the MSPCA–Angell, we don’t even think about it; I think we do all that here; it’s one of the things I love about we just breathe it in and out. Prevention, that is. this place. Prevention involves thinking, planning, and taking action. Pet overpopulation? We figure out the best ways We consider it to be our middle name: the Massachusetts to address it, and we take the necessary steps. Innovations Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. And when in veterinary medicine? Our medical team is always in the you think about it, our name is pretty brilliant — because every forefront. Laws to ban cruel practices? Our Advocacy staff time we manage to prevent cruelty, we’re changing the world in works hard to make them a reality. All throughout our no small way. organization, we are using our heads and our hearts for the I’m sure you can easily imagine how each of our programs betterment of animals and people everywhere. Letter from the President Law Enforcement Events Financial weaves prevention into its fabric — and some examples of how I know that all of you — the wonderful people who are so 1 Angell Animal 7 12 18 they do that will be illustrated in the pages of this Review — generous to us — appreciate the importance of our investment Medical Center Advocacy Donor Overview but what amazes me is the magnitude and complexity of the in prevention. -

THE VIVISECTION CONTROVERSY in AMERICA CLAUDIA ALONSO RECARTE Friends of Thoreau Environmental Program Franklin Institute, University of Alcalá

THE VIVISECTION CONTROVERSY IN AMERICA CLAUDIA ALONSO RECARTE Friends of Thoreau Environmental Program Franklin Institute, University of Alcalá Guiding Students’ Discussion Scholars Debate Works Cited Links to Online Sources Acknowledgements & Illustration Credits MAIN PAGE Rabbit being used for experimental purposes. Courtesy of the New England Anti-Vivisection Society (NEAVS). MAIN PAGE 1. Introduction and Note on the Text Vivisection and animal experimentation constitute one of the institutionalized pillars of animal exploitation, and they bear a long history of political, ethical and social 1 controversies. Vivisection must not be considered as solely the moment in which an animal’s body is cut into; as will soon become evident, vivisection and animal experimentation include a whole array of procedures that are not limited to the act of severing (see Item 2 of the MAIN PAGE, hereinafter referred to as the MP), and should as well include as part of their signification the previous and subsequent conditions to the procedures in which the animals are in. It is quite difficult to ascertain the number of nonhuman others that are annually used in the United States for scientific and educational purposes, mainly due to the neglect in recording information regarding invertebrate specimens. According to the Last Chance for Animals website, the US Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service reported that in the year 2009 1.13 million animals were used in experiments. These numbers did not include rats, mice, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and agricultural animals used for agricultural experiments. To this, an estimate of 100 million rats and mice were added. -

Self-Guided Tour Packet Packet Contents: Boston

Self-Guided Tour Packet This packet is designed to provide individuals, families, and small groups information about our Adoption Centers and the animals we place for adoption. To best utilize this packet, we suggest you start by reviewing the “Safety Guidelines” with your group. Use the enclosed map to find the 5 stations on the property that correspond to the animal information sheets in your packet. The first station is our rabbit adoption room, found to the left of the front door of the Boston Animal Care and Adoption Center. As you visit each animal adoption area, you can learn more about our animals and why they come to the MSPCA by reading the related sheets. We hope you enjoy your visit, and have a safe and fun learning experience! Packet Contents: Safety Guidelines All about the MSPCA 5 Station Sheets with Animal Information Boston Animal Care and Adoption Center a. Rabbits b. Cats c. Dogs d. Small Mammals e. Birds Wish List Safety Guidelines There is a lot of traffic on the property, from cars going up and down the driveway to the adoption center. Be mindful of your surroundings and keep your group together. Animals are constantly moving in and out of the adoption center and the hospital next door. Be cautious and give plenty of room to these animals. Please keep in mind that you are visiting a working animal shelter and not a petting zoo. Animals should not be touched or fed. If you would like to handle an animal, you must ask a staff or volunteer. -

Print Layout

INSIDE A special senior Become an The Abousema family Test your Knowledge — gets the pampered Animal Angel and many like them Crossword Puzzle treatment Page 3 need your help Page 7 Page 2 Page 5 Animals You Have Helped this Year In 2006 alone, donors like you have helped tremendous support of donors like you, us save the lives of thousands of animals. It Olivia has since been treated with antibiotics is only with your help that we are able to and underwent successful eye removal care for these sick, injured, neglected and surgery. She has been adopted and is living abused animals. Lulu, Ralph and Olivia are happily in her new home. three of the animals that have benefited COMPANION To continue to make a difference in the from your donations this year. lives of animals like Lulu, Ralph and Olivia, Fall/Winter 2006 Brought to Angell by firefighters, Lulu, a visit www.mspca.org/companion and make Pug/Chihuahua mix, was burned and injured a donation today. in an apartment fire in Springfield, Massachusetts in August 2006. She was brought to the MSPCA-Angell in Western New England (WNE) where she was treated for a broken femur, smoke inhalation and burns. Following her television debut, Lulu fully recovered from her injuries and was adopted by Cindy and Joshua Serino. Just Ralph, a grey tabby kitten, was the victim of a senseless act of cruelty. A concerned citizen brought Ralph into the MSPCA-Angell after she saw a group of kids swinging him Ralph (top) and Lulu (center) are some Look at of the 250,000 animals that we have cared for this around by his rear leg. -

Cat SURVIVES WATERY Ordeal

FALL/WINTER 2010 MSPCA.ORG 350 South Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02130 Non-profit Org. U.S. Postage PAID MSPCA/Angell The mission of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals–Angell Animal Medical Center is to protect animals, relieve their suffering, advance their health and welfare, prevent cruelty, and work for a just and compassionate society. NEW BARN FOR BIRDS AT NEVINS DONATIONS FEATHER A COMFY NEW NEST ANTIFREEZE BILL WILL SAVE LIVES NO MORE SWEET POISON Please Like Us on Facebook Can You See into the Future? TO TEMPT ANIMALS Do you and your friends enjoy connecting with You don’t need a crystal ball to know that animals will always need our each other on Facebook? If so, please “like” the help. We’ve been helping them, with the support of friends like you, MSPCA–Angell page. MSPCA at Nevins Farm has its since 1868. own Facebook page, too, as do our MSPCA Animal Please, as you make your estate plans, consider a bequest to the Action Team and The American Fondouk. All our MSPCA–Angell as a fitting continuation of your lifelong love for pages are updated frequently and filled with interesting animals. And when you do, please let us know! We’d like to invite you into our Circle of Friends and acknowledge your thoughtful concern for the news about animals and the people who love them. future of our organization. By providing for the animals in your own It’s yet another important way we can get the message future plans, you become an essential member of our Society.